The Pre-Industrial Condition of the Forest Limits of Corner Brook Pulp and Paper Limited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Langelier Index Summary for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland

Water Resources Langelier Index Summary for Public Water Supplies in Management Division Newfoundland and Labrador Community Name Serviced Area Source Name Sample Date Langelier Index Bauline Bauline #1 Brook Path Well May 29, 2020 -1.06 Bay St. George South Highlands #3 Brian Pumphrey Well May 20, 2020 -0.29 Highlands Birchy Bay Birchy Bay Jumper's Pond May 06, 2020 -2.64 Bonavista Bonavista Long Pond May 01, 2020 -1.77 Brent's Cove Brent's Cove Paddy's Pond May 19, 2020 -5.85 Centreville-Wareham-Trinity Trinity Southwest Feeder Pond May 21, 2020 -3.64 Chance Cove Upper Cove Hollett's Well Jun 11, 2020 -2.17 Channel-Port aux Basques Channel-Port Aux Basques Gull Pond & Wilcox Pond May 20, 2020 -2.41 Clarenville Clarenville, Shoal Harbour Shoal Harbour River Jun 05, 2020 -2.23 Conception Bay South Conception Bay South Bay Bulls Big Pond May 28, 2020 -1.87 Corner Brook Corner Brook (+Massey Trout Pond, Third Pond (2 Jun 19, 2020 -1.88 Drive, +Mount Moriah) intakes) Fleur de Lys Fleur De Lys First Pond, Narrow Pond May 19, 2020 -3.41 Fogo Island Fogo Freeman's Pond Jun 09, 2020 -6.65 Fogo Island Fogo Freeman's Pond Jun 09, 2020 -6.54 Fogo Island Fogo Freeman's Pond Jun 09, 2020 -6.33 Gander Gander Gander Lake May 25, 2020 -2.93 Gander Bay South Gander Bay South - PWDU Barry's Brook May 20, 2020 -4.98 Gander Bay South George's Point, Harris Point Barry's Brook May 20, 2020 -3.25 Grand Falls-Windsor Grand Falls-Windsor Northern Arm Lake Jun 01, 2020 -2.80 (+Bishop's Falls, +Wooddale, +Botwood, +Peterview) Grates Cove Grates Cove Centre #1C -

A Community Needs and Resources Assessment for the Port Aux Basques and Burgeo Areas

PRIMARY HEALTH CARE IN ACTION A Community Needs and Resources Assessment for the Port aux Basques and Burgeo Areas 2013 Prepared by: Danielle Shea, RD, M.Ad.Ed. Primary Health Care Manager, Bay St. George Area Table of Contents Executive Summary Page 4 Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Page 6 Survey Overview Page 6 Survey Results Page 7 Demographics Page 7 Community Services Page 8 Health Related Community Services Page 10 Community Groups Page 15 Community Concerns Page 16 Other Page 20 Focus Group Overview Page 20 Port aux Basques: Cancer Care Page 21 Highlights Page 22 Burgeo: Healthy Eating Page 23 Highlights Page 24 Port aux Basques and Burgeo Areas Overview Page 26 Statistical Data Overview Page 28 Statistical Data Page 28 Community Resource Listing Overview Page 38 Port aux Basques Community Resource Listing Page 38 Burgeo Community Resource Listing Page 44 Strengths Page 50 Recommendations Page 51 Conclusion Page 52 References Page 54 Appendix A Page 55 Primary Health Care Model Appendix B Page 57 Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Policy Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Port aux Basques/ Burgeo Area Page 2 Appendix C Page 62 Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Survey Appendix D Page 70 Port aux Basques Focus Group Questions Appendix E Page 72 Burgeo Focus Group Questions Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Port aux Basques/ Burgeo Area Page 3 Executive Summary Primary health care is defined as an individual’s first contact with the health system and includes the full range of services from health promotion, diagnosis, and treatment to chronic disease management. -

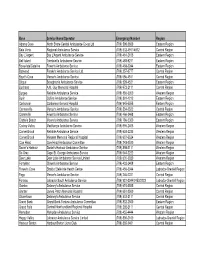

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

Central Newfoundland Solid Waste Management Plan

CENTRAL NEWFOUNDLAND SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN Phase I Report Volume I Final Report Submitted to Central Newfoundland Waste Management Committee BNG PROJECT # 721947 Fogo Crow Head Glovers Harbour New-Wes-Valley Wooddale Badger Gander Grand Falls-Windsor Salvage Buchans CENTRAL NEWFOUNDLAND SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN Phase I Report Final Report Submitted to: Central Newfoundland Waste Management Committee c/o Town of Gander P.O. Box 280 Gander, NF A1V 1W6 Submitted by: BAE-Newplan Group Limited 1133 Topsail Road, Mount Pearl Newfoundland, Canada A1N 5G2 October, 2002 CENTRAL NEWFOUNDLAND SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN Phase I Report Project No.: 721947 Title: CENTRAL NEWFOUNDLAND SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN Phase I Report - Final Client: Central Newfoundland Waste Management Committee C 02/10/02 Final Report GW WM WM B 02/09/18 Final Draft Report GW/ZY WM WM A 02/06/05 Issued for Review GW/PH/ZY WM WM Rev. Date Page No. Description Prepared By Reviewed Approved yyyy/mm/dd By By CENTRAL NEWFOUNDLAND SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN Page i Phase I Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................1 1.1 Background and Objectives.........................................................................................1 2.0 STUDY AREA BOUNDARY ...........................................................................................3 3.0 POPULATION PROJECTION.........................................................................................6 -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

No Subordinate Legislation received at time of printing THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 84 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2009 No. 43 EMBALMERS AND FUNERAL DIRECTORS ACT, 2008 NOTICE The following is a list of names and addresses of Funeral Homes 2009 to whom licences and permits have been issued under the Embalmers and Funeral Directors Act, cE-7.1, SNL2008 as amended. Name Street 1 City Province Postal Code Barrett's Funeral Home Mt. Pearl 328 Hamilton Avenue St. John's NL A1E 1J9 Barrett's Funeral Home St. John's 328 Hamilton Avenue St. John's NL A1E 1J9 Blundon's Funeral Home-Clarenville 8 Harbour Drive Clarenville NL A5A 4H6 Botwood Funeral Home 147 Commonwealth Drive Botwood NL A0H 1E0 Broughton's Funeral Home P. O. Box 14 Brigus NL A0A 1K0 Burin Funeral Home 2 Wilson Avenue Clarenville NL A5A 2B6 Carnell's Funeral Home Ltd. P. O. Box 8567 St. John's NL A1B 3P2 Caul's Funeral Home St. John's P. O. Box 2117 St. John's NL A1C 5R6 Caul's Funeral Home Torbay P. O. Box 2117 St. John's NL A1C 5R6 Central Funeral Home--B. Falls 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Central Funeral Home--GF/Windsor 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Central Funeral Home--Springdale 45 Union Street Gr. Falls--Windsor NL A2A 2C9 Conway's Funeral Home P. O. Box 309 Holyrood NL A0A 2R0 Coomb's Funeral Home P. O. Box 267 Placentia NL A0B 2Y0 Country Haven Funeral Home 167 Country Road Corner Brook NL A2H 4M5 Don Gibbons Ltd. -

NEWFOUNDLAND and LABRADOR COLLEGE of OPTOMETRISTS Box 23085, Churchill Park, St

NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR COLLEGE OF OPTOMETRISTS Box 23085, Churchill Park, St. John's, NL A1B 4J9 Following are the names of Optometrists registered with the Newfoundland and Labrador College of Optometrists as of 1 January 2014 who hold a therapeutic drug certificate and may prescribe a limited number of medications as outlined in the following regulation: http://www.assembly.nl.ca/Legislation/sr/Regulations/rc120090.htm#3_ DR. ALPHONSUS A. BALLARD, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. JONATHAN BENSE, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. GARRY C. BEST, GANDER, NL DR. JUSTIN BOULAY, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. LUC F. BOULAY, ST. JOHN'S, NL DR. RICHARD A. BUCHANAN, SPRINGDALE, NL DR. ALISON CAIGER-WATSON, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. JOHN M. CASHIN, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. GEORGE COLBOURNE, CORNER BROOK, NL DR. DOUGLAS COTE, PORT AUX BASQUES, NL DR. CECIL J. DUNCAN, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. CARL DURAND, CORNER BROOK, NL DR. RACHEL GARDINER, GOULDS, NL DR. CLARE HALLERAN, CLARENVILLE, NL DR. DEAN P. HALLERAN, CLARENVILLE, NL DR. DEBORA HALLERAN, CLARENVILLE, NL DR. KEVIN HALLERAN, MOUNT PEARL, NL DR. ELSIE K. HARRIS, STEPHENVILLE, NL DR. JESSICA HEAD, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL 1 of 3 DR. IAN HENDERSON, ST. JOHN'S, NL DR. PAUL HISCOCK, ST. JOHN'S, NL DR. LISA HOUNSELL, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. RICHARD J. HOWLETT, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. SARAH HUTCHENS, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. GRACE HWANG, GRAND FALLS-WINDSOR, NL DR. PATRICK KEAN, BAY ROBERTS, NL DR. NADINE KIELLEY, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. CHRISTIE LAW, ST. JOHN’S, NL DR. ANGELA MacDONALD, SYDNEY, NS DR. -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

Office Allowances - Office Accommodations 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19

House of Assembly Newfoundland and Labrador Member Accountability and Disclosure Report Office Allowances - Office Accommodations 01-Apr-18 to 31-Mar-19 Dean, Jerry, MHA Page: 1 of 1 Summary of Transactions Processed to Date for Fiscal 2018/19 Expenditure Limit (Net of HST): $19,200.00 Transactions Processed as of: 31-Mar-19 Expenditures Processed to Date (Net of HST): $19,200.00 Funds Available (Net of HST): $0.00 Percent of Funds Expended to Date: 100.0% Date Source Document # Vendor Name Expenditure Details Amount 01-Apr-18 HOA004815 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. 01-May-18 HOA004871 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. 01-Jun-18 HOA004908 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. 01-Jul-18 HOA004946 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. 01-Aug-18 HOA004983 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. 01-Sep-18 HOA005021 W REID CONSTRUCTION Lease payment for the Constituency Office of the MHA for the District of Exploits 1,600.00 LTD located in Bishop's Falls. -

Fire Protection and Detection Equipment Servicing Licence

Fire Protection and Detection Equipment Servicing Licence Portable Fire Extinguisher Licence FESNL-1 Company Address City Province Postal/Zip Code Licence Number Expiry Date Status Bell Aliant 332 O'Connell Drive Corner Brook NL A2H 7E5 FESNL-100000-004 June 17, 2018 Issued BMB Fire Management & Consulting 38 Gillis Drive Stephenville NL A2N 3R6 FESNL-100000-047 September 13, 2018 Issued BMS Extinguishers Ltd. P.O. Box 196 Salmon Cove NL A0A 3S0 FESNL-100000-019 June 19, 2018 Issued BP Fire & Safety P.O. Box 1957 Marystown NL A0E 2M0 FESNL-100000-045 August 29, 2018 Issued DASIT Recharging P.O. Box 649 Grand Falls-Windsor NL A2A 2K2 FESNL-125000-008 June 18, 2018 Issued DN's Canopy Cleaning 18 Byrne's Road Paradise NL A1L 3S7 FESNL-120000-015 June 19, 2018 Issued Fire-Tech Systems Ltd. P.O. Box 28105 St. John's NL A1B 4J8 FESNL-146000-032 July 17, 2018 Issued Gicleurs De La Mauricie Inc. 310 Place Nolin Trois-Rivieres QC G8T 8B5 FESNL-156000-053 March 20, 2020 Issued Gros Morne Safety Services P.O. Box 329, 121 Main Street Rocky Harbour NL A0K 4N0 FESNL-100000-006 June 17, 2018 Issued Happy Valley-Goose Bay Town Council P.O. Box 40, Station B Happy Valley-Goose Bay NL A0P 1E0 FESNL-100000-040 July 31, 2018 Issued Healey's Code Red Fire & Safety Ltd. 37 Freshwater Crescent Freshwater, PB NL A0B 1W0 FESNL-120000-009 June 18, 2018 Issued Holwell's Fire & Safety 33 Acharya Drive Paradise NL A1L 2S9 FESNL-100000-034 July 22, 2018 Issued K & D Pratt Group Inc. -

Hearing Aid Providers (Including Audiologists)

Hearing Aid Providers (including Audiologists) Beltone Audiology and Hearing Clinic Inc. 16 Pinsent Drive Grand Falls-Windsor, NL A2A 2R6 1-709-489-8500 (Grand Falls-Windsor) 1-866-489-8500 (Toll free) 1-709-489-8497 (Fax) [email protected] Audiologist: Jody Strickland Hearing Aid Practitioners: Joanne Hunter, Jodine Reid Satellite Locations: Baie Verte, Burgeo, Cow Head, Flower’s Cove, Harbour Breton, Port Saunders, Springdale, Stephenville, St. Albans, St. Anthony ________________________________ Beltone Audiology and Hearing Clinic Inc. 3 Herald Avenue Corner Brook, NL A2H 4B8 1-709-639-8501 (Corner Brook) 1-866-489-8500 (Toll free) 1-709-639-8502 (Fax) [email protected] Audiologist: Jody Strickland Hearing Aid Practitioner: Jason Gedge Satellite Locations: Baie Verte, Burgeo, Cow Head, Flower’s Cove, Harbour Breton, Port Saunders, Springdale, Stephenville, St. Albans, St. Anthony ________________________________ Beltone Hearing Service 3 Paton Street St. John’s, NL A1B 4S8 1-709-726-8083 (St. John’s) 1-800-563-8083 (Toll free) 1-709-726-8111 (Fax) [email protected] www.beltone.nl.ca Audiologists: Brittany Green Hearing Aid Practitioners: Mike Edwards, David King, Kim King, Joe Lynch, Lori Mercer Satellite Locations: Bay Roberts, Bonavista, Carbonear, Clarenville, Gander, Grand Bank, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador City, Lewisporte, Marystown, New-Wes- Valley, Twillingate ________________________________ Exploits Hearing Aid Centre 9 Pinsent Drive Grand Falls-Windsor, NL A2A 2S8 1-709-489-8900 (Grand Falls-Windsor) 1-800-563-8901 (Toll free) 1-709-489-9006 (Fax) [email protected] www.exploitshearing.ca Hearing Aid Practitioners: Dianne Earle, William Earle, Toby Penney ________________________________ Maico Hearing Service 84 Thorburn Road St. -

Student and Youth Services Agreement.Xlsx

2015-16 Student and Youth Services Agreement Approvals Organization Location Project Approved Amount BOTWOOD BOYS AND GIRLS CLUB Botwood Youth Cordinator$ 40,100 CBDC TRINITY CONCEPTION CORPORATION Carbonear Community Youth Coordinator$ 87,500 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Small Enterprise Co-Operative Placement Assistance$ 229,714 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Student Works and Service Program (SWASP)$ 90,155 COLLEGE OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC St. John's Partnership in Academic Career Education Employment Program $ 57,232 (PACEE) COMMUNITY YOUTH NETWORK CORNER BROOK & AREA Corner Brook Impact $ 5,071 CONSERVATION CORPS NEWFOUNDLAND AND St. John's Green Team$ 579,600 LABRADOR FOR THE LOVE OF LEARNING, INC St. John's Watering the Seeds$ 115,000 HARBOUR BRETON COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Breton Youth Entreprensurial Skills$ 35,000 HARBOUR BRETON COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Breton Youth Outreach Coordinator$ 52,500 HARBOUR GRACE COMMUNITY YOUTH Harbour Grace Changing Lanes$ 60,301 KANGIDLUASUK STUDENT PROGRAM INC Nain Student Program$ 7,000 MARINE INSTITUTE St. John's Youth Opportinities Coop Program$ 100,000 MARINE INSTITUTE St. John's Wage Subsidies for MESD$ 11,186 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Small Enterprise Co-Operative Placement Assistance$ 522,993 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Graduate Transition to Employment (GTEP)$ 200,000 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Student Works and Service Program (SWASP)$ 331,680 MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NL St. John's Partnership in Academic Career Education Employment Program $ 67,732 (PACEE) NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR ASSOC OF Mount Pearl Youth Ventures$ 82,000 COMMUNITY BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT CORPORATIONS SKILLS CANADA-NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR St. -

BOARD MEETING –Norris Arm 1:00 P.M. December 7, 2017 Attendance

Central Newfoundland Waste Management P. O. Box 254, Norris Arm, NL, A0G 3M0 Phone: 709 653 2900 Fax :709 653 2920 Web: www.cnwmc.com E-mail: [email protected] BOARD MEETING –Norris Arm 1:00 p.m. December 7, 2017 Attendance Terry Best Badger/Buchans/Buchans Junction/Millertown – Ward 1 Kevin Butt NWI/Twillingate – Ward 3 Wayne Collins Fogo Island – Ward 4 Keith Howell Gander Bay – Ward 5 Lloyd Pickett Indian Bay – Ward 6 Glenn Arnold Terra Nova – Ward 7 Percy Farwell Town of Gander - Ward 8 Darrin Finn Town of Grand Falls-Windsor – Ward 9 Ross Rowsell Norris Arm/Norris Arm North – Ward 11 Derrick Luff Direct Haul – Ward 12 Ed Evans Chief Administrative Officer - CNWM Karen White Attwood Manager of Finance/Administration – CNWM Mark Attwood Manager of Operations – CNWM Jerry Collins Dept of Municipal Affairs and Environment - Conference Call Ian Duffett Dept of Municipal Affairs and Environment – Conference Call Apologies Brad Hefford Service NL Wayne Lynch Service NL Robert Elliott Point Leamington – Ward 2 Perry Pond Bishops Falls/Botwood/Lewisporte – Ward 10 1. Review of Minutes of November 9, 2017 MOTION: Moved by G. Arnold to adopt the minutes of November 9, 2017. Seconded by R. Rowsell. M/C 2. Business Arising Mayor Betty Clarke has stepped down as representative of Ward 10 (Botwood, Bishops Falls, and Lewisporte). Perry Pond will now represent Ward 10. 3. Technical Committee – Representatives from the Board, Government and engineers from the Towns of Grand Falls – Windsor and Gander will continue to sit at the Technical committee December 7, 2017 4. Financial Report MOTION: Moved by W.