Religion in Children's Visual Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

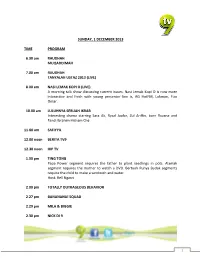

1 SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 Am

SUNDAY, 1 DECEMBER 2013 TIME PROGRAM 6.30 am RAUDHAH MUQADDIMAH 7.00 am RAUDHAH TANYALAH USTAZ 2013 (LIVE) 8.00 am NASI LEMAK KOPI O (LIVE) A morning talk show discussing current issues. Nasi Lemak Kopi O is now more interactive and fresh with young presenter line is, AG HotFM, Lokman, Fizo Omar. 10.00 am LULUHNYA SEBUAH IKRAR Interesting drama starring Sara Ali, Ryzal Jaafar, Zul Ariffin, born Ruzana and Fandi Ibrahim Hisham Che 11.00 am SAFIYYA 12.00 noon BERITA TV9 12.30 noon HIP TV 1.00 pm TING TONG Papa Power segment requires the father to plant seedlings in pots. Alamak segment requires the mother to watch a DVD. Bertuah Punya Budak segments require the child to make a sandwich and water. Host: Bell Ngasri 2.00 pm TOTALLY OUTRAGEOUS BEHAVIOR 2.27 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 2.29 pm MILA & BIGGIE 2.30 pm NICK DI 9 1 TEAM UMIZOOMI 3.00 pm NICK DI 9 DORA THE EXPLORER 3.30 pm NICK DI 9 ADVENTURES OF JIMMY NEUTRONS 4.00 pm NICK DI 9 PLANET SHEEN 4.30 pm NICK DI 9 AVATAR THE LEGEND OF AANG 5.00 pm NICK DI 9 SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS 5.28 pm BANANANA! SQUAD 5.30 pm BOLA KAMPUNG THE MOVIE Amanda is a princess who comes from the virtual world of a game called "Kingdom Hill '. She was sent to the village to find Pewira Suria, the savior who can end the current crisis. Cast: Harris Alif, Aizat Amdan, Harun Salim Bachik, Steve Bone, Ezlynn 7.30 pm SWITCH OFF 2 The Award Winning game show returns with a new twist! Hosted by Rockstar, Radhi OAG, and the game challenges bands with a mission to save their band members from the Mysterious House in the Woods. -

Victoria P. 4 JAN FEB 17

Victoria p. 4 JAN FEB 17 For Members of the Nine Network of Public Media SCC1634_MainCampus_Neuro-Onc_NINEMag-OL.indd 1 7/27/16 1:11 PM January–February 2017 Contents Volume 8, Number 1 Page 4 Victoria The Nine Network Program Guide 2 Photo Montage 17 January Listings 3 Message from the President 25 January Prime Time 4 Drama Queen 26 Create The new miniseries Victoria premieres January 15. 27 World 6 New on Nine 28 February Listings Starting January 16, Nine PBS KIDS will take the place of 35 February Prime Time the Nine Kids channel and include online streaming and Repeat Schedule interactive gaming. 36 In Memoriam: Gwen Ifill and Eugene Mackey, III 8 On the cover: Actress Jenna Coleman plays Queen Victoria, who at age 18 is awakened one morning and 9 Nine Networking informed she is now queen of England. Photo courtesy of Your videos and photos in the Public Media Commons. • ITV Studios Global Entertainment. A one-hour, live Donnybrook special airs January 5. • By Above: Victoria offers grand sets, lush countryside, castle activating your Nine Passport account, you will have access intrigue and a study of lives that shaped history. Photo courtesy of ITV Studios Global Entertainment. to thousands of episodes online. • Nine receives honors. • Nine takes the St. Louis Symphony beyond Powell Hall. • Our Wednesday night film series continues in 2017. • New season Nine Network Director of Marketing 3655 Olive St. and Communications of America's Test Kitchen. St. Louis, MO 63108 Matt Huelskamp (314) 512-9000 Editor Inspiring the Spirit of Possibility Fax (314) 512-9005 16 Lynanne Feilen Your contribution to the Nine Network is a gift to the community. -

Nickelodeon Previews New Content Pipeline for 2014-2015 Season at Annual Upfront Presentation

Nickelodeon Previews New Content Pipeline for 2014-2015 Season at Annual Upfront Presentation Nick to Add 10 New Series to Schedule, with Content Spanning Every Genre, Every Platform Network Unveils Plans for Brand-New, Live Tent-Pole Event, Kids' Choice Sports 2014; Host/Executive Producer Michael Strahan Details Show Slated for 3Q 2014 Upfront Presentation Capped by Special Musical Performance from Five-Time Grammy Nominee Sara Bareilles NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Nickelodeon held its annual upfront presentation today at Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City, where Nickelodeon Group President Cyma Zarghami detailed the network's biggest content pipeline ever: 10 new series across every genre, and for every platform—all tailor-made for the tastes of today's post-millennial generation of kids. Zarghami also announced plans for the forthcoming Nick Jr. App, featuring TV Everywhere capability, and the brand-new, live tent-pole event, Kids' Choice Sports—the first-ever expansion of the highly successful Kids' Choice Awards franchise. Nickelodeon's presentation was also punctuated by remarks from Viacom Chairman Philippe Dauman; an appearance by Kids' Choice Sports 2014 host and executive producer Michael Strahan; and a closing musical performance from five-time Grammy nominee Sara Bareilles. "Our mission has been to create and deliver funny content that will resonate with today's kids, and we are well-positioned to do that through our schedule of fresh hits, a deep pipeline of new series, tent-pole events, ratings momentum and innovation on all platforms," said Zarghami. "Nickelodeon is a magnet for creative people and projects, and we're incredibly excited about the new pool of talent we're bringing to our audience in front of and behind the camera." Nickelodeon has posted 13 straight months of year-over-year growth and reclaimed the top spot with kids in 4Q13. -

Brand Armani Jeans Celebry Tees Rochas Roberto Cavalli Capcho

Brand Armani Jeans Celebry Tees Rochas Roberto Cavalli Capcho Lady Million Just Over The Top Tommy Hilfiger puma TJ Maxx YEEZY Marc Jacobs British Knights ROSALIND BREITLING Polo Vicuna Morabito Loewe Alexander Wang Kenzo Redskins Little Marcel PIGUET Emu Affliction Bensimon valege Chanel Chance Swarovski RG512 ESET Omega palace Serge Pariente Alpinestars Bally Sven new balance Dolce & Gabbana Canada Goose thrasher Supreme Paco Rabanne Lacoste Remeehair Old Navy Gucci Fjallraven Zara Fendi allure bridals BLEU DE CHANEL LensCrafters Bill Blass new era Breguet Invictus 1 million Trussardi Le Coq Sportif Balenciaga CIBA VISION Kappa Alberta Ferretti miu miu Bottega Veneta 7 For All Mankind VERNEE Briston Olympea Adidas Scotch & Soda Cartier Emporio Armani Balmain Ralph Lauren Edwin Wallace H&M Kiss & Walk deus Chaumet NAKED (by URBAN DECAY) Benetton Aape paccbet Pantofola d'Oro Christian Louboutin vans Bon Bebe Ben Sherman Asfvlt Amaya Arzuaga bulgari Elecoom Rolex ASICS POLO VIDENG Zenith Babyliss Chanel Gabrielle Brian Atwood mcm Chloe Helvetica Mountain Pioneers Trez Bcbg Louis Vuitton Adriana Castro Versus (by Versace) Moschino Jack & Jones Ipanema NYX Helly Hansen Beretta Nars Lee stussy DEELUXE pigalle BOSE Skechers Moncler Japan Rags diamond supply co Tom Ford Alice And Olivia Geographical Norway Fifty Spicy Armani Exchange Roger Dubuis Enza Nucci lancel Aquascutum JBL Napapijri philipp plein Tory Burch Dior IWC Longchamp Rebecca Minkoff Birkenstock Manolo Blahnik Harley Davidson marlboro Kawasaki Bijan KYLIE anti social social club -

Alisa Blanter Design & Direction

EXPERIENCE Freelance | NYC, Boston Designer, 2001-present Worked both on and off site for various clients, including Sesame Workshop, Bath & Body Works, MIT, Nickelodeon, Magnolia Pictures, VIBE Vixen magazine, Segal Savad Design, Hearst Creative Group, and Teen Vogue. ALISA BLANTER Proverb | Boston DESIGN & DIRECTION Senior Art Director, 2016-present www.alisablanter.com Lead the creative team at Proverb, reporting to the Managing Partners. The role oversees the design of logos, websites, signage, collateral, packaging and all other brand supporting — assets for a wide variety of clients in industries, such as real estate, non-profit, health care, interior design, education, retail and the arts. Collaborates with strategy to create initial EDUCATION concepts and design directions. Recruits new designers, reviews and approves all design Massachusetts College of Art produced by the creative team. Graphic Design BFA with Departmental Honors Nickelodeon | NYC Art Director, 2014-2015 — Led a team of designers and freelance vendors to create diverse materials, including SKILLS style guides, logos, packaging and press kits. Managed brand implementation across multiple platforms. Collaborated with VP Creative to establish and provide creative Illustrator, Photoshop, InDesign, and design direction for Nick Jr. properties for internal and external stakeholders. Office, Keynote, Acrobat — Nickelodeon | NYC Associate Art Director, 2010-2014 LANGUAGES Collaborated with the Senior Art Director in establishing and providing the creative English, Russian -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

FCC-19-67A Notice of Proposed Rulemaking Re

Federal Communications Commission FCC 19-67 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Children’s Television Programming Rules ) MB Docket No. 18-202 ) Modernization of Media Regulation Initiative ) MB Docket No. 17-105 REPORT AND ORDER AND FURTHER NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING Adopted: July 10, 2019 Released: July 12, 2019 Comment Date: (30 days after date of publication in the Federal Register) Reply Comment Date: (60 days after date of publication in the Federal Register) By the Commission: Chairman Pai and Commissioners O’Rielly and Carr issuing separate statements; Commissioners Rosenworcel and Starks dissenting and issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND.....................................................................................................................................3 III. DISCUSSION........................................................................................................................................10 A. Statutory Authority .........................................................................................................................10 B. The Current State of the Marketplace for Children’s Programming ..............................................11 C. Core Programming..........................................................................................................................21 -

„JETIX“ Aktenzeichen: KEK 503 Beschluss in Der Rundfu

Zulassungsantrag der Jetix Europe GmbH für das Fernsehspartenprogramm „JETIX“ Aktenzeichen: KEK 503 Beschluss In der Rundfunkangelegenheit der Jetix Europe GmbH, vertreten durch die Geschäftsführer Jürgen Hinz, Stefan Kas- tenmüller, Dene Stratton und Paul D. Taylor, Infanteriestraße 19/6, 80797 München, – Antragstellerin – w e g e n Zulassung zur bundesweiten Veranstaltung des Fernsehspartenprogramms „JETIX“ hat die Kommission zur Ermittlung der Konzentration im Medienbereich (KEK) auf Vorlagen der Bayerischen Landeszentrale für neue Medien (BLM) vom 02.06.2008 in der Sitzung am 19.08.2008 unter Mitwirkung ihrer Mitglieder Prof. Dr. Sjurts (Vorsitzende), Prof. Dr. Huber, Dr. Lübbert und Prof. Dr. Mailänder entschieden: Der von der Jetix Europe GmbH mit Schreiben vom 21.05.2008 bei der Bayeri- schen Landeszentrale für neue Medien (BLM) beantragten Zulassung zur Veran- staltung des bundesweit verbreiteten Fernsehspartenprogramms JETIX stehen Gründe der Sicherung der Meinungsvielfalt im Fernsehen nicht entgegen. 2 Begründung I Sachverhalt 1 Zulassungsantrag Die Antragstellerin hat mit Schreiben vom 21.05.2008 bei der BLM die Verlänge- rung der zum 30.09.2008 auslaufenden Zulassung für das Fernsehspartenpro- gramm JETIX um weitere acht Jahre beantragt. Die BLM hat der KEK den Antrag mit Schreiben vom 02.06.2008 zur medienkonzentrationsrechtlichen Prüfung vorge- legt. 2 Programmstruktur und -verbreitung 2.1 JETIX ist ein deutschsprachiges, digitales Spartenprogramm für Kinder mit dem Schwerpunkt auf Unterhaltung. Gesendet werden täglich von 06:00 bis 19:45 Uhr Action-, Humor- und Abenteuerformate. Die Zielgruppe sind Kinder im Alter zwi- schen 6 und 14 Jahren. 2.2 JETIX wird als Pay-TV-Angebot verschlüsselt und digital über die Programmplatt- form der Premiere Fernsehen GmbH & Co. -

Disney Channel’S That’S So Raven Is Classified in BARB As ‘Entertainment Situation Comedy US’

Children’s television output analysis 2003-2006 Publication date: 2nd October 2007 ©Ofcom Contents • Introduction • Executive summary • Children’s subgenre range • Children’s subgenre range by channel • Children’s subgenre range by daypart: PSB main channels • Appendix ©Ofcom Introduction • This annex is published as a supplement to Section 2 ‘Broadcaster Output’ of Ofcom’s report The future of children’s television programming. • It provides detail on individual channel output by children’s sub-genre for the PSB main channels, the BBC’s dedicated children’s channels, CBBC and CBeebies, and the commercial children’s channels, as well as detail on genre output by day-part for the PSB main channels. (It does not include any children’s output on other commercial generalist non-terrestrial channels, such as GMTV,ABC1, Sky One.) • This output analysis examines the genre range within children’s programming and looks at how this range has changed since 2003. It is based on the BARB Children’s genre classification only and uses the BARB subgenres of Children’s Drama, Factual, Cartoons, Light entertainment/quizzes, Pre-school and Miscellaneous. • It is important to note that the BARB genre classifications have some drawbacks: – All programme output that is targeted at children is not classified as Children’s within BARB. Some shows targeted at younger viewers, either within children’s slots on the PSB main channels or on the dedicated children’s channels are not classified as Children’s. For example, Disney Channel’s That’s so raven is classified in BARB as ‘Entertainment Situation Comedy US’. This output analysis is not based on the total output of each specific children’s channel, e.g. -

Cinematic Specific Voice Over

CINEMATIC SPECIFIC PROMOS AT THE MOVIES BATES MOTEL BTS A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS CHOZEN S1 --- IN THEATER "TURN OFF CELL PHONE" MESSAGE FX NETWORKS E!: BELL MEDIA WHISTLER FILM FESTIVAL TRAILER BELL MEDIA AGENCY FALLING SKIES --- CLEAR GAZE TEASE TNT HOUSE OF LIES: HANDSHAKE :30 SHOWTIME VOICE OVER BEST VOICE OVER PERFORMANCE ALEXANDER SALAMAT FOR "GENERATIONS" & "BURNOUT" ESPN ANIMANIACS LAUNCH THE HUB NETWORK JUNE STUNT SPOT SHOWTIME LEADERSHIP CNN NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL SUMMER IMAGE "LIFE" SHAW MEDIA INC. Page 1 of 68 TELEVISION --- VIDEO PRESENTATION: CHANNEL PROMOTION GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT GENERIC :45 RED CARPET IMAGE FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY HAPPY DAYS FOX SPORTS MARKETING HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA MUCH: TMC --- SERENA RYDER BELL MEDIA AGENCY SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN COMPETITIVE CAMPAIGN DIRECTV DISCOVERY BRAND ANTHEM DISCOVERY, RADLEY, BIGSMACK FOX SPORTS 1 LAUNCH CAMPAIGN FOX SPORTS MARKETING LAUNCH CAMPAIGN PIVOT THE HUB NETWORK'S SUMMER CAMPAIGN THE HUB NETWORK ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT BRAG PHOTOBOOTH CBS TELEVISION NETWORK BRAND SPOT A&E TELEVISION NETWORKS Page 2 of 68 NBC 2013 SEASON NBCUNIVERSAL SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND :60 BRAVO ZTÉLÉ – HOSTS BELL MEDIA INC. ART DIRECTION & DESIGN: GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE CAMPAIGN NICKELODEON HALLOWEEN IDS 2013 NICKELODEON HOLIDAY CAMPAIGN TELEMUNDO MEDIA NICKELODEON KNIT HOLIDAY IDS 2013 NICKELODEON SUMMER BY BRAVO DESERT ISLAND CAMPAIGN BRAVO NICKELODEON SUMMER IDS 2013 NICKELODEON GENERAL CHANNEL IMAGE SPOT --- LONG FORMAT "WE ARE IT" NUVOTV AN AMERICAN COACH IN LONDON NBC SPORTS AGENCY GENERIC: FBC COALITION SIZZLE (1:49) FOX BROADCASTING COMPANY PBS UPFRONT SIZZLE REEL PBS Page 3 of 68 WHAT THE FOX! FOX BROADCASTING CO. -

Federal Communications Commission FCC 19-67 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 in the Matter Of

Federal Communications Commission FCC 19-67 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Children’s Television Programming Rules ) MB Docket No. 18-202 ) Modernization of Media Regulation Initiative ) MB Docket No. 17-105 REPORT AND ORDER AND FURTHER NOTICE OF PROPOSED RULEMAKING Adopted: July 10, 2019 Released: July 12, 2019 Comment Date: (30 days after date of publication in the Federal Register) Reply Comment Date: (60 days after date of publication in the Federal Register) By the Commission: Chairman Pai and Commissioners O’Rielly and Carr issuing separate statements; Commissioners Rosenworcel and Starks dissenting and issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND.....................................................................................................................................3 III. DISCUSSION........................................................................................................................................10 A. Statutory Authority .........................................................................................................................10 B. The Current State of the Marketplace for Children’s Programming ..............................................11 C. Core Programming..........................................................................................................................21 -

Happily Ever Ancient

HAPPILY EVER ANCIENT Visions of Antiquity for children in visual media HAPPILY EVER ANCIENT This work is subject to an International Creative Commons License Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0, for a copy visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Visions of Antiquity for children in visual media First Edition, December 2020 ...still facing COVID-19. Editor: Asociación para la Investigación y la Difusión de la Arqueología Pública, JAS Arqueología Plaza de Mondariz, 6 28029 - Madrid www.jasarqueologia.es Attribution: In each chapter Cover: Jaime Almansa Sánchez, from nuptial lebetes at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Greece. ISBN: 978-84-16725-32-8 Depósito Legal: M-29023-2020 Printer: Service Pointwww.servicepoint.es Impreso y hecho en España - Printed and made in Spain CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: A CONTEMPORARY ANTIQUITY FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG AUDIENCES IN FILMS AND CARTOONS Julián PELEGRÍN CAMPO 1 FAMILY LOVE AND HAPPILY MARRIAGES: REINVENTING MYTHICAL SOCIETY IN DISNEY’S HERCULES (1997) Elena DUCE PASTOR 19 OVER 5,000,000.001: ANALYZING HADES AND HIS PEOPLE IN DISNEY’S HERCULES Chiara CAPPANERA 41 FROM PLATO’S ATLANTIS TO INTERESTELLAR GATES: THE DISTORTED MYTH Irene CISNEROS ABELLÁN 61 MOANA AND MALINOWSKI: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACH TO MODERN ANIMATION Emma PERAZZONE RIVERO 79 ANIMATING ANTIQUITY ON CHILDREN’S TELEVISION: THE VISUAL WORLDS OF ULYSSES 31 AND SAMURAI JACK Sarah MILES 95 SALPICADURAS DE MOTIVOS CLÁSICOS EN LA SERIE ONE PIECE Noelia GÓMEZ SAN JUAN 113 “WHAT A NOSE!” VISIONS OF CLEOPATRA AT THE CINEMA & TV FOR CHILDREN AND TEENAGERS Nerea TARANCÓN HUARTE 135 ONCE UPON A TIME IN MACEDON.