Conservation of Biological Diversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Threatened Species Status Assessment Manual

THREATENED SPECIES SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Established under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 THREATENED SPECIES STATUS ASSESSMENT MANUAL A guide to undertaking status assessments, including the preparation and submission of a status report for threatened species. Knowledge of species and their status improves continuously. Due to the large numbers of both listed and non-listed species, government resources are not generally available to carry out regular and comprehensive assessments of all listed species that are threatened or assess all non-listed species to determine their listing status. A status assessment by a group of experts, with their extensive collection of knowledge of a particular taxon or group of species could help to ensure that advice is the most current and accurate available, and provide for collective expert discussion and decisions regarding any uncertainties. The development of a status report by such groups will therefore assist in maintaining the accuracy of the list of threatened species under the EPBC Act and ensure that protection through listing is afforded to the correct species. 1. What is a status assessment? A status assessment is a assessment of the conservation status of a specific group of taxa (e.g. birds, frogs, snakes) or multiple species in a region (e.g. Sydney Basin heathland flora) that occur within Australia. For each species or subspecies (referred to as a species in this paper) assessed in a status assessment the aim is to: provide an evidence-based assessment -

Natura 2000 and Forests

Technical Report - 2015 - 089 ©Peter Loeffler Natura 2000 and Forests Part III – Case studies Environment Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union New freephone number: 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://ec.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2015 ISBN 978-92-79-49397-3 doi: 10.2779/65827 © European Union, 2015 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Disclaimer This document is for information purposes only. It in no way creates any obligation for the Member States or project developers. The definitive interpretation of Union law is the sole prerogative of the Court of Justice of the EU. Cover Photo: Peter Löffler This document was prepared by François Kremer and Joseph Van der Stegen (DG ENV, Nature Unit) and Maria Gafo Gomez-Zamalloa and Tamas Szedlak (DG AGRI, Environment, forestry and climate change Unit) with the assistance of an ad-hoc working group on Natura 2000 and Forests composed by representatives from national nature conservation and forest authorities, scientific institutes and stakeholder organisations and of the N2K GROUP under contract to the European Commission, in particular Concha Olmeda, Carlos Ibero and David García (Atecma S.L) and Kerstin Sundseth (Ecosystems LTD). Natura 2000 and Forests Part III – Case studies Good practice experiences and examples from different Member States in managing forests in Natura 2000 1. Setting conservation objectives for Natura 2000. -

Buglife Ditches Report Vol1

The ecological status of ditch systems An investigation into the current status of the aquatic invertebrate and plant communities of grazing marsh ditch systems in England and Wales Technical Report Volume 1 Summary of methods and major findings C.M. Drake N.F Stewart M.A. Palmer V.L. Kindemba September 2010 Buglife – The Invertebrate Conservation Trust 1 Little whirlpool ram’s-horn snail ( Anisus vorticulus ) © Roger Key This report should be cited as: Drake, C.M, Stewart, N.F., Palmer, M.A. & Kindemba, V. L. (2010) The ecological status of ditch systems: an investigation into the current status of the aquatic invertebrate and plant communities of grazing marsh ditch systems in England and Wales. Technical Report. Buglife – The Invertebrate Conservation Trust, Peterborough. ISBN: 1-904878-98-8 2 Contents Volume 1 Acknowledgements 5 Executive summary 6 1 Introduction 8 1.1 The national context 8 1.2 Previous relevant studies 8 1.3 The core project 9 1.4 Companion projects 10 2 Overview of methods 12 2.1 Site selection 12 2.2 Survey coverage 14 2.3 Field survey methods 17 2.4 Data storage 17 2.5 Classification and evaluation techniques 19 2.6 Repeat sampling of ditches in Somerset 19 2.7 Investigation of change over time 20 3 Botanical classification of ditches 21 3.1 Methods 21 3.2 Results 22 3.3 Explanatory environmental variables and vegetation characteristics 26 3.4 Comparison with previous ditch vegetation classifications 30 3.5 Affinities with the National Vegetation Classification 32 Botanical classification of ditches: key points -

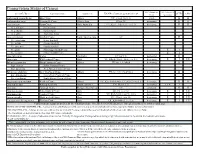

Conservation Status of Cranes

Conservation Status of Cranes IUCN Population ESA Endangered Scientific Name Common name Continent IUCN Red List Category & Criteria* CITES CMS Trend Species Act Anthropoides paradiseus Blue Crane Africa VU A2acde (ver 3.1) stable II II Anthropoides virgo Demoiselle Crane Africa, Asia LC(ver 3.1) increasing II II Grus antigone Sarus Crane Asia, Australia VU A2cde+3cde+4cde (ver 3.1) decreasing II II G. a. antigone Indian Sarus G. a. sharpii Eastern Sarus G. a. gillae Australian Sarus Grus canadensis Sandhill Crane North America, Asia LC II G. c. canadensis Lesser Sandhill G. c. tabida Greater Sandhill G. c. pratensis Florida Sandhill G. c. pulla Mississippi Sandhill Crane E I G. c. nesiotes Cuban Sandhill Crane E I Grus rubicunda Brolga Australia LC (ver 3.1) decreasing II Grus vipio White-naped Crane Asia VU A2bcde+3bcde+4bcde (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Balearica pavonina Black Crowned Crane Africa VU (ver 3.1) A4bcd decreasing II B. p. ceciliae Sudan Crowned Crane B. p. pavonina West African Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum Grey Crowned Crane Africa EN (ver. 3.1) A2acd+4acd decreasing II B. r. gibbericeps East African Crowned Crane B. r. regulorum South African Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled Crane Africa VU A2acde+3cde+4acde; C1+2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing II II Grus americana Whooping Crane North America EN, D (ver 3.1) increasing E, EX I Grus grus Eurasian Crane Europe/Asia/Africa LC unknown II II Grus japonensis Red-crowned Crane Asia EN, C1 (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Grus monacha Hooded Crane Asia VU B2ab(I,ii,iii,iv,v); C1+2a(ii) decreasing E I I,II Grus nigricollis Black-necked Crane Asia VU C2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Leucogeranus leucogeranus Siberian Crane Asia CR A3bcd+4bcd (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Conservation status of species in the wild based on: The 2015 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, www.redlist.org CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) - A taxon is Critically Endangered when it is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future. -

Conservation–Protection of Forests for Wildlife in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley

Article Conservation–Protection of Forests for Wildlife in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley A. Blaine Elliott 1, Anne E. Mini 1, S. Keith McKnight 2 and Daniel J. Twedt 3,* 1 Lower Mississippi Valley Joint Venture, 193 Business Park Drive, Ridgeland, MS 39157, USA; [email protected] (A.B.E.); [email protected] (A.E.M.) 2 Lower Mississippi Valley Joint Venture, 11942 FM 848, Tyler, TX 75707, USA; [email protected] 3 U.S. Geological Survey, Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, 3918 Central Ave., Memphis, TN 38152, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-601-218-1196 Received: 2 December 2019; Accepted: 23 December 2019; Published: 8 January 2020 Abstract: The nearly ubiquitous bottomland hardwood forests that historically dominated the Mississippi Alluvial Valley have been greatly reduced in area. In addition, changes in hydrology and forest management have altered the structure and composition of the remaining forests. To ameliorate the detrimental impact of these changes on silvicolous wildlife, conservation plans have emphasized restoration and reforestation to increase the area of interior (core) forest habitat, while presuming negligible loss of extant forest in this ecoregion. We assessed the conservation–protection status of land within the Mississippi Alluvial Valley because without protection, existing forests are subject to conversion to other uses. We found that only 10% of total land area was currently protected, although 28% of extant forest was in the current conservation estate. For forest patches, we prioritized their need for additional conservation–protection based on benefits to forest bird conservation afforded by forest patch area, geographic location, and hydrologic condition. Based on these criteria, we found that 4712 forest patches warranted conservation–protection, but only 109 of these forest patches met our desired conservation threshold of >2000 ha of core forest that was >250 m from an edge. -

Environmental Requirements for Afforestation

Environmental Requirements for Afforestation December 2016 The Forest Service of the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine is responsible for ensuring the development of forestry within Ireland in a manner and to a scale that maximises its contribution to national socio-economic well-being on a sustainable basis that is compatible with the protection of the environment. Its strategic objectives are: 1. To foster the efficient and sustainable development of forestry 2. To increase quality planting 3. To promote the planting of diverse tree species 4. To improve the level of farmer participation in forestry 5. To promote research and training in the sector 6. To encourage increased employment in the sector Published by: Forest Service Department of Agriculture, Food & the Marine, Johnstown Castle Estate Co. Wexford Tel. 053 91 63400 / Lo-Call 1890 200 509 E-mail [email protected] Web www.agriculture.gov.ie/forestservice All photos Forest Service unless otherwise stated. Illustrations by Aislinn Adams © Forest Service, Department of Agriculture, Food & the Marine, Ireland December 2016 C Contents Section 1: Introduction 1.1 Context 1 1.2 About these Environmental Requirements 2 Section 2: Design 2.1 Overview 3 2.2 Background checks 3 2.3 Basic requirements at design stage 3 2.4 Water 4 2.5 Biodiversity 8 2.6 Archaeology and built heritage 16 2.7 Landscape 20 2.8 Environmental setbacks 24 2.9 Future operational areas 28 2.10 Open spaces and deer management 28 2.11 Site inputs 29 2.12 Further environmental assessment -

Rehabilitation and Restoration of Degraded Forests

Issues in Forest Conservation IUCN – The World Conservation Union Rehabilitation and Restoration of Degraded Forests Founded in 1948, The World Conservation Union brings together States, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations in a unique world partnership: nearly 980 members in all, spread across some 140 countries. Rehabilitation As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically and Restoration sustainable. A central secretariat coordinates the IUCN Programme and serves the Union membership, representing their views on the world stage and providing them with the strategies, services, scientific knowledge and of Degraded Forests technical support they need to achieve their goals. Through its six Commis- sions, IUCN draws together over 10,000 expert volunteers in project teams and action groups, focusing in particular on species and biodiversity conser- vation and the management of habitats and natural resources. The Union has helped many countries to prepare National Conservation Strategies, and David Lamb and Don Gilmour demonstrates the application of its knowledge through the field projects it supervises. Operations are increasingly decentralized and are carried forward by an expanding network of regional and country offices, located principally in developing countries. The World Conservation Union builds on the strengths of its members, -

A Conservation Assessment of the Terrestrial Ecoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean

A Conservation Assessment Public Disclosure Authorized of the Terrestrial Ecoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Eric Dinerstein David M. Olson Douglas ). Graham Avis L. Webster Steven A. Primm Marnie P. Bookbinder George Ledec Public Disclosure Authorized r Published in association with The World Wildlife Fund The World Bank WWF Washington, D.C. A ConservationAssessment of the TerrestrialEcoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean A Conservation Assessment of the Terrestrial Ecoregions of Latin America and the Caribbean Eric Dinerstein David M. Olson Douglas J. Graham Avis L. Webster Steven A. Primm Marnie P. Bookbinder George Ledec Published in association with The World Wildlife Fund The World Bank Washington, D.C. © 1995 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First printing September 1995 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this study are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its affiliated organiza- tions, or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility whatsoever for any consequence of their use. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this volume do not imply on the part of the World Bank any judgment on the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. -

The Conservation Status of North American, Central American, and Caribbean Chondrichthyans the Conservation Status Of

The Conservation Status of North American, Central American, and Caribbean Chondrichthyans The Conservation Status of Edited by The Conservation Status of North American, Central and Caribbean Chondrichthyans North American, Central American, Peter M. Kyne, John K. Carlson, David A. Ebert, Sonja V. Fordham, Joseph J. Bizzarro, Rachel T. Graham, David W. Kulka, Emily E. Tewes, Lucy R. Harrison and Nicholas K. Dulvy L.R. Harrison and N.K. Dulvy E.E. Tewes, Kulka, D.W. Graham, R.T. Bizzarro, J.J. Fordham, Ebert, S.V. Carlson, D.A. J.K. Kyne, P.M. Edited by and Caribbean Chondrichthyans Executive Summary This report from the IUCN Shark Specialist Group includes the first compilation of conservation status assessments for the 282 chondrichthyan species (sharks, rays, and chimaeras) recorded from North American, Central American, and Caribbean waters. The status and needs of those species assessed against the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species criteria as threatened (Critically Endangered, Endangered, and Vulnerable) are highlighted. An overview of regional issues and a discussion of current and future management measures are also presented. A primary aim of the report is to inform the development of chondrichthyan research, conservation, and management priorities for the North American, Central American, and Caribbean region. Results show that 13.5% of chondrichthyans occurring in the region qualify for one of the three threatened categories. These species face an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild (Critically Endangered; 1.4%), a very high risk of extinction in the wild (Endangered; 1.8%), or a high risk of extinction in the wild (Vulnerable; 10.3%). -

Annual Report

[Type here] Darwin Initiative Main Project Annual Report Important note: To be completed with reference to the Reporting Guidance Notes for Project Leaders: it is expected that this report will be about 10 pages in length, excluding annexes Submission Deadline: 30 April Darwin Project Information Project Reference 19-029 Project Title Bugs on the brink- Laying the foundations for invertebrate conservation on St Helena Host Country/ies UK and St Helena Contract Holder Institution Buglife- The Invertebrate Conservation Trust Partner institutions St Helena National Trust, St Helena Government, Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (Edinburgh) Darwin Grant Value £199,478 Start/end dates of project 1 April 2012 – 31 January 2016 Reporting period (eg Apr 2013 – Mar 2014) and number April 2014- March 2015, annual report 3 Project Leader name Alice Farr Project website http://www.nationaltrust.org.sh/shnt-conservation- programmes/natural-heritage/bugs-on-the-brink-our- invertebrates/ www.buglife.org.uk/bugs-brink Report author(s) and date Alice Farr with input from David Pryce, Liza Fowler and Alan Gray. April 2015. Project Rationale The project aims to halt declines in endemic invertebrates and integrate their needs within practical and strategic conservation efforts on St Helena and improve capacity to conserve invertebrates in the long term, by providing resources and training. St Helena is a UK Overseas Territory, situated at 15°S and 5°W in the South Atlantic Ocean, between Africa and South America, and this project was designed to encompass the invertebrate conservation on the whole island. The endemic biodiversity of St Helena is severely threatened by the combined effects of habitat degradation and invasive alien species. -

Belize's Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity

Belize’s Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity Reporting Period: 2009 - 2013 September, 2014 Belize’s Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity, submitted by the Forest Department, Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries and Sustainable Development, Belize We thank all those participants who took part in the review process, both in Government agencies, in regional workshops and focal group meetings across Belize. Nature ----- Culture ------ Life This report was produced under the “National Biodiversity Planning to Support the implementation of the CDB 2011 - 2020 Strategic Plan in Belize (National Biodiversity Enabling Activities)” With funding from the United Nations Development Programme – Global Environment Facility Please cite as: Fifth National Report to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity: Belize (2014). Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries and Sustainable Development, Belmopan. INTRODUCTION 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PART 1. UPDATE ON BIODIVERSITY STATUS, TRENDS AND THREATS, AND IMPLICATIONS FOR HUMAN WELLBEING 4 1. The National Importance of Biodiversity to Belize 4 2. Major changes in the status and trends of biodiversity in Belize 14 3. The Main Threats to Biodiversity in Belize 28 4. Impacts of the changes in biodiversity for ecosystem services, and the socioeconomic and cultural implications of these impacts 44 PART II: THE NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGIES AND ACTION PLANS, ITS IMPLEMENTATION AND THE MAINSTREAMING OF BIODIVERSITY 47 5. Belize’s Biodiversity Targets 47 6. Status of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, incorporation of biodiversity targets and mainstreaming of biodiversity. 48 7. Actions Belize has taken to implement the Convention since the fourth report, and the outcomes of these actions. -

The Planning Inspectorate National Infrastructure Planning Temple Quay House 2 the Squae Bristol BS1 6PN

Bug House Ham Lane Orton Waterville Peterborough PE2 5UU Telephone: 01733 201210 E-mail: [email protected] The Planning Inspectorate National Infrastructure Planning Temple Quay House 2 The Squae Bristol BS1 6PN 30th April 2018 Dear Sir/Madam RE: Application by Port of Tilbury London Limited for an Order Granting Development Consent for a Proposed Port Terminal at the Former Tilbury Power Station (‘Tilbury2’) Buglife maintains its previous positions outlined in the comments dated 16th March 2018, but would like to submit further comments to clarify its position in response to the Tilbury 2 Document Ref PoTLL/T2/EX/60 document, titled ‘Response to the written representations, local impact reports and interested parties’ responses to first written questions’. The comments below specifically relate to Port of Tilbury London Ltd (PoTLL) responses in the document highlighted above, with comments grouped by the ‘Source Reference’ listed in section 1.2. Biodiversity and 1.11 Habitats Regulation Assessment for ease of reference: Source Reference: Summary (pg. 31) Buglife maintain the position that the ES fails to accurately assess the extent of the Open mosaic habitat on previously developed land (OMHPDL), a habitat of conservation priority listed under Section 41 of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities (NERC) Act 2006. OMHPDL is widely acknowledged as a diverse and difficult to define habitat, as reflected in the Priority Habitat criteria and addressed later in this document. Source Reference: The presence of an outstanding invertebrate assemblage of SSSI quality (pg. 31) & Loss of Local Wildlife Sites and potential SSSI habitat (pg.32) PoTLL has requested evidence to support Buglife’s suggestion that the site “one of the most important in the Thames Estuary area” or “one of the most valuable sites yet surveyed”, stating that, “No statistical comparison with other Thames Estuary brownfields is offered.” The 2016 and 2017 surveys undertaken by Colin Plant Associates and Mark Telfer jointly recorded 1,397 species.