Implied…Or Implode? the Simpsons' Carnivalesque Treehouse of Horror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Postmodernism: the American T.V. Show, 'Family Guy, As a Politically Incorrect Document

Postmodernism: The American T.V. Show, 'Family Guy, As a Politically Incorrect Document Tyron Tyson Smith1; Ajit Duara2* 1Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India. 2*Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India. 2*[email protected] Abstract Postmodernism is a movement that grew out of modernism. Movements in art, literature, and cinema focused on a particular stance. The visual artists who created entertainment focused on expressing the creator herself/himself beginning from German expressionism to modernism, surrealism, cubism, etc. These art movements played an important part in what an artist (literature, art, and visual) portrayed to his or her audience. As perspectives played an important part, an understanding of what the artist needed to portray was critical. Modernism dealt with this portrayal, which came about due to the changes taking place in society. In terms of the industry, where the overall product dealt with features like individualism, experimentation and absurdity, modernism dealt with a need to overthrow past notions of what painting, literature, and the visual arts needed to be. "After World War II, the focus moved from Europe to the United States, and abstract expressionism (led by Jackson Pollock) continued the movement's momentum, followed by movements such as geometric abstractions, minimalism, process art, pop art, and pop music." Postmodernism helped do away with these shortcomings. An understanding of postmodernism is explored in this paper. The main point which sets it apart is concepts like pastiche, intersexuality, and spectacle. Concerning pop culture, an understanding of referencing is a constant trait used by postmodern art. -

Mediasprawl: Springfield U.S.A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Iowa Research Online Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies Volume 3, Issue 1 2003 Article 10 SUBURBIA Mediasprawl: Springfield U.S.A Douglas Rushkoff∗ ∗ Copyright c 2003 by the authors. Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://ir.uiowa.edu/ijcs Mediasprawl: Springfield U.S.A. Douglas Rushkoff The Simpsons are the closest thing in America to a national media literacy program. By pretending to be a kids’ cartoon, the show gets away with murder: that is, the virtual murder of our most coercive media iconography and techniques. For what began as entertaining interstitial material for an alternative network variety show has revealed itself, in the twenty-first century, as nothing short of a media revolu tion. Maybe that’s the very reason The Simpsons works so well. The Simpsons were bom to provide The Tracey Ullman Show with a way of cutting to commercial breaks. Their very function as a form of media was to bridge the discontinuity inherent to broadcast television. They existed to pave over the breaks. But rather than dampening the effects of these gaps in the broadcast stream, they heightened them. They acknowledged the jagged edges and recombinant forms behind the glossy patina of American television and, by doing so, initiated its deconstruction. They exist in the outlying suburbs of the American media landscape: the hinter lands of the Fox network. And living as they do—simultaneously a part of yet separate from the mainstream, primetime fare—they are able to bear witness to our cultural formulations and then comment upon them. -

ICE - Volumes of Revolution

A ICE - Volumes of Revolution In an episode1 of the popular television program, “The Simpsons,” Homer Simpson (see Figure 12) became the conductor of Springfield’s monorail. The episode began with Homer leaving his job at the nuclear power plant singing: Homer, Homer Simpson, He’s the greatest guy in history. From the town of Springfield, He’s about to hit a chestnut tree. After Homer’s car crash, Mr. Burns and Smithers were caught dumping toxic waste from the nuclear power plant. Mr. Burns was fined three million dollars. The Figure 1: Homer J. Simpson. people of Spingfield met to discuss how to spend this windfall, when fast-talking music man Lyle Lanley persuaded them to spend it all on a monorail. Lyle Lanley: Well, sir, there’s nothing on Earth like a genuine, bona fide, electrified, six- car monorail! What’d I say? Ned Flanders: Monorail! Lyle Lanley: What’s it called? Patty and Selma: Monorail! Lyle Lanley: That’s right – Monorail! (Crowd softly chants “Monorail” in rhythm.) Miss Hoover: I hear those things are awfully loud. Lyle Lanley: It glides as softly as a cloud. Apu: Is there a chance the track could bend? Lyle Lanley: Not on your life, my Hindu friend. Barney: What about us brain-dead slobs? Lyle Lanley: You’ll all be given cushy jobs. Abraham Simpson (Grandpa): Were you sent here by the devil? Lyle Lanley: No, good sir, I’m on the level. Chief Wiggum: The ring came off my pudding can. Lyle Lanley: Use my pen knife, my good man. -

Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in the Simpsons

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Craptacular Science and the Worst Audience Ever: Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in The Simpsons being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD Film Studies in the University of Hull by Jemma Diane Gilboy, BFA, BA (Hons) (University of Regina), MScRes (University of Edinburgh) April 2016 Craptacular Science and the Worst Audience Ever: Memetic Proliferation and Fan Participation in The Simpsons by Jemma D. Gilboy University of Hull 201108684 Abstract (Thesis Summary) The objective of this thesis is to establish meme theory as an analytical paradigm within the fields of screen and fan studies. Meme theory is an emerging framework founded upon the broad concept of a “meme”, a unit of culture that, if successful, proliferates among a given group of people. Created as a cultural analogue to genetics, memetics has developed into a cultural theory and, as the concept of memes is increasingly applied to online behaviours and activities, its relevance to the area of media studies materialises. The landscapes of media production and spectatorship are in constant fluctuation in response to rapid technological progress. The internet provides global citizens with unprecedented access to media texts (and their producers), information, and other individuals and collectives who share similar knowledge and interests. The unprecedented speed with (and extent to) which information and media content spread among individuals and communities warrants the consideration of a modern analytical paradigm that can accommodate and keep up with developments. Meme theory fills this gap as it is compatible with existing frameworks and offers researchers a new perspective on the factors driving the popularity and spread (or lack of popular engagement with) a given media text and its audience. -

Press Contacts for the Television Academy: 818-264

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Post-awards presentation (approximately 7:00PM, PDT) September 11, 2016 WINNERS OF THE 68th CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. - September 11, 2016) The Television Academy tonight presented the second of 2016 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards ceremonies for programs and individual achievements at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles and honored variety, reality and documentary programs, as well as the many talented artists and craftspeople behind the scenes who create television excellence. Executive produced by Bob Bain, this year’s Creative Arts Awards featured an array of notable presenters, among them Derek and Julianne Hough, Heidi Klum, Jane Lynch, Ryan Seacrest, Gloria Steinem and Neil deGrasse Tyson. In recognition of its game-changing impact on the medium, American Idol received the prestigious 2016 Governors Award. The award was accepted by Idol creator Simon Fuller, FOX and FremantleMedia North America. The Governors Award recipient is chosen by the Television Academy’s board of governors and is bestowed upon an individual, organization or project for outstanding cumulative or singular achievement in the television industry. For more information, visit Emmys.com PRESS CONTACTS FOR THE TELEVISION ACADEMY: Jim Yeager breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-264-6812 Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-462-1150 TELEVISION ACADEMY 2016 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SUNDAY The awards for both ceremonies, as tabulated by the independent -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

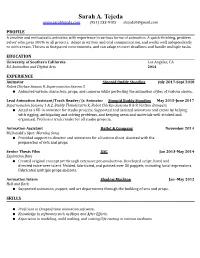

Sarah A. Tejeda (951) 233-9185 [email protected]

Sarah A. Tejeda www.sarahtejeda.com (951) 233-9185 [email protected] PROFILE A creative and enthusiastic animator, with experience in various forms of animation. A quick-thinking, problem solver who gives 100% to all projects. Adept in written and oral communication, and works well independently or with a team. Thrives in fast-paced environments, and can adapt to meet deadlines and handle multiple tasks. EDUCATION University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA BA Animation and Digital Arts 2014 EXPERIENCE Animator Stoopid Buddy Stoodios July 2017-Sept 2018 Robot Chicken Season 9, Supermansion Season 3 ● Animated various characters, props, and cameras while perfecting the animation styles of various shows. Lead Animation Assistant/Track Reader/ Jr. Animator Stoopid Buddy Stoodios May 2015-June 2017 Supermansion Seasons 1 & 2, Buddy Thunderstruck, Robot Chicken Seasons 8 & 9, Verizon Bumpers ● Acted as a fill-in animator for studio projects. Supported and assisted animators and crews by helping with rigging, anticipating and solving problems, and keeping areas and materials well-stocked and organized. Proficient track reader for all studio projects. Animation Assistant Hello! & Company November 2014 McDonald’s Spot: Morning Song ● Provided support to director and animators for a location shoot. Assisted with the preparation of sets and props. Senior Thesis Film USC Jan 2013-May 2014 Expiration Date ● Created original concept art through extensive pre-production. Developed script, hired and directed voice-over talent. Molded, fabricated, and painted over 30 puppets, including facial expressions. Fabricated multiple props and sets. Animation Intern Shadow Machine Jan -May 2012 Hell and Back ● Supported animation, puppet, and art departments through the building of sets and props. -

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

TV Listings Aug21-28

SATURDAY EVENING AUGUST 21, 2021 B’CAST SPECTRUM 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 2 2Stand Up to Cancer (N) NCIS: New Orleans ’ 48 Hours ’ CBS 2 News at 10PM Retire NCIS ’ NCIS: New Orleans ’ 4 83 Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ Grace Paid Prog. ThisMinute 5 5Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ 1st Look In Touch Hollywood 6 6Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ FOX 6 News at 9 (N) News (:35) Game of Talents (:35) TMZ ’ (:35) Extra (N) ’ 7 7Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News at 10pm Castle ’ Castle ’ Paid Prog. 9 9MLS Soccer Chicago Fire FC at Orlando City SC. Weekend News WGN News GN Sports Two Men Two Men Mom ’ Mom ’ Mom ’ 9.2 986 Hazel Hazel Jeannie Jeannie Bewitched Bewitched That Girl That Girl McHale McHale Burns Burns Benny 10 10 Lawrence Welk’s TV Great Performances ’ This Land Is Your Land (My Music) Bee Gees: One Night Only ’ Agatha and Murders 11 Father Brown ’ Shakespeare Death in Paradise ’ Professor T Unforgotten Rick Steves: The Alps ’ 12 12 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News Big 12 Sp Entertainment Tonight (12:05) Nightwatch ’ Forensic 18 18 FamFeud FamFeud Goldbergs Goldbergs Polka! Polka! Polka! Last Man Last Man King King Funny You Funny You Skin Care 24 24 High School Football Ring of Honor Wrestling World Poker Tour Game Time World 414 Video Spotlight Music 26 WNBA Basketball: Lynx at Sky Family Guy Burgers Burgers Burgers Family Guy Family Guy Jokers Jokers ThisMinute 32 13 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ News Flannery Game of Talents ’ Bensinger TMZ (N) ’ PiYo Wor. -

Spring 2003 Vancouver Prime Time TV Schedules 7 P.M

Spring 2003 Vancouver Prime Time TV Schedules 7 p.m. - 11 p.m. February 22 - March 15, 2003 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 7 Air Farce On the Road Again Mr. Bean Life & Times Movie It’s a Living 22 Minutes Mr. Bean Opening Night 8 22 Minutes Air Farce NHL Hockey Last Chapter Wind at My Back Marketplace Red Green Anne Murray 9 American in Canada Disclosure Fifth Estate Witness Nature of Things Made in Canada After Hours 10 Sunday Report The National At the End CBUT Venture 7 Entertainment Tonight Body & Health The Simpsons Bob & Margaret Reba Bob & Margaret Friends Blackfly State of the Heart King of the Hill 8 70s Show The Simpsons Boston Public Let's Make a Deal Survivor Dawson's Creek PSI Factor Popstars Greek Life 9 Frasier Will & Grace Malcolm Married by America Married by America Hack Mutant X A.U.S.A Popstars Raymond 10 Crossing Jordan Judging Amy Gilmore Girls Without a Trace Blue Murder Andromeda Dragnet CHAN 7 Blind Date Fashion TV Speakers Corner Fifth Wheel StarTV DiverseCITY 8 CHUM The Immortal Smallville Enterprise Joe Millionare Lexx First Wave Dead Man's Gun 9 Joe Millionaire Movie I'm A Celebrity Are You Hot? Movie Movie Movie 10 Blind Date Movie Movie All American Girl Lexx CKVU Fifth Wheel 7 Friends Oliver Beene Mysterious Ways Access Hollywood Degrassi 8 8 Simple Rules My Wife & Kids Just for Laughs American Idol Fastlane Law & Order Alias According to Jim American Idol Scrubs 9 Third Watch CSIWest Wing CSI W-Five Figure Skating Law & Order 10 CSI Miami The SopranosLaw & Order ER Law & Order -

Superperforming Ceo

THE SUPERPERFORMING CEO THE SUPERPERFORMING Management/Leadership U.S. $14.95 Canada $18.20 U.K £ 8.50 The Superperforming CEO Uncommon Sense for Uncommon Results In his latest book, Dave Guerra introduces 15 unconventional strategies for executives who seek to achieve Superperforming levels of organizational performance, stakeholder engagement, and shareholder return on investment. Through a multi-year conversation with Superperforming CEO George Martinez, CEO of Allegiance Bank Texas and former Chairman and CEO of Sterling Bancshares, Guerra elucidates 15 Distinctions for today’s executives that any leader can use to turn organizations into places where systems sing and spirits soar. Liberating the Promise Within Liberating the Promise Replete with both hard-hitting statistics and illustrative anecdotes, Guerra explores the uncommon people, uncommon practices and uncommon paradigms that reveal the fully expressed right brain of a Superperforming CEO. Drawing on new science principles including complementarity, emergence, and increasing returns, Guerra demonstrates why dramatic change is possible and how it can occur. The real-life experiences and the penetrating insight that Martinez offers clearly provide credence, and his enthusiasm for people, processes and performance is contagious. To learn more about Superperformance and The Superperforming CEO visit www.corpusoptima.com or call 832-497-1283. LIBERATING the PROMISE WITHIN Cover Design by Axiom, Houston SuperperformingThe CEO LIBERATING the PROMISE WITHIN Uncommon Sense for Uncommon Results DAVE Guerra Copyright © 2009 Dave Guerra All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America This book may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Dave Guerra. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively.