National Association of Attorneys General Boxing Task Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ray Beltran Fights for a World Title and a New Life!

RAY BELTRAN FIGHTS FOR A WORLD TITLE AND A NEW LIFE! Friday, February 16 Grand Sierra Resort in Reno, Nevada Live on ESPN, ESPN Deportes and the ESPN App Undercard Features Egidijus Kavaliauskas Defending NABF Welterweight Belt Against Former World Champion David Avanesyan Plus Olympic Silver Medalist Shakur Stevenson Tickets Go On Sale Tomorrow! Wednesday, January 24, at 1 P.M. ET Reno, NV (January 23, 2018) -- World championship boxing returns the "Biggest Little City in the World," Reno Nevada! No. 1 world-rated lightweight contender RAY "Sugar" BELTRAN, fighting for his first world championship belt and his green card to stay in the U.S. with his family, will headline an all-action card on Friday, February 16, in the Grand Sierra Resort's Grand Theatre. Beltran (34-7-1, 21 KOs), from Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico, will be battling former world champion and current No. 2 world-rated contender PAULUS MOSES (39-3, 24 KOs), from Windhoek, Namibia, for the vacant World Boxing Organization (WBO) lightweight world title. The co-main event will feature undefeated NABF welterweight champion EGIDIJUS "The Mean Machine" KAVALIAUSKAS (18-0, 15 KOs), from Oxnard, Calif., by way of Kaunas, Lithuania, defending his title against former world champion DAVID "Ava" AVANESYAN (23-2-1, 11 KOs), of Pyatigorsk, Russia, in a 10-round battle of Top-10 world-rated contenders. Both title fights will be televised live and exclusively at 9 p.m. EST on ESPN and ESPN Deportes and stream live on the ESPN App at 7 p.m. EST. The championship event will also feature the return of 2016 Olympic silver medalist SHAKUR STEVENSON (4-0, 2 KOs), of Newark, NJ. -

Download Our Sports Law Brochure

ahead ofthegame Sports Law SECTION ROW SEAT 86 H 1 625985297547 Hitting home runs Building Synergies with Renowned Brands for a legendary brand Herrick created the framework Rebuilding the House that Ruth Built and template agreements Game Day Our Sports Law Group rallied Herrick’s that govern advertising, real estate, corporate and tax lawyers promotion and product to structure five separate bond financ- placement rights for stadium Herrick’s Sports Law Group began advising the New York Yankees in the early ings, totaling in excess of $1.5 billion, sponsors. We have also which laid the financial foundation helped the Yankees extend Smooth Ride for Season Ticket Licensees 1990s, right as they began their march into a new era of excellence, both for the new Yankee Stadium. Our their brand by forming Playing musical chairs with tens of thousands cross-disciplinary team also advised on innovative joint ventures for of sports fans is tricky. We co-designed on and off the field. For more than two decades, our lawyers have helped the a number of complex matters related to a wide range of products, with the Yankees a season ticket license world’s most iconic professional sports franchise form innovative joint ventures, the new Yankee Stadium’s lease including the best-selling program for obtaining the rights to seats and construction. New York Yankees cologne. at the new Yankee Stadium. unleash new revenue streams, finance and build the new Yankee Stadium, and maximize the value of the team’s content – all of which have contributed Sparking the Regional to a global brand that’s unparalleled in the history of professional sports. -

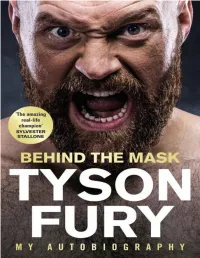

Behind the Mask: My Autobiography

Contents 1. List of Illustrations 2. Prologue 3. Introduction 4. 1 King for a Day 5. 2 Destiny’s Child 6. 3 Paris 7. 4 Vested Interests 8. 5 School of Hard Knocks 9. 6 Rolling with the Punches 10. 7 Finding Klitschko 11. 8 The Dark 12. 9 Into the Light 13. 10 Fat Chance 14. 11 Wild Ambition 15. 12 Drawing Power 16. 13 Family Values 17. 14 A New Dawn 18. 15 Bigger than Boxing 19. Illustrations 20. Useful Mental Health Contacts 21. Professional Boxing Record 22. Index About the Author Tyson Fury is the undefeated lineal heavyweight champion of the world. Born and raised in Manchester, Fury weighed just 1lb at birth after being born three months premature. His father John named him after Mike Tyson. From Irish traveller heritage, the“Gypsy King” is undefeated in 28 professional fights, winning 27 with 19 knockouts, and drawing once. His most famous victory came in 2015, when he stunned longtime champion Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA, IBF and WBO world heavyweight titles. He was forced to vacate the belts because of issues with drugs, alcohol and mental health, and did not fight again for more than two years. Most thought he was done with boxing forever. Until an amazing comeback fight with Deontay Wilder in December 2018. It was an instant classic, ending in a split decision tie. Outside of the ring, Tyson Fury is a mental health ambassador. He donated his million dollar purse from the Deontay Wilder fight to the homeless. This book is dedicated to the cause of mental health awareness. -

Steve Marantz; If the Other Sports Were...Xing

12/16/2015 STEVE MARANTZ; IF THE OTHER SPORTS WERE MORE LIKE BOXING . - The Boston Globe Archives STEVE MARANTZ; IF THE OTHER SPORTS WERE MORE LIKE BOXING . [FIRST Edition] Boston Globe (pre-1997 Fulltext) - Boston, Mass. Author: Marantz, Steve Date: May 16, 1982 Start Page: 1 Section: SPORTS Document Text In a period of a few months, boxing fans have been jilted by Cooney- Holmes, Hagler-Hearns, Leonard-Stafford and Weaver-Cobb. All of these were supposed to be major title fights before they became postponements. Cooney-Holmes is rescheduled for June 11, which leaves plenty of time for another postponement. Boxing fans no longer talk about who is going to win the big fight. They talk about when it will be postponed. Those less familiar with boxing must be terribly confused or amused. This is because boxing shares little common ground with other sports. Imagine if other sports were run like boxing: The Red Sox would have canceled their games with Kansas City this weekendbecause of Carl Yastrzemski's pulled groin. Dick Howser and the Royals' team physician would have demanded their own examination of Yaz. NFL Comr. Pete Rozelle would refuse to license the Patriots to play football because of their 2-14 record. Rozelle would say, "The Patriots have taken too many blows to the head. One more knockout could be fatal." The Patriots would change their name and go play in Rhode Island. George Steinbrenner would get the Yankees into the World Series by making a phone call to Mexico or Central America and buying them baseball's No. -

N.J. Boxing Hall of Fame Newsletter March 2017

The New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame Newsletter Volume 22 Issue 3 E-Mail Address: [email protected] March 2017 NEXT MEETING DATE - PRESIDENT - HENRY HASCUP 59 KIPP AVE, LODI, N.J. 07644 (1-973-471-2458) Posthumous participants being inducted are Thursday, Queens’ former middleweight and light Officials (Commission, Judges, Doctors heavyweight world champion Dick Tiger and Referees): Dr. Frank Doggett, Larry March 30th (60-19-3, 27 KOs), Brooklyn/Manhattan Hazzard Sr., Steve Smoger light heavyeight world champion Jose “Chegui” Torres (41-3-1, 29 KOs), and Media (Writers, Photographers, Artists, * The next meeting for the New Jersey Digital, Historians): Dave Bontempo, Jack Williamsburg middleweight world Boxing Hall of Fame will be on "KO JO" Obermayer, Bert Sugar champion “The Nonpareil”, Jack Thursday, March 30th, at the Faith Dempsey (51-4-11, 23 KOs). Reformed Church located at 95 Special Contributors: Ken Condon, Washington St. in Lodi, N.J. which is Non-participants heading into the Dennis Gomes, Bob Lee right at the corner of Washington and NYSBHOF are Queens’ International agent Prospect St., starting at 8:00 P.M. Don Majeski, Long Island matchmaker www.ACBHOF.com and through social Ron Katz, Manhattan manager Stan media (@ACBHOF on * At this meeting we will be announcing Hoffman and past Ring 8 Facebook/Instagram/Twitter). the 2017 Hall of Famers. president/NYSAC judge Bobby Bartels. * New Jersey Golden Glove Tournament * Our next Induction ceremonies will Posthumous non-participant inductees are March 25th - True Warriors Boxing be on Thursday, November 9th at Brooklyn boxing historian Hank Kaplan, Gym - 85 5th Ave Paterson @ 7:30 PM the Venetian in Garfield. -

Iron Boy Promotions and Top Rank Boxing Close Out

BOXING LEGEND AND UNDISPUTED HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPION KLITSCHKO TO TAKE ON UNDEFEATED JENNINGS LIVE AND EXCLUSIVE ON BOXNATION ON APRIL 25TH LONDON (March 27) – BoxNation are delighted to announce they will be screening undisputed heavyweight world champion Wladimir Klitschko’s April 25th fight with leading contender Bryant Jennings live and exclusive. The Ukrainian superstar has enjoyed a 10-year title reign at the top of boxing’s glamour division but will now put his WBA, WBO, IBF and IBO belts on the line against the undefeated Jennings at the legendary Madison Square Garden in New York. Klitschko will return to fight on US soil for the first time since February 2008, with the bout set to have high British interest with Manchester heavyweight Tyson Fury mandated to fight the winner later this year. Overcoming Jennings will be no easy task for 39-year-old Klitschko, with the Philadelphian, who has a three-inch reach advantage, hoping to become the first unified American heavyweight champion in more than 13 years. After building up an unbeaten record of 19 straight wins, 10 coming by way of knockout, Jennings is confident that he can finally become the man to dethrone Klitschko, who has won 63 fights, 53 by knockout, with only 3 losses – the last coming over a decade ago. “I do have great respect for Bryant Jennings and his achievements. He has good movement in the ring and good technique. I know this will be a tough challenge,” said Klitschko. “I am extremely happy to fight in New York City again. I had my first unification fight there and a lot of great heavyweight matches have taken place at Madison Square Garden. -

Syrians Fire on U.S. Jets Over Beirut ^ City Utilities TR IPO LI, Lebanon (U PI) - Syria-Backed Offensive to Crush His Refugee Camp

U — MANCHESTER HERALD. Wednesday. Nov. 9, 1983 GOP sees good signals Family MDs are MHS, East REAI from Tuesday elections a growing breed win openers ESTATE ... page 5 ... page 11 „ ... page 15 Rainy and windy Manchester, Conn. Thursday, Nov. 10, 1983 * 6Vs Rm, immediate occupancy tonight and Friday ^ Large lot with trees — See page 2 ilanrhratrr Single copy; 254 * Well insulated Mmlh * Unique fireplace * Formal dining room ^ Front to back living room * 3 bedrooms * Built in*s Syrians fire on U.S. jets over Beirut ^ City utilities TR IPO LI, Lebanon (U PI) - Syria-backed offensive to crush his refugee camp. How ever, Arafat 'appearing a Navy F-14 pilot reported what diately clear which side was * The Price Is Right! $89,900. Syrian gunners fired on U.S. F-U army in Lebanon. "Yesterday, a new Syrian div cheerful and confident said he appeared to be anti-aircraft fire. responsibile for violating a cease Tomcats over Beirut today and State-run Beirut radio said the ision — a mechanized division — thought he could hold out in Tripoli The aircraft was in no danger and fire between Arafat’s guerrilla Syrian tanks were rep ort^ ad- city of at least 150,000 people came began to enter the Lebanese and would stay until leaders of the continued its mission." force and the Palestinian rebels New Home in Vernon .vancing on Tripoli amid renewed under intensive artillery fire soon territory from the north. One city asked him to go which he said The spokesman would not say- trying to end his 14-year reign as Take advantage of the new CHFA Realty Co., Inc. -

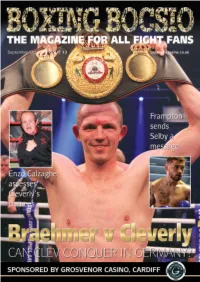

Bocsio Issue 13 Lr

ISSUE 13 20 8 BOCSIO MAGAZINE: MAGAZINE EDITOR Sean Davies t: 07989 790471 e: [email protected] DESIGN Mel Bastier Defni Design Ltd t: 01656 881007 e: [email protected] ADVERTISING 24 Rachel Bowes t: 07593 903265 e: [email protected] PRINT Stephens&George t: 01685 388888 WEBSITE www.bocsiomagazine.co.uk Boxing Bocsio is published six times a year and distributed in 22 6 south Wales and the west of England DISCLAIMER Nothing in this magazine may be produced in whole or in part Contents without the written permission of the publishers. Photographs and any other material submitted for 4 Enzo Calzaghe 22 Joe Cordina 34 Johnny Basham publication are sent at the owner’s risk and, while every care and effort 6 Nathan Cleverly 23 Enzo Maccarinelli 35 Ike Williams v is taken, neither Bocsio magazine 8 Liam Williams 24 Gavin Rees Ronnie James nor its agents accept any liability for loss or damage. Although 10 Brook v Golovkin 26 Guillermo 36 Fight Bocsio magazine has endeavoured 12 Alvarez v Smith Rigondeaux schedule to ensure that all information in the magazine is correct at the time 13 Crolla v Linares 28 Alex Hughes 40 Rankings of printing, prices and details may 15 Chris Sanigar 29 Jay Harris 41 Alway & be subject to change. The editor reserves the right to shorten or 16 Carl Frampton 30 Dale Evans Ringland ABC modify any letter or material submitted for publication. The and Lee Selby 31 Women’s boxing 42 Gina Hopkins views expressed within the 18 Oscar Valdez 32 Jack Scarrott 45 Jack Marshman magazine do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers. -

N.J. Boxing Hall of Fame Newsletter January 2017

The New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame Newsletter Volume 22 Issue 1 E-Mail Address: [email protected] January 2017 NEXT MEETING DATE - PRESIDENT - HENRY HASCUP 59 KIPP AVE, LODI, N.J. 07644 (1-973-471-2458) meeting. The 2017 Hall of Famers will be Posthumous non-participant inductees are Thursday, announced at the March meeting. Brooklyn boxing historian Hank Kaplan, Ring Notes: Long Island cut-man Al Gavin, Bronx January 26th *Ring # 25 has their monthly meetings at referee Arthur Donovan and New York the Senior Citizen Hall in Kearney. Contact City columnist Dan Parker. * The next meeting for the New Jersey President, Kathy Gatti, at 201-320-0874. Boxing Hall of Fame will be on Thursday, For more information contact President Bob January 26th, at the Faith Reformed *Ring # 8, of New York will have their Duffy, 164 Lindbergh St., Massapequa Church located at 95 Washington St. in next meeting on Thursday, February 23rd at Park, NY 11762 – 516-313-2304. the Plattduetsche Park Restaurant located at Lodi, N.J. which is right at the corner of Washington and Prospect St., starting at 1132 Hempstead Turnpike, Franklin Square, NY 11010. - Contact President Jack Hirsch * The Atlantic City Boxing Hall of Fame 8:00 P.M. May 26-28, 2017 at the famed Claridge at [email protected] 516-790-7592 Hotel at Park Place Boardwalk in Atlantic * My wife Joyce and I would like to wish City. Among those honored (all listed all of you and your loved ones a VERY * The New York State Boxing Hall of alphabetically): HAPPY NEW YEAR. -

Congratulations Class of 2010 from Thepastor

VOLUME VII NUMBER 3 INSIDE Class of 2010 Honors & Awards List of Colleges and Universities Valedictorian and Salutatorian Recognized 50th ANNIVERSARY YEAR Update CONGRATULATIONS CLASS OF 2010 from thePASTOR Dear Graduates and Friends of St. Raymond High School for Boys, The Golden Year has begun! We So we thank God for the blessings of the past 50 years and we thank opened the 50th Anniversary celebra- God for the blessings that continue to be showered down upon tion with a beautiful Mass in February the school—a very classy Graduation Mass and Ceremony for 159 attended by many of the brothers, students (all of whom have college, military and business plans), alums, present parents and students. progress in the building of our new extension, the Varsity Baseball Our student choir enhanced the beau- playoffs, the beginning of a new Lacrosse Team, the addition of two ty of the Mass, our alums were lectors De LaSalle Brothers for September, special generosity of over $4,000 and our students served at the altar. from the students to the people of Haiti and an incoming freshman The Mass was celebrated by ‘one of class of 204 students — all part of our Golden Anniversary and gold- our own’— Father Paul Waddell ‘76. He certainly entertained us en future here in the Bronx. with stories from the past. A reception followed in the Cafeteria and more great stories and happy memories were exchanged over cake Please know that you are welcome to visit the school, tour the build- and coffee. ing and inspect the new construction site. -

HOT from PACQUIAO - BRADLEY MEDIA CENTRAL! T-Minus 14 Days Edition

HOT FROM PACQUIAO - BRADLEY MEDIA CENTRAL! T-Minus 14 Days Edition HBO Sports Presents LEGACY ON THE LINE: FROM BRADLEY TO PACQUIAO Tonight! Saturday, March 26 at Midnight ET/PT Tim Dahlberg, Associated Press: "NoTrump Undercard Carries a Message with a Punch" http://hosted.ap.org/dynamic/stories/B/BOX_TIM_DAHLBERG?SITE=AP&SECTION=HOME&TEMPLATE=DEFAULT&CT IME=2016-03-24-02-46-33 Robert Morales, Los Angeles Daily News: "Timothy Bradley, Teddy Atlas Relationship So Strong It's Scary" http://www.dailynews.com/sports/20160322/timothy-bradley-teddy-atlas-relationship-so-strong-its-scary Lance Pugmire, Los Angeles Times: "Southland Boxer Oscar Valdez Has Manny Pacquiao- Timothy Bradley Card to Shine" http://www.latimes.com/sports/sportsnow/la-sp-sn-boxing-oscar-valdez-pacquiao-bradley-mgm-hbo-20160323-story.html Greg Bishop, Sports Illustrated: "Pacquiao, Roach Talk Upcoming Fight vs. Bradley, Future for Boxer" http://www.si.com/boxing/2016/03/24/manny-pacquiao-tim-bradley-freddie-roach-mayweather-olympics-philippines Dan Rafael, ESPN.com: "Abraham Deep Into Long Camp for Ramirez Defense" http://espn.go.com/blog/dan-rafael/post/_/id/15636/abraham-deep-into-long-camp-for-ramirez-defense Roy Luarca, The Philippine Inquirer: "Pacquiao 'In Great Shape,' Reaches Training Summit" http://sports.inquirer.net/209586/pacquiao-reaches-training-summit Nick Giongco, Manila Bulletin: "Pacquiao Eyes 21st Victory in U.S." http://www.mb.com.ph/pacquiao-eyes-21st-victory-in-us/ Abac Cordero, The Philippine Star: "Going Over 100 Rounds, Pacquiao Nears End of -

Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want to Share: an Analysis of Antitrust Issues Surrounding Boxing and Mixed Martial Arts and Ways to Improve Combat Sports

Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 5 8-1-2018 Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want To Share: An Analysis of Antitrust Issues Surrounding Boxing and Mixed Martial Arts and Ways to Improve Combat Sports Daniel L. Maschi Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel L. Maschi, Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want To Share: An Analysis of Antitrust Issues Surrounding Boxing and Mixed Martial Arts and Ways to Improve Combat Sports, 25 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 409 (2018). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol25/iss2/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\25-2\VLS206.txt unknown Seq: 1 26-JUN-18 12:26 Maschi: Million Dollar Babies Do Not Want To Share: An Analysis of Antitr MILLION DOLLAR BABIES DO NOT WANT TO SHARE: AN ANALYSIS OF ANTITRUST ISSUES SURROUNDING BOXING AND MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND WAYS TO IMPROVE COMBAT SPORTS I. INTRODUCTION Coined by some as the “biggest fight in combat sports history” and “the money fight,” on August 26, 2017, Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) mixed martial arts (MMA) superstar, Conor McGregor, crossed over to boxing to take on the biggest