Iowa Indians' Political and Economic Adaptations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Otoe-Missouria Tribal Newsletter

VOLUME 12 • NUMBER 1 • COVID 19 EDITION THE OTOE-MISSOURIA TRIBAL NEWSLETTER Shuttered Businesses Mean Less Funding for Assistance; Per Capita Payments By Courtney Burgess, are all funded by revenue from April 1st. The Otoe-Missouria Tribal Treasurer our tribal businesses. Tribe is fortunate enough to I hope you and your families Additionally, many of our be able to provide this aid dur- are staying safe and doing well programs are supplemented ing this time. during this challenging time. by the revenue in our Gen- Per Capita payments are Dear Otoe-Missouria It has been hard for all of us, eral Fund to help meet short- also stimulated by the revenue and even harder for some of falls that the program’s grant from our casinos. With the ca- Tribal Members, us who have been affected by doesn’t cover or as a required sinos being closed, per capita I hope that this correspon- COVID-19. match to the grant. payments may not be as high dence finds you and your loved The Tribal Council has taken A significant portion of our as you normally receive. How- have been working very hard ones in good health. Like the all precautions to keep tribal General Fund goes to fund ever, this all depends on when to keep our children’s money rest of the world, we have deal- members, children, employees our Tribal Assistance Program we reopen our casinos. safe. ing with the effects of the Co- and visitors safe. The Tribal (TAP). TAP is funded EN- The minor’s per capita in- We are currently practicing vid-19 Virus. -

Iowa City, Iowa - Tuesday, June 6, 2006 NEWS

THE INDEPENDENT DAILY NEWSPAPER FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA COMMUNITY SINCE 1868 The Daily Iowan TUESDAY, JUNE 6, 2006 WWW.DAILYIOWAN.COM 50¢ LAVALLEE’S CRÊPES Hoping to govern WHERE TO VOTE CANDIDATES Polls for today’s primary elections will open at 7 a.m. and close at 9 p.m. To be eligible, voters must be affiliated with either the Democratic or Republican Parties or register with either at their polling places, which can be found by accessing http://www.johnson-county.com/audi- tor/lst_precinctPublicEntry.cfm. Voters are eligible to vote only for candidates from their registered party. Today’s winners will repre- sent their respective parties in the Nov. 7 general election. MIKE BLOUIN CHET CULVER ED FALLON Blouin graduated from Culver, the son of Fallon graduated from Dubuque’s Loras College former U.S. Sen. John Drake University with a with a degree in political Culver, graduated from degree in religion in science in 1966. After a Virginia Tech University 1986. He was elected to stint as a teacher in with a B.A. in political the Iowa House of Dubuque, he was elected science in 1988 and a Representatives in to the Iowa Legislature at master’s from Drake in 1992, and he is age 22, followed by two 1994 before teaching currently serving his terms in the U.S. House. high school in Des seventh-consecutive BACKGROUND He later worked in the Moines for four years. term. Fallon is the Carter administration, and Culver was elected executive director and he most recently served Iowa’s secretary of co-founder of 1,000 as the director of the State in 1998; his Friends of Iowa, an Iowa Department of second term will expire organization promoting Economic Development. -

A Statistical Study of the Variations in Des Moines River Water Quality Lewis Metzler Naylor Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1975 A statistical study of the variations in Des Moines River water quality Lewis Metzler Naylor Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Civil Engineering Commons, and the Oil, Gas, and Energy Commons Recommended Citation Naylor, Lewis Metzler, "A statistical study of the variations in Des Moines River water quality " (1975). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5496. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5496 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Otoe-Missouria Tribe Internet Commerce: Helping Our People

OTOE-MISSOURIA TRIBE INTERNET COMMERCE: HELPING OUR PEOPLE BACKGROUND The Otoe-Missouria Tribe is a Red Rock, Oklahoma-based Native American tribe with nearly 3,000 members. The Otoe-Missouria faces the unfortunate and all-too-common struggles plaguing Indian country today: staggering unemployment rates, limited opportunities, and lack of access to fundamental resources. In an increasingly competitive gaming environment, in which the Tribe has witnessed competitors open casinos in painful proximities, we continue to feel the seemingly insurmountable pressures of finding ways to relieve our gaming operations of the disproportionate burden of providing for our members. INTERNET COMMERCE INITIATIVES: PROVIDING FOR OUR PEOPLE In 2009, the Otoe-Missouria Tribe took a giant leap in developing economic opportunities for the Tribe and its members: establishing itself in the internet commerce arena. Internet commerce has been an invaluable vehicle for economic growth, tribal services, and tribal development. Internet commerce’s potential impact on tribal growth and opportunity is immeasurable. Its effects have already proven tremendously critical for tribal advancement and financial assistance: Budget: Accounts for 25% of Otoe-Missouria’s Non-federal Tribal budget; Employment: Created 65 jobs on Tribal land, including financial support staff, Head Start educators, and Tribal housing personnel; Infrastructure: Critical funding for new tribal housing and renovation; Education: Additional classrooms, books, and teachers for Head Start, New after-achool program, New Summer Youth program; Tribal Services: Child Care Services, employment training, natural resources development, financial assistance, utility assistance, healthcare and wellness coverage, emergency assistance; Social Services: Child protection, Low- income Home Energy Assistance Program,family violence protection. -

WONDERFUL OTOE INDIAN COLLECTION Presented to Nebraska State Historical Society by Major A

NEBRASKA HISTORY MAGAZINE 169 These houses are mostly rectangular, some however are round. They are from 18 to 55 feet in diameter and the floor level varies from seven inches to forty-two inch es below the present surface. Much valuable and inter esting information and evidence has been obtained but further work is necessary for proof of conclusions which are now assumed. In the vicinity of these sites are other sites in which no work has been done. It is very important that this work be carried forward as soon as possible as valuable eyidence is rapidly disappearing by erosion, decomposi tion, tillage of the soil and in several instances by inex perienced people digging into them. The Campaign of 1934 in prehistoric Nebraska will begin in May. Director Hill will take the field with a trained corps of workers. Camping outfits will locate at some of the sites which have been selected. Scientific equipment and methods will be employed. New and im portant chapters in the story of prehistoric peoples in Nebraska will be made known in this campaign. And the evidences of the buried aboriginal empire on these plains will be assembled in the Nebraska Historical Soci ety Museum in the State Capitol. -----0---- WONDERFUL OTOE INDIAN COLLECTION Presented to Nebraska State Historical Society by Major A. L. Green, of Beatrice and His Son T. L. Green, of Scottsbluff. Otoe Land was Southeastern Nebraska from the Platte River south to the Big Nemaha, from the Missouri west to the Big Blue. The capitol city of this Otoe Em pire was the great Otoe village, about three miles south east of the present village of Yutan in Saunders county. -

April 22—23, 2016 Grand View University

PROCEEDINGS OF THE 128TH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE IOWA ACADEMY OF SCIENCE April 22—23, 2016 Grand View University FRIDAY SCHEDULE Time Events Location Page 7:30 a.m. IJAS Registration SC Lobby 2, 3 7:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. IAS Bookstore Open SC Lobby 2, 3 8:00 a.m. Registration Desk Opens SC Lobby 2, 3 8:00 a.m. Silent Auction begins SC Lobby 2, 3 8:00 a.m. -10:30 a.m. Morning Snack SC Lounge 2 8:00 a.m. - 3:00 p.m. IJAS Program Schedule 10 8:00 a.m. -10:45 a.m. IJAS Poster Presentations SC Lounge 7-9 SC—See IJAS Schedule 8:00 a.m. - 10:45 a.m. IJAS Oral Presentations 10 11:00 a.m. - Noon General Session I SC Speed Lyceum 12 Noon - 1:15 p.m. IJAS Award Luncheon Valhallah Dining 11,12 1:15 p.m. -1:40 p.m. IAS Business Meeting SC Plaza View Room 12 Exploring Lunar & Planetary SC Conference A & B 1:30 p.m. -2:25 p.m. 10 Science with NASA IJAS Grand View University 1:30 p.m. - 4:00 p.m. SC Conference A,B,C 10 Event 1:45 p.m. - 4:30 p.m. Symposiums A, B, C See Symposiums Schedule 13, 14 4:30 p.m. - 5:45 p.m . Senior Poster Session SC Lounge 14 4:45 p.m. - 6:00 p.m. Social Hour SC Lounge 14 6:00 p.m. -7:30 p.m. President’s Banquet Valhallah Dining 15 7:45 p.m. -

The Otoe-Missouria Flag Song

Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics, Vol. 30 (2008), p. 98 The Otoe-Missouria Flag Song Jill D. Greer Social Science Department, Missouri Southern State University Introduction As the title suggests, the focus of this paper is upon a single important song within the Otoe- Missouria tribe. This is a preliminary sketch, or a truly working paper as the KU publication series denotes. In subject and approach, it has been inspired by the venerable tradition of collecting, preserving, and analyzing Native American texts begun with 19th century BAE ethnographers such as James Owen Dorsey, encouraged by Franz Boas and his Americanist students, and celebrated by more recent scholars of verbal art as Hymes, Tedlock, Sherzer, and Basso. The particular esthetic principles used in the text will link it clearly to other tribal songs, and to the performance context as well. I will also raise issues of cultural change and continuity in the context of language shift, and finally, I argue that this Flag Song compellingly demonstrates the value of maintaining a heritage language within endangered and obsolescent language communities.1 By a heritage language, I mean a language which may no longer exist as an “everyday spoken medium of communication” but which may persist in special settings, such as the realm of sacred language in songs and prayer.2 The Western tradition has the familiar example of Latin preserved by use in the Church and as the common written language of scholars, but unlike Latin, the majority of Native languages were not represented in written form by their respective speech communities.3 The numerous circumstances leading to language shift within the Otoe- Missouria community have been similar to that documented elsewhere for the First Nations peoples in the U.S., and it is beyond the scope of this paper to review that tragic process in detail. -

Mid-Term Report Format and Requirements

Final Report Form REAP Conservation Education Program Please submit this completed form electronically as a Word document to Susan Salterberg [email protected] (CEP contract monitor). Project number (example: 12-04): 13-14 Project title: Investigating Shelter, Investigating a Midwestern Wickiup Organization’s name: University of Iowa Office of the State Archaeologist Grant project contact: Amy Pegump Report prepared by: Lynn M. Alex Today’s date: March 17, 2014 Were there changes in the direction of your project (i.e., something different than outlined in your grant proposal)? Yes No If yes, please explain the changes and the reason for them: No major changes in the direction of the project, although an extension was received to complete one final task. Slight change to line item categories on the budget, but approval was received in advance for these. Note: Any major changes must be approved by the Board as soon as possible. Contact CEP Contract Monitor, Susan Salterberg, at [email protected] or 319-337-4816 to determine whether board approval is needed for your changes. When the REAP CEP Board reports to the Legislature on the impact of REAP CEP funds on environmental education in Iowa, what one sentence best portrays your project’s impact? Response limited to 375 characters. Character limits include spaces. This upper elementary curriculum provides authentic, inquiry-based lessons for educators and their students to learn more about Iowa's early environments, natural resources, and the interrelationship with early human residents and lifeways. Please summarize your project below in the space provided. Your honesty and frankness is appreciated, and will help strengthen environmental education in Iowa. -

Time for a Field Trip!

Field Trip Curriculum for 4th-6th Grade Students Time for a Field Trip! Pre-Field Trip Warm Up____________________ Starved Rock and Matthiessen State Parks IDNR Educational Trunks: People and Animals from Illinois’ Past https://www2.illinois.gov/dnr/education/Pages/ ItemsForLoan.aspx Group Permit Form (to be completed prior to visit) https://www2.illinois.gov/dnr/Parks/Activity/Pages/ StarvedRock.aspx Enjoy Your Trip! Starved Rock Wigwam STEAM Activity- Pages 2 & 3 “Starved Rock History and Activity Packet - Pages 4-10 Thank you for your Day of Field Trip Activities________________________ interest in Starved 1.5 –2 hours Rock State Park. The Field Trip Pack for Teachers following is a packet of https://www2.illinois.gov/dnr/education/Pages/ materials intended to assist teachers in using ItemsForLoan.aspx the site for field trips. Hike to Starved Rock and French Canyon .8 miles roundtrip For your convenience, Map: https://www2.illinois.gov/dnr/Parks/Pages/ we have assembled a StarvedRock.aspx list of activities that Scavenger Hunt - Page 11 can be incorporated Tour the Visitor Center exhibits into the classroom and In the Shadow of the Rock film—15 minutes daily lesson plans in conjunction with a POST-VISIT ACTIVITIES field trip to Starved Rock State Park. • Write your own Starved Rock Story: “My Day at Starved Rock State Park” Template Page 12 2 2 Wigwam Construction: Engineering 3 The Kaskaskia People lived in villages of small round houses called wigwams. What you need: 6 for each student or pair of (buddy up) Square pieces of cardboard box for each student/pair Circle to trace/tree bark sheets Instructions: Have students trace the circle template onto their square piece of cardboard. -

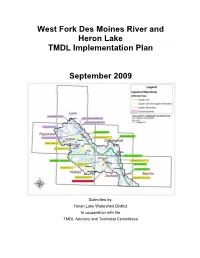

West Fork Des Moines River and Heron Lake TMDL Implementation Plan

West Fork Des Moines River and Heron Lake TMDL Implementation Plan September 2009 Submitted by: Heron Lake Watershed District In cooperation with the TMDL Advisory and Technical Committees Preface This implementation plan was written by the Heron Lake Watershed District (HLWD), with the assistance of the Advisory Committee, and Technical Committee, and guidance from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) based on the report West Fork Des Moines River Watershed Total Maximum Daily Load Final Report: Excess Nutrients (North and South Heron Lake), Turbidity, and Fecal Coliform Bacteria Impairments. Advisory Committee and Technical Committee members that helped develop this plan are: Advisory Committee Karen Johansen City of Currie Jeff Like Taylor Co-op Clark Lingbeek Pheasants Forever Don Louwagie Minnesota Soybean Growers Rich Perrine Martin County SWCD Randy Schmitz City of Brewster Michael Hanson Cottonwood County Tom Kresko Minnesota Department of Natural Resources - Windom Technical Committee Kelli Daberkow Minnesota Pollution Control Agency Jan Voit Heron Lake Watershed District Ross Behrends Heron Lake Watershed District Melanie Raine Heron Lake Watershed District Wayne Smith Nobles County Gordon Olson Jackson County Chris Hansen Murray County Pam Flitter Martin County Roger Schroeder Lyon County Kyle Krier Pipestone County and Soil and Water Conservation District Ed Lenz Nobles Soil and Water Conservation District Brian Nyborg Jackson Soil and Water Conservation District Howard Konkol Murray Soil and Water Conservation District Kay Clark Cottonwood Soil and Water Conservation District Rose Anderson Lyon Soil and Water Conservation District Kathy Smith Martin Soil and Water Conservation District Steve Beckel City of Jackson Mike Haugen City of Windom Jason Rossow City of Lakefield Kevin Nelson City of Okabena Dwayne Haffield City of Worthington Bob Krebs Swift Brands, Inc. -

Researching Native Americans at the National Archives in Atlanta

Researching Individual Native Americans at the National Archives at Atlanta National Archives at Atlanta 5780 Jonesboro Road Morrow, GA 30260 770-968-2100 www.archives.gov/southeast E-Mail: [email protected] Spring, 2009 Researching Individual Native Americans at the National Archives at Atlanta Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Tribal Association ............................................................................................................................ 1 Race .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Tribal Membership ........................................................................................................................... 2 Textual Records ............................................................................................................................... 2 Native American Genealogy ............................................................................................................ 3 Published Resources ......................................................................................................................... 3 Online Resources ............................................................................................................................. 4 Dawes Commission .................................................................................................................................. -

Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments

Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments by Thomas J. Sloan, Ph.D. Kansas State Representative Contents Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments ....................................... 1 The Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas ..................... ................................................................................................................... 11 Prairie Band of Potawatomi ........................... .................................................................................................................. 15 Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska .............................................................................................................................. 17 Appendix: Constitution and By-Laws of the Kickapoo Tribe of Indians of the Kickapoo Reservation in Kansas ..................................... .................. ............................................................................................... 19 iii Tribal Governments in Kansas and Their Relations with State and Local Governments Overview of American Indian Law cal "trust" relationships. At the time of this writing, and Tribal/Federal Relations tribes from across the United States are engaged in a lawsuit against the Department of the Interior for At its simplest, a tribe is a collective of American In- mismanaging funds held in trust for the tribes. A fed- dians (most historic U.S. documents refer to "Indi- eral court is deciding whether to hold current and