Mirror, Mirror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Withering Heights

Withering Heights When one mentions the Presbyterian Church, the name that first comes to mind is that of the Scottish Calvinist clergyman John Knox. This dynamic religious leader of the Protestant Reformation founded the Presbyterian denomination and was at the beginning of his ministry in Edinburgh when he lost his beloved wife Marjorie Bowes. In 1564 he married again, but the marriage received a great deal of attention. This was because she was remotely connected with the royal family, and Knox was almost three times the age of this young lady of only seventeen years. She was Margaret Stewart, daughter of Andrew Stewart, 2nd Lord of Ochiltree. She bore Knox three daughters, of whom Elizabeth became the wife of John Welsh, the famous minister of Ayr. Their daughter Lucy married another clergyman, the Reverend James Alexander Witherspoon. Their descendant, John Knox Witherspoon (son of another Reverend James Alexander Witherspoon), signed the Declaration of Independence on behalf of New Jersey and (in keeping with family tradition) was also a minister, in fact the only minister to sign the historic document. John Knox Witherspoon (1723 – 1794), clergyman, Princeton’s sixth president and signer of the Declaration of Independence. Just like Declaration of Independence signatory John Witherspoon, actress Reese Witherspoon is also descended from Reverend James Alexander Witherspoon and his wife Lucy (and therefore John Knox). The future Academy Award winner, born Laura Jeanne Reese Witherspoon, was born in New Orleans, having made her début appearance at Southern Baptist Hospital on March 22, 1976. New Orleans born Academy Award winning actress, Reese Witherspoon Reese did not get to play Emily Brontë’s Cathy in “Wuthering Heights” but she did portray Becky Sharp in Thackeray’s “Vanity Fair”. -

Legally Blonde: Introduction

Being true to yourself never goes out of style! WINNER BEST NEW MUSICAL 2011 OLIVIER AWARD EDUCATION KIT AUSTRALIAN PREMIERE SEASON • SYDNEY LYRIC LegallyBlonde.com.au facebook.com/ legallyblondemusical @legallyblondeoz Legally Blonde: INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION This teacher’s guide has been developed as a teaching tool to assist teachers who are bringing their students to see the show. This guide is based on Camp Broadway’s StageNOTES, conceived for the original Broadway musical adaptation of Amanda Brown’s 2001 novel and the film released that same year, and has been adapted for use within the UK and Australia. The Australian Education Pack is intended to offer some pathways into the production, and focuses on some of the topics covered in Legally Blonde which may interest students and teachers. It is not an exhaustive analysis of the musical or the production, but instead aims to offer a variety of stimuli for debate, discussion and practical exploration. It is anticipated that the Education Pack will be best utilised after a group of students have seen the production with their teacher, and can engage in an informed discussion based on a sound awareness of the musical. We hope that the information provided here will both enhance the live theatre experience and provide readers with information they may not otherwise have been able to access. Legally Blonde is an uplifting, energising, feel-good show and with that in mind we hope this pack will be enjoyed through equally energising and enjoyable practical work in the classroom and drama studio. 1 Legally Blonde: INTRODUCTION LEgally Blonde Education Pack CONTENTS PAGE INTODUCTION 1. -

Director's Notes

DIRECTOR’S NOTES Thoughts on LEGALLY BLONDE The musical Legally Blonde is based on a novel by Amanda Brown and the 2001 film of the same name directed by Robert Luketic. The film was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture: Musical or Comedy and ranks 29th on Bravo’s 2007 list of “100 Funniest Movies.” Premiering on January 23, 2007 in San Francisco, the Broadway musical version of Legally Blonde opened in NYC at the Palace Theatre on April 29, 2007. The show’s stars, Laura Bell Bundy, Christian Borle, and Orfeh were all nominated for Tony Awards. Later, the Broadway show was the focus of an MTV reality TV series called “Legally Blonde – The Musical: The Search for Elle Woods,” in which the winner would take over the role of Elle on Broadway. The Broadway show closed on October 19, 2008 after 595 performances. But even more successful than the Broadway run of Legally Blonde, was a highly lauded 3 year run at the Savoy Theatre in London’s West End, in which the show was nominated for five Laurence Olivier Awards. It won three, including Best New Musical. Since then, Legally Blonde has enjoyed international success in productions seen in South Korea, The Netherlands, France, The Philippines, Sweden, and Finland. Certainly, it is undeniable that both film and musical are pure escapist joy. But Legally Blonde does have a point beyond its camp wondrousness – and that is to challenge the way people make assumptions about appearance. For whether you are a beautiful bubbly blonde (like our heroine, Elle) or someone more “serious” in nature, we all have had to, at one time or another, battle prejudice against ourselves. -

Legally Blonde Cast List

Legally Blonde Cast List Elle Woods………………………………………………………………………………….Kaylie Tuttle/Greer King Emmett Forrester……………………………………...……………………………………………….Jordan Pogue Paulette Bonafonte’………………………………………………………………………..….…..…….Skyler Ward Warner Huntington III…………………..………………………………………………….….……Brittin Sullivan Brooke Wyndham………………………………………………………………………………….………Avery Bruce Professor Callahan…………………………..……………………………………………………….……Sam Gibson Vivienne Kensington……………………………………………………….………………………..Elizabeth Ring Margot………………………………………………………………….……….………….……….Brooklyn Jennings Serena…………………………………………….……………………………………….………………….Natalie Way Pilar…………….………………………………….…..……………………….………Sarah Mitchell/Kelsey Drees Kate…………………………………………………......…….………………………….…………………Nicole Vincent Gaelen…………………………………………..……………………………………………………….Bailey Weathers Tiffany………………………………………..…………………………………………………………………Rainey Ross Courtney…………………………………..……………………………………………………………..Mikee Olegario Sandi…………………………………………..………………………………………………………………..Payton King Angel…………………………………………….………………………….…………………….…………Lizzie Schaefer Enid……………………………………………...……………………………………………………………..Lauren Black Mr. Woods……………………………………..………………………………………………………….David Nichols Mrs. Woods………………………………….……………………..………………………………….Emily Freeman Chutney Wyndham…………………………...………………………………………………………Bethie Butera Kyle……………………………………....……………………………………………………………………Harris Sutton Winthrop………………………………………..………………………………………………………Lane Burchfield Judge……………………………………………………………………………………….……….Autumne Kendricks Grandmaster Chad…………………………………………………………………..……………………..DJ Boswell Dewey……………………………………………………..…….………………………..Easton -

Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 11 (2004-2005) Issue 2 William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law: Symposium: Attrition of Women from Article 6 the Legal Profession February 2005 Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys Ann Bartow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Law and Gender Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Repository Citation Ann Bartow, Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys, 11 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 221 (2005), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/ wmjowl/vol11/iss2/6 Copyright c 2005 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl SOME DUMB GIRL SYNDROME: CHALLENGING AND SUBVERTING DESTRUCTIVE STEREOTYPES OF FEMALE ATTORNEYS ANN BARTOW* I. INTRODUCTION Almost every woman has had the experience of being trivialized, regarded as if she is just 'some dumb girl,' of whom few productive accomplishments can be expected. When viewed simply as 'some dumb girls,' women are treated dismissively, as if their thoughts or contributions are unlikely to be of value and are unworthy of consideration. 'Some Dumb Girl Syndrome' can arise in deeply personal spheres. A friend once described an instance of this phenomenon: When a hurricane threatened her coastal community, her husband, a military pilot, was ordered to fly his airplane to a base in the Midwest, far from the destructive reach of the impending storm. This left her alone with their two small children. -

CANDY L. WALKEN Hair Design/Stylist IATSE 706

CANDY L. WALKEN Hair Design/Stylist IATSE 706 FILM UNTITLED DAVID CHASE PROJECT Department Head, Los Angeles Aka TWYLIGHT ZONES Director: David Chase THE BACK-UP PLAN Department Head Director: Alan Poul Cast: Alex O’Loughlin, Melissa McCarthy, Michaela Watkins NAILED Department Head Director: David O. Russell Cast: Jessica Biel, Jake Gyllenhaal, Catherine Keener, James Marsden THE MAIDEN HEIST Department Head Director: Peter Hewitt Cast: Christopher Walken, Marcia Gay Harden, William H. Macy THE HOUSE BUNNY Hair Designer/Department Head Personal Hair Stylist to Anna Faris Director: Fred Wolf Cast: Emma Stone, Kat Dennings, Katharine McPhee, Rumer Willis DISTURBIA Department Head Director: D.J. Caruso Cast: Shia LaBeouf, Carrie-Anne Moss, David Morse, Aaron Yoo FREEDOM WRITERS Department Head Director: Richard La Gravenese Cast: Imelda Staunton, Scott Glenn, Robert Wisdom MUST LOVE DOGS Personal Hair Stylist to Diane Lane Director: Gary David Goldberg A LOT LIKE LOVE Department Head Director: Nigel Cole Cast: Ashton Kutcher, Amanda Peet CELLULAR Personal Hair Stylist to Kim Basinger Director: David R. Ellis ELVIS HAS LEFT THE BUILDING Personal Hair Stylist to Kim Basinger Director: Joel Zwick UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN Personal Hair Stylist to Diane Lane Director: Audrey Wells THE MILTON AGENCY Candy L. Walken 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 3 SUSPECT ZERO Department Head Director: Elias Merhige Cast: Aaron -

Sexual Music Videos (E.G., Zhang Et Al., 2008), Thin-Ideal Television (E.G., Harrison, 2000) and Violent Television (E.G., Huesmann, Moise, & Podolski, 1997)

EXPOSURE TO SEXUAL MEDIA AND COLLEGE STUDENTS’ SEXUAL RISK-TAKING AND SEXUAL REGRET BY YUANYUAN ZHANG DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kristen Harrison, Chair Professor David Tewksbury, Director of Research Professor Barbara J. Wilson Professor Travis L. Dixon, University of California, Los Angeles Abstract Sexual risk-taking represents a significant health problem among college students. Although media may play an important role in college students’ sexual risk-taking, research in this area has been sparse. Using social cognitive theory as the theoretical framework, this dissertation aimed to achieve three goals. First, the study sought to examine how exposure to sexual content in six media (i.e., television, songs, music videos, movies watched at home, movies watched in the theater, and magazines) might be related to college students’ sexual risk-taking. Second, the study investigated a list of moderators that might influence the relationship between media exposure and sexual risk-taking. Five moderators (i.e., gender [femaleness], race [whiteness], sensation seeking, positive premarital sexual attitudes, and endorsement of the sexual double standard) were proposed to strengthen the relationship, and three moderators (i.e., school performance, religiosity, and parental monitoring) were proposed to weaken the relationship. Lastly, the study explored whether sexual media exposure may be linked to sexual regret indirectly through its effect on sexual risk-taking. The main project was an online survey completed by 561college students. To assist the investigation, three subprojects were conducted beforehand. -

New Year, New Colloquia Jammah Club Jams Lunchroom

Page 15 Page 7 Insight on Mens Cross Jerry Wang’s Country gets a Northside head start experience eat New year, new colloquia This year’s colloquium theme by Krystn Collins B As a new year at Northside commences and students begin settling into their classes, so initiates another year of colloquium, one of the things that sets the school apart from many others. “Colloquium offers a wealth of experiences,” Mr. Barry Rodg- ers, Northside’s principal, said on Northside College Preparatory High School October 2008 the school’s website. “Through participation in colloquium we transcend apparent limitations and explore new areas of learning oof that go beyond our own perceived limitations.” But what exactly does tran- scending limitations and exploring new areas of learning mean for the Vol. 10 No. 2 Vol. students of this year? Last year, the theme was a World of Possibilities, in which Northsiders were encouraged to H participate in various activities that culminated in the school-wide colloquia; these events emphasized global magnificence and world culture as aspects that bring people together instead of differences that force them apart. This year the theme is Ameri- can Tapestry: Sharing Our US Experience. “This year’s theme,” Ms. Lauren Krischer, Adv. 902, and Julia Reeves, Adv. 903, work hard as the learn the art of sewing, Susan Spillane, Director of Special knitting and embriodery in the colloquium “A Stich in Time Saves Nine.” Programs, said, “is a way to share Photo by Alejandro Valdivieso our own stories of living here in the United States. We will be weav- Calligraphy stand out, but unfa- be encouraged to share what they opportunities available to all as ing together experiences via music miliar ones, too, have made their personally have to offer in the way the American Tapestry is woven and storytelling to examine and debut, such as The Dragon Comes of living in the United States as skillfully together by students and contribute to our rich and colorful to America and Political Junkie. -

1 Production Information in Just Go with It, a Plastic Surgeon

Production Information In Just Go With It, a plastic surgeon, romancing a much younger schoolteacher, enlists his loyal assistant to pretend to be his soon to be ex-wife, in order to cover up a careless lie. When more lies backfire, the assistant's kids become involved, and everyone heads off for a weekend in Hawaii that will change all their lives. Columbia Pictures presents a Happy Madison production, Just Go With It. Starring Adam Sandler and Jennifer Aniston. Directed by Dennis Dugan. Produced by Adam Sandler, Jack Giarraputo, and Heather Parry. Screenplay by Allan Loeb and Timothy Dowling. Based on ―Cactus Flower,‖ Screenplay by I.A.L. Diamond, Stage Play by Abe Burrows, Based upon a French Play by Barillet and Gredy. Executive Producers are Barry Bernardi, Allen Covert, Tim Herlihy, and Steve Koren. Director of Photography is Theo Van de Sande, ASC. Production Designer is Perry Andelin Blake. Editor is Tom Costain. Costume Designer is Ellen Lutter. Music by Rupert Gregson-Williams. Music Supervision by Michael Dilbeck, Brooks Arthur, and Kevin Grady. Just Go With It has been rated PG-13 by the Motion Picture Association of America for Frequent Crude and Sexual Content, Partial Nudity, Brief Drug References and Language. The film will be released in theaters nationwide on February 11, 2011. 1 ABOUT THE FILM At the center of Just Go With It is an everyday guy who has let a careless lie get away from him. ―At the beginning of the movie, my character, Danny, was going to get married, but he gets his heart broken,‖ says Adam Sandler. -

PAJ77/No.03 Chin-C

AIN’T NO SUNSHINE The Cinema in 2003 Larry Qualls and Daryl Chin s 2003 came to a close, the usual plethora of critics’ awards found themselves usurped by the decision of the Motion Picture Producers Association of A America to disallow the distribution of screeners to its members, and to any organization which adheres to MPAA guidelines (which includes the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences). This became the rallying cry of the Independent Feature Project, as those producers who had created some of the most notable “independent” films of the year tried to find a way to guarantee visibility during award season. This issue soon swamped all discussions of year-end appraisals, as everyone, from critics to filmmakers to studio executives, seemed to weigh in with an opinion on the matter of screeners. Yet, despite this media tempest, the actual situation of film continues to be precarious. As an example, in the summer of 2003 the distribution of films proved even more restrictive, as theatres throughout the United States were block-booked with the endless cycle of sequels that came from the studios (Legally Blonde 2, Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle, Terminator 3, The Matrix Revolutions, X-2: X-Men United, etc.). A number of smaller films, such as the nature documentary Winged Migration and the New Zealand coming-of-age saga Whale Rider, managed to infiltrate the summer doldrums, but the continued conglomeration of distribution and exhibition has brought the motion picture industry to a stultifying crisis. And the issue of the screeners was the rallying cry for those working on the fringes of the industry, the “independent” producers and directors and small distributors. -

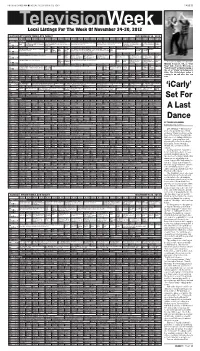

'Icarly' Set for a Last Dance

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 23, 2012 PAGE 5B TelevisionWeek Local Listings For The Week Of November 24-30, 2012 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT NOVEMBER 24, 2012 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Potential- 3 Steps to Incredible Health! With A Classic Gospel Special: Tent Revival Doo Wop Discoveries (My Music) R&B and pop Motown: Big Hits and More (My Music) Origi- Muddy Waters & the Rolling Live From the Artists Globe PBS Mark Joel Fuhrman, M.D. Joel Fuhrman’s Homecoming Spirit of tent revival meetings. (In vocal groups. (In Stereo) Å nal Motown classics. (In Stereo) Å Stones Live The Rolling Stones visit Den “Mayer Hawthorne” Trekker KUSD ^ 8 ^ health plan. Å Stereo) Å club. (In Stereo) Å Å KTIV $ 4 $ College Football Paid News News 4 Insider ›› “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull” News 4 Saturday Night Live Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House College Football Grambling State vs. Southern. Paid Pro- NBC KDLT The Big ›› “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull” (2008, Ad- KDLT Saturday Night Live (In Stereo) Å The Simp- According (Off Air) NBC (N) (In Stereo Live) Å gram Nightly News Bang venture) Harrison Ford, Cate Blanchett, Shia La Beouf. Indy and a deadly News sons Å to Jim Å KDLT % 5 % News (N) (N) Å Theory Soviet agent vie for a powerful artifact. -

BEDTIME STORIES Bobbi

THIS MATERIAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE ONLINE AT http://www.wdsfilmpr.com © Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved. disney.com/BedtimeStories WALT DISNEY PICTURES Unit Production Manager . GARRETT GRANT Presents First Assistant CREDITS Director . DANIEL SILVERBERG A Second Assistant Director . CONTE MATAL HAPPY MADISON Creatures Designed by. CRASH MCCREERY Production Production Supervisor . ROBERT WEST A CAST CONMAN & IZZY Skeeter Bronson. ADAM SANDLER Production Jill . KERI RUSSELL Kendall . GUY PEARCE An Mickey. RUSSELL BRAND OFFSPRING Barry Nottingham . RICHARD GRIFFITHS Production Violet Nottingham. TERESA PALMER Aspen. LUCY LAWLESS Wendy . COURTENEY COX Patrick . JONATHAN MORGAN HEIT BEDTIME STORIES Bobbi . LAURA ANN KESLING Marty Bronson . JONATHAN PRYCE Engineer . NICK SWARDSON A Film by Mrs. Dixon . KATHRYN JOOSTEN ADAM SHANKMAN Ferrari Guy. ALLEN COVERT Hot Girl . CARMEN ELECTRA Young Barry Nottingham . TIM HERLIHY Directed by . ADAM SHANKMAN Young Skeeter . THOMAS HOFFMAN Screenplay by . MATT LOPEZ Young Wendy . ABIGAIL LEONE DROEGER and TIM HERLIHY Young Mrs. Dixon. MELANY MITCHELL Story by. MATT LOPEZ Young Mr. Dixon . ANDREW COLLINS Produced by. ANDREW GUNN Donna Hynde. AISHA TYLER Produced by . ADAM SANDLER Hokey Pokey Women. JULIA LEA WOLOV JACK GIARRAPUTO DANA MIN GOODMAN Executive Producers . ADAM SHANKMAN SARAH G. BUXTON JENNIFER GIBGOT CATHERINE KWONG ANN MARIE SANDERLIN LINDSEY ALLEY GARRETT GRANT Bikers. BLAKE CLARK Director of BILL ROMANOWSKI Photography . MICHAEL BARRETT Hot Dog Vendor . PAUL DOOLEY Production Designer . LINDA DESCENNA Birthday Party Kids . JOHNTAE LIPSCOMB Edited by. TOM COSTAIN JAMES BURDETTE COWELL MICHAEL TRONICK, A.C.E. Angry Dwarf . MIKEY POST Costume Designer . RITA RYACK Gremlin Driver . SEBASTIAN SARACENO Visual Effects Cubby the Supervisor. JOHN ANDREW BERTON, JR. Home Depot Guy .