The Tarahumara Frog: Return of a Native

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tectonic Evolution of the Madrean Archipelago and Its Impact on the Geoecology of the Sky Islands

The Tectonic Evolution of the Madrean Archipelago and Its Impact on the Geoecology of the Sky Islands David Coblentz Earth and Environmental Sciences Division, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM Abstract—While the unique geographic location of the Sky Islands is well recognized as a primary factor for the elevated biodiversity of the region, its unique tectonic history is often overlooked. The mixing of tectonic environments is an important supplement to the mixing of flora and faunal regimes in contributing to the biodiversity of the Madrean Archipelago. The Sky Islands region is located near the actively deforming plate margin of the Western United States that has seen active and diverse tectonics spanning more than 300 million years, many aspects of which are preserved in the present-day geology. This tectonic history has played a fundamental role in the development and nature of the topography, bedrock geology, and soil distribution through the region that in turn are important factors for understanding the biodiversity. Consideration of the geologic and tectonic history of the Sky Islands also provides important insights into the “deep time” factors contributing to present-day biodiversity that fall outside the normal realm of human perception. in the North American Cordillera between the Sierra Madre Introduction Occidental and the Colorado Plateau – Southern Rocky The “Sky Island” region of the Madrean Archipelago (lo- Mountains (figure 1). This part of the Cordillera has been cre- cated between the northern Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico ated by the interactions between the Pacific, North American, and the Colorado Plateau/Rocky Mountains in the Southwest- Farallon (now entirely subducted under North America) and ern United States) is an area of exceptional biodiversity and has Juan de Fuca plates and is rich in geology features, including become an important study area for geoecology, biology, and major plateaus (The Colorado Plateau), large elevated areas conservation management. -

Stories of the Sky Islands: Exhibit Development Resource Guide for Biology and Geology at Chiricahua National Monument and Coronado National Memorial

Stories of the Sky Islands: Exhibit Development Resource Guide for Biology and Geology at Chiricahua National Monument and Coronado National Memorial Prepared for the National Park Service under terms of Cooperative Ecosystems Studies Unit Agreement H1200-05-0003 Task Agreement J8680090020 Prepared by Adam M. Hudson,1 J. Jesse Minor,2,3 Erin E. Posthumus4 In cooperation with the Arizona State Museum The University of Arizona Tucson, AZ Beth Grindell, Principal Investigator May 17, 2013 1: Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona ([email protected]) 2: School of Geography and Development, University of Arizona ([email protected]) 3: Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, University of Arizona 4: School of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of Arizona ([email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................3 Beth Grindell, Ph.D. Ch. 1: Current research and information for exhibit development on the geology of Chiricahua National Monument and Coronado National Memorial, Southeast Arizona, USA..................................................................................................................................... 5 Adam M. Hudson, M.S. Section 1: Geologic Time and the Geologic Time Scale ..................................................5 Section 2: Plate Tectonic Evolution and Geologic History of Southeast Arizona .........11 Section 3: Park-specific Geologic History – Chiricahua -

United States Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Office 9828 N

United States Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Office 9828 N. 31st Avenue Ste C3 Phoenix, AZ 85051 Telephone: (602) 242-0210 Fax: (602) 242-2513 AESO/SE 22410-2011-F-0210 September 27, 2016 Ms. Laura Jo West, Forest Supervisor Coconino National Forest 1824 South Thompson Street Flagstaff, Arizona 8600 I RE: Rock Pits Project, Coconino and Kaibab National Forests Dear Ms. West: Thank you for your request for formal consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) pursuant to section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (16 U.S.C. 1531-1544), as amended (Act). Your request and biological assessment (BA) were dated March 29, 2016, and received by us on April 4, 2016. This consultation concerns the potential effects of activities associated with the development and operation of rock pits on the Coconino and Kaibab National Forests in Coconino and Yavapai Counties, Arizona. The Forest Service has determined that the proposed action may affect, and is likely to adversely affect, the threatened Mexican spotted owl (Strix occidenta/is lucida) and its critical habitat. You have also requested our concurrence that the proposed action may affect, but is not likely to adversely affect the endangered California condor (Gymnogyps ca/ifornianus) outside of the lOj experimental nonessential population area, and "is not likely to jeopardize" the condor within the 1Oj experimental nonessential population area. We concur with your determinations. The basis for our concurrences is found in Appendix A. You also requested that we provide our technical assistance with respect to compliance with the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act (16 U.S.C. -

You Can Learn More About the Chiricahuas

Douglas RANGER DISTRICT www.skyislandaction.org 2-1 State of the Coronado Forest DRAFT 11.05.08 DRAFT 11.05.08 State of the Coronado Forest 2-2 www.skyislandaction.org CHAPTER 2 Chiricahua Ecosystem Management Area The Chiricahua Mountain Range, located in the Natural History southeastern corner of the Coronado National Forest, The Chiricahua Mountains are known for their is one of the largest Sky Islands in the U.S. portion of amazing variety of terrestrial plants, animals, and the Sky Island region. The range is approximately 40 invertebrates. They contain exceptional examples of miles long by 20 miles wide with elevations ranging ecosystems that are rare in southern Arizona. While from 4,400 to 9,759 feet at the summit of Chiricahua the range covers only 0.5% of the total land area in Peak. The Chiricahua Ecosystem Management Area Arizona, it contains 30% of plant species found in (EMA) is the largest Management Area on the Forest Arizona, and almost 50% of all bird species that encompassing 291,492 acres of the Chiricahua and regularly occur in the United States.1 The Chiricahuas Pedragosa Mountains. form part of a chain of mountains spanning from Protected by remoteness, the Chiricahuas remain central Mexico into southern Arizona. Because of one of the less visited ranges on the Coronado their proximity to the Sierra Madre, they support a National Forest. Formerly surrounded only by great diversity of wildlife found nowhere else in the ranches, the effects of Arizona’s explosive 21st century United States such as the Mexican Chickadee, whose population growth are beginning to reach the flanks only known breeding locations in the country are in of the Chiricahuas. -

Management Indicator Species of the Kaibab National Forest: an Evaluation of Population and Habitat Trends Version 3.0 2010

Management Indicator Species of the Kaibab National Forest: an evaluation of population and habitat trends Version 3.0 2010 Isolated aspen stand. Photo by Heather McRae. Pygmy nuthatch. Photo by the Smithsonian Inst. Pumpkin Fire, Kaibab National Forest Mule deer. Photo by Bill Noble Red-naped sapsucker. Photo by the Smithsonian Inst. Northern Goshawk © Tom Munson Tree encroachment, Kaibab National Forest Prepared by: Valerie Stein Foster¹, Bill Noble², Kristin Bratland¹, and Roger Joos³ ¹Wildlife Biologist, Kaibab National Forest Supervisor’s Office ²Forest Biologist, Kaibab National Forest, Supervisor’s Office ³Wildlife Biologist, Kaibab National Forest, Williams Ranger District Table of Contents 1. MANAGEMENT INDICATOR SPECIES ................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 Regulatory Background ...................................................................................................... 8 Management Indicator Species Population Estimates ...................................................... 10 SPECIES ACCOUNTS ................................................................................................ 18 Aquatic Macroinvertebrates ...................................................................................... 18 Cinnamon Teal .......................................................................................................... 21 Northern Goshawk ................................................................................................... -

A BRIEF HISTORY of DISCOVERY in the GULF of CALIFORNIA © Richard C

A BRIEF HISTORY OF DISCOVERY IN THE GULF OF CALIFORNIA © Richard C. Brusca Vers. 12 June 2021 (All photos by the author, unless otherwise indicated) value of their visits. And there is good FIRST DISCOVERIES evidence that the Seri People (Comcaac) of San Esteban Island, and native people of Archaeological evidence tells us that Native the Baja California peninsula, ate sea lions. Americans were present in northwest Mexico at least 13,000 years ago. Although these hunter-gatherers probably began visiting the shores of the Northern Gulf of California around that time, any early evidence has been lost as sea level has risen with the end of the last ice age. Sea level stabilized ~6000 years ago (ybp), and the earliest evidence of humans along the shores of Sonora and Baja California (otoliths, or fish ear bones from shell middens) is around that age. Excavations of shell middens from the Bahía Adair and Puerto Peñasco region of the Upper Gulf show more-or-less continuous use of the coastal area over the past 6000 years (Middle Archaic Period; based on Salina Grande, on the upper Sonoran coast; radiocarbon dates of charcoal and fish a huge salt flat in which are found artesian otoliths to ~4270 BC). The subsistence springs (pozos) pattern of these midden sites suggests a The famous Covacha Babisuri lifestyle basically identical to that of the archaeological site on Isla Espíritu Santo, in earliest Sand Papago (Areneños, or Hia ced the Southern Gulf, has yielded evidence of O’odham) (see Mitchell et al. 2020). indigenous use that included harvesting and In the coastal shallows, Native working pearls as much as 8,500 years ago. -

Warshall (1994)

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. l Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. f:~~ United States ~.~flWJ" .,.} Department of Biodiversity and \'''',,;,..• .-.1' (I Ag ricultu re Forest Service Management of the Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Madrean Archipelago: Experiment Station The Sky Islands of Fort Collins, CO 80526 Southwestern United States and General Technical Northwestern Mexico Report RM-GTR-264 September 19-23, 1994 Tucson, Arizona USDA Forest Service July 1995 General Technical Report RM-GTR-264 Biodiversity and Management of the Madrean Archipelago: The Sky Islands of Southwestern United States and Northwestern Mexico September 19-23, 1994 Tucson, Arizona Technical Coordinators: Leonard F. DeSano Peter F. Ffolliott Gerald J. Gottfried University of Arizona Robert H. Hamre Carleton S. Edminster Alfredo Ortega-Rubio Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Centro de Investigaciones Biologicas Experiment Station del Noroeste Page Design: Carol LoSapio Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station Sponsors: Rocky Mountain Forest and Range School of Renewable Natural Resources Experiment Station University of Arizona U.S. Department of Agriculture Tucson, Arizona Fort Collins, Colorado The Madrean Sky Island Archipelago: A Planetary Overview Peter Warshall 1 Abstract.-Previous work on biogeographic isolation has concerned itself with oceanic island chains, islands associated with continents, fringing archipelagos, and bodies of water such as the African lake system which serve as "aquatic islands". This paper reviews the "continental islands" and compares them to the Madrean sky island archipelago. The geological, hydrological, and climatic context for the Afroalpine, Guyana, Paramo, low and high desert of the Great Basin, etc. -

Merging Science and Management in a Rapidly Changing World

Biodiversity in the Madrean Archipelago of Sonora, Mexico Thomas R. Van Devender, Sergio Avila-Villegas, and Melanie Emerson Sky Island Alliance, Tucson, Arizona Dale Turner The Nature Conservancy, Tucson, Arizona Aaron D. Flesch University of Montana, Missoula, Montana Nicholas S. Deyo Sky Island Alliance, Tucson, Arizona Introduction open to incursions of frigid Arctic air from the north, and the Sierra Madres Oriental and Occidental create a double rain shadow and Flowery rhetoric often gives birth to new terms that convey images the Chihuahuan Desert. Madrean is a general term used to describe and concepts, lead to inspiration and initiative. On the 1892-1894 things related to the Sierra Madres. In a biogeographical analysis of expedition to resurvey the United States-Mexico boundary, Lieutenant the herpetofauna of Saguaro National Monument, University of Arizona David Dubose Gaillard described the Arizona-Sonora borderlands as herpetologist and ecologist Charles H. Lowe was probably the first to “bare, jagged mountains rising out of the plains like islands from the use the term ‘Madrean Archipelago’ to describe the Sky Island ranges sea” (Mearns 1907; Hunt and Anderson 2002). Later Galliard was between the Sierra Madre Occidental in Sonora and Chihuahua and the the lead engineer on the Panama Canal construction project. Mogollon Rim of central Arizona (Lowe, 1992). Warshall (1995) and In 1951, Weldon Heald, a resident of the Chiricahua Mountains, McLaughlin (1995) expanded and defined the area and concept. coined the term ‘Sky Islands’ for the ranges in southeastern Arizona (Heald 1951). Frederick H. Gehlbach’s 1981 book, Mountain Islands and Desert Seas: A Natural History of the US-Mexican Borderlands, Biodiversity provided an overview of the natural history of the Sky Islands in In 2007, Conservation International named the Madrean Pine-oak the southwestern United States. -

A Study of Taxonomy and Phylogeny of Lampropeltis Pyromelana Cope

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 13 Number 1 – Number 2 Article 9 9-12-1953 A study of taxonomy and phylogeny of Lampropeltis pyromelana Cope Wilmer W. Tanner Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Tanner, Wilmer W. (1953) "A study of taxonomy and phylogeny of Lampropeltis pyromelana Cope," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 13 : No. 1 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol13/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A STUDY OF TAXONOMY AND PHYLOGENY OF LAMPROPELTIS PYROMELANA COPE (I) WILMER W. TANNER Brigham Young University Since the publication of Blanchard's "A Revislon of the King Snakes Genus Lampropeltis," (1921) the species L. pyromelana has received little attention from herpetological workers. During the course of these years, many additional specimens have been collected from the then-known range of Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Chihuahua. Northeastern Sonora and east central Nevada have since been added to the range. These additions, particularly those specimens from the northern parts of the range, have revealed geo- graphic variat~onsnot previously detected, and have indicated a need for a re-examination of the intraspecif~cand interspecific relation- ships of this species. HISTORICAL REVIEW The original description of Ophibolus pyromenlanus Cope (1866) was based primarily on a few specimens from Fort Whipple, Arizona. -

Comparison of the Tropical Floras of the Sierra La Madera and the Sierra Madre Occidental, Sonora, Mexico

Comparison of the Tropical Floras of the Sierra la Madera and the Sierra Madre Occidental, Sonora, Mexico Thomas R. Van Devender Sky Island Alliance, Tucson, Arizona Gertrudis Yanes-Arvayo Universidad de la Sierra, Moctezuma, Sonora, Mexico Ana Lilia Reina-Guerrero Sky Island Alliance, Tucson, Arizona Melissa Valenzuela-Yánez, Maria de la Paz Montañez-Armenta, and Hugo Silva-Kurumiya Universidad de la Sierra, Moctezuma, Sonora, Mexico Abstract—The floras of the tropical vegetation in the Sky Island Sierra la Madera (SMA) near Moctezuma in northeastern Sonora (30°00’N 109°18’W) and the Yécora (YEC) area in the Sierra Madre Occidental (SMO) in eastern Sonora (28°25’N 109°15”W) were compared. The areas are 175 km apart. Tropical vegetation includes foothills thornscrub (FTS) in both areas and tropical deciduous forest (TDF) in the Yécora area. A total of 893 vascular plant taxa are known from these areas with 433 taxa in FTS and 793 in TDF. FTS in SMA and YEC (near Curea) had 220 and 298 taxa, with most of them also in TDF (69.5% and 82.9%). Only 83 taxa in TDF were shared between SMA and YEC (37.7% and 27.9% of the floras). The 49 FTS species in SMA but not YEC were not in TDF either, reflecting biotic influences from the Sonoran Desert (10), southwestern United States (8), Madrean Archipelago (6), and a few from oak woodland and tropical western Mexico. One species (Pseudabutilon thurberi) is endemic to central Sonora and adjacent Arizona. Affinities to the New World tropics are very strong in both areas. -

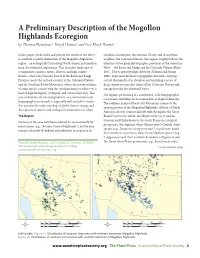

A Preliminary Description of the Mogollon Highlands Ecoregion by Thomas Fleischner1, David Hanna1, and Lisa Floyd-Hanna2

A Preliminary Description of the Mogollon Highlands Ecoregion by Thomas Fleischner1, David Hanna1, and Lisa Floyd-Hanna2 In this paper, we describe and present the results of our efort southern counterpart, the Sonoran Desert, and its northern to establish a spatial delineation of the Mogollon Highlands neighbor, the Colorado Plateau. Tis region roughly follows the region—an ecologically fascinating North American transition interface of two great physiographic provinces of the American zone of continental importance. Tis dramatic landscape of West — the Basin and Range and the Colorado Plateau (Hunt escarpments, canyons, mesas, deserts, and high conifer 1967). Due to great geologic diversity (Nations and Stump forests—where the Sonoran Desert of the Basin and Range 1996), it presents dramatic topographic diversity—varying Province meets the redrock country of the Colorado Plateau several thousand feet in elevation and including a series of and the Southern Rocky Mountains, where the northern limits deep canyon systems that drain of the Colorado Plateau and of some species coexist with the southern limits of others—is a emerge into the low Sonoran Desert. land of high biological, ecological, and cultural diversity. Tis Te region’s positioning at a continental-scale biogeographic area of dramatic elevational gradients, at a continental-scale crossroads contributes to its tremendous ecological diversity. biogeographic crossroads, is especially well-suited for studies Te southern extent of the Rocky Mountains intersects the that can provide understanding of global climate change and eastern portion of the Mogollon Highlands. All four of North the capacity of species and ecological communities to adapt. America’s deserts connect directly with the region: the Great The Region Basin Desert to the north, the Mojave to the west, and the Sonoran and Chihuahuan to the south. -

Geologic Transect Across the Northern Sierra Madre Occidental Volcanic fi Eld, Chihuahua and Sonora, Mexico

The Geological Society of America Digital Map and Chart Series 6 2007 Geologic transect across the northern Sierra Madre Occidental volcanic fi eld, Chihuahua and Sonora, Mexico Fred W. McDowell Department of Geological Sciences, Jackson School of Geosciences, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, USA ABSTRACT Eleven individual mapping projects by graduate students at The University of Texas at Austin have been compiled into a regional geologic map that comprises a 285-km-long east-west transect of the middle Tertiary Sierra Madre Occidental vol- canic fi eld at 28° to 28°30′ north latitude. The map area extends across the entire Sierra Madre Occidental plateau and eastward, to include faulted remnants of the volcanic fi eld in central Chihuahua. In order to portray the timing and evolution of the middle Tertiary volcanism at regional scale, the original volcanic map units have been condensed into a set of nine major units by grouping conformable sequences that have similar K-Ar ages. More recently obtained 40Ar-39Ar ages were used to refi ne the groupings. Original mapped and inferred faults, and known and interpreted cal- dera margins are also shown. During the mapping, suites of samples were collected for geochemistry and geo- chronology. A total of 223 such sample locations are plotted on the transect map. A link is provided between these locations and a master table that lists the type of data available for each sample. The original K-Ar geochronology and geochemistry (major- elements by wet chemistry and limited trace-element measurements) have been aug- mented subsequently by expanded trace-element concentration data, U-Pb, 40Ar-39Ar dating, and measurements of radiogenic and stable isotope ratios conducted on some of the original samples.