84. Ropley in the Age of Smuggling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Hampshire District Council Bordon Sandpit, Hanson Heidelberg - EH Picketts Hill, 480700 138510 Yes Operating Under District Permission

Site Code LPA Site Name Grid Ref Operator / Agent Safeguarded site Site Narrative - East Hampshire District Council Bordon Sandpit, Hanson Heidelberg - EH Picketts Hill, 480700 138510 Yes Operating under district permission. Not monitored Cement Group Sleaford, Bordon John Huntley - EH Buriton 473224 121048 Yes No planning history (Petersfield) Ltd. Mineral Safeguarding - EH - - Yes Proposed in the HMWP 2013 Area - Whitehill & Bordon Waterbook Road, - EH 472974 139618 Kendall Group Yes Operating under district permission. Not monitored Mill Lane, Alton Sleaford Closed Landfill Site, EH012 EH (Former 479940 138397 Robert Long Consultancy No Former landfill site, now restored. Permission to recontour the site and improve surface drainage not implemented. Coldharbour Landfill Site) Ceased Non-inert landfill, restoration completed May 2019 (27242/014) || Active landfill gas generation; extension to existing leachate treatment plant, installation of inflow balance tank, update SCADA system, chemical and nutrient dosing plant, new pH and DO sensors, sludge extraction Southleigh Forest, Veolia Environmental system, modifications to pipework, caustic soda tank (until 31 December 2020) (06/67492/002) || Temporary erection of a 50 metre full anemometry EH018 EH 473903 108476 No Rowlands Castle Services (UK) Plc mast with four sets of guy cables, anchored 25m from the base to record wind data for a temporary period (F/27242/011/CMA) granted 07/2008; (Woodland and amenity - 2014) || Liaison Panel (0 meetings) main issues: panel mothballed until nearer -

Notification of All Planning Decisions Issued for the Period 11 June 2021 to 17 June 2021

NOTIFICATION OF ALL PLANNING DECISIONS ISSUED FOR THE PERIOD 11 JUNE 2021 TO 17 JUNE 2021 Reference No: 26982/011 PARISH: Horndean Location: Yew Tree Cottage, Eastland Gate, Lovedean, Waterlooville, PO8 0SR Proposal: Installation of access gates with brick piers, resurfacing of hardstanding and installation of training mirrors along east side of manege (land adj to Yew Tree Cottage) Decision: REFUSAL Decision Date: 16 June, 2021 Reference No: 59273 PARISH: Horndean Location: 31 Merchistoun Road, Horndean, Waterlooville, PO8 9NA Proposal: Prior notification for single storey development extending 4 metres beyond the rear wall of the original dwelling, incorporating an eaves height of 3 metres and a maximum height of 3 metres Decision: Gen Permitted Development Conditional Decision Date: 17 June, 2021 Reference No: 37123/005 PARISH: Horndean Location: Church House, 329 Catherington Lane, Horndean Waterlooville PO8 0TE Proposal: Change of use of existing outbuilding to holiday let and associated works (as amended by plans received 20 May 2021). Decision: PERMISSION Decision Date: 11 June, 2021 Reference No: 50186/002 PARISH: Horndean Location: 38 London Road, Horndean, Waterlooville, PO8 0BX Proposal: Retrospective application for entrance gates and intercom Decision: REFUSAL Decision Date: 15 June, 2021 Reference No: 59252 PARISH: Rowlands Castle Location: 18 Nightingale Close, Rowlands Castle, PO9 6EU Proposal: T1-Oak-Crown height reduction by 3m, leaving a crown height of 13m. Crown width reduction by 2.5m, leaving a crown width of 4.5m. Decision: CONSENT Decision Date: 17 June, 2021 Reference No: 25611/005 PARISH: Rowlands Castle Location: 5 Wellswood Gardens, Rowlands Castle, PO9 6DN Proposal: First floor side extension over garage, replacement of bay window with door and internal works. -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

Winchester Museums Service Historic Resources Centre

GB 1869 AA2/110 Winchester Museums Service Historic Resources Centre This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 41727 The National Archives ppl-6 of the following report is a list of the archaeological sites in Hampshire which John Peere Williams-Freeman helped to excavate. There are notes, correspondence and plans relating to each site. p7 summarises Williams-Freeman's other papers held by the Winchester Museums Service. William Freeman Index of Archaeology in Hampshire. Abbots Ann, Roman Villa, Hampshire 23 SW Aldershot, Earthwork - Bats Hogsty, Hampshire 20 SE Aldershot, Iron Age Hill Fort - Ceasar's Camp, Hampshire 20 SE Alton, Underground Passage' - Theddon Grange, Hampshire 35 NW Alverstoke, Mound Cemetery etc, Hampshire 83 SW Ampfield, Misc finds, Hampshire 49 SW Ampress,Promy fort, Hampshire 80 SW Andover, Iron Age Hill Fort - Bagsbury or Balksbury, Hampshire 23 SE Andover, Skeleton, Hampshire 24 NW Andover, Dug-out canoe or trough, Hampshire 22 NE Appleshaw, Flint implement from gravel pit, Hampshire 15 SW Ashley, Ring-motte and Castle, Hampshire 40 SW Ashley, Earthwork, Roman Building etc, Hampshire 40 SW Avington, Cross-dyke and 'Ring' - Chesford Head, Hampshire 50 NE Barton Stacey, Linear Earthwork - The Andyke, Hampshire 24 SE Basing, Park Pale - Pyotts Hill, Hampshire 19 SW Basing, Motte and Bailey - Oliver's Battery, Hampshire 19 NW Bitterne (Clausentum), Roman site, Hampshire 65 NE Basing, Motte and Bailey, Hampshire 19 NW Basingstoke, Iron -

26 July 2021

Town and Country Planning Acts 1990 Planning (Listed Building and Conservation Area) Act 1990 LIST OF NEW PLANNING AND OTHER APPLICATIONS DECIDED IN PARISH ORDER DECISION LIST AS OF 26 July 2021 The following is a list of applications which have been decided in the week shown above. These will have been determined, under an agency agreement, by East Hants District Council, unless the application was ‘called in’ by the South Downs National Park Authority for determination. Further details regarding the agency agreement can be found on the SDNPA website at www.southdowns.gov.uk. If you require any further information please contact East Hants District Council. IMPORTANT NOTE: The South Downs National Park Authority has adopted the Community Infrastructure Levy Charging Schedule, which will take effect from 01 April 2017. Applications determined after 01 April will be subject to the rates set out in the Charging Schedule (https://www.southdowns.gov.uk/planning/planning-policy/community-infrastructure- levy/). If you have any questions, please contact [email protected] or tel: 01730 814810. Want to know what’s happening in the South Downs National Park? Sign up to our monthly newsletter to get the latest news and views delivered to your inbox www.southdowns.gov.uk/join-the-newsletter WLDEC East Hampshire District Council Team: East Hants DM team Parish: Chawton Parish Council Ward: Four Marks & Medstead Ward Case No: SDNP/21/03544/APNB Type: Agricultural Prior Notification Building Date Valid: 2 July 2021 Decision: Raise No Objection Decision Date: 23 July 2021 Case Officer: Susie Ralston Method: LA Delegated Decision Applicant: Mr Neil Wallsgrove Proposal: Application to determine if prior approval is required for proposed Erection of a Building for Agricultural use for 3 Polythene Tunnels. -

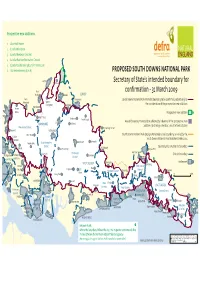

A3 Illustrative Minded to Boundary Plus Local Authorities.Ai

Prospective new additions: 1. Alice Holt Forest 2. Land at Plumpton 3. Land at Roedean Crescent 4. Land at Patcham Recreation Ground 5. Land at Castle Goring/East of Titnore Lane 6. A27 embankments (A to B) PROPOSED SOUTH DOWNS NATIONAL PARK 1 ALTON Binsted Secretary of State's intended boundary for Four confirmation - 31 March 2009 Marks Bordon SURREY New Haslemere South Downs National Park intended boundary to be confirmed, subject only to Alresford Upper Farringdon Liphook the consideration of the prospective new additions Monkwood Itchen Abbas Prospective new addition 2 WINCHESTER West Tisted Fernhurst Northchapel Area of boundary that could be affected by a deletion if the prospective new Liss Milland HAMPSHIRE addition 5 did not go ahead as a result of consultation Winchester District Wisborough Green Twyford PETERSFIELD West Meon South Downs National Park (Designation) Order 2002 boundary, as varied by the Colden Common South Downs National Park (Variation) Order 2004 Petworth Meonstoke East Hampshire MIDHURST Eastleigh District County/Unitary Authority boundary Upham South Harting Pulborough Burgess Hill Chichester Hurstpierpoint Bishop’s Clanfield District boundary Bishopstoke District Duncton Hassocks Eastleigh Waltham 2 Storrington Settlement District WEST SUSSEX Ditchling Shirrell Mid Sussex Singleton East Bury Heath Horsham District Steyning District Ringmer Dean 0 10km SOUTHAMPTON Wickham Stoughton Fulking LEWES B HORNDEAN Lavant Arun Findon 4 Arundel EAST SUSSEX District Adur District Fareham Havant Brighton & Lewes District -

Minutes of the East Tisted Parish Council Meeting

East Tisted Parish Council _____________________________________________________________________ Minutes of the Parish Council Meeting held on Wednesday 29th November 2017 at 6.30pm in East Tisted Village Hall, Gosport Road GU34 3QW Summoned to attend: David Bowtell (Councillor) Phil Cutts (Councillor) Helen Evison (Councillor, RFO & Clerk) Sir James Scott (Chairman) Sandra Nichols (Councillor) Also present: Larry Johnson (Neighbourhood Watch, East Tisted Community Website & Village Hall) Ian Dugdale (Hampshire Constabulary) – until 6.45pm James Merrell (Hampshire Constabulary) – until 6.45pm Charles Louisson (District Councillor) Apologies: Russell Oppenheimer (County Councillor) Matthew Sheppard (Hampshire Constabulary) The meeting opened at 6.30pm 1. Apologies and welcome The Chairman welcomed all. Apologies were received from Russell Oppenheimer and Matthew Sheppard. 2. Declaration of interests None. 3. Public forum a. The meeting received the written report from County Councillor RO, Attachment 1. b. CL advised that: - The District Council Boundary Review was out for consultation and would be closing on 11th December. The aim was to balance the numbers in the various areas and reduce the number of District Councillors by one. It was proposed to enlarge ‘Ropley and Tisted’ to include Colemore, Priors Dean and Hawkley, the new area to be known as ‘Ropley, Hawkley and Hangars’. Parish Councillors agreed that this was a reasonable proposal. - There were no planning issues. - The South Downs Local Plan consultation had closed on 21st November. c. ID and JM reported that the theft of a quad bike was being investigated as were some minor incidents relating to hare coursing and poaching. 6.45pm ID and JM left the meeting d. LJ gave three reports: - Neighbourhood Watch LJ had attended the public meeting in Petersfield; there was a new contact for fly-tipping; various posters were available. -

Ropley Neighbourhood Plan

Ropley Neighbourhood Plan Regulation 15 Submission Version 7 December 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 5 1.0 PLAN SUMMARY 6 2.0 INTRODUCTION 9 3.0 HOW THE ROPLEY NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN WAS PREPARED 10 4.0 A PROFILE OF ROPLEY 12 5.0 PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT 14 6.0 VISION 17 7.0 OBJECTIVES AND POLICIES 18 RNP1: SETTLEMENT AND COALESCENCE GAPS 20 RNP2: SETTLEMENT POLICY BOUNDARIES 24 RNP3: VISTAS AND VISUAL PROMINENCE 27 RNP4: TREES, HEDGEROWS, VERGES AND BANKS 30 RNP5: NARROW LANES 31 RNP6: SUNKEN LANES 32 RNP7: CONSTRUCTION TRAFFIC 35 RNP8: LOCAL GREEN SPACES 36 RNP9: BUILT HERITAGE 41 RNP10: NATURE CONSERVATION 44 RNP11: RIGHTS OF WAY 47 RNP12: IMPACT OF NEW DEVELOPMENT 50 RNP13: DESIGN AND HEIGHT OF NEW HOUSING 51 RNP14: EXTERNAL MATERIALS 53 Page 2 RNP15: DRIVEWAYS AND PARKING 54 RNP16: EXTENSIONS AND NEW OUTBUILDINGS 54 RNP17: ENSURING APPROPRIATE DESIGN AND MATERIALS 55 RNP18: AMOUNT OF NEW HOUSING 58 RNP19: PROPOSED HOUSING SITE OFF HALE CLOSE 62 RNP 20: PROPOSED HOUSING SITE ON THE CHEQUERS INN SITE 65 RNP21: PROPOSED HOUSING SITE ON PETERSFIELD ROAD 67 RNP22: OCCUPANCY RESTRICTION 68 RNP23: PROTECTING COMMUNITY FACILITIES 70 RNP24: NEW COMMUNITY LAND 72 8.0 IMPLEMENTATION AND MONITORING 74 9.0 APPENDIX 1: HOUSING NEEDS ASSESSMENT 76 10.0 APPENDIX 2: HOUSING SITE SELECTION 80 11.0 APPENDIX 3: LIST OF HERITAGE ASSETS 83 12.0 APPENDIX 4: POSSIBLE FUTURE PLAN ITEMS 84 13.0 APPENDIX 5: SCHEDULE OF EVIDENCE 85 14.0 GLOSSARY OF TERMS 90 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 98 Page 3 Page 4 FOREWORD In early 2015, local residents decided to prepare a Neighbourhood Plan for the Parish of Ropley. -

Clay Plateau

C1 Landscape Character Areas C1 : Froxfield Clay Plateau C: Clay Plateau C1 Historic Landscape Character Fieldscapes Woodland Unenclosed Valley Floor Designed Landscapes Water 0101- Fieldscapes Assarts 0201- Pre 1800 Woodland 04- Unenclosed 06- Valley Floor 09- Designed Landscapes 12- Water 0102- Early Enclosures 0202- Post 1800 Woodland Settlement Coastal Military Recreation 0103- Recent Enclosures Horticulture 0501- Pre 1800 Settlement 07- Coastal 10- Military 13- Recreation 0104- Modern Fields 03- Horticulture 0502- Post 1800 Expansion Industry Communications Settlement 08- Industry 11- Communications C: Clay Plateau LANDSCAPE TYPE C: CLAY PLATEAU C.1 The Clay Plateau comprises an elevated block of clay-capped chalk in the western part of the South Downs between Chawton in the north and Froxfield in the south. The boundaries of this landscape type are defined by the extent of the virtually continuous drift deposit of clay with flints that caps the chalk. Integrated Key Characteristics: • Chalk overlain by shallow continuous clay capping resulting in poorer heavier soils. • Large tracts of elevated gently undulating countryside. • A predominantly pastoral farmland landscape with significant blocks of woodland. • Varying enclosure - open and exposed in higher plateau areas with occasional long views, with a more enclosed landscape in relation to woodland cover. • Survival of original pre 1800 woodland and presence of oak as a key species in hedgerows and woodland. • Varied field pattern including irregular blocks of fields are evidence of 15th –17th century enclosure and a more regular field system represents 18th and 19th century enclosure. • Limited settlement comprising dispersed farmsteads and occasional small nucleated villages/hamlets with church spires forming distinctive landscape features. -

East Hampshire Wooded Downland Plateau

6A: EAST HAMPSHIRE WOODED DOWNLAND PLATEAU There is more grazing and permanent grassland in this landscape compared with the rest of the Downs – Bradley Long distance views glimpsed through Dry Valley or Coombe at Bentworth. Wooded Dowland Plateau at woodland from Wooded Downland Colemore Common – elevated and Plateau near High Cross heavily wooded. Brick and flint school at Bentworth Bentworth parish church. There are Sunken lane at edge of Downland several substantial churches, like this Plateau east of Axford. in small villages. Hampshire County 1 Status: FINAL May 2012 Integrated Character Assessment East Hampshire Wooded Downland Plateau Hampshire County 2 Status: FINAL May 2012 Integrated Character Assessment East Hampshire Wooded Downland Plateau 1.0 Location and Boundaries 1.1 The East Hampshire Wooded Downland Plateau is an elongated area located towards the eastern edge of the Hampshire Downs, stretching from close to Alton in the north, to the top of the chalk escarpment north west of Petersfield. The boundaries of this high, gently undulating plateau are closely related to the extent of a deep clay cap over the chalk. 1.2 Component County Landscape Types Wooded Downland Plateau, Downland Mosaic Large Scale. 1.3 Composition of Borough/District LCAs: East Hampshire District Council Froxfield Clay Plateau Four Marks Clay Plateau Very closely associated with the above - combined but boundary taken at top of perimeter slopes rather than at base. 1.4 Associations with NCAs and Natural Areas: NCA 130: Hampshire Downs and JCA 125: South Downs Natural Areas: 78 Hampshire Downs 2.0 Key Characteristics • An elevated plateau landscape, mainly fairly flat but with dry chalk valleys, creating gentle undulations, capped with a deep layer of clay. -

Shawford. 3 Miles. Long, J., Farmer, Monkwood (Post Town-Winchester.) Looker, J ., Garage, Soke Hill Abraham, G

1913] ROPLEY DIRECTORY. 381 Dibben, , Red barn Miller, G., proprietor steam ploughs Dunn, S. (second whip H.H.) Munday, G., farmer, Kitfield Dunford, L., Hampshire Cottage Nash, F., Alton lane Ford Bros., cycle agents, Church-st. N orris, Mrs., Laurel Cottage Ford, Walter, painter, registrar of Norgate, T., thatcher, Ham's lane births, &c. Oakes, B., Hilden Paddocks Gaiger, G. (feeder, H.H.) Orvis, W., (first whip H.H.) Gardner, A., Blackberry lane Panter, S., Stapley road [office Gardner, C., gardener, South-st. Parsons, M. A., Four Marks post Goodall, J., coal agetth_Bopley Dene Parmiter, W. E., grocer, Church-st. Green, A. E., sanitary inspector Privett, A., carpenter and builder Gunn,E.,Prudential Insurance agent, Privett, Mrs., Hammonds lane Ropley Dene Read, Mrs., farmer, South-st. Guy, A., South-st. Reed, F., fanner, Charlwood Hale, A. H., newsagent, Holmfield Reffell, W. H., Blackberry lane Hale, George, blacksmith, machinist Rendell, A., Monkwood and farmer Run yard, G. R., blacksmith, South-st. Hale, James, wheelwright, Star inn Savage, , constable Hall, James B., builder and carpenter, Simpson, J., Hawthorne Ham's lane Smith, H., the Shant · Hall, Miss, Stapley lane Spackman, T., Blackberry lane Hannam, A. H., Alberta cottage Stenning, T., Chapel lane Harding Bros., grocers and bakers, Tancock, J ., farmer, Church.st. Gilbert-st. Thomlinson, H., nurseries Harding, W., farmer, Chase's farm Tollafield, J., Lymington Harris & Son, threshers, the Dene Tomlinson, Mrs., the Homestead, Harrison, F., station mC).Ster Four Marks Harvey, H. A., Gilbert street Tomlinson, T. W., Four Marks Hawes, H. F., Anchor Inn The Coffee Room & Men's Club open Heale, G., Alton lane to working men every night from Heath, F. -

Town and Country Planning Acts 1990 Planning (Listed Building and Conservation Area) Act 1990

Town and Country Planning Acts 1990 Planning (Listed Building and Conservation Area) Act 1990 LIST OF NEW PLANNING AND OTHER APPLICATIONS, RECEIVED AND VALID WEEKLY LIST AS AT 28 June 2021 The following is a list of applications which have been received and made valid in the week shown above. These will be determined, under an agency agreement, by East Hants District Council, unless the application is ‘called in’ by the South Downs National Park Authority for determination. Further details regarding the agency agreement can be found on the SDNPA website at www.southdowns.gov.uk. If you require any further information please contact East Hants District Council who will be dealing with the application. IMPORTANT NOTE: The South Downs National Park Authority has adopted the Community Infrastructure Levy Charging Schedule, which will take effect from 01 April 2017. Applications determined after 01 April will be subject to the rates set out in the Charging Schedule (https://www.southdowns.gov.uk/planning/planning-policy/community-infrastructure-levy/). If you have any questions, please contact [email protected] or tel: 01730 814810. Want to know what’s happening in the South Downs National Park? Sign up to our monthly newsletter to get the latest news and views delivered to your inbox www.southdowns.gov.uk/join-the-newsletter WLVAL East Hampshire District Council Team: East Hants DM team Parish: Buriton Parish Council Ward: Buriton & East Meon Ward Case No: SDNP/21/02979/HOUS Type: Householder Date Valid: 24 June 2021 Decision due: 19 August 2021 Case Officer: Rosie Virgo Applicant: Emma Fitzmaurice-Kemp Proposal: Front and rear dormers to existing loft conversion.