Citation by Professor Mary E Daly, UCD School of History And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inter-Departmental Committee Interim Progress Report

Inter-Departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalen Laundries Chaired by Senator Martin McAleese Interim Progress Report I. Background A. Establishment B. Membership II. Terminology and overall approach of the Committee III. Mandate of the Committee A. Institutions B. Dates C. Nature of the mandate: fact-finding role IV. Procedures of the Committee A. General procedures B. Data protection and confidentiality C. Archive of the Committee‟s work V. Activities and progress to date A. Meetings of the Committee and cooperation by Departments and State agencies B. Cooperation with the relevant Religious Orders C. Cooperation with relevant expert agencies and academic experts D. Cooperation with relevant advocacy and/or representative groups (including submissions from former residents) VI. Intended timeline for Final Report 1 I. Background A. Establishment 1. The Inter-Departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalen Laundries (“the Committee”) was established pursuant to a Government decision in June 2011. At that time, Government decided the Committee should be chaired by an independent person. It tasked the Committee with a function of establishing the facts of State involvement with the Magdalen Laundries and producing a narrative report thereon. An initial report on progress was requested within 3 months of commencement of the Committee‟s work. 2. It was decided that, in addition to the independent Chair, the Committee should be composed of representatives of six Government Departments, as follows: Department of Justice and Equality; Department of Health; Department of Environment, Community and Local Government; Department of Education and Skills; Department of Jobs, Enterprise and Innovation; and Department of Children & Youth Affairs. -

A Sunny Day in Sligo

June 2009 VOL. 20 #6 $1.50 Boston’s hometown journal of Irish culture. Worldwide at bostonirish.com All contents copyright © 2009 Boston Neighborhood News, Inc. Picture of Grace: A Sunny Day in Sligo The beauty of the Irish landscape, in this case, Glencar Lough in Sligo at the Leitrim border, jumps off the page in this photograph by Carsten Krieger, an image taken from her new book, “The West of Ireland.” Photo courtesy Man-made Images, Donegal. In Charge at the BPL Madame President and Mr. Mayor Amy Ryan is the multi- tasking president of the venerable Boston Pub- lic Library — the first woman president in the institution’s 151-year his- tory — and she has set a course for the library to serve the educational and cultural needs of Boston and provide access to some of the world’s most historic records, all in an economy of dramatic budget cuts and a significant rise in library use. Greg O’Brien profile, Page 6 Nine Miles of Irishness On Old Cape Cod, the nine-mile stretch along Route 28 from Hyannis to Harwich is fast becom- ing more like Galway or Kerry than the Cape of legend from years ago. This high-traffic run of roadway is dominated by Irish flags, Irish pubs, Irish restaurants, Irish hotels, and one of the fast- est-growing private Irish Ireland President Mary McAleese visited Boston last month and was welcomed to the city by Boston clubs in America. Mayor Tom Menino. Also pictured at the May 26 Parkman House event were the president’s husband, BIR columnist Joe Dr. -

Seanad Éireann

Vol. 220 Tuesday, No. 9 5 February 2013 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SEANAD ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Business of Seanad 646 Resignation of Member 647 Order of Business 649 Planning and Development (Planning Enforcement) General Policy Directive 2013: Motion ����������������������������666 Criminal Justice (Spent Convictions) Bill 2012: Report and Final Stages 666 Order of Business: Motion 677 Adjournment Matters ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������682 05/02/2013GG01100Garda Stations Refurbishment ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������682 05/02/2013HH00500Visa Applications 684 05/02/2013JJ00300Water and Sewerage Schemes ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������686 05/02/2013KK00400Sale of State Assets 689 SEANAD ÉIREANN Dé Máirt, 05 Feabhra 2013 Tuesday, 05 February 2013 Chuaigh an Cathaoirleach i gceannas ar 230 pm Machnamh -

News Ministers and Secretaries Bill 2011 to Establish New Department

News Ministers and Secretaries Bill 2011 to establish new Department The Minister for Public Expenditure and Reform, Brendan Howlin TD, has published the Ministers and Secretaries (Amendment) Bill 2011. This Bill provides the legislative basis which will allow for the formal establishment of Department for Public Expenditure and Reform. The Bill facilitates the transfer of certain functions from the Minister of Finance to the Minister for Public Expenditure and Reform specifically all functions relating to the public service. Public service reform functions, including modernisation functions will also be placed on a statutory footing. Responsibility for managing public expenditure will also be transferred to the new Department including the management of gross voted expenditure and the annual estimates process. The Department will also be allocated general sanctioning powers in relation to expenditure and policy matters. The minister for finance will retain responsibility for budgetary parameters. A number of the offices currently under the remit of the Department of Finance will also be moved to the new Department including the Valuation Office, State Laboratory, Commissioners of Public Works, Public Appointments Service and the Commission for Public Service Appointments. The new Department will also take over modernisation, development and reform functions. The Minister stated that he hoped the “legislation will be given priority status in its passage through the Oireachtas.” The mission statement on the new Departments newly created website outlines its goals as being “to achieve the Government’s social and economic goals by ensuring the effective management of taxpayers’ money and the delivery of quality public services that meet the needs of citizens”. -

The Magdalene Laundries

Ireland’s Silences: the Magdalene Laundries By Nathalie Sebbane Thanks to the success of Peter Mullan’s film The Magdalene Sisters, Magdalene laundries—institutions meant to punish Ireland’s “fallen” women—are now part of the country’s collective memory. Despite tremendous social advances, survivors still await reparation and an official apology. In 2016, the centenary of the 1916 Easter Rising was commemorated with great fanfare, but another anniversary went almost unnoticed. Yet it was on September 25, 1996, that Ireland’s last remaining Magdalene laundry closed its doors. These institutions, made infamous by Peter Mullan’s 2003 feature film, The Magdalene Sisters, are now part of Ireland’s collective memory. But what memory is this? And what Ireland does it relate to? It is estimated that since the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922, around 10,000 girls and women were referred to these institutions, staying there from a month up to several decades. Magdalene laundries however, had been in existence in Ireland since the 18th century under other guises and other names. Their origin can even be traced to 13th-century Italy. Yet at a time when Ireland is looking to redefine its national identity and fully embrace modernity with the legalisation of same-sex marriage in 2015 and the repeal of the 8th amendment on abortion on May 25, 2018, it seems relevant to commemorate the closure of the last laundry and revisit the history of Magdalene laundries. Though they were not an Irish invention strictly speaking, they remain one of the key elements of what historian James Smith has called “Ireland’s architecture of containment”—a system which erases vulnerable groups destined to ‘disappear’ in Irish society, whether in Magdalene laundries, Industrial Schools or Mother and Baby Homes. -

State Involvement in the Magdalene Laundries

This redacted version is being made available for public circulation with permission from those who submitted their testimonies State involvement in the Magdalene Laundries JFM’s principal submissions to the Inter-departmental Committee to establish the facts of State involvement with the Magdalene Laundries Compiled by1: Dr James M. Smith, Boston College & JFM Advisory Committee Member Maeve O’Rourke, JFM Advisory Committee Member 2 Raymond Hill, Barrister Claire McGettrick, JFM Co-ordinating Committee Member With Additional Input From: Dr Katherine O’Donnell, UCD & JFM Advisory Committee Member Mari Steed, JFM Co-ordinating Committee Member 16th February 2013 (originally circulated to TDs on 18th September 2012) 1. Justice for Magdalenes (JFM) is a non-profit, all-volunteer organisation which seeks to respectfully promote equality and advocate for justice and support for the women formerly incarcerated in Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries. Many of JFM’s members are women who were in Magdalene Laundries, and its core coordinating committee, which has been working on this issue in an advocacy capacity for over twelve years, includes several daughters of women who were in Magdalene Laundries, some of whom are also adoption rights activists. JFM also has a very active advisory committee, comprised of academics, legal scholars, politicians, and survivors of child abuse. 1 The named compilers assert their right to be considered authors for the purposes of the Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000. Please do not reproduce without permission from JFM (e-mail: [email protected]). 2 Of the Bar of England and Wales © JFM 2012 Acknowledgements Justice for Magdalenes (JFM) gratefully acknowledges The Ireland Fund of Great Britain for its recent grant. -

President's Annual Report

President’s Annual Report October 2015 to September 2016 www.dcu.ie Contents President’s Introduction .................................. 3 DCU’s Expanding Horizons ............................... 5 Healthy Progress ............................................. 8 Ireland’s First Faculty of Education...................10 Women in Leadership ..................................... 12 Remembering 1916.......................................... 15 A University of Enterprise ............................... 17 University Financial Report .............................19 Governing Authority Attendance ...................... 21 Annual Report || October October 2015 2015 – – September September 2016 2016 President’s Introduction The past 12 months have been truly historic for Dublin City University. We have marked the conclusion of the incorporation process. Now the real work begins. Incorporation has allowed for a major expansion in student numbers. Alongside the expansion of the student population, DCU now has three academic campuses in the Glasnevin-Drumcondra area, making it Ireland’s fastest growing university. Drawing on the proud traditions of St Patrick’s College, the Mater Dei Institute and the Church of Ireland College of Education, we have established Ireland’s first faculty of Education, The DCU Institute of Education. Indeed, with more than 120 full-time academics and a cohort of nearly 4,000 students, it is now one of Europe’s largest Education faculties. This report captures not only DCU’s strength in the field of Education, but also features a sample of our innovation and excellence in other disciplines, research areas and activities. In the realm of Human Health, the report provides examples of the University’s leadership in addressing a range of important challenges such as dementia, sight loss and cardiovascular disease. You will also see that our innovation campus DCU Alpha is creating exciting new solutions to a range of societal issues, over the past 12 months. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2011 Remarks at Trinity College Dublin

Administration of Barack Obama, 2011 Remarks at Trinity College Dublin in Dublin, Ireland May 23, 2011 The President. Thank you! Hello, Dublin! Hello, Ireland! My name is Barack Obama— [applause]—of the Moneygall Obamas. And I've come home to find the apostrophe that we lost somewhere along the way. [Laughter] Audience member. I've got it here! The President. Now—is that where it is? [Laughter] Some wise Irish man or woman once said that broken Irish is better than clever English. So here goes: Ta athas orm a bheith in Eirinn—I am happy to be in Ireland! I'm happy to be with so many a chairde. I want to thank my extraordinary hosts—first of all, Taoiseach Kenny, his lovely wife Fionnuala, President McAleese, and her husband Martin—for welcoming me earlier today. Thank you, Lord Mayor Gerry Breen and the Garda for allowing me to crash this celebration. Let me also express my condolences on the recent passing of former Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald, someone who believed in the power of education; someone who believed in the potential of youth; most of all, someone who believed in the potential of peace and who lived to see that peace realized. And most of all, thank you to the citizens of Dublin and the people of Ireland for the warm and generous hospitality that you've shown me and Michelle. It certainly feels like 100,000 welcomes. We feel very much at home. I feel even more at home after that pint that I had. [Laughter] Feel even warmer. -

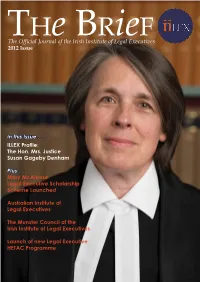

The Brief 2012 | IILEX 1 in the Public Service

H R F TThe OfficialTThe OfficialH Journal Journale ofe the of IrishtheB IrishB Institute InstituteR of ie Legalof ieLegal Executives ExecutivesF 2011 Issue2012 Issue IN THiS ISSue... IILEX PROFILE: The new Minister for Justice, Equality and Defence; MR ALAN SHATTER TD Plus... In this Issue . RememberingILLEX Profile: ChristineThe Hon. Mrs. Smith Justice Susan Gageby Denham The Office of Notary Public Plus . in IrelandMary McAleese Legal Executive Scholarship A HistoryScheme Launched of the Women’s RefugeAustralian in Institute Rathmines of Legal Executives SpotlightThe Munster on Council Cork ofCity the HallIrish Institute of Legal Executives Launch of new Legal Executive ElementsHETAC Programme of Pro-active Criminal Justice A Day in the Life of a Legal Executive The Brief 2012 | IILEX 1 in the Public Service 2011 Brief.indd 1 13/08/2011 10:41:35 THe BRieF 2012 ISSUE The OfficialH Journale of the Irish InstituteCONTR of EieLegalNTS ExecutivesF T B Page Page 2011 Issue Message from the President 3 Irish Towns in Capetown, South Africa 11 Profile on The Hon. Mrs. 4 Australian Institute of Legal Executives 12 IN T HiSJustice ISS Susanue Gageby... Denham John Lonergan - ‘The Governor’ 14 Mary McAleese 5 Conferring Ceremony at 16 IILEX PROFILE:Legal Executive Scholarship Scheme Griffith College Dublin The newBook ReviewMinister - Bram Stokers’for Dracula 6 Munster Council of IILEX 17 Justice,The BurrenEquality Law Schooland 7 Report on a Paper written by the 18 Honourable Mr.Justice Frank Clarke, Irish Law Awards 2012 7 Defence; Supreme Court Top Tips for Marketing Yourself 8 MR ALAN SHATTER TD Remembering Michael Doyle FIILEX 20 Fellowships Presented to Members 9 Plus.. -

Études Irlandaises, 37-2

Études irlandaises 37-2 | 2012 Enjeux féministes et féminins dans la société irlandaise contemporaine Feminist and women's issues in contemporary Irish society Fiona McCann et Nathalie Sebbane (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/3108 DOI : 10.4000/etudesirlandaises.3108 ISSN : 2259-8863 Éditeur Presses universitaires de Caen Édition imprimée Date de publication : 30 octobre 2012 ISBN : 978-7535-2158-2 ISSN : 0183-973X Référence électronique Fiona McCann et Nathalie Sebbane (dir.), Études irlandaises, 37-2 | 2012, « Enjeux féministes et féminins dans la société irlandaise contemporaine » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 30 octobre 2014, consulté le 16 mars 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/3108 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/etudesirlandaises.3108 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 mars 2020. Études irlandaises est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d’Utilisation Commerciale - Partage dans les Mêmes Conditions 4.0 International. 1 SOMMAIRE Hommage Catherine Maignant Introduction Fiona McCann et Nathalie Sebbane Études d'histoire et de civilisation Women of Ireland, from economic prosperity to austere times: who cares? Marie-Jeanne Da Col Richert Gender and Electoral Representation in Ireland Claire McGing et Timothy J. White The condition of female laundry workers in Ireland 1922-1996: A case of labour camps on trial Eva Urban Ireland’s criminal conversations Diane Urquhart Art et image Women’s art in Ireland -

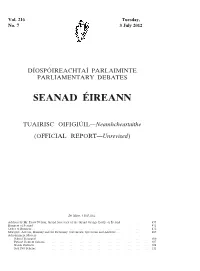

Seanad Éireann

Vol. 216 Tuesday, No. 7 3 July 2012 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SEANAD ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Dé Máirt, 3 Iúil 2012. Address by Mr. Drew Nelson, Grand Secretary of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland … … … 455 Business of Seanad ………………………………471 Order of Business …………………………………472 Mortgage Arrears, Banking and the Economy: Statements, Questions and Answers …………483 Adjournment Matters School Transport ………………………………506 Patient Redress Scheme ……………………………507 Garda Districts ………………………………508 Sick Pay Scheme ………………………………511 SEANAD ÉIREANN ———— Dé Máirt, 3 Iúil 2012. Tuesday, 3 July 2012. ———— Chuaigh an Cathaoirleach i gceannas ar 12.00 p.m. ———— Machnamh agus Paidir. Reflection and Prayer. ———— Address by Mr. Drew Nelson, Grand Secretary of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland An Cathaoirleach: I acknowledge the presence in the House of the British and American ambassadors. On behalf of my fellow Senators, I am delighted to welcome to the House Mr. Drew Nelson, grand secretary of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland, and the accompanying delegation led by the grand master, Mr. Edward Stevenson. Before we begin, I would like to make a few personal remarks. I have been a public representative in various capacities since 1979. I have many memories from those 33 years of significant events. However, on this historic day, I cannot help but reflect back on what I knew or, maybe more accurately, what I thought I knew about the Orange Order until very recently. In this regard, I am sure I am no different from the other Members of this House. My own background is typical of many with a rural Irish upbringing. -

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 759 Wednesday, No. 2 14 March 2012 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Dé Céadaoin, 14 Márta 2012. Leaders’ Questions ……………………………… 399 Order of Business ……………………………… 406 Visit of United States of America Delegation …………………… 416 Order of Business (resumed)……………………………417 Freedom of Information (Amendment) Bill 2012: First Stage ……………… 422 Local Government (Superannuation) (Consolidation) Scheme 1998 (Amendment) Bill 2012: First Stage 422 Comptroller and Auditor General (Amendment) Bill 2012: First Stage …………… 423 Motor Vehicle (Duties and Licenses) Bill 2012: Financial Resolution …………… 423 Clotting Factor Concentrates and Other Biological Products Bill 2012: Order for Second Stage …………………………… 423 Second Stage ……………………………… 423 Ceisteanna — Questions Minister for Defence Priority Questions …………………………… 441 Other Questions …………………………… 451 Topical Issue Matters ……………………………… 466 Topical Issue Debate Broadcasting Legislation …………………………… 467 Post Office Network …………………………… 468 Community Care ……………………………… 472 Hospital Services ……………………………… 475 Clotting Factor Concentrates and Other Biological Products Bill 2012: Second Stage (resumed) and Subsequent Stages……………………………… 477 Criminal Justice (Female Genital Mutilation) Bill 2011: Order for Report Stage …………………………… 490 Report and Final Stages …………………………… 490 Motor Vehicle (Duties and Licenses) Bill 2012: Message from Select Sub-Committee ……………………… 505 Private Members’ Business Banking Sector Regulation: Motion (resumed)……………………505 Questions: Written Answers …………………………… 537 DÁIL ÉIREANN ———— Dé Céadaoin, 14 Márta 2012. Wednesday, 14 March 2012. ———— Chuaigh an Ceann Comhairle i gceannas ar 10.30 a.m. ———— Paidir. Prayer. ———— Leaders’ Questions Deputy Micheál Martin: In the past few weeks there have, to say the least, been mixed messages from the Government in regard to Ireland’s obligations on the promissory note issue. As the Taoiseach knows, the promissory note mechanism was created and agreed as banks were not allowed to fail.