Medical Care in Urban Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EU and Member States' Policies and Laws on Persons Suspected Of

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT C: CITIZENS’ RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS CIVIL LIBERTIES, JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS EU and Member States’ policies and laws on persons suspected of terrorism- related crimes STUDY Abstract This study, commissioned by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the European Parliament Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE Committee), presents an overview of the legal and policy framework in the EU and 10 select EU Member States on persons suspected of terrorism-related crimes. The study analyses how Member States define suspects of terrorism- related crimes, what measures are available to state authorities to prevent and investigate such crimes and how information on suspects of terrorism-related crimes is exchanged between Member States. The comparative analysis between the 10 Member States subject to this study, in combination with the examination of relevant EU policy and legislation, leads to the development of key conclusions and recommendations. PE 596.832 EN 1 ABOUT THE PUBLICATION This research paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs and was commissioned, overseen and published by the Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs. Policy Departments provide independent expertise, both in-house and externally, to support European Parliament committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation -

DEALING with JIHADISM a Policy Comparison Between the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France, the UK and the US (2010 to 2017)

DEALING WITH JIHADISM A policy comparison between the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France, the UK and the US (2010 to 2017) Stef Wittendorp, Roel de Bont, Jeanine de Roy van Zuijdewijn and Edwin Bakker ISGA Report Dealing with jihadism: A policy comparison between the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France, the UK, and the US (2010 to 2017) Stef Wittendorp, Roel de Bont, Jeanine de Roy van Zuijdewijn and Edwin Bakker December 2017 (the research was completed in October 2016) ISSN 2452-0551 e-ISSN 2452-056X © 2017, Stef Wittendorp / Roel de Bont / Jeanine de Roy van Zuijdewijn / Edwin Bakker / Leiden University Cover design: Oscar Langley www.oscarlangley.com All rights reserved. Without limiting the right under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without prior permission of both the copyright owners Leiden University and the authors of the book. Table of Contents List with abbreviations................................................................................................ 5 List with tables and figures ....................................................................................... 10 Summary .................................................................................................................. 11 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 13 2 -

1: Introduction

Working Papers WP 2018-04 Centre for German and European Studies (CGES) Daria Kuklinskaia Social and political factors of the anti-terrorist legislation development: Cases of the United Kingdom, Germany and Russia WP 2018-04 2018 № 4 Bielefeld / St. Petersburg Working Papers WP 2018-04 Centre for German and European Studies Bielefeld University St. Petersburg State University Centre for German and European Studies (CGES) CGES Working Papers series includes publication of materials prepared within different activities of the Centre for German and European Studies both in St. Petersburg and in Germany. The CGES supports educational programmes, research and scientific dialogues. In accordance with the CGES mission, the Working Papers are dedicated to the interdisciplinary studies of different aspects of German and European societies. The paper is based on an MA thesis defended at the MA 'Studies in European Societies' in June 2018 and supervised by Dr. Elena Belokurova. This paper is dedicated to the analysis of the social and political factors that could have influenced anti-terrorist legislation development (by the examples of the United Kingdom, Germany and Russia). The political factors that were analyzed include the international obligations imposed on the countries by the international conventions and treaties, whereas social factors that were researched are the internal and external shocks and policy-oriented learning processes. The paper also puts a special emphasis on the comparative analysis of the contemporary anti-terrorist legislations in the chosen countries (since the end of 1990s until 2017). Publication of the thesis as a CGES Working Paper was recommended by the Examination Committee as one of the best theses defended by the students of the MA SES in 2018. -

April 11, 2021 Under Attack: Terrorism and International Trade in France

April 11, 2021 Under Attack: Terrorism and International Trade in France, 2014-16* Volker Nitsch Isabelle Rabaud Technische Universität Darmstadt Université d’Orléans, LEO, Abstract Terrorist events typically vary along many dimensions, making it difficult to identify their economic effects. This paper analyzes the impact of terrorism on international trade by examining a series of three large-scale terrorist incidents in France over the period from January 2015 to July 2016. Using firm-level data at monthly frequency, we document an immediate and lasting decline in cross-border trade after a mass terrorist attack. According to our estimates, France’s trade in goods, which accounts for about 70 percent of the country’s trade in goods and services, is reduced by more than 6 billion euros in the first six months after an attack. The reduction in trade mainly takes place along the intensive margin, with particularly strong effects for partner countries with low border barriers to France, for firms with less frequent trade activities and for homogeneous products. A possible explanation for these patterns is an increase in trade costs due to stricter security measures. JEL Classification Codes: F14; F52 Keywords: shock; insecurity; uncertainty; terrorism; international trade; France * We thank Béatrice Boulu-Reshef, Stefan Goldbach, Jérôme Héricourt, Laura Hering, Christophe Hurlin, Miren Lafourcade, Laura Lebastard, Daniel Mirza, Serge Pajak, Felipe Starosta de Waldemar, Patrick Villieu, three anonymous referees, and participants at presentations in Bern (European Trade Study Group), Darmstadt, Köln (Verein für Socialpolitik), Orléans (Association Française de Science Economique), Paris (Université Paris-Saclay, RITM, and Université Paris-Est, ERUDITE), and Poitiers for helpful comments. -

Chapter 11 Prevention of Radicalization in Western Muslim

Chapter 11 Prevention of Radicalization in Western Muslim Diasporas by Nina Käsehage This chapter opens with a brief definition of key terms such as “Muslim diasporas,” “prevention of violent extremism” (PVE), “countering violent extremism” (CVE) and discusses the role of Islamophobia in radicalization and its impacts on the prevention of radicalization. The size of the Muslim population in each of the selected five Western countries and the appearance of jihadist, left- and right-wing-groups, as well as the number of attacks resulting from these milieus are briefly discussed at the beginning of the country reports. The main body of this chapter discusses academic, governmental, and civil society approaches to PVE/CVE. For each country, some PVE examples are presented which might be helpful to policymakers and practitioners. A literature review regarding PVE/CVE approaches in each country seeks to provide an overview of the academic state of the art concerning the prevention of radicalization. Finally, a number of recommendations with regard to future PVE initiatives are provided, based on the author’s field research in Salafi milieus in various European countries.1 Keywords: countering violent extremism (CVE), countering violent extremism policy and practice, extremism, government and civil society responses, Muslim communities, Muslim diasporas, prevention, preventing violent extremism (PVE), PVE recommendations, radicalization, religious extremism, Salafism, terrorism 1 The following chapter includes extracts from the book: Nina Käsehage (2020). ‘Prevention of Violent Extremism in Western Muslim Diasporas’, Religionswissenschaft: Forschung und Wissenschaft. Zürich: LIT Verlag. HANDBOOK OF TERRORISM PREVENTION AND PREPAREDNESS 305 This chapter seeks to describe the state of research on the prevention of radicalization in Western Muslim diasporas. -

The Dynamics of the Contemporary Military Role: in Search of Flexibility1

DOI:10.17951/k.2018.25.2.7 ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS MARIAE CURIE-SKŁODOWSKA LUBLIN – POLONIA VOL. XXV, 2 SECTIO K 2018 Jagiellonian University in Kraków. Faculty of International and Political Studies AGATA MAZURKIEWICZ ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4908-1492 The Dynamics of the Contemporary Military Role: In Search of Flexibility1 ABSTRACT The article offers an overview and reflection on the dynamics of the military role taking into account different security contexts and significant others. It analyses two dominant types of military roles: warrior embedded in the realistic perspective on security and peacekeeper grounded in the liberal approach. Finally, it examines the dynamics of the modern military role in the light of the internal-external security nexus. The article shows that the contemporary military role needs not only to combine warrior and peacekeeper roles but also develop some new elements in order to meet the requirements of the contemporary security context. The article begins by setting a theoretical framework that allows for an analysis of drivers of change of the military role. It then moves towards an examination of the contextual drivers of change which influence the two traditional conceptualisations of military role: a “warrior” and a “peacekeeper”. Next, the article turns towards the topic of internal-external security nexus as characteristic to the contemporary security context. Finally, it considers the contextual drivers of change within two areas of military involvement: domestic counter-terrorism operations and cyber security. The article ends with three main conclusions. Firstly, the contemporary military role requires more adaptability with regard to referent objects. -

National Capital Area

National Capital Area Joint Service Graduation Ceremony For National Capital Consortium Medical Corps, Interns, Residents, and Fellows National Capital Consortium Dental Corps and Pharmacy Residents Health and Business Administration Residents Healthcare Administration Residents Rear Admiral David A. Lane, Medical Corps, U.S. Navy Director National Capital Region Medical Directorate Colonel Michael S. Heimall, Medical Service Corps, U.S. Army Director Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Arthur L. Kellermann, M.D., M.P.H. Professor and Dean, F. Edward Hebert School of Medicine Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Jerri Curtis, M.D. Designated Institutional Official National Capital Consortium Associate Dean for Graduate Medical Education Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Colonel Brian M. Belson, Medical Corps, U.S. Army Director for Education Training and Research Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Colonel Clifton E. Yu, Medical Corps, U.S. Army Director, Graduate Medical Education Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Program of Events Academic Procession Arrival of the Official Party Rendering of Honors (Guests, please stand) Presentation of Colors...............................Uniformed Services University Tri-Service Color Guard “National Anthem”...............................................................................The United States Army Band Invocation.................................................................................LTC B. Vaughn Bridges, CHC, USA -

The Paris Attacks: Charlie Hebdo, November 2015, and Beyond

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2016 The Paris Attacks: Charlie Hebdo, November 2015, and Beyond Hunter R. Pons University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Pons, Hunter R., "The Paris Attacks: Charlie Hebdo, November 2015, and Beyond" (2016). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1932 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Paris Attacks: Charlie Hebdo, November 2015, and Beyond A Chancellor’s Honors Program Senior Thesis Hunter Pons Accounting Spring 2015 “Allahu Akbar” (God is the greatest). These were the words that resonated in the halls of the French satirical weekly newspaper, Charlie Hebdo, on January 7, 2015 around 11:30 local time in Paris. These same words were later heard by hundreds of innocent people again on the evening of Friday 13, November 2015, when terrorists coordinated a series of attacks targeted at mass crowds. Terrorism has never been a top threat to France in the past few decades. However, terrorism will haunt every single French citizen for years to come after witnessing what true terror can cause to a country. -

Lessons-Encountered.Pdf

conflict, and unity of effort and command. essons Encountered: Learning from They stand alongside the lessons of other wars the Long War began as two questions and remind future senior officers that those from General Martin E. Dempsey, 18th who fail to learn from past mistakes are bound Excerpts from LChairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: What to repeat them. were the costs and benefits of the campaigns LESSONS ENCOUNTERED in Iraq and Afghanistan, and what were the LESSONS strategic lessons of these campaigns? The R Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University was tasked to answer these questions. The editors com- The Institute for National Strategic Studies posed a volume that assesses the war and (INSS) conducts research in support of the Henry Kissinger has reminded us that “the study of history offers no manual the Long Learning War from LESSONS ENCOUNTERED ENCOUNTERED analyzes the costs, using the Institute’s con- academic and leader development programs of instruction that can be applied automatically; history teaches by analogy, siderable in-house talent and the dedication at the National Defense University (NDU) in shedding light on the likely consequences of comparable situations.” At the of the NDU Press team. The audience for Washington, DC. It provides strategic sup- strategic level, there are no cookie-cutter lessons that can be pressed onto ev- Learning from the Long War this volume is senior officers, their staffs, and port to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman ery batch of future situational dough. The only safe posture is to know many the students in joint professional military of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and unified com- historical cases and to be constantly reexamining the strategic context, ques- education courses—the future leaders of the batant commands. -

Army Instruction – 10/2001

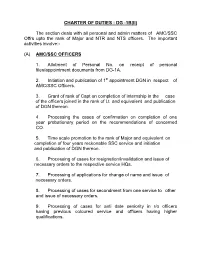

CHARTER OF DUTIES : DG -1B(II) The section deals with all personal and admin matters of AMC/SSC Offrs upto the rank of Major and NTR and NTS officers. The important activities involve:- (A) AMC/SSC OFFICERS 1. Allotment of Personal No. on receipt of personal files/appointment documents from DG-1A. 2. Initiation and publication of 1st appointment DGN in respect of AMC/SSC Officers. 3. Grant of rank of Capt on completion of internship in the case of the officers joined in the rank of Lt and equivalent and publication of DGN thereon. 4. Processing the cases of confirmation on completion of one year probationary period on the recommendations of concerned CO. 5. Time scale promotion to the rank of Major and equivalent on completion of four years reckonable SSC service and initiation and publication of DGN thereon. 6. Processing of cases for resignation/invalidation and issue of necessary orders to the respective service HQs. 7. Processing of applications for change of name and issue of necessary orders. 8. Processing of cases for secondment from one service to other and issue of necessary orders. 9. Processing of cases for anti date seniority in r/o officers having previous coloured service and officers having higher qualifications. -2- 10. Processing of cases for issue of No Objection Certificate to officers applying for civil employment. 11. Grant of extension to officers completing the initial contractual period of five years. 12. Compilation of manpower reports based on authorization and holding returns received from the three service HQs. 13. Compilation and submission of required report and returns to the Coord section, Addl DGAFMS and the DGAFMS. -

The History of the Navy Medical Corps Insignia: a Case for Diagnosis

ment Duty Navy Medical Corps Insignia 615 ing to ANG units. MTFs are sensitive to the charge of exploiting Acknowledgments Reserve Forces to "clean up" their backlog of physicals. In this case, AFSC Hospital, Patrick took the lead by helping an ANG We wish to commend COL Robert F. Thomas, Commander, unit receive pertinent training. ER duty is possible for any ANG AFSC Hospital, Patrick, and TSGT Carey P. Martin, NCOIC of the medical unit, provided that the unit obtains the necessary ba ER at Patrick AFB, who coordinated and evaluated this unique ANG training experience. Their skill and understanding helped to sic skills and certifications prior to the annual training deploy ensure the success of this noteworthy endeavor. We also thank ment. This requires that the unit depart from focusing as much RobertD. Cardwell, Deputy Chief of Staff for Air. MDANG, and COL on purely administrative and non-medical matters during Vernon A. Sevier, Commander of the 135th Tactical Airlift Group, UTAs and concentrate on obtaining, honing, and retaining 2E MDANG. Without their support, this unique training opportunity related medical skills. would not have been possible. MILITARY MEDICINE. 156. !1:615, 1991 The History of the Navy Medical Corps Insignia: td sensi· d super· A Case for Diagnosis m staff . : annual do their LT KennethM. Lankin, MC USN his was ~ecause ow did the oak leaf and the acorn (Fig. 1) become the often jobs in Hunrecognized symbol of the Navy Medical Corps? As LT 12-hour T.W. Ziegler, MC, USNR, wrote to the Chief of the Navy Bureau perma· of Medicine and Surgery (BUMED) in 1968: ed high "Throughout my tour of duty in Vietnam with the joint e taken Army-Navy Mobile Riverine Force .. -

Saving Strangers in Libya: Traditional and Alternative Discourses on Humanitarian Intervention by Sorana-Cristina Jude

Centre International de Formation Européenne Institut Européen ● European Institute Saving Strangers in Libya: Traditional and Alternative Discourses on Humanitarian Intervention By Sorana-Cristina Jude Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Advanced European and International Studies (Anglophone Branch) Supervisor: Tobias Bütow (DAAD Lecturer) Nice, France 2011/2012 Abstract The paper inquires into the 2011 intervention in Libya through the lens of traditional and alternative approaches on International Relations Theory and International Law as means to unveil the academic-informed discourses that justify the latest military action in the Mediterranean region. Claiming that the intervention in Libya is justified by a blending between an international discourse of responsibility with a utilitarian approach on humanitarian intervention, the paper reflects upon the politicization of humanitarian intervention in current international affairs. In order to support this argument, the paper forwards Realist, Constructivist and respectively, Poststructuralist appraisals of the humanitarian intervention in Libya in order to bring to light the subject matter. i Acknowledgements I am indebted to Mr. Tobias Bütow for his patience, academic encouragement and moral support that guided me during this program. His belief in the potential of this paper provided me with the necessary impetus to overcome the difficult moments in writing it. Special gratitude goes towards my parents, brother, sister-in-law, nephews for their love and for teaching me to aspire to the heights. Their high yet reasonable expectations from me are the driving force behind my accomplishments. My friends provided me with necessary moments of laughter during both difficult times and joyful moments.