Mr. Capra Goes to Washington Author(S): Michael P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers t was 1946 and film noir was everywhere, counter, The Jolson Story, Notorious, The and into the 70s and 80s, including King of from low budget quickies to major studio Spiral Stair-case, Anna and the King of Kings, El Cid, Sodom and Gomorrah, The Ireleases. Of course, the studios didn’t re - Siam , and more, so it’s no wonder that The V.I.P.s, The Power, The Private Life of Sher - alize they were making films noir, since that Strange Love of Martha Ivers got lost in the lock Holmes (for Wilder again), The Golden term had just been coined in 1946 by shuffle. It did manage to sneak in one Acad - Voyage of Sinbad, Providence, Fedora French film critic, Nino Frank. The noirs of emy Award nomination for John Patrick (Wilder again), Last Embrace, Time after 1946 included: The Killers, The Blue Dahlia, (Best Writing, Original Story), but he lost to Time, Eye of the Needle , Dead Men Don’t The Big Sleep, Gilda, The Postman Always Clemence Dane for Vacation from Marriage Wear Plaid and more. It’s one of the most Rings Twice, The Stranger, The Dark Mirror, (anyone heard of that one since?). impressive filmographies of any film com - The Black Angel , and The Strange Love of poser in history, and along the way he gar - Martha Ivers. When Martha Ivers, young, orphaned nered an additional six Oscar nominations heiress to a steel mill, is caught running and another two wins. The Strange Love of Martha Ivers was an away with her friend, she’s returned home “A” picture from Paramount, produced by to her aunt, whom she hates. -

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Understanding Screenwriting'

Course Materials for 'Understanding Screenwriting' FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 Evan Wm. Cameron Professor Emeritus Senior Scholar in Screenwriting Graduate Programmes, Film & Video and Philosophy York University [Overview, Outline, Readings and Guidelines (for students) with the Schedule of Lectures and Screenings (for private use of EWC) for an extraordinary double-weighted full- year course for advanced students of screenwriting, meeting for six hours weekly with each term of work constituting a full six-credit course, that the author was permitted to teach with the Graduate Programme of the Department of Film and Video, York University during the academic years 2001-2002 and 2002-2003 – the most enlightening experience with respect to designing movies that he was ever permitted to share with students.] Overview for Graduate Students [Preliminary Announcement of Course] Understanding Screenwriting FA/FILM 4501 12.0 Fall and Winter Terms 2002-2003 FA/FILM 4501 A 6.0 & FA/FILM 4501 B 6.0 Understanding Screenwriting: the Studio and Post-Studio Eras Fall/Winter, 2002-2003 Tuesdays & Thursdays, Room 108 9:30 a.m. – 1:30 p.m. Evan William Cameron We shall retrace within these courses the historical 'devolution' of screenwriting, as Robert Towne described it, providing advanced students of writing with the uncommon opportunity to deepen their understanding of the prior achievement of other writers, and to ponder without illusion the nature of the extraordinary task that lies before them should they decide to devote a part of their life to pursuing it. During the fall term we shall examine how a dozen or so writers wrote within the studio system before it collapsed in the late 1950s, including a sustained look at the work of Preston Sturges. -

Филмð¾ð³ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑ)

Франк Капра Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ) The Broadway Madonna https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-broadway-madonna-3986111/actors Platinum Blonde https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/platinum-blonde-1124332/actors Prelude to War https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/prelude-to-war-1144659/actors That Certain Thing https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/that-certain-thing-1157116/actors Rain or Shine https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rain-or-shine-1157168/actors State of the Union https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/state-of-the-union-1198352/actors Tunisian Victory https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/tunisian-victory-12129859/actors Pocketful of Miracles https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/pocketful-of-miracles-1219727/actors The Battle of Russia https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-battle-of-russia-1387285/actors Meet John Doe https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/meet-john-doe-1520732/actors Tramp, Tramp https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/tramp%2C-tramp-1540242/actors Lost Horizon https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/lost-horizon-1619885/actors Here Comes the Groom https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/here-comes-the-groom-1622567/actors Rendezvous in Space https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rendezvous-in-space-17027654/actors Ladies of Leisure https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ladies-of-leisure-1799948/actors The Miracle Woman https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-miracle-woman-1808053/actors Flight https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/flight-2032557/actors -

1 Small Wonder Philip Horne DOWNSIZING

1 Small Wonder Philip Horne DOWNSIZING [February 2018, Sight & Sound] There has been a long and somewhat anxious wait among admirers of Alexander Payne’s films since Nebraska in 2013 – a bleak, beautiful, drily funny picture of the post-industrial Midwest and sad, haunted lives. Four years later Payne, who still lives in his native Omaha, has come out with a grand, astonishingly daring movie – a satirical fable, or blackly comic science fiction epic, or unexpected love story. As it goes on, there’s a serious, even tragic side to the film, but its main premise is treated with such inventiveness both visual and verbal that we get constant jolts of pleasure at the imaginative scope of its makers’ conceptions. The absurd technology that scientists concerned with ‘Human Scale and Sustainability’ and climate change develop for reducing the size of the human population – by making them five inches high – is in effect like a giant microwave: it even pings when the transformation is complete. It’s deliberately low-tech. The process, invented by idealistic Norwegians to produce a ‘self- sustainable community of the small’, is imagined being then commercialised and normalised in familiar ways by global/American capitalism, sold to punters as a time-share-like ‘heaven’ called ‘Leisureland’, which is ‘like winning the lottery every day’. This because a modest nest-egg of $152,000 when transferred (unshrunk) to its newly-tiny owner’s account in a ‘small city’ translates as the equivalent of $22,5000,000: it’s an American dream. The script is full of delicious size jokes, as downsizing becomes absorbed into idiom and things get re-scaled, so that we see ‘the first small baby ever born’. -

Scorses by Ebert

Scorsese by Ebert other books by An Illini Century roger ebert A Kiss Is Still a Kiss Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook Behind the Phantom’s Mask Roger Ebert’s Little Movie Glossary Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion annually 1986–1993 Roger Ebert’s Video Companion annually 1994–1998 Roger Ebert’s Movie Yearbook annually 1999– Questions for the Movie Answer Man Roger Ebert’s Book of Film: An Anthology Ebert’s Bigger Little Movie Glossary I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie The Great Movies The Great Movies II Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert Your Movie Sucks Roger Ebert’s Four-Star Reviews 1967–2007 With Daniel Curley The Perfect London Walk With Gene Siskel The Future of the Movies: Interviews with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas DVD Commentary Tracks Beyond the Valley of the Dolls Casablanca Citizen Kane Crumb Dark City Floating Weeds Roger Ebert Scorsese by Ebert foreword by Martin Scorsese the university of chicago press Chicago and London Roger Ebert is the Pulitzer The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 Prize–winning film critic of the Chicago The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London Sun-Times. Starting in 1975, he cohosted © 2008 by The Ebert Company, Ltd. a long-running weekly movie-review Foreword © 2008 by The University of Chicago Press program on television, first with Gene All rights reserved. Published 2008 Siskel and then with Richard Roeper. He Printed in the United States of America is the author of numerous books on film, including The Great Movies, The Great 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 Movies II, and Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert, the last published by the ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18202-5 (cloth) University of Chicago Press. -

Mean Streets: Death and Disfiguration in Hawks's Scarface

Mean Streets: Death and Disfiguration in Hawks's Scarface ASBJØRN GRØNSTAD Consider this paradox: in Howard Hawks' Scarface, The Shame of the Nation, violence is virtually all-encompassing, yet it is a film from an era before American movies really got violent. There are no graphic close-ups of bullet wounds or slow-motion dissection of agonized faces and bodies, only a series of abrupt, almost perfunctory liquidations seemingly devoid of the heat and passion that characterize the deaths of the spastic Lyle Gotch in The Wild Bunch or the anguished Mr. Orange, slowly bleeding to death, in Reservoir Dogs. Nonetheless, as Bernie Cook correctly points out, Scarface is the most violent of all the gangster films of the eatly 1930s cycle (1999: 545).' Hawks's camera desists from examining the anatomy of the punctured flesh and the extended convulsions of corporeality in transition. The film's approach, conforming to the period style of ptc-Bonnie and Clyde depictions of violence, is understated, euphemistic, in its attention to the particulars of what Mark Ledbetter sees as "narrative scarring" (1996: x). It would not be illegitimate to describe the form of violence in Scarface as discreet, were it not for the fact that appraisals of the aesthetics of violence are primarily a question of kinds, and not degrees. In Hawks's film, as we shall see, violence orchestrates the deep structure of the narrative logic, yielding an hysterical form of plotting that hovers between the impulse toward self- effacement and the desire to advance an ethics of emasculation. Scarface is a film in which violence completely takes over the narrative, becoming both its vehicle and its determination. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

Visit Imdb.Com for Up-To-The-Minute Academy Award Updates, and View

NOMINEES FOR THE 84th ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS Best Motion Picture of the Year Best Animated Feature Film Best Achievement in Sound Mixing The Artist (2011): Thomas Langmann of the Year The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011): David Parker, The Descendants (2011): Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, A Cat in Paris (2010): Alain Gagnol, Jean-Loup Felicioli Michael Semanick, Ren Klyce, Bo Persson Jim Taylor Chico & Rita (2010): Fernando Trueba, Javier Mariscal Hugo (2011/II): Tom Fleischman, John Midgley Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (2011): Scott Rudin Kung Fu Panda 2 (2011): Jennifer Yuh Moneyball (2011): Deb Adair, Ron Bochar, The Help (2011): Brunson Green, Chris Columbus, Puss in Boots (2011): Chris Miller David Giammarco, Ed Novick Michael Barnathan Rango (2011): Gore Verbinski Transformers: Dark of the Moon (2011): Greg P. Russell, Hugo (2011/II): Graham King, Martin Scorsese Gary Summers, Jeffrey J. Haboush, Peter J. Devlin Midnight in Paris (2011): Letty Aronson, Best Foreign Language Film War Horse (2011): Gary Rydstrom, Andy Nelson, Tom Stephen Tenenbaum of the Year Johnson, Stuart Wilson Moneyball (2011): Michael De Luca, Rachael Horovitz, Bullhead (2011): Michael R. Roskam(Belgium) Best Achievement in Sound Editing Brad Pitt Footnote (2011): Joseph Cedar(Israel) The Tree of Life (2011): Nominees to be determined In Darkness (2011): Agnieszka Holland(Poland) Drive (2011): Lon Bender, Victor Ray Ennis War Horse (2011): Steven Spielberg, Kathleen Kennedy Monsieur Lazhar (2011): Philippe Falardeau(Canada) The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo -

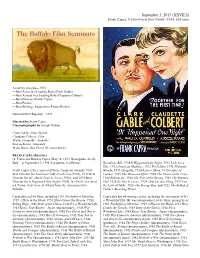

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 Min)

September 3, 2013 (XXVII:2) Frank Capra, IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934, 105 min) Academy Awards—1935: —Best Actor in a Leading Role (Clark Gable) —Best Actress in a Leading Role (Claudette Colbert) —Best Director (Frank Capra) —Best Picture —Best Writing, Adaptation (Robert Riskin) National Film Registry—1993 Directed by Frank Capra Cinematography by Joseph Walker Clark Gable...Peter Warne Claudette Colbert...Ellie Walter Connolly...Andrews Roscoe Karns...Shapeley Ward Bond...Bus Driver #1 (uncredited) FRANK CAPRA (director) (b. Francesco Rosario Capra, May 18, 1897, Bisacquino, Sicily, Italy—d. September 3, 1991, La Quinta, California) Broadway Bill, 1934 It Happened One Night, 1933 Lady for a Day, 1932 American Madness, 1932 Forbidden, 1931 Platinum Frank Capra is the recipient of three Academy Awards: 1939 Blonde, 1931 Dirigible, 1930 Rain or Shine, 1930 Ladies of Best Director for You Can't Take It with You (1938), 1937 Best Leisure, 1929 The Donovan Affair, 1928 The Power of the Press, Director for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), and 1935 Best 1928 Submarine, 1928 The Way of the Strong, 1928 The Matinee Director for It Happened One Night (1934). In 1982 he received Idol, 1928 So This Is Love?, 1928 That Certain Thing, 1927 For a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film the Love of Mike, 1926 The Strong Man, and 1922 The Ballad of Institute. Fisher's Boarding House. Capra directed 54 films, including 1961 Pocketful of Miracles, Capra also has 44 writing credits, including the screenplay of It’s 1959 A Hole in the Head, 1951 Here Comes the Groom, 1950 a Wonderful Life. -

Book Vs. Film: LA CHIENNE Vs. SCARLET STREET

BOOK VS FILM Brian Light author’s commentary on the incestuous bed- counterpoint to the plotline. The book is fellows of art and commerce. frank in its depiction of the sordid relation- ew French writers in the first In his preface, de la Fouchardière calls ship between Lulu and Dédé and the pseudo half of the 20th century could attention to the theatrical staging used to romantic/financial arrangement between rival the output of Georges de set up the narrative structure of the story: Lulu and Legrand. la Fouchardière. He produced “I have chosen a technique borrowed from In 1931, Jean Renoir adapted the book 33 humorous novels and crime dramatic art…each of the characters who to the screen with the same title. An early Fthrillers, over a dozen of which were adapted participate in the story will in turn take the example of poetic realism, this was only for the screen in the 1920s and ’30s. He was a stage and tell in his own way about events Renoir’s second talking picture, and, to his prodigious journalist and devout pacifist who in which he has been implicated.” In chap- credit, he shot the entire film using actual covered WWI and WWII for two newspapers, ters titled “He,” “She,” and “The Other,” Parisian street locations. The preceding year La Vague and Paris-Soir, and he also wrote a we are provided with three distinct points of Alfred Knopf published an English transla- column for the weekly journal Paris-Sport. In view. “He” (Maurice Legrand) is the princi- tion of La Chienne, titled Poor Sap, which 1929, he published La Chienne (The Bitch), pal storyteller, and, as such, he is depicted enjoyed a second printing. -

Gorinski2018.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Automatic Movie Analysis and Summarisation Philip John Gorinski I V N E R U S E I T H Y T O H F G E R D I N B U Doctor of Philosophy Institute for Language, Cognition and Computation School of Informatics University of Edinburgh 2017 Abstract Automatic movie analysis is the task of employing Machine Learning methods to the field of screenplays, movie scripts, and motion pictures to facilitate or enable vari- ous tasks throughout the entirety of a movie’s life-cycle. From helping with making informed decisions about a new movie script with respect to aspects such as its origi- nality, similarity to other movies, or even commercial viability, all the way to offering consumers new and interesting ways of viewing the final movie, many stages in the life-cycle of a movie stand to benefit from Machine Learning techniques that promise to reduce human effort, time, or both.