LANGUAGE and LEARNING a Discourse Analytical Study of the Children TV Programme Team Umizoomi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

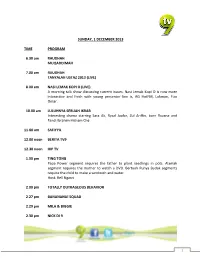

1 SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 Am

SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 am RAUDHAH MUQADDIMAH 7.00 am RAUDHAH TANYALAH USTAZ 2013 (LIVE) 8.00 am NASI LEMAK KOPI O (LIVE) A morning talk show discussing current issues. Nasi Lemak Kopi O is now more interactive and fresh with young presenter line is, AG HotFM, Lokman, Fizo Omar. 10.00 am LULUHNYA SEBUAH IKRAR Interesting drama starring Sara Ali, Ryzal Jaafar, Zul Ariffin, born Ruzana and Fandi Ibrahim Hisham Che 11.00 am SAFIYYA 12.00 noon BERITA TV9 12.30 noon HIP TV 1.00 pm TING TONG Papa Power segment requires the father to plant seedlings in pots. Alamak segment requires the mother to watch a DVD. Bertuah Punya Budak segments require the child to make a sandwich and water. Host: Bell Ngasri 2.00 pm TOTALLY OUTRAGEOUS BEHAVIOR 2.27 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 2.29 pm MILA & BIGGIE 2.30 pm NICK DI 9 1 TEAM UMIZOOMI 3.00 pm NICK DI 9 DORA THE EXPLORER 3.30 pm NICK DI 9 ADVENTURES OF JIMMY NEUTRONS 4.00 pm NICK DI 9 PLANET SHEEN 4.30 pm NICK DI 9 AVATAR THE LEGEND OF AANG 5.00 pm NICK DI 9 SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS 5.28 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 5.30 pm BOLA KAMPUNG THE MOVIE Amanda is a princess who comes from the virtual world of a game called "Kingdom Hill '. She was sent to the village to find Pewira Suria, the savior who can end the current crisis. Cast: Harris Alif, Aizat Amdan, Harun Salim Bachik, Steve Bone, Ezlynn 7.30 pm SWITCH OFF 2 The Award Winning game show returns with a new twist! Hosted by Rockstar, Radhi OAG, and the game challenges bands with a mission to save their band members from the Mysterious House in the Woods. -

Nickelodeon Previews New Content Pipeline for 2014-2015 Season at Annual Upfront Presentation

Nickelodeon Previews New Content Pipeline for 2014-2015 Season at Annual Upfront Presentation Nick to Add 10 New Series to Schedule, with Content Spanning Every Genre, Every Platform Network Unveils Plans for Brand-New, Live Tent-Pole Event, Kids' Choice Sports 2014; Host/Executive Producer Michael Strahan Details Show Slated for 3Q 2014 Upfront Presentation Capped by Special Musical Performance from Five-Time Grammy Nominee Sara Bareilles NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Nickelodeon held its annual upfront presentation today at Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City, where Nickelodeon Group President Cyma Zarghami detailed the network's biggest content pipeline ever: 10 new series across every genre, and for every platform—all tailor-made for the tastes of today's post-millennial generation of kids. Zarghami also announced plans for the forthcoming Nick Jr. App, featuring TV Everywhere capability, and the brand-new, live tent-pole event, Kids' Choice Sports—the first-ever expansion of the highly successful Kids' Choice Awards franchise. Nickelodeon's presentation was also punctuated by remarks from Viacom Chairman Philippe Dauman; an appearance by Kids' Choice Sports 2014 host and executive producer Michael Strahan; and a closing musical performance from five-time Grammy nominee Sara Bareilles. "Our mission has been to create and deliver funny content that will resonate with today's kids, and we are well-positioned to do that through our schedule of fresh hits, a deep pipeline of new series, tent-pole events, ratings momentum and innovation on all platforms," said Zarghami. "Nickelodeon is a magnet for creative people and projects, and we're incredibly excited about the new pool of talent we're bringing to our audience in front of and behind the camera." Nickelodeon has posted 13 straight months of year-over-year growth and reclaimed the top spot with kids in 4Q13. -

Brand Armani Jeans Celebry Tees Rochas Roberto Cavalli Capcho

Brand Armani Jeans Celebry Tees Rochas Roberto Cavalli Capcho Lady Million Just Over The Top Tommy Hilfiger puma TJ Maxx YEEZY Marc Jacobs British Knights ROSALIND BREITLING Polo Vicuna Morabito Loewe Alexander Wang Kenzo Redskins Little Marcel PIGUET Emu Affliction Bensimon valege Chanel Chance Swarovski RG512 ESET Omega palace Serge Pariente Alpinestars Bally Sven new balance Dolce & Gabbana Canada Goose thrasher Supreme Paco Rabanne Lacoste Remeehair Old Navy Gucci Fjallraven Zara Fendi allure bridals BLEU DE CHANEL LensCrafters Bill Blass new era Breguet Invictus 1 million Trussardi Le Coq Sportif Balenciaga CIBA VISION Kappa Alberta Ferretti miu miu Bottega Veneta 7 For All Mankind VERNEE Briston Olympea Adidas Scotch & Soda Cartier Emporio Armani Balmain Ralph Lauren Edwin Wallace H&M Kiss & Walk deus Chaumet NAKED (by URBAN DECAY) Benetton Aape paccbet Pantofola d'Oro Christian Louboutin vans Bon Bebe Ben Sherman Asfvlt Amaya Arzuaga bulgari Elecoom Rolex ASICS POLO VIDENG Zenith Babyliss Chanel Gabrielle Brian Atwood mcm Chloe Helvetica Mountain Pioneers Trez Bcbg Louis Vuitton Adriana Castro Versus (by Versace) Moschino Jack & Jones Ipanema NYX Helly Hansen Beretta Nars Lee stussy DEELUXE pigalle BOSE Skechers Moncler Japan Rags diamond supply co Tom Ford Alice And Olivia Geographical Norway Fifty Spicy Armani Exchange Roger Dubuis Enza Nucci lancel Aquascutum JBL Napapijri philipp plein Tory Burch Dior IWC Longchamp Rebecca Minkoff Birkenstock Manolo Blahnik Harley Davidson marlboro Kawasaki Bijan KYLIE anti social social club -

Alisa Blanter Design & Direction

EXPERIENCE Freelance | NYC, Boston Designer, 2001-present Worked both on and off site for various clients, including Sesame Workshop, Bath & Body Works, MIT, Nickelodeon, Magnolia Pictures, VIBE Vixen magazine, Segal Savad Design, Hearst Creative Group, and Teen Vogue. ALISA BLANTER Proverb | Boston DESIGN & DIRECTION Senior Art Director, 2016-present www.alisablanter.com Lead the creative team at Proverb, reporting to the Managing Partners. The role oversees the design of logos, websites, signage, collateral, packaging and all other brand supporting — assets for a wide variety of clients in industries, such as real estate, non-profit, health care, interior design, education, retail and the arts. Collaborates with strategy to create initial EDUCATION concepts and design directions. Recruits new designers, reviews and approves all design Massachusetts College of Art produced by the creative team. Graphic Design BFA with Departmental Honors Nickelodeon | NYC Art Director, 2014-2015 — Led a team of designers and freelance vendors to create diverse materials, including SKILLS style guides, logos, packaging and press kits. Managed brand implementation across multiple platforms. Collaborated with VP Creative to establish and provide creative Illustrator, Photoshop, InDesign, and design direction for Nick Jr. properties for internal and external stakeholders. Office, Keynote, Acrobat — Nickelodeon | NYC Associate Art Director, 2010-2014 LANGUAGES Collaborated with the Senior Art Director in establishing and providing the creative English, Russian -

Rob Kohr [email protected] Animation Director 646/408/8505

www.robertkohr.com rob kohr [email protected] animation director 646/408/8505 education School of Visual Arts (1999-2003) Bachelor of Fine Arts (Traditional Animation) • Deans List with Honors, 3.63 grade point average • Silas H. Rhodes Scholarship, Rhodes Family Award for Outstanding Achievement in Animation, Alumni Production Grant filmography The Lift (2010) http://thelift.kohrtoons.com 2d animated short, 4 years in production, directed a staff of 9 artists • $5,000 Seed Grant from MTV Networks for production. • Best Animation at Newport Beach Film Fest, Royal Flush Film Festival Alabama International Film Festival and Philadelphia Independent Film Festival, Sky Fest, Blue Plum Animation Festival, Peach Tree Film Festival and Atlantic City International Film Festival Runner Up Best Short Film at in The Bin Film Festival (Australia) • Finalist or screened at over 55 festivals including Woods Hole Film Festival, Boston Film Festival, Animation Block Party, San Diego Children’s Film Festival, New Orleans Film Festival, Foyle Film Festival, Kinofest, and Ojai Film Festival. SVA Alumni Grant Panel (January 2007 & 2012) • Juror for School of Visual Arts Alumni Society 2007 & 2012 Thesis Grants. Broadcast Design Awards (through Nickelodeon) • Nickelodeon Halloween Logo IDs (Gold Award - 2011) Special Event/Holiday Campaign • Nickjr.com/kids (Gold Award - 2010) flash animation & design • Wonderpets Save the Day (Silver Award - 2007) flash animation • Yo Gabba Gabba Mini Arcade (Nominee - 2008) flash animation • Downward Doghouse Game (Bronze - 2005) flash animation employment Nickelodeon Assoc. Animation Director: On-Air Creative (7/2013 - present) • Co-directed Republic City Hustle, a 9 minute Legend of Korra web short • Animation Direction on Super Duper a preschool animated music video Animator: On-Air Creative (2/2011 - 7/2013) • Storyboarded and created the 3D animated logo IDs and buttons for on-air. -

July 2017 New DVD's

July 2017 New DVD's Title 3 generations A quiet passion Absolutely fabulous : the movie Aftermath Awakening the zodiac Barbie & her sisters in a puppy chase (Motion picture). Barbie, spy squad (Motion picture). Before I fall Bitter harvest Blaze and the monster machines (Television program). Borgias (Television program) Final Season Bug's life (Motion picture) Call the midwife (Television program). Season 6. Chips Collide (Motion picture : 2016). Curious George (Television program). Egg Hunting. Daniel Tiger's neighborhood (Television program). Daniel vists the farm Daniel Tiger's neighborhood (Television program). Daniel's winter wonderland Dinosaur train (Television program). What's at the center of the earth? Dragonball evolution Dragonheart 3 : the sorcerer's curse Elena and the secret of Avalor Existenz Finding Rin Tin Tin Free fire Get out Ghost in the shell Ghost world (Motion picture) Gifted Girls (Television program). Season 4. Good witch. Season one Growing up Smith Hardcore Henry Heavy metal Heavy metal 2000 I am Heath Ledger Impact Keanu (Motion picture) Kill 'em all Kong Kong : Skull Island Life Mickey and the roadster racers. Vol. 1 Mickey Mouse Clubhouse. Mickey's storybook surprises Mindgamers Mine My life as a zucchini NCIS, Los Angeles (Television program). Season 4. NCIS: New Orleans (Television program : 2014 -). Season 2. Norman Olivia Orange is the new black (Television program). Season 2. Outsiders (Television program). Season 2. PAW patrol (Television program). Brave Heros, Big Rescues PJ Masks. Let's go PJ Masks Power Rangers (Motion picture) Psych. The complete fourth season Resident evil, vendetta Rock dog Sid the science kid. Sid's backyard campout Smurfs, the lost village (Motion picture) Song to song Spark Super Why!. -

P32 Layout 1

TV PROGRAMS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 31, 2013 10:30 On The Case With Paula Zahn 11:20 Solved 12:10 Disappeared 13:00 Mystery Diagnosis 03:25 Queens Of The Savannah 03:00 The Hairy Bikers Ride Again 13:50 Street Patrol 04:15 Snow Leopards Of Leafy 03:30 Fantasy Homes By The Sea 14:15 Street Patrol 03:00 The Suite Life Of Zack & Cody London 04:20 The Boss Is Coming To Dinner 14:40 Forensic Detectives 03:20 The Suite Life Of Zack & Cody 04:40 Snow Leopards Of Leafy 04:45 Cash In The Attic 15:30 On The Case With Paula Zahn 03:45 Sonny With A Chance London 05:30 Raymond Blanc’s Kitchen 16:20 Real Emergency Calls 04:05 Sonny With A Chance 05:05 North America Secrets 16:45 Who On Earth Did I Marry? 04:30 Suite Life On Deck 05:55 Animal Kingdom 05:55 Bargain Hunt 17:10 Disappeared 04:50 Suite Life On Deck 06:20 Lion Man: One World African 06:40 Fantasy Homes By The Sea 18:00 Solved 05:15 Wizards Of Waverly Place Safari 07:30 The Boss Is Coming To Dinner 18:50 Forensic Detectives 05:35 Wizards Of Waverly Place 06:45 Animal Airport 08:00 Extreme Makeover: Home 19:40 On The Case With Paula Zahn 06:00 Austin And Ally 07:10 Animal Airport Edition 21:20 Nightmare Next Door 06:25 Austin And Ally 07:35 Call Of The Wildman 08:45 Bargain Hunt 22:10 Couples Who Kill 06:45 A.N.T. -

Disney Channel’S That’S So Raven Is Classified in BARB As ‘Entertainment Situation Comedy US’

Children’s television output analysis 2003-2006 Publication date: 2nd October 2007 ©Ofcom Contents • Introduction • Executive summary • Children’s subgenre range • Children’s subgenre range by channel • Children’s subgenre range by daypart: PSB main channels • Appendix ©Ofcom Introduction • This annex is published as a supplement to Section 2 ‘Broadcaster Output’ of Ofcom’s report The future of children’s television programming. • It provides detail on individual channel output by children’s sub-genre for the PSB main channels, the BBC’s dedicated children’s channels, CBBC and CBeebies, and the commercial children’s channels, as well as detail on genre output by day-part for the PSB main channels. (It does not include any children’s output on other commercial generalist non-terrestrial channels, such as GMTV,ABC1, Sky One.) • This output analysis examines the genre range within children’s programming and looks at how this range has changed since 2003. It is based on the BARB Children’s genre classification only and uses the BARB subgenres of Children’s Drama, Factual, Cartoons, Light entertainment/quizzes, Pre-school and Miscellaneous. • It is important to note that the BARB genre classifications have some drawbacks: – All programme output that is targeted at children is not classified as Children’s within BARB. Some shows targeted at younger viewers, either within children’s slots on the PSB main channels or on the dedicated children’s channels are not classified as Children’s. For example, Disney Channel’s That’s so raven is classified in BARB as ‘Entertainment Situation Comedy US’. This output analysis is not based on the total output of each specific children’s channel, e.g. -

Celebrate an All-Star Nick Jr. Christmas at City Square Mall

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Celebrate an All-star Nick Jr. Christmas at City Square Mall Let an All-star Line-up Take You on a Magical Festive Season Filled with Fun and Gifts! SINGAPORE, 19 September 2016 – Tis the season to revel in a star-studded Christmas as City Square Mall brings you an exciting line-up of characters from popular preschool entertainment brand Nick Jr.! From 18 November 2016 – 1 January 2017, come join characters from Dora the Explorer, PAW Patrol, Blaze and the Monster Machines, Bubble Guppies, Shimmer and Shine and Team Umizoomi as they transform City Square Mall into a dazzling Christmas wonderland! Expect exciting ‘live’ appearances by the celebrated cast of Dora the Explorer and the spunky pups of PAW Patrol who will be joined, for the first time ever in Asia, by Gil and Molly of the Bubble Guppies from 3 – 18 December 2016! Shoppers and their families can look forward to making City Square Mall their one-stop destination for all shopping, dining and gifting needs this festive period as the mall will be all prepped up and set aglow to usher everyone into our favourite time of the year! Here’s all you’ll want for Christmas at City Square Mall: 1. All-star Nick Jr. Wonderland Date: 18 November 2016 to 1 January 2017 Time: 12pm to 10pm daily Venue: L1 City Green (Outdoor Park) Get your party on at City Square Mall’s City Green outdoor park where a playland featuring an array of fun games and activities await you and your family. -

Religion in Children's Visual Media

Journal of Media and Religion ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hjmr20 Religion in Children’s Visual Media: A Qualitative Content Analysis of Preschool Holiday Specials Megan Eide To cite this article: Megan Eide (2020) Religion in Children’s Visual Media: A Qualitative Content Analysis of Preschool Holiday Specials, Journal of Media and Religion, 19:3, 108-126, DOI: 10.1080/15348423.2020.1812339 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15348423.2020.1812339 Published online: 14 Sep 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=hjmr20 JOURNAL OF MEDIA AND RELIGION 2020, VOL. 19, NO. 3, 108–126 https://doi.org/10.1080/15348423.2020.1812339 Religion in Children’s Visual Media: A Qualitative Content Analysis of Preschool Holiday Specials Megan Eide Gustavus Adolphus College ABSTRACT Children adopt lifelong attitudes, behaviors, and beliefs from media messages, yet little is known about what messages visual media send to children on religion. This study addresses this literature gap by analyzing depictions of religion in holiday specials aired in 2018 from three top preschool networks: Disney Junior, Nick Jr., and PBS Kids. Using qualitative content analysis, this study reveals that preschool holiday specials are shifting away from more in-depth portrayals of diverse religions toward commercialized, generalized, and secularized portrayals of Christmas. Although Chanukah and other non-Christmas religious holiday specials are, on average, older and less common than Christmas specials, they portray non-Christmas traditions in greater religious depth than the more recent and numerous Christmas specials portray Christmas. -

Children's DVD Titles (Including Parent Collection)

Children’s DVD Titles (including Parent Collection) - as of July 2017 NRA ABC monsters, volume 1: Meet the ABC monsters NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) PG A.C.O.R.N.S: Operation crack down (CC) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 PG Adventure planet (CC) TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) TV-G Adventures in babysitting (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Top gear trucks TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (2014) (SDH) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) PG The adventures of Panda Warrior (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with -

Cape Coral Daily Breeze

Unbeaten no more CAPE CORAL Cape High loses match to Fort Myers DAILY BREEZE — SPORTS WEATHER: Partly Sunny • Tonight: Mostly Clear • Saturday: Partly Sunny — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 53 Friday, March 6, 2009 50 cents Jury recommends life in prison for Fred Cooper “They’re the heirs to this pain. They’re the ones who Defense pleads for children’s sake want answers. They’re the ones who will have questions. If we kill him, there will be no answers, there will be no By STEVEN BEARDSLEY Cooper on March 16. recalled the lives of the victims, a resolution, there will be nothing.” Special to the Breeze Cooper, 30, convicted of killing young Gateway couple that doted on The state should spare the life of Steven and Michelle Andrews, both their 2-year-old child, and the trou- — Beatriz Taquechel, defense attorney for Fred Cooper convicted murderer Fred Cooper, a 28, showed little reaction to the bled childhood of the convicted, majority of Pinellas County jurors news, despite an emotional day that who grew up without his father and at times brought him to tears. got into trouble fast. stood before jurors and held their “They’re the heirs to this pain. recommended Thursday. pictures aloft, one in each hand. One They’re the ones who want Lee County Judge Thomas S. Jurors were asked to weigh the In the end, the argument for case for Cooper’s death with a pas- Cooper’s life was the lives of the was of the Andrewses’ 2-year-old answers,” Taquechel pleaded.