Driving Distance on the PGA and LPGA Tours, 1993-2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Golf Championships–Fedex St. Jude Invitational 2020

World Golf Championships–FedEx St. Jude Invitational 2020 VOLUNTEER APPLICATION TPC Southwind - Memphis, TN - July 27- August 2, 2020 One volunteer per application please. CONTACT INFORMATION: First Name M.I. Last Name Address City State Zip Code Home Phone Work Phone Cell Phone Email Address Secondary Mailing Address (optional) City State Zip Code Emergency Contact Phone Number Committee Preferences 1st) 2nd) 3rd) (See committee descriptions below. Some committees require additional services pre and post event.) Please circle desired A.M. and/or P.M. shifts below to indicate your availability. Some committees will not split shifts and will require a full day commitment. Note – This is a schedule guide to assist the coordinators and chairmen, it is NOT an actual schedule. 07/20 07/21 07/22 07/23 07/24 07/25 07/26 07/27 07/28 07/29 07/30 07/31 08/01 08/02 08/03 MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. A.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. P.M. Volunteer Package Men (Please circle size) Women (Please circle size) 1 Men’s Shirt S M L XL XXL XXXL 1 Women’s Shirt S M L XL XXL 1 Baseball Cap OR Visor one size fits all 1 Baseball Cap OR Visor one size fits all 1 Volunteer Badge -- Good Entire Tournament Week 1 Volunteer Badge -- Good Entire Tournament Week 1 Parking Pass -- Good Entire Tournament Week 1 Parking Pass -- Good Entire Tournament Week Optional Items Available Size Men/Women Quantity Price Total Additional Shirt (must be same size) $30.00 Additional Cap OR Visor $15.00 Bucket Hat S/M L/XL $25.00 Tickets Wednesday grounds tickets (limit 2 per day) $20.00 Thursday grounds tickets (limit 2 per day) $40.00 Friday grounds tickets (limit 2 per day) $50.00 Saturday grounds tickets (limit 2 per day) $50.00 Sunday grounds tickets (limit 2 per day) $50.00 Week-long grounds ticket (unlimited) $170.00 TOTAL Method of Payment Money Order Credit Card CC# Exp. -

Tournament Fact Sheet Golf Course Management Information Course

Acres of fairway: 39 Source of water: Well Acres of rough: 100 Drainage conditions: Fair 1421 Research Park Drive • Lawrence, KS 66049-3859 • 800- Sand bunkers: 85 472 -7878 • www.gcsaa.org Water hazards: 7 Tournament Fact Sheet Champions Tour Course characteristics Tucson Conquistadores Classic Primary Height of March 16 - 22, 2015 Grasses Cut Bermudagrass; Omni Tucson National Golf Resort & Spa Tees ryegrass; 0.375" Tucson, Ariz. overseeded Bermudagrass; Fairways ryegrass; 0.375" Golf Course Management overseeded Bermudagrass; Information Greens overseeded w/ Poa 0.105" trivialis GCSAA Class A Area Director of Agronomy: Bermudagrass Rough n/a Michael Petty (dormant) Availability to media: Contact Michael Petty by phone 520-2973161; email [email protected] Environmental Age: 53 management/features Native hometown: Bisbee, Ariz. Omni Tucson National Golf Resort & Spa does Years as a GCSAA member: 27 not overseed the rough on either course to help GCSAA affiliated chapter: reduce water demand. Omni Tucson National Cactus & Pine Golf Course also converted a nine hole, 67 acre course to Superintendents Association an 18 hole, 57 acre course. Years at this course: 28 Number of employees: 45 Previous tournament preparation: 1991-2006 Tucson Open, Omni Tucson National Golf Resort & Spa, Tucson, Unusual wildlife on the course Ariz. Previous tournaments hosted by facility: Ducks; Coots; Widgeons; Bobcats; Javelina 1991-2006 Tucson Open How Michael got involved in golf course Predominate species of trees on course: management: Michael started in the industry with a Allepo pines; Eucalyptus summer job. Course statistics Interesting notes about the course: Average tee size: 3,000 sq. ft. Nestled in the foothills of the Santa Catalina Tournament Stimpmeter: 11 ft. -

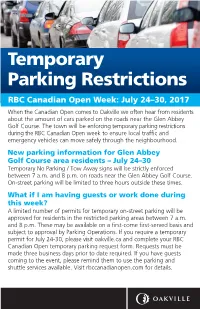

Temporary Parking Restrictions

Temporary Parking Restrictions RBC Canadian Open Week: July 24–30, 2017 When the Canadian Open comes to Oakville we often hear from residents about the amount of cars parked on the roads near the Glen Abbey Golf Course. The town will be enforcing temporary parking restrictions during the RBC Canadian Open week to ensure local traffic and emergency vehicles can move safely through the neighbourhood. New parking information for Glen Abbey Golf Course area residents – July 24–30 Temporary No Parking / Tow Away signs will be strictly enforced between 7 a.m. and 8 p.m. on roads near the Glen Abbey Golf Course. On-street parking will be limited to three hours outside these times. What if I am having guests or work done during this week? A limited number of permits for temporary on-street parking will be approved for residents in the restricted parking areas between 7 a.m. and 8 p.m. These may be available on a first-come first-served basis and subject to approval by Parking Operations. If you require a temporary permit for July 24-30, please visit oakville.ca and complete your RBC Canadian Open temporary parking request form. Requests must be made three business days prior to date required. If you have guests coming to the event, please remind them to use the parking and shuttle services available. Visit rbccanadianopen.com for details. Parking enforcement Emergency situations such as a blocked driveway or an obstructed fire route will be our priority. If you need parking enforcement, call 905-845-6601. -

Pgatourtpc.Com Course Statistics Twitter: @Nickbisanz Average Green Size: 4,300 Sq

Tournament Fact Sheet WGC-FedEx St. Jude Invitational TPC Southwind • Memphis, Tenn. • July 30-Aug. 2, 2020 Director of Golf Course Maintenance Tournament Set-up Nick Bisanz Par: 70 Phone: 901-748-4004 Yardage: 7,277 Cell: 480-773-9472 Email: [email protected] Course Statistics Twitter: @NickBisanz Average Green Size: 4,300 sq. ft. Average Tee Size: 2,500 sq. ft. Years as GCSAA Member: 17 Acres of Fairway: 22 Years at Course: 5 Acres of Rough: 115 Years as a Superintendent: 9 Number of Sand Bunkers: 75 Previous Courses: Heritage Golf Club (superintendent), Number of Water Hazards: 11 TPC Scottsdale (assistant), TPC Southwind (assistant), Number of Holes Water is in Play: 11 Atlanta Country Club (assistant) Soil Conditions: Clay Hometown: Marietta, Ga. Water Sources: Well Number of Employees: 28 Turfgrass Number of Tournament Volunteers: 30 Greens: Champion bermudagrass .090” Tees: Meyer zoysia .275” Other Key Golf Personnel Fairways: Meyer zoysia .425” Eddie Chittom, Assistant Superintendent Rough: 419 bermudagrass 2.5” Beau Farmer, Assistant Superintendent Weston Enos, Assistant Superintendent Additional Notes David Lopez, Equipment Manager • Changes to the course since last year’s PGA Professional: Larry Antinozzi tournament include a full bunker renovation, Club Manager: Burn Baine reshaping some bunkers, re-edging some bunkers, removal and addition of a few bunkers. Course Architect Architect (year): Ron Prichard (1988) with consultants • Other changes include shifting No. 3 Hubert Green and Fuzzy Zoeller fairway to the right 15 yards and Course Owner: PGA TOUR Golf Course Properties constructing a new tee that added 25 yards of length to the hole. • No. -

Lots of Changes for Tour Championship East Lake Renovated; New Date; No Woods

« GEORGIAPGA.COM GOLFFOREGEORGIA.COM « SEPTEMBER 2008 Lots of changes for Tour Championship East Lake renovated; new date; no Woods By Mike Blum G R record 23-under 257. Only three of 30 E B N I ust as in the Presidential race, the word D players were over par for the week, with E V E T 2-over 282 tying for last place. change will be closely associated with S the 2008 PGA Tour Championship “When you give these players soft presented by Coca-Cola. greens, they’re going to shoot lights out,” J Burton says. “It will be a lot different this Other than returning to East Lake for the fifth straight year – the eighth time year with greens that are firm and fast.” overall – with a field of 30 top PGA Tour East Lake closed for play March 1 and pros, there will be a lot of changes for this will not re-open until Tour Championship month’s event, with the tournament sched - week. Players and spectators will notice uled for Sept. 25-28. some changes to the course, which will still Since last year’s tournament, the course play to a par of 70 for the tournament has undergone renovations, stemming but has been lengthened to just over from the problems East Lake’s bent grass 7,300 yards. greens encountered from last summer’s Perhaps the most dramatic change is the hot, dry weather. addition of a new tee on the picturesque East Lake’s putting surfaces have been par-3 sixth hole, one of the first in golf to converted to mini-verde, an ultra-dwarf feature an island green. -

Discovery, GOLFTV Und Tiger Woods Präsentieren Die 2. Staffel Der Exklusiven Serie “MY GAME: TIGER WOODS”

Discovery, GOLFTV und Tiger Woods präsentieren die 2. Staffel der exklusiven Serie “MY GAME: TIGER WOODS” • Vom Tee zum Grün: "MY GAME: TIGER WOODS - SHOTMAKING SECRETS" bietet den Fans ein einzigartiges Tutorial zu jedem Schlag des Golf-Superstars • Gefilmt im Juni diesen Jahres im Dye Preserve in Jupiter, Fla. • Die Serie ist bei GOLFTV powered by PGA TOUR abrufbar; die erste Episode ist am 20. August frei verfügbar Die 2. Staffel “MY GAME: TIGER WOODS” mit Golfstar Tiger Woods (© Discovery Golf) London/München, 17. August 2020 – Golffans können sich auf neue Folgen der exklusiven Masterclass-Serie “MY GAME: TIGER WOODS” freuen: Discovery Golf und GOLFTV powered by PGA TOUR geben heute bekannt, dass die zweiten Staffel am 20. August weltweit Premiere feiert. In zehn Episoden zeigt Tiger Woods seinen Fans zum ersten Mal seine „Shotmaking Secrets“. Bereits in der ersten Staffel (2019), “MY GAME: TIGER WOODS – INSIDE THE MIND OF A CHAMPION”, gewährt Tiger Woods seinen Fans noch nie gezeigte Einblicke in seine Gedankenwelt und sein Spiel. Nun können sich Golf-Enthusiasten auf noch mehr Inhalte, Trainingsmethoden und Tipps von der Golf-Ikone freuen. In der zweiten Staffel thematisiert der 15-fache Major-Champion seine unvergleichbare Schwungtechnik und verrät die Geheimnisse, die ihn zu einem der besten Spieler aller Zeiten gemacht haben. Die Inhalte der Serie werden den Fans klar und einprägsam vermittelt, sodass sie wertvolle Golf-Lektionen und -tipps erhalten, welche sie auf ihr eigenes Spiel anwenden können. “MY GAME: TIGER WOODS - SHOTMAKING SECRETS" wurde im Juni 2020 auf dem Golfkurs des Dye Preserve in Jupiter, Fla., gefilmt, wobei strenge Covid-19- Sicherheitsvorkehrungen für die Produktion getroffen wurden. -

Better '09 for State's PGA Tour Pros?

GEORGIAPGA.COM GOLFFOREGEORGIA.COM «« FEBRUARY 2009 Better ’09 for state’s PGA Tour pros? Love, Howell off to quick early starts By Mike Blum nament in ’08, as did former Georgia sixth in regular season points for the ’09 opener, placing him within range of or most of Georgia’s contingent Bulldog Ryuji Imada . FedEdCup and ninth on the final money the top 50 in the World Rankings and a on the PGA Tour, the 2008 The rest of Georgia’s PGA Tour mem - list with almost $4 million. Masters berth. season was not a particularly bers had to wait another week or two to Cink’s ‘08 season was divided into two Imada scored his first PGA Tour win in F memorable one, although there start their ’09 campaigns, with a common disparate halves; before and after his win in four seasons in Atlanta, but will not get the were some exceptions. theme the hope that this year will be a Hartford. Other than his participation on opportunity to defend his title in the Duluth’s Stewart Cink more successful one than 2008. the Ryder Cup team, Cink’s post-victory defunct AT&T Classic. Imada had a pair and Sea Island’s Davis On the surface, Cink’s ‘08 season was an highlights were non-existent. And as well of runner-up finishes among three top- Love opened the extremely successful one. He scored his as he played the first six months of the fives early in ’08 and a near win in the Fall 2009 season in the first win in five years in Hartford, the site season, he let a win get away in Tampa and Series, ending the season 13th in earnings Mercedes-Benz of his first PGA Tour victory as a rookie in did not put up much of a fight in the with over $3 million. -

Championship Credentials and Information Enclosed

EAST LAKE GOLF CLUB ROUTES TO THE TOUR CHAMPIONSHIP HOME OF THE TOUR CHAMPIONSHIP The primary routes serving traffic: FROM THE NORTH: I-75 S and I-85 ¡¡ ¡ S to I-75/85 S or GA 400 to I-85 S ¡ to I-75/85 S. Exit I-75/85 S at ¡ ¡ Fulton Street and follow the ¡ signs to Turner Field Parking. East Lake Golf Club • Atlanta, Georgia FROM THE SOUTH: I-75/85 N. Exit ¡ After 33 weeks and 3 Playoff events, it all comes down to this -- THE TOUR Fulton Street and follow the signs September 24-28, 2008 Championship presented by Coca-Cola, the 2008 PGA TOUR Playoff Finale. to Turner Field Parking. FROM THE EAST: I-20 W to Capitol In 2007, Tiger Woods captured his second TOUR Championship presented Avenue or Hwy. 78 to I-285 S ¡ by Coca-Cola trophy and the inaugural FedExCup in stunning fashion. This to I-20 W to Capitol Avenue. year, the top 30 players on the PGA TOUR will compete head-to-head to On Capitol Avenue go south and ¡ claim victory at THE TOUR Championship and determine the 2008 winner of follow signs to Turner Field Parking. the FedExCup. FROM THE WEST: I-20 E. Exit at Windsor Street and go south to Fulton Street following signs to Turner Field Parking. Peak traffic hours are expected to be Mark your calendars for Atlanta’s premier annual sporting event in 2009. from 10:00 AM until 1:00 PM. SEPTEMBER 14 – 20, 2009 GENERAL PUBLIC PARKING AND SHUTTLE INSTRUCTIONS THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS All Championship public parking is located at Turner Field off I-75/85 just south of downtown Atlanta. -

Rocco Mediate

Rocco Mediate Representerar United States (USA) Född Status Proffs Huvudtour SGT-spelare Nej Aktuellt Ranking 2021 Rocco Mediate har inte startat säsongen. Karriären Totala prispengar 1997-2021 Rocco Mediate har följande facit så här långt i karriären: (officiella prispengar på SGT och världstourerna) Summa Största Snitt per 4 segrar på 370 tävlingar. För att vinna dessa 4 tävlingar har det krävts en snittscore om 67,63 kronor prischeck tävling slag, eller totalt -66 mot par. I snitt per vunnen tävling gick Rocco Mediate -16,50 i förhållande År Tävl mot par. Segrarna har varit värda 21 560 400 kr. 1997 24 1 857 252 377 910 77 385 Härutöver har det också blivit: 1998 24 3 076 185 648 000 128 174 - 7 andraplatser. - 2 tredjeplatser. 1999 25 7 641 074 4 158 000 305 643 - 19 övriga topp-10-placeringar 2000 24 11 790 112 4 471 200 491 255 - 38 placeringar inom 11-20 2001 21 14 760 213 4 168 800 702 867 - 157 övriga placeringar på rätt sida kvalgränsen - 12 missade kval 2002 22 19 985 162 7 045 200 908 416 Med 227 klarade kval på 239 starter är kvalprocenten sålunda 95. 2003 24 15 469 628 4 590 000 644 568 Sammantaget har Rocco Mediate en snittscore om 71,10 slag, eller totalt -280 mot par. 2004 19 1 908 627 627 000 100 454 2005 24 5 307 457 1 440 526 221 144 2006 18 1 093 579 287 620 60 754 2007 21 7 955 098 4 128 300 378 814 2008 26 8 571 858 4 924 800 329 687 2009 22 3 711 710 537 328 168 714 2010 25 7 343 908 5 886 000 293 756 2011 23 901 097 380 800 39 178 2012 22 1 633 895 323 914 74 268 2013 1 0 0 0 2014 2 0 0 0 2015 1 0 0 0 2016 2 271 -

Player Game Guide

Navy Gold Coast 2018 and NDIA San Diego Patriot Golf Day Welcome to the Navy Gold Coast 2018 and NDIA San Diego Patriot Golf Day Benefiting the FOR EVERY WAVING FLAG, THERE ARE Folds of Honor Foundation THOUSANDS FOLDED. This year, for the third time in event history, the greatest golfer of all time, Jack Nicklaus, has joined PLAYER Folds of Honor as Honorary Chairman of Patriot Golf Day®. Since 2007, Patriot Golf Day® has GAME GUIDE helped raise money for educational scholarships Courtesy of INDUS Technology, Inc. for deserving military families. Join Jack, and help us continue to change lives through the game of golf at your local course. Honor, with respect to golf, is more than “the privilege of playing first from the tee.” • A qualified player is one who has purchased the On-Course Contest Package, either as a single or as a foursome. • Max Score on any hole: Bogey. Pick up and move to the next hole. • Pace of Play. Please endeavor to complete each hole in 15 minutes or less. Hole 1: Win a Game, Play Up. Each qualified player of the foursome participates in the pre-tee off contest. If any qualified player of the foursome wins the pre-tee off contest, the foursome’s first strokes MAY be taken from the designated area about 110 yards below the hole in the center of the fairway. If no player wins the game, each player of the foursome takes their tee shot from his or her designated teeing ground and plays in accordance with the Patriot Golf Day scramble rules. -

The Tournament Catalog

Tournament & Event Catalog Tournament & Event Catalog Table of Contents EXPERIENCE THE Welcome . .1 PLACE ON TURF About the Walt Disney World® Golf Courses . .2 Catering and Culinary Opportunities . .3 Breakfast Selections . .4 Boxed Lunches . .5 L o e r Refreshment Carts . .6 m Rental Equipment at Walt Disney World® Golf . .7 Event Merchandise . .8 Event Merchandise Packages . .9 Host of the PGA Tour’s Walt Disney World® Instruction Clinics . .10 Walt Disney World® Golf Classic from Transportation Options . .11 1971 to 2012 Other Optional Experiences . .12 Three championship Character Appearances, Night Golf Skills, Long Drive Demo courses rated to “Places to Play” by Golf Digest Walt Disney World® Map . .13 Located in Walt Disney World® – the #1 travel destination in the US 407-WDW-GOLF I www. golfwdw.com A TRADITIONAL G OLF EXPERIENCE Welcome to the “Happiest Place on Turf!” We offer facilities and services to players of all ages and skill levels! Tournaments From beautiful scenery to challenging twists and turns, the magic of Walt Disney World® Golf serves as the perfect backdrop for your next group outing. We provide a wide range of tournament services, and our dedicated professional staff will help guide you from pre-event planning through the course of your event, ensuring a magical experience for all who participate. Special Events Our Walt Disney World® Golf professional staff can craft and conduct exciting Team Building programs for any group. Some of our popular events include the Putting Relay, Putting Archery, Long Drive, Hole-in-One Contest, or Night Skills Contests. These options can be coordinated during a group’s arrival, opening reception, or whenever your schedule allows, and can be incorporated with food and drinks from our talented culinary staff for a truly unique event. -

Drive Shack Into New Markets • Hana Khouri Became President After Q2 Miss Amd Was Also Part of Topgolf Team • Currently, CEO on Leave of Absence Recent Developments

Pitch: Long DriveShack 11/8/2019 Larry Wang, Srikar Alluri, Simran Korpal, Tony Wang, Catie Wang 0 Agenda 1 Team Introductions 2 Company Overview 3 Industry Overview 4 Thesis Points 5 Risks and Catalysts 6 Valuation 1 The Pitch Team Larry Wang Simran Korpal Srikar Alluri Senior Analyst Junior Analyst Junior Analyst Class of 2021 Class of 2022 Class of 2022 Catie Wang Tony Wang Junior Analyst Junior Analyst Class of 2023 Class of 2023 2 Company Overview 3 Company Overview Introduction Video Company Industry Investment Catalysts and Valuation Appendix Overview Overview Thesis Risks 4 Company Overview Entertainment Driving Ranges Business Segments Demographic Shift • Entertainment Golf – combination of golfing, dining and a fun experience. Three opening in Not the Typical Golf 2019, 3-5 in 2020, and 30 more in the pipeline. Player Currently have 4 open venues. Entertainment Golf • Traditional Golf – Owns and operates 66 attracts a younger crowd properties through American Golf. Operates in and more families three categories 68% of males who go are • Public Properties – revenue comes from 34 years or younger daily operation fees 23% of women golf • Private Properties – revenue comes from versus 35% go to membership Entertainment Golf • Managed Properties – management fees venues with high margin More than Just Golf • 60 dollar cost per person despite the actual cost of the game being ~ $40 per person – 38% of revenue • Upselling with food and drinks • Food and Entertainment provides more of a family orientated entertainment business (unlike