Assisted Suicide Advocate Jack Kevorkian Dies At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Necessary Right of Choice for Physician-Assisted Suicide

Student Publications Student Scholarship Fall 2017 The ecesN sary Right of Choice for Physician- Assisted Suicide Kerry E. Ullman Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Applied Ethics Commons, and the Ethics in Religion Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Ullman, Kerry E., "The eN cessary Right of Choice for Physician-Assisted Suicide" (2017). Student Publications. 574. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/574 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The ecesN sary Right of Choice for Physician-Assisted Suicide Abstract Research-based paper on the importance of the right for terminally ill patients facing a painful death to be able to choose how they end their life Keywords Assisted-Suicide, Maynard, Kevorkian, Terminally-ill Disciplines Applied Ethics | Ethics in Religion Comments Written for FYS 150: Death and the Meaning of Life. Creative Commons License Creative ThiCommons works is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This student research paper is available at The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ student_scholarship/574 Ullman 1 Kerry Ullman Professor Myers, Ph.D. Death and the Meaning of Life - FYS 30 November 2017 Assisted Suicide The Necessary Right of Choice for Physician-Assisted Suicide Imagine being told you have less than six months left to live. On top of that horrific news, you experience excruciating pain every single day that is far more atrocious than anything you could have possibly imagined. -

FENA Conversation with Fran

FINAL EXIT NETWORK VOL 18 • NO 1 WINTER, JAN/FEB 2019 CONTENTS TTHEHE TIME TO IMPROVE OREGON-STYLE LAWS? .........3 GOODGOOD DEMENTIA ADVANCE DEATHDEATH DIRECTIVES ...........................5 FISCAL YEAR REPORT ............9 SOCIETYSOCIETY AMERICANS ACCEPT FEN EUTHANASIA ..................... 11 A Conversation With Fran By Michael James, FEN Life Member enior Guide Fran Schindler’s voice was raspy after five days of protesting in Washington, DC, but this remarkable 79- Q: year-old’sS enthusiasm for FEN and life in general was loud and clear. “The privilege of someone being What’s going to willing to have me with them when they die, when I happen to you? only just sit with them, is the most meaningful thing I have ever done.” In the late 1980s, Fran faced a series of daunt- ing issues: a brain tumor, divorce, and mysterious A. symptoms which mimicked ALS. She acknowledg- es she became obsessed with finding ways to kill I will get dead. herself during those dark days. Eventually she heard Faye Girsh lecture about FEN. She quickly signed up for training and got her FEN membership card in November 2006. Twelve years later she estimates FRAN continued on page 2 Renew your membership online: www.finalexitnetwork.org FRAN continued from page 1 she’s been present for over 70 individuals who have taken their lives using FEN protocol. “At the FEN training class I discovered a major benefit of being a “Start doing FEN member. I looked at the trainers and my fellow classmates—people who didn’t know me—and real- what you want ized that if I needed them they would be there for me. -

Assisted Suicide, the Due Process Clause and "Fidelity in Translation"

Fordham Law Review Volume 63 Issue 4 Article 11 1995 Assisted Suicide, the Due Process Clause and "Fidelity in Translation" Willard C. Shih Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Willard C. Shih, Assisted Suicide, the Due Process Clause and "Fidelity in Translation", 63 Fordham L. Rev. 1245 (1995). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol63/iss4/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASSISTED SUICIDE, THE DUE PROCESS CLAUSE AND "FIDELITY IN TRANSLATION" WILLARD C. SHIH INTRODUCTION [T]he prospect of impossibility should not dissuade any scientist or doctor who is sincerely dedicated to the pursuit of empirical truth. A prerequisite for that noble aim is the ideal of unfettered experi- mentation on human death under impeccably ethical conditions. [Physician-assisted suicide], as I have outlined it, comes closest to that ideal, now and for the foreseeable future. The practice should be legitimized and implemented as soon as possible; but that calls for the strident advocacy of influential personalities who, unfortu- nately, choose to remain silent or disinterested-or simply antithetical.' Dr. Kevorkian authored this passage hoping that other physicians would read it and join his crusade supporting physician-assisted sui- cide. The mere mention of his name stirs up different images in peo- ple's minds. -

Physician-Assisted Death, Dementia, and Euthanasia: Using an Advanced Directive to Facilitate the Desires of Those with Impending Memory Loss Katie Franklin

Idaho Law Review Volume 51 | Number 2 Article 6 March 2019 Physician-Assisted Death, Dementia, and Euthanasia: Using an Advanced Directive to Facilitate the Desires of Those with Impending Memory Loss Katie Franklin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review Recommended Citation Katie Franklin, Physician-Assisted Death, Dementia, and Euthanasia: Using an Advanced Directive to Facilitate the Desires of Those with Impending Memory Loss, 51 Idaho L. Rev. 547 (2019). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho-law-review/vol51/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Idaho Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PHYSICIAN-ASSISTED DEATH, DEMENTIA, AND EUTHANASIA: USING AN ADVANCED DIRECTIVE TO FACILITATE THE DESIRES OF THOSE WITH IMPENDING MEMORY LOSS TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 547 II. THE STRUGGLE OF DEMENTIA ............................................................ 549 A. The Palliative Care Option ................................................................. 550 B. Physician-Assisted Death ................................................................... 551 i. Legalization ................................................................................... 552 III. HISTORY OF PHYSICIAN-ASSISTED -

If Kevorkian Could Meet Hippocrates Scott Av N Dyke Cedarville University

CedarEthics: A Journal of Critical Thinking in Bioethics Volume 7 Article 1 Number 2 2008 May 2008 If Kevorkian Could Meet Hippocrates Scott aV n Dyke Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The uthora s are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Van Dyke, Scott (2008) "If Kevorkian Could Meet Hippocrates," CedarEthics: A Journal of Critical Thinking in Bioethics: Vol. 7 : No. 2 , Article 1. DOI: 10.15385/jce.2008.7.2.1 Available at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedarethics/vol7/iss2/1 If Kevorkian Could Meet Hippocrates Browse the contents of this issue of CedarEthics: A Journal of Critical Thinking in Bioethics. Keywords Ethics, Kevorkian, Hippocrates Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedarethics Part of the Bioethics and Medical Ethics Commons This article is available in CedarEthics: A Journal of Critical Thinking in Bioethics: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedarethics/ vol7/iss2/1 CedarEthics 2008 Volume 7 Number 2 1 ⦁ ⦁ ⦁ If Kevorkian Could Meet Hippocrates Scott Van Dyke Cedarville University ack is sitting in his prison cell during the seventh year of his sentence for second degree murder. -

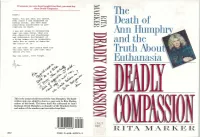

The Death of and the -1 Truth About, Euthanasia

If someone you care about bought FinaZElxit, you must buy them D~lyComl,assiOn. Derek : The There. You got what you wanted. Ever since I was diagnosed as having cancer, you have done Death of everything conceivable to pre- cipitate my death. I was not alone in recognizing what you were doing. What you Hulll~hrvA did--desertion and abandonment Ann and subsequent harrassment of a dying woman--is so unspeakble there are no words to describe -1 the horror of it. and the Yet you know. And others know too. You will have to live with this untiol you die. Truth About, 1 May you never, ever forget. Euthanasia This is the actual suicide letter left by Ann Humphry. The hand- written note was added by Ann to a copy sent to Rita Marker, author of this book. The letter itself was addressed to Ann's husband, Derek Humphry, co-founder of the Hemlock Society and author of the number-one best-seller Rnal Exit. - '1 MAR 1 t RITA MARKER ISBN 0-688-12223-3 8 ,'\- IF " ISBN 0-688-12221-3 FPT $18.00 wtinuedfiomfiotatjap) ,, Tack Kevorkian. who has written article advocating medical experiments on death row prisoners -while they are still alive. An( she explains the ramifications of euthanasia course is not the same as giving in a country without adequate health insur- doctors the right to kill ance, like America, where people who really their patients on demand. want to live might choose death rather than bankrupt their families. Deadly Compassion is essential reading for anyone who has misgivings about giving DEADLY COMPASSION doctors the right to kill. -

Physician-Assisted Suicide: Why Physicians Should Oppose It

Physician-Assisted Suicide: Why Physicians Should Oppose It Joseph E. Marine, MD, MBA Division of Cardiology Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine February 2, 2018 Disclosures • No relevant financial disclosures • I am a member of the American College of Physicians, the American Medical Association, and the Baltimore City Medical Society • All of these organizations oppose legalization of physician-assisted suicide and all other forms of euthanasia • There are no drugs or devices that have been approved by the US FDA for physician-assisted suicide or euthanasia Some Definitions • Physician-Assisted Suicide: A form of euthanasia (“good death) where a physician provides the means (such as a lethal drug prescription) for a patient to end his/her own life • Synonyms/ Euphemisms: • Physician/doctor-assisted death • Death with Dignity • End-of-Life Option • (Medical) Aid-in-Dying • includes euthanasia by lethal injection in Canada • Usual drugs used: 90-100 x 100 mg secobarbital tabs dissolved in liquid and swallowed quickly • Antiemetic premed usually given to prevent vomiting PAS/Euthanasia: Background • Mid-1800s – increasing medical use of morphine and chloroform anesthesia leads to proposals to use to hasten death for patients with advanced illnesses • 1906: Euthanasia law proposed in Ohio state legislature, voted down 79-23 • 1920s-1930s: Public support for euthanasia increases in USA, though not legally adopted • 1939-1945: WWII, Nuremberg trials Euthanasia in post-war era • 1945-1980: Little activity • 1980: Derek Humphry, a British journalist, founds Hemlock Society to promote euthanasia and assisted suicide for patients with advanced illness • 1992: Publication of Final Exit • 2003-4: Hemlock Society becomes Compassion and Choices Dr. -

Assisted Suicide

STRIPLING, A QUESTION OF MERCY, VOICES IN BIOETHICS, VOL. 1 (2015) A Question of Mercy: Contrasting Current and Past Perspectives on Physician- Assisted Suicide Mahala Yates Stripling, Ph.D. Keywords: right to die, assisted suicide The right-to-die debate was cast into the spotlight on November 1, 2014, when Brittany Maynard, a beautiful young California woman, took her own life by a doctor- prescribed lethal dose. Maynard, in her October 7, 2014, CNN article, “My Right to Death with Dignity at 29,” describes what led up to this decision. 2 Married just over a year, she and her husband were trying for a family. However, after months of suffering from debilitating headaches, she learned on New Year’s Day that she had brain cancer. “Our lives devolved into hospital stays, doctor consultations, and medical research,” she states in her article. Nine days after the diagnosis, she had a disfiguring partial craniotomy and partial resection of her temporal lobe to stop the growth of the tumor. When her aggressive tumor came back three months later, she was given a prognosis of six months to live. She opted out of full brain radiation that would leave her scalp covered with first-degree burns. “My quality of life, as I knew it, would be gone,” she admits in the CNN article. She ruled out hospice care because medication would not relieve her pain or forestall personality changes, including verbal, cognitive, and motor loss. Withholding treatment or removing life support—decisions made in America every day—were not an option for her. Whatever life she had left in her strong young body was mitigated by a deteriorating brain. -

Death with Dignity a Community Service Research Project Designed by Rutgers Jrs

Death with Dignity A community service research project designed by Rutgers Jrs. and Srs. to gain perspective on Euthanasia opinions at Rutgers University. Tag words: Euthanasia, Right to die, Physician assisted suicide, Terminally ill Authors: Cynthia Bengel, Olga Ivey, Arthur Omondi with Julie M. Fagan, Ph.D. Summary The group has been looking at the issue of euthanasia and whether it should be legalized in the state of NJ. Research was done on the history of euthanasia and on current global legislation. The service project was centered on doing a survey of the Rutgers University students to determine their views on the subject. A total of 273 students participated in the survey. 53.9% of respondents disagreed with the statement that euthanasia is always morally wrong. 49.8 % of the respondents disagreed with the statement that euthanasia should be illegal at least under all circumstances. 69.2 % of respondents agreed that the principal moral consideration about euthanasia is the question of whether the person freely chooses to die or not. Finally, 48.4 % of the respondents disagreed that actively killing someone is always morally worse than just letting them die. The results of this survey indicate that the student body is evenly divided between pro and anti euthanasia with a significant number being neutral on the subject. The Issue: Euthanasia The History of Euthanasia Euthanasia is a term derived from the Greek words Eu meaning “good” or “easy” and Thanatos meaning “death”. This term was used by Suetonius, a historian of the Roman Empire in the 2nd century AD. Euthanasia is also known as Mercy Killing or Assisted Suicide depending upon the circumstances. -

INFORMATIVE SPEECH TRANSCRIPT Euthanasia Laura Henderson Video Link 15.3 Speeches in Action Western Michigan University

INFORMATIVE SPEECH TRANSCRIPT Euthanasia Laura Henderson Video Link 15.3 Speeches in Action Western Michigan University Imagine you are unable to get out of bed, to eat, unassisted. Needing Notice how this attention another to clothe and bathe you day in and day out. Is that living? When getter uses rhetorical it’s your time to go, would that be dying with dignity? Let’s say you have a questions to draw the chronic illness and you are in extreme physical pain. Wouldn’t you want the audience in. right to ask your doctor to end your suffering? Or is that treading too far? Welcome to the debate of euthanasia. Today I will discuss the history and argumentation of assisted suicide. This is a statement of the general topic and purpose of the presentation. Assisted suicide, also known as euthanasia, is a hot-button issue that was brought into the light by Dr. Jack Kevorkian. Dr. Kevorkian was a controversial activist who tried to legalize assisted suicide under the argument that every- In this section, Laura shows one deserves a humane death. There had been much debate on the issue, the importance of the topic. and our legislatures have explored what the practice entails and the moral implications of assisted suicide. However, it is still illegal in all of the United States. But Physician Aid in Dying or PAD is legal in Washington, Oregon, and Montana. The difference is that euthanasia involves a third party to adminis- ter the dose, whereas PAD leaves it up to the patient to take it. -

The Role of a Physician in End-Of-Life Stages of Their Patients

The Idea of an Essay Volume 1 Reflecting on Rockwell, Contending for Cursive, and 22 Other Compositions Article 23 September 2014 The Role of a Physician in End-of-Life Stages of Their Patients David M. Anson Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/idea_of_an_essay Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Anson, David M. (2014) "The Role of a Physician in End-of-Life Stages of Their Patients," The Idea of an Essay: Vol. 1 , Article 23. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/idea_of_an_essay/vol1/iss1/23 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English, Literature, and Modern Languages at DigitalCommons@Cedarville. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Idea of an Essay by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Anson: The Role of a Physician in End-of-Life Stages of Their Patients “The Role of a Physician in End-of-Life Stages of Their Patients,” by David Anson Instructor’s Note It can be risky to select a hot button topic such as capital punishment, gun control, or abortion because one cannot generally join such a wide and vast written conversation with any kind of authority in such a limited number of pages as a typical essay. Yet in this persuasive essay, David Anson is able to tackle the vast topic of euthanasia because he narrows it and focuses only on the physician’s role. What do you think about David’s choice to begin his essay with a hypothetical story? What do you think works well in his conclusion? How could his conclusion be improved upon? Writer’s Biography David Anson is a freshman Biology major from southern Illinois. -

Assisted Suicide Advocate Dr. Jack Kevorkian Dies

ASSISTED SUICIDE ADVOCATE DR. JACK KEVORKIAN DIES Dr. Jack Kevorkian, assisted suicide crusader, died at age 83 in a hospital in Detroit on June 3, 2011. Kevorkian was known as “Dr. Death” since he killed or helped some 130 people commit suicide. A study of the deaths of 69 persons whom Kevorkian assisted to commit suicide in Oakland County, Michigan from 1990‐1998 found that 75% were not terminally ill, and five revealed no anatomical disease at autopsy. Dr. Kevorkian once spontaneously told a CNN interviewer, “The single worst moment of my life … was the moment I was born.” In April, 1999, Dr. Kevorkian was convicted of killing Thomas Youk, a victim of Lou Gehrig’s disease, by lethal injection. The event was shown on the CBS television show “60 Minutes.” Kevorkian was sentenced to 10 to 25 years in prison, but was released in 2007, claiming failing health. Unfortunately, Dr. Kevorkian’s place appears to have been taken by Dr. Lawrence Egbert, dubbed “The New Doctor Death” by Newsweek magazine. Dr. Egbert says that as the medical director of the Final Exit Network, he helped “direct the deaths of nearly 300 people across the country.” The Final Exit Network instructs people how to commit suicide so that they will appear to have died from natural causes. Dr. Egbert was criminally charged in Arizona and Georgia for his role as medical director of the Final Exit Network. Egbert was cleared of all charges in the Arizona case, while the Georgia case is still pending. Some suggest that with the “Culture of Death” being well established by the abortion movement, and the “sanctity of life” norm being replaced by the “quality of life” in medical ethics, a “perfect storm” to further the assisted suicide‐euthanasia movement has developed.