New Media and the White Cube

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preserving New Media Art: Re-Presenting Experience

Preserving New Media Art: Re-presenting Experience Jean Bridge Sarah Pruyn Visual Arts & Interactive Arts and Science, Theatre Studies, University of Guelph, Brock University Guelph, Canada St. Catharines, Canada [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Keywords There has been considerable effort over the past 10 years to define methods for preservation, documentation and archive of new Art, performance art, relational art, interactive art, new media, art media artworks that are characterized variously as ephemeral, preservation, archive, art documentation, videogame, simulation, performative, immersive, participatory, relational, unstable or representation, experience, interaction, aliveness, virtual, technically obsolete. Much new media cultural heritage, authorship, instrumentality consisting of diverse and hybrid art forms such as installation, performance, intervention, activities and events, are accessible to 1. INTRODUCTION us as information, visual records and other relatively static This investigation has evolved from our interest in finding documents designed to meet the needs of collecting institutions documentation of artwork by artists who produce technologically and archives rather than those of artists, students and researchers mediated installations, performances, interventions, activities and who want a more affectively vital way of experiencing the artist’s events - the nature of which may be variously limited in time or creative intentions. It is therefore imperative to evolve existing duration, performance based, -

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020 James MacDevitt, M.A. Associate Professor of Art History and Visual & Cultural Studies Director, Cerritos College Art Gallery Department of Art and Design Fine Arts and Communications Division Cerritos College January 2021 Table of Contents Title Page i Table of Contents ii Sabbatical Leave Application iii Statement of Purpose 35 Objectives and Outcomes 36 OER Textbook: Disciplinary Entanglements 36 Getty PST Art x Science x LA Research Grant Application 37 Conference Presentation: Just Futures 38 Academic Publication: Algorithmic Culture 38 Service and Practical Application 39 Concluding Statement 40 Appendix List (A-E) 41 A. Disciplinary Entanglements | Table of Contents 42 B. Disciplinary Entanglements | Screenshots 70 C. Getty PST Art x Science x LA | Research Grant Application 78 D. Algorithmic Culture | Book and Chapter Details 101 E. Just Futures | Conference and Presentation Details 103 2 SABBATICAL LEAVE APPLICATION TO: Dr. Rick Miranda, Jr., Vice President of Academic Affairs FROM: James MacDevitt, Associate Professor of Visual & Cultural Studies DATE: October 30, 2018 SUBJECT: Request for Sabbatical Leave for the 2019-20 School Year I. REQUEST FOR SABBATICAL LEAVE. I am requesting a 100% sabbatical leave for the 2019-2020 academic year. Employed as a fulltime faculty member at Cerritos College since August 2005, I have never requested sabbatical leave during the past thirteen years of service. II. PURPOSE OF LEAVE Scientific advancements and technological capabilities, most notably within the last few decades, have evolved at ever-accelerating rates. Artists, like everyone else, now live in a contemporary world completely restructured by recent phenomena such as satellite imagery, augmented reality, digital surveillance, mass extinctions, artificial intelligence, prosthetic limbs, climate change, big data, genetic modification, drone warfare, biometrics, computer viruses, and social media (and that’s by no means meant to be an all-inclusive list). -

View and Download the File

THROUGH THE BARRICADES DECEMBER 3RD 20I5 > JANUARY I0TH 20I6 FABBRICA DEL VAPORE, MILAN Promoted by BJCEM, Biennale des jeunes créateurs 2 de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée Municipality of Milan Board of Directors Helen Andreou, Selim Birsel, Keith Borg, Isabelle Bourgeois, Rita Canarezza, Miguel Cascales Tarazona, Petros Dymiotis, Claudio Grillone, Paulo Gouveia, France Irrmann, BJCEM - BIENNALE DES JEUNES CRÉATEURS Maria del Gozo Merino Sanchez, Nina Mudrinic Milovanovic, Said Murad, Abdo Nawar, Ksenija Orelj, Leonardo Punginelli, DE L’EUROPE ET DE LA MÉDITERRANÉE Mohamed Rafik Khalil, Raphael Sage, Ana Savjak, Jernej Skof, Ibrahim Spahić, Carlo Testini, Eleni Tsevekidou, Luis Verde Godoy BJCEM Members Arci Bari (Italy), Arci Emilia Romagna (Italy), Arci Lazio (Italy), Arci President Milano (Italy), Arci Nazionale (Italy), Arci Pescara (Italy), Arci Regionale Emilia Romagna (Italy), Arci Regionale Liguria (Italy), Arci Regionale Dora Bei Puglia (Italy), Arci Regionale Sardegna (Italy), Arci Regionale Sicilia (Italy), Arci Torino (Italy), Atelier d’Alexandrie (Egypt), Ayuntamiento de General Secretary Madrid (Spain), Ayuntamiento de Malaga (Spain), Ayuntamiento de Murcia (Spain), Ayuntamiento de Salamanca (Spain), Ayuntamiento de Sevilla Federica Candelaresi (Spain), Ayuntamiento de Valencia (Spain), Centar za Savremenu Umetnost Strategie Art (Serbia), Città di Torino (Italy), Città di Venezia (Italy), City Treasurer of Thessaloniki (Greece), Clube Português de Artes e Ideias (Portugal), Helen Andreou Comune di Ancona (Italy), Comune -

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

Nicolas Bourriaud Postproduction Culture As Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World 11 Has & Sternberg, New York

NICOLAS BOURRIAUD POSTPRODUCTION CULTURE AS SCREENPLAY: HOW ART REPROGRAMS THE WORLD 11 HAS & STERNBERG, NEW YORK CONTENTS Nicolas Bourriaud PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION Postproduction Publisher: Lukas & Sternberg, New York INTRODUCTION © 2002 Nicolas Bourriaud, Lukas & Sternberg All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. THE USE OF OBJECTS THE USE OF THE PRODUCT FROM MARCEL DUCHAMP First published 2002 (0-9711193-0-9) TO JEFF KOONS Reprinted with new preface 2005 THE FLEA MARKET: THE DOMINANT ART FORM OF THE NINETIES - -,.- •-••.• Editor: Caroline Schneider Translation: Jeanine Herman THE USE OF FORMS Copy Editors: Tatjana Giinthner, Radhika Jones, John Kelsey DEEJAYING AND CONTEMPORARY ART: SIMILAR Design: Sandra Kastl, Markus Weisbeck, surface, Berlin /Frankfurt CONFIGURATIONS Printing and binding: Medialis, Berlin WHEN SCREENPLAYS BECOME FORM: A USER'S GUIDE ISBN 0-9745688-9-9 TO THE WORLD . THE USE OF THE WORLD 69 Lukas & Sternberg PLAYING THE WORLD: REPROGRAMMING SOCIAL FORMS 69 Caroline Schneider HACKING, WORK, AND FREE TIME 1182 Broadway #1602, New York NY 10001 LinienstraBe 159, D-10115 Berlin HOW TO INHABIT GLOBAL CULTURE [email protected], www.lukas-sternberg.com (AESTHETICS AFTER MP3) I PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION Since its initial publication in 2001, Postproduction has been trans- lated into five languages; depending on the translation schedules in various countries, publication either overlapped with or preceded that of another of my books, Esthetique relationnelle (Relational Aesthetics), written five years earlier. The relationship between these two theoret- ical essays has often been the source of a certain misunderstanding, if not malevolence, on the part of a critical generation that knows itself to be slowing down and counters my theories with recitations from "The Perfect American Soft Marxist Handbook" and a few vestiges of Greenbergian catechism. -

Read a Free Sample

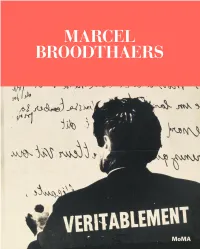

MARCEL BROODTHAERS A RETROSPECTIVE Manuel J. Borja-Villel Christophe Cherix With contributions by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh Cathleen Chaffee Jean-François Chevrier Kim Conaty Thierry de Duve Rafael García Doris Krystof Christian Rattemeyer Sam Sackeroff Teresa Velázquez Francesca Wilmott The Museum of Modern Art, New York Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid CONTENTS Directors’ Foreword / 7 Glenn D. Lowry, Manuel J. Borja-Villel, and Marion Ackermann Acknowledgments Maria Gilissen Broodthaers, followed by a conversation with Yola Minatchy / 9 Manuel J. Borja-Villel and Christophe Cherix / 12 I Am Not a Filmmaker: Notes on a Retrospective / 16 Manuel J. Borja-Villel and Christophe Cherix Rhetoric, System D; or Poetry in Bad Weather / 22 Jean-François Chevrier Figure Zero / 30 Thierry de Duve First and Last: Two Books by Marcel Broodthaers / 40 Benjamin H. D. Buchloh Poetry, Photographs, and Films Sam Sackeroff and Teresa Velázquez 52 Objects Rafael García and Francesca Wilmott 76 The Object and Its Reproduction Francesca Wilmott 116 Literary Exhibitions Sam Sackeroff 136 Le Corbeau et le Renard 140 Exposition littéraire autour de Mallarmé 156 Musée–Museum Christian Rattemeyer 166 Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles 172 The Düsseldorf Years Doris Krystof 216 Related Works 224 Emblems of Authority Cathleen Chaffee 248 Paintings Kim Conaty 270 Décors Cathleen Chaffee 290 Exhibition History / 330 Selected Bibliography / 336 Catalogue of the Exhibition and Illustrated Works / 340 Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art / 350 6 7 DIRECTORS’ FOREWORD Marcel Broodthaers is an artist’s artist. Although he is not generally widely known, he has had a profound influence on the generations of artists that have followed, and any museum committed to contemporary art crosses path with his legacy at some point. -

Chapter 12. the Avant-Garde in the Late 20Th Century 1

Chapter 12. The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century 1 The Avant-Garde in the Late 20th Century: Modernism becomes Postmodernism A college student walks across campus in 1960. She has just left her room in the sorority house and is on her way to the art building. She is dressed for class, in carefully coordinated clothes that were all purchased from the same company: a crisp white shirt embroidered with her initials, a cardigan sweater in Kelly green wool, and a pleated skirt, also Kelly green, that reaches right to her knees. On her feet, she wears brown loafers and white socks. She carries a neatly packed bag, filled with freshly washed clothes: pants and a big work shirt for her painting class this morning; and shorts, a T-shirt and tennis shoes for her gym class later in the day. She’s walking rather rapidly, because she’s dying for a cigarette and knows that proper sorority girls don’t ever smoke unless they have a roof over their heads. She can’t wait to get into her painting class and light up. Following all the rules of the sorority is sometimes a drag, but it’s a lot better than living in the dormitory, where girls have ten o’clock curfews on weekdays and have to be in by midnight on weekends. (Of course, the guys don’t have curfews, but that’s just the way it is.) Anyway, it’s well known that most of the girls in her sorority marry well, and she can’t imagine anything she’d rather do after college. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Towards a Politics of (Relational) Aesthetics by Anthony Downey

This article was downloaded by: [Swets Content Distribution] On: 8 February 2009 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 902276281] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Third Text Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713448411 Towards a Politics of (Relational) Aesthetics Anthony Downey Online Publication Date: 01 May 2007 To cite this Article Downey, Anthony(2007)'Towards a Politics of (Relational) Aesthetics',Third Text,21:3,267 — 275 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/09528820701360534 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09528820701360534 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Third Text, Vol. 21, Issue 3, May, 2007, 267–275 Towards a Politics of (Relational) Aesthetics Anthony Downey 1 The subject of aesthetics The aesthetic criteria used to interpret art as a practice have changed and art criticism has been radically since the 1960s. -

N. 17 Dicembre 2017/Marzo 2018 a Painting by Hans Haacke

n. 17 dicembre 2017/marzo 2018 A Painting by Hans Haacke : Dematerializing Labor di Andreas Petrossiants Artistic activity is a mode – a singular form – of labor power . Antonio Negri, 2008 1 To center an essay concerning the more - than - expansive discursive field denoted by «painting», on just one work by Hans Haacke, might at first glance seem misplaced. However, while Haacke’s work was surely instrumental for the shifts in Western artistic pra ctice comprising the «conceptual turn» of the 1960s and the parallel «dematerialization» of the art object, his painting Taking Stock (unfinished) (1983 - 1984 ) not only brings such broad period generalizations into question, but also examines the labor invo lved in producing (the value of) a painting [fig. 1]. Taking Stock (unfinished) , first exhibited at the Tate Gallery in 1984, depicts Margaret Thatcher in the style of Victorian portraiture, encoded with information concerning the careers and art collectio ns of Charles and Doris Saatchi, as well as their ties to Thatcher and her reactionary government. Referring specifically to the medium and style of the work, Haacke remarks that it was produced to cite and critique how Thatcher «expressly promotes Victori an values, nineteenth century conservative policies at the end of the twentieth century». He continues: « Thatcher would like to rule an imperial Britain. The Falklands War was typical of this mentality». 2 This essay proposes to displace and problematize the traditional discourses applied to historicizing conceptual art, and to describe how Haacke employs both physical «painterly» and immaterial conceptual labor to produce a material object. He fosters a str ategy mirroring the changes in the structure and critical position of the (art) worker 1 during the late 1960s. -

Postinternet, Its Art and (The) New Aesthetic

POSTINTERNET, ITS ART AND (THE) NEW AESTHETIC — A Conceptual Framework for Art Education POSTINTERNET, ITS ART AND (THE) NEW AESTHETIC — A Conceptual Framework for Art Education Elina Nissinen Master of Arts thesis, 30 ECTS Supervisor Kevin Tavin Master’s Program in Art Education Department of Art Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture 2018 Author Elina Nissinen Työn nimi Postinternet, Its Art and (The) New Aesthetic – A Conceptual Framework for Art Education Department Department of Art Degree programme Master’s program in Art Education Year 2018 Number of pages 83 Language English Abstract As one might expect from terms employing the prefixes ‘post’ or ‘new,’ combined with the words ‘internet,’ ‘art,’ and ‘aesthetic,’ postinternet, postinternet art (PIA), and New Aesthetic ((the) NA) are broad and disputable concepts. I started this study because I noticed that these ambiguous, yet widely- discussed terms were hardly acknowledged in art education. This thesis provides a conceptual framework for postinternet, PIA, and (the) (the) NA through a critical review of the literature. Postinternet and (the) NA are notions and phenomena that signpost an era and a condition of unprecedented pace of computation-driven transformations in the human culture. They continue the list of theoretical neologisms indicating the changes brought about by the post-conditions. This thesis establishes that postinternet, PIA, and (the) NA are characterized through their paradoxical relation to time and temporality at conceptual and thematical levels. Obsessed with novelty, these terms attempt to break off from their “previous,” while, starting from their titles, simultaneously anchoring themselves to the past. Postinternet is a notion that describes the inescapable consequences of the intermixing of the online and offline, the omnipresence of the internet. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R.