The Soviet Union, Lithuania and the Establishment of the Baltic Entente *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Akasvayu Girona

AKASVAYU GIRONA OFFICIAL CLUB NAME: CVETKOVIC BRANKO 1.98 GUARD C.B. Girona SAD Born: March 5, 1984, in Gracanica, Bosnia-Herzegovina FOUNDATION YEAR: 1962 Career Notes: grew up with Spartak Subotica (Serbia) juniors…made his debut with Spartak Subotica during the 2001-02 season…played there till the 2003-04 championship…signed for the 2004-05 season by KK Borac Cacak…signed for the 2005-06 season by FMP Zeleznik… played there also the 2006-07 championship...moved to Spain for the 2007-08 season, signed by Girona CB. Miscellaneous: won the 2006 Adriatic League with FMP Zeleznik...won the 2007 TROPHY CASE: TICKET INFORMATION: Serbian National Cup with FMP Zeleznik...member of the Serbian National Team...played at • FIBA EuroCup: 2007 RESPONSIBLE: Cristina Buxeda the 2007 European Championship. PHONE NUMBER: +34972210100 PRESIDENT: Josep Amat FAX NUMBER: +34972223033 YEAR TEAM G 2PM/A PCT. 3PM/A PCT. FTM/A PCT. REB ST ASS BS PTS AVG VICE-PRESIDENTS: Jordi Juanhuix, Robert Mora 2001/02 Spartak S 2 1/1 100,0 1/7 14,3 1/4 25,0 2 0 1 0 6 3,0 GENERAL MANAGER: Antonio Maceiras MAIN SPONSOR: Akasvayu 2002/03 Spartak S 9 5/8 62,5 2/10 20,0 3/9 33,3 8 0 4 1 19 2,1 MANAGING DIRECTOR: Antonio Maceiras THIRD SPONSOR: Patronat Costa Brava 2003/04 Spartak S 22 6/15 40,0 1/2 50,0 2/2 100 4 2 3 0 17 0,8 TEAM MANAGER: Martí Artiga TECHNICAL SPONSOR: Austral 2004/05 Borac 26 85/143 59,4 41/110 37,3 101/118 85,6 51 57 23 1 394 15,2 FINANCIAL DIRECTOR: Victor Claveria 2005/06 Zeleznik 15 29/56 51,8 13/37 35,1 61/79 77,2 38 32 7 3 158 10,5 MEDIA: 2006/07 Zeleznik -

Slavic Idea in Political Thought of Underground Poland During World War II Idea Słowiańska W Myśli Politycznej Polski Podziemnej W Czasie II Wojny Światowej

1S[FHMŕE/BSPEPXPžDJPXZ3FWJFXPG/BUJPOBMJUJFTtOS /t World of Slavs / Świat Słowian *44/9 QSJOU t*44/ POMJOF t%0*QO Dariusz Miszewski* War Studies University, Poland / Akademia Sztuki Wojennej, Polska Slavic idea in political thought of underground Poland during World War II Idea słowiańska w myśli politycznej Polski podziemnej w czasie II wojny światowej Keywords: the Slavic idea, the Slavic nations, the Słowa kluczowe: idea słowiańska, narody sło- Polish-Soviet relations wiańskie, stosunki polsko-radzieckie During the Second World War, the Polish W czasie II wojny światowej polski rząd government put forward a plan for a new wysunął plan nowego ładu polityczne- political order in Central Europe. Its in- go w Europie Środkowej. Jej integracja tegration was to be based on the Polish- miała opierać się na federacji polsko-cze- Czechoslovak federation. Apart from the chosłowackiej. Oprócz idei federacyjnej federal idea among the groups in the oc- wśród ugrupowań w okupowanym kra- cupied country as well as in the emigra- ju, jak i na emigracji, szerzyły się idee im- tion, imperial and Slavic ideas spread as perialna i słowiańska jako ideologiczne ideological foundations of Central Euro- podstawy porządku środkowoeuropej- pean order. e Slavic idea was universal skiego. Idea słowiańska była na tyle uni- enough to exist spontaneously and as part wersalna, że występowała samoistnie oraz of the federal and imperial ideas. With- jako część idei federacyjnej i imperialnej. in them, the Slav countries were to form W ich ramach państwa słowiańskie mia- the basis for the regional integration of ły stanowić podstawę integracji regional- states between imperialist Germany and nej państw położonych między imperia- the USSR and the Baltic, Black and Adriat- listycznymi Niemcami i ZSRR oraz Mo- ic Sea. -

Memellander/Klaipėdiškiai Identity and German Lithuanian Relations

Identiteto raida. Istorija ir dabartis Vygantas Vareikis Memellander/Klaipėdiškiai Identity and German Lithuanian Relations in Lithuania Minor in the Nine teenth and Twentieth centuries Santrauka XXa. lietuviųistoriografijoje retai svarstytiKl.aipėdos krašto gyventojų(klaipėdiškių/memelende rių), turėjusių dvigubą, panašų į elzasiečių, identitetą klausimai. Paprastai šioji grnpėtapatinama su lietuviais, o klaipėdiškių identiteto reiškinys, jų politinė orientacijaXX a. pirmojepusėje aiškinami kaip aktyvios vokietinimo politikos bei lietuvių tautinės sąmonės silpnumo padariniai. Straipsnyje nagrinėjami klausimai: kaipPrūsijoje (Vokietijoje) gyvenęlietuviai, išlaikydamikalbą ir identiteto savarankiškumą, vykstant akultūracijai, perėmė vokiečių kultūros vertybes ir socialines konvencijas; kokie politiniai veiksniai formavo Prūsijos lietuvių identitetą ir kaip skirtingas Prūsijos (ir Klaipėdos krašto) lietuviškumas veikė Didžiosios Lietuvos lietuvių pažiūras. l. The history of Lithuania and Lithuania Living in a German state the Mažlietuvis was Minor began to follow divergent courses when, naturally prevailed upon to integrate into state during the Middle Ages, the Teutonic Knights political life and naturally became bilingual in conquered the tribes that dwelt on the eastern German and Lithuanian. Especially after the shores of the Baltic Sea. Lithuanians living in industrialisation and modernization of Prussia the lands governed by the Order and then by the Mažlietuvis was bilingual. This bilingualism the dukes of Prussia (after 1525) were -

Swedbalt 20-40 TL

1 Thomas Lundén draft 2018-09-02 The dream of a Balto-Scandian Federation: Sweden and the independent Baltic States 1918-1940 in geography and politics This paper will focus on the attempts by Swedish and Baltic geographers in the inter-war period to discuss a geopolitical regionalism defined by Sweden, Finland and the three Baltic States, and the political use of the so called Balto-Scandian concept1. Introduction For a long time in the 20th century, the Baltic region, or Baltikum2, here defined as the area south of the Gulf of Finland and east of the Baltic Sea, was more or less a white spot on the mental map of Swedish politicians and social scientists alike. The “inventor” of geopolitics, political scientist and conservative politician Rudolf Kjellén, urged for Swedish cultural and economic activism towards the Baltic part of Tsarist Russia (Marklund, 2014, 195-199, see also Kuldkepp, 2014, 126), but the program was never implemented, and the break-up of the Russian Empire and the new geopolitical situation, as well as Kjellén’s death in 1922, with a few exceptions put a new end to Swedish academic interests in the contemporary geopolitical situation of the area. From Eastern Baltic point of view, any super-state regionalism with Norden3 was primarily connected with Estonia, in combination with Sweden (Kuldkepp 2010, 49, 2015). Sweden and Estonia thus played a special role in the Baltic discussion about regionalism. The independence of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in 1919-1920 gave Sweden a geopolitical buffer to the neighboring great powers Russia/Soviet Union and Germany, which were initially weakened and politically unstable. -

Uefadirect #80 (12.2008)

UEFAdirect-80•E 19.11.2008 8:24 Page 1 12.08 Including Football united against racism 03 Study Group Scheme 04 General secretaries in Nyon 09 A logo for the final in Rome 10 No 58 – Février 2007 80 December 2008 UEFAdirect-80•E 19.11.2008 8:24 Page 2 Message Photos: UEFA-pjwoods.ch of the president Equal treatment for all In football as in everyday life, absolute equality is wishful thinking: there always have been and always will be some clubs with more money than others. This is not an injustice but a reality. The real injustice is that conditions are not the same for everyone and, in particular, that some clubs deliberately go into the red to reinforce their teams by means of costly transfers. Legislation is stricter in some places than others and it is clearly beyond the means of an organisation such as UEFA to interfere in national procedures. This cannot, however, be used as an excuse to do nothing. We cannot advocate respect in every possible form and champion fair play without encouraging them in the financial domain too. The first step in this direction has already been taken: by introducing IN THIS ISSUE a compulsory licence for clubs participating in European competitions, Football united UEFA has already laid down criteria to guarantee the financial health of clubs against racism 03 and, by extension, the orderly running of its competitions. Study Group Scheme 04 Our task now – and we have to make this a priority – is to refine Exhibition in Liverpool 08 the club licensing system and ensure equal treatment throughout Europe. -

The University of Chicago Smuggler States: Poland, Latvia, Estonia, and Contraband Trade Across the Soviet Frontier, 1919-1924

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SMUGGLER STATES: POLAND, LATVIA, ESTONIA, AND CONTRABAND TRADE ACROSS THE SOVIET FRONTIER, 1919-1924 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ANDREY ALEXANDER SHLYAKHTER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2020 Илюше Abstract Smuggler States: Poland, Latvia, Estonia, and Contraband Trade Across the Soviet Frontier, 1919-1924 What happens to an imperial economy after empire? How do economics, security, power, and ideology interact at the new state frontiers? Does trade always break down ideological barriers? The eastern borders of Poland, Latvia, and Estonia comprised much of the interwar Soviet state’s western frontier – the focus of Moscow’s revolutionary aspirations and security concerns. These young nations paid for their independence with the loss of the Imperial Russian market. Łódź, the “Polish Manchester,” had fashioned its textiles for Russian and Ukrainian consumers; Riga had been the Empire’s busiest commercial port; Tallinn had been one of the busiest – and Russians drank nine-tenths of the potato vodka distilled on Estonian estates. Eager to reclaim their traditional market, but stymied by the Soviet state monopoly on foreign trade and impatient with the slow grind of trade talks, these countries’ businessmen turned to the porous Soviet frontier. The dissertation reveals how, despite considerable misgivings, their governments actively abetted this traffic. The Polish and Baltic struggles to balance the heady profits of the “border trade” against a host of security concerns shaped everyday lives and government decisions on both sides of the Soviet frontier. -

Estonia Today

80 YEARS OF JUNE DEPORTATIONS 1. 80 YEARS OF JUNE DEPORTATIONS In June 1941, within one week about 95 000 people from Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Bessarabia (Moldova) were deported to the Soviet Union. This mass operation was carried out simultaneously in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia – between 14 and 17 June 1941. The operation saw the arrest of all people who were still at liberty and considered a thorn in the side of the occupying forces, mainly members of the political, military and economic elite who had been instrumental in building the independence of their states. They were taken to prison camps where most of them were executed or perished within a year. Their family members, including elderly people and children, were arrested alongside them, and they were subsequently separated and deported to the “distant regions” of the Soviet Union with extremely harsh living conditions. To cover their tracks, the authorities also sent a certain number of criminals to the camps. Prologue • As a result of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union on 23 August 1939, the Soviet Union occupied Estonia in June 1940. • Preparations for the launch of communist terror in civil society were made already before the occupation. As elsewhere, its purpose was to suppress any possible resistance of the society from the very beginning and to instil fear in people to rule out any organised resistance movement in the future. • The decision to carry out this mass operation was made at the suggestion of Soviet State Security chiefs Lavrentiy Beria and Vsevolod Merkolov in Moscow on 16 May 1941. -

Exiles and Constituents: Baltic Refugees and American Cold War Politics, 1948-1960

Exiles and Constituents: Baltic Refugees and American Cold War Politics, 1948-1960 Jonathan H. L’Hommedieu A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Turku in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Social Sciences in the Department of Contemporary History Turku 2011 Serial: Humaniora B 338 ISBN 978-951-29-4811-6 ISSN 0082-6987 Abstract Jonathan H. L’Hommedieu: Exiles and Constituents: Baltic Refugees and American Cold War Politics, 1948-1960 This dissertation explores the complicated relations between Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian postwar refugees and American foreign policymakers between 1948 and 1960. There were seemingly shared interests between the parties during the first decade of the Cold War. Generally, Eastern European refugees refused to recognize Soviet hegemony in their homelands, and American policy towards the Soviet bloc during the Truman and Eisenhower administrations sought to undermine the Kremlin’s standing in the region. More specifically, Baltic refugees and State Department officials sought to preserve the 1940 non-recognition policy towards the Soviet annexation of the Baltic States. I propose that despite the seemingly natural convergence of interests, the American experiment of constructing a State-Private network revolving around fostering relations with exile groups was fraught with difficulties. These difficulties ultimately undermined any ability that the United States might have had to liberate the Baltic States from the Soviet Union. As this dissertation demonstrates, Baltic exiles were primarily concerned with preserving a high level of political continuity to the interwar republics under the assumption that they would be able to regain their positions in liberated, democratic societies. -

European Regions and Boundaries European Conceptual History

European Regions and Boundaries European Conceptual History Editorial Board: Michael Freeden, University of Oxford Diana Mishkova, Center for Advanced Study Sofi a Javier Fernández Sebastián, Universidad del País Vasco, Bilbao Willibald Steinmetz, University of Bielefeld Henrik Stenius, University of Helsinki The transformation of social and political concepts is central to understand- ing the histories of societies. This series focuses on the notable values and terminology that have developed throughout European history, exploring key concepts such as parliamentarianism, democracy, civilization, and liberalism to illuminate a vocabulary that has helped to shape the modern world. Parliament and Parliamentarism: A Comparative History of a European Concept Edited by Pasi Ihalainen, Cornelia Ilie and Kari Palonen Conceptual History in the European Space Edited by Willibald Steinmetz, Michael Freeden, and Javier Fernández Sebastián European Regions and Boundaries: A Conceptual History Edited by Diana Mishkova and Balázs Trencsényi European Regions and Boundaries A Conceptual History ላሌ Edited by Diana Mishkova and Balázs Trencsényi berghahn N E W Y O R K • O X F O R D www.berghahnbooks.com Published in 2017 by Berghahn Books www.berghahnbooks.com © 2017 Diana Mishkova and Balázs Trencsényi All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Mishkova, Diana, 1958– editor. | Trencsenyi, Balazs, 1973– editor. -

University of Latvia

Latvian Folklore and Literature Course code: Folk4012 Credit points: 2 ECTS: 3 Course developer: Dr. Raimonds Auskaps Course abstract The course is designed to provide students with the basic background information for reading and analysing Latvian literature. Each author and each work is placed in its historical context. The course follows up the development of Latvian literature starting from its very origins in Latvian folklore, through National Awakening, during the Republic of Latvia between the two world wars, during the Soviet occupation, to contemporary writing. The course consists of lectures and discussions, paying attention to the most significant periods and authors. The students read and discuss the works of Latvian literature translated into English, linking the respective material with Latvian mentality and the concrete historical period. Results During the course, the students are supposed to acquire basic facts about Latvian folklore and literature, develop the skill to analyse works of literature. Course description-general outline 1. The Concept and Subdivision of Folklore. Latvian Poetic Folklore, its Genres. Dainas. 2. Narrative Folklore. Brachylogisms. Latvian Mythology. 3. National Awakening of 19th c. New Latvians. J.Alunāns. Brothers Kaudzīte. “The Time of Land-surveyors”. A.Pumpurs. “Lāčplēsis”. 4. Romantic Poetry of Auseklis. Apsīšu Jēkabs. “Rich Relatives”. Creative work of A.Brigadere. 5. Creative work of R.Blaumanis. Creative work of Aspazija, Creative work of Rainis. 6. Innovative poetry of E.Veidenbaums. Creative work of J.Jaunsudrabiņš. Creative work of J.Poruks. Creative work of V.Plūdons. 7. Creative work of A.Upīts. Fairy-tales of K.Skalbe. E.Virza. “Straumēni”. Stories of J.Ezeriņš. -

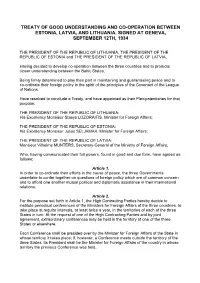

Treaty of Good Understanding and Co-Operation Between Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania

TREATY OF GOOD UNDERSTANDING AND CO-OPERATION BETWEEN ESTONIA, LATVIA, AND LITHUANIA. SIGNED AT GENEVA, SEPTEMBER 12TH, 1934 THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA, THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF ESTONIA and THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LATVIA, Having decided to develop co-operation between the three countries and to promote closer understanding between the Baltic States, Being firmly determined to play their part in maintaining and guaranteeing peace and to co-ordinate their foreign policy in the spirit of the principles of the Covenant of the League of Nations, Have resolved to conclude a Treaty, and have appointed as their Plenipotentiaries for that purpose: THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA: His Excellency Monsieur Stasys LOZORAITIS, Minister for Foreign Affairs; THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF ESTONIA: His Excellency Monsieur Julius SELJAMAA, Minister for Foreign Affairs; THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LATVIA: Monsieur Vilhelms MUNTERS, Secretary-General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Who, having communicated their full powers, found in good and due form, have agreed as follows: Article 1. In order to co-ordinate their efforts in the cause of peace, the three Governments undertake to confer together on questions of foreign policy which are of common concern and to afford one another mutual political and diplomatic assistance in their international relations. Article 2. For the purpose set forth in Article 1, the High Contracting Parties hereby decide to institute periodical conferences of the Ministers for Foreign Affairs of the three countries, to take place at regular intervals, at least twice a year, in the territories of each of the three States in turn. -

Apprenticeship, Partnership, Membership: Twenty Years of Defence Development in the Baltic States

Apprenticeship, Partnership, Membership: Twenty Years of Defence Development in the Baltic States Edited by Tony Lawrence Tomas Jermalavičius 1 Apprenticeship, Partnership, Membership: Twenty Years of Defence Development in the Baltic States Edited by Tony Lawrence Tomas Jermalavičius International Centre for Defence Studies Toom-Rüütli 12-6 Tallinn 10130 Estonia Apprenticeship, Partnership, Membership: Twenty Years of Defence Development in the Baltic States Edited by Tony Lawrence Tomas Jermalavičius © International Centre for Defence Studies Tallinn, 2013 ISBN: 978-9949-9174-7-1 ISBN: 978-9949-9174-9-5 (PDF) ISBN: 978-9949-9174-8-8 (e-pub) ISBN 978-9949-9448-0-4 (Kindle) Design: Kristjan Mändmaa Layout and cover design: Moonika Maidre Printed: Print House OÜ Cover photograph: Flag dedication ceremony of the Baltic Peacekeeping Battalion, Ādaži, Latvia, January 1995. Courtesy of Kalev Koidumäe. Contents 5 Foreword 7 About the Contributors 9 Introduction Tomas Jermalavičius and Tony Lawrence 13 The Evolution of Baltic Security and Defence Strategies Erik Männik 45 The Baltic Quest to the West: From Total Defence to ‘Smart Defence’ (and Back?) Kęstutis Paulauskas 85 The Development of Military Cultures Holger Mölder 122 Supreme Command and Control of the Armed Forces: the Roles of Presidents, Parliaments, Governments, Ministries of Defence and Chiefs of Defence Sintija Oškalne 168 Financing Defence Kristīne Rudzīte-Stejskala 202 Participation in International Military Operations Piret Paljak 240 Baltic Military Cooperative Projects: a Record of Success Pete Ito 276 Conclusions Tony Lawrence and Tomas Jermalavičius 4 General Sir Garry Johnson Foreword The swift and total collapse of the Soviet Union may still be viewed by some in Russia as a disaster, but to those released from foreign dominance it brought freedom, hope, and a new awakening.