The Twelfth Round: Will Boxing Save Itself?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden-Boy-V-Haymon-Full-Summary

Case 2:15-cv-03378-JFW-MRW Document 339 Filed 01/26/17 Page 1 of 24 Page ID #:22715 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA CIVIL MINUTES -- GENERAL Case No. CV 15-3378-JFW (MRWx) Date: January 26, 2017 Title: Golden Boy Promotions LLC, et al. -v- Alan Haymon, et al. PRESENT: HONORABLE JOHN F. WALTER, UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE Shannon Reilly None Present Courtroom Deputy Court Reporter ATTORNEYS PRESENT FOR PLAINTIFFS: ATTORNEYS PRESENT FOR DEFENDANTS: None None PROCEEDINGS (IN CHAMBERS): ORDER GRANTING DEFENDANT ALAN HAYMON’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT [filed 10/31/2016; Docket Nos. 147, 310]; ORDER GRANTING DEFENDANTS ALAN HAYMON DEVELOPMENT, INC., HAYMON BOXING LLC, HAYMON BOXING MANAGEMENT, HAYMON HOLDINGS LLC, AND HAYMON SPORTS LLC’S MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT [filed 10/31/2016; Docket Nos. 158, 311] On October 31, 2016, Defendant Alan Haymon (“Haymon”) filed a Motion for Summary Judgment [Docket Nos. 147, 310]. On November 9, 2016, Plaintiffs Golden Boy Promotions, LLC, Golden Boy Promotions, Inc., and Bernard Hopkins (collectively, “Plaintiffs”) filed their Opposition [Docket Nos. 212, 215, 255]. On November 14, 2016, Haymon filed a Reply [Docket Nos. 270, 272, 274]. On October 31, 2016, Defendants Alan Haymon Development, Inc., Haymon Boxing LLC, Haymon Boxing Management, Haymon Holdings LLC, and Haymon Sports LLC (collectively, the “Haymon Entities”) filed a Motion for Summary Judgment [Docket Nos. 158, 311]. On November 9, 2016, Plaintiffs filed their Opposition [Docket Nos. 217, 218, 256]. On November 14, 2016, the Haymon Entities filed a Reply [Docket Nos. 271, 275]. Pursuant to Rule 78 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and Local Rule 7-15, the Court found these matters appropriate for submission on the papers without oral argument. -

Comedy Taken Seriously the Mafia’S Ties to a Murder

MONDAY Beauty and the Beast www.annistonstar.com/tv The series returns with an all-new episode that finds Vincent (Jay Ryan) being TVstar arrested for May 30 - June 5, 2014 murder. 8 p.m. on The CW TUESDAY Celebrity Wife Swap Rock prince Dweezil Zappa trades his mate for the spouse of a former MLB outfielder. 9 p.m. on ABC THURSDAY Elementary Watson (Lucy Liu) and Holmes launch an investigation into Comedy Taken Seriously the mafia’s ties to a murder. J.B. Smoove is the dynamic new host of NBC’s 9:01 p.m. on CBS standup comedy competition “Last Comic Standing,” airing Mondays at 7 p.m. Get the deal of a lifetime for Home Phone Service. * $ Cable ONE is #1 in customer satisfaction for home phone.* /mo Talk about value! $25 a month for life for Cable ONE Phone. Now you’ve got unlimited local calling and FREE 25 long distance in the continental U.S. All with no contract and a 30-Day Money-Back Guarantee. It’s the best FOR LIFE deal on the most reliable phone service. $25 a month for life. Don’t wait! 1-855-CABLE-ONE cableone.net *Limited Time Offer. Promotional rate quoted good for eligible residential New Customers. Existing customers may lose current discounts by subscribing to this offer. Changes to customer’s pre-existing services initiated by customer during the promotional period may void Phone offer discount. Offer cannot be combined with any other discounts or promotions and excludes taxes, fees and any equipment charges. -

Tickets Delayed Relocation

TICKETS RELOCATION DELAYED Digital dismissal system Merritt encourages bypass Whiteville High School’s for traffic violations businesses to move downtown Legion Stadium field house going online. when widening begins. project running late. uuSEE 4A uuSEE 2A uuSEE 3A The News Reporter Published since 1890 every Monday and Thursday for the County of Columbus and her people. WWW.NRCOLUMBUS.COM Monday, July 25, 2016 75 CENTS SLICE TWICE ... SLICE THRICE ... SLICE NICE WESTERN PRONG PRECINCT MOVE IN MONDAY MEETING Elections board to consider new voting machines By Allen Turner [email protected] The Columbus County Board of Elections will meet to- day at 5 p.m. to consider purchasing new voting equipment to be used throughout the county. A new polling site for the Western Prong precinct is also under consideration. The board is expected to approve the purchase of 42 new voting machines at $245,000. The new machines would be in use by the November General Election. Michelle Mrozkowski of New Bern-based vendor Print- Elect demonstrated the new voting machines Friday for Board of Elections members and the public. The DS200 precinct scanner and tabulator would re- place older machines in use in Columbus County since 2006. When a voter casts his or her ballot, the new machine will be able to detect whether the voter has undervoted (by not voting in all races or by not voting for as many candidates as possible in a race) or overvoted (by voting for too many candidates in a race). The voter will be alerted by the machine and given the choice of either casting the ballot as marked or returning Staff photo by ALLEN TURNER A machete-weilding volunteer makes short work of preparing watermelon samples during Saturday’s N.C. -

Ray Beltran Fights for a World Title and a New Life!

RAY BELTRAN FIGHTS FOR A WORLD TITLE AND A NEW LIFE! Friday, February 16 Grand Sierra Resort in Reno, Nevada Live on ESPN, ESPN Deportes and the ESPN App Undercard Features Egidijus Kavaliauskas Defending NABF Welterweight Belt Against Former World Champion David Avanesyan Plus Olympic Silver Medalist Shakur Stevenson Tickets Go On Sale Tomorrow! Wednesday, January 24, at 1 P.M. ET Reno, NV (January 23, 2018) -- World championship boxing returns the "Biggest Little City in the World," Reno Nevada! No. 1 world-rated lightweight contender RAY "Sugar" BELTRAN, fighting for his first world championship belt and his green card to stay in the U.S. with his family, will headline an all-action card on Friday, February 16, in the Grand Sierra Resort's Grand Theatre. Beltran (34-7-1, 21 KOs), from Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico, will be battling former world champion and current No. 2 world-rated contender PAULUS MOSES (39-3, 24 KOs), from Windhoek, Namibia, for the vacant World Boxing Organization (WBO) lightweight world title. The co-main event will feature undefeated NABF welterweight champion EGIDIJUS "The Mean Machine" KAVALIAUSKAS (18-0, 15 KOs), from Oxnard, Calif., by way of Kaunas, Lithuania, defending his title against former world champion DAVID "Ava" AVANESYAN (23-2-1, 11 KOs), of Pyatigorsk, Russia, in a 10-round battle of Top-10 world-rated contenders. Both title fights will be televised live and exclusively at 9 p.m. EST on ESPN and ESPN Deportes and stream live on the ESPN App at 7 p.m. EST. The championship event will also feature the return of 2016 Olympic silver medalist SHAKUR STEVENSON (4-0, 2 KOs), of Newark, NJ. -

Georges Carpentier Sur La Riviera En Février 1912, Stéphane Hadjeras

Georges Carpentier sur la Riviera Février 1912 Stéphane Hadjeras Doctorant en histoire Contemporaine - Université de Franche Comté A la fin de l’année 1911, Georges Carpentier n’avait même pas 18 ans et pourtant sa carrière de pugiliste semblait avoir pris un tournant majeur pour au moins deux raisons. D’abord le 23 octobre, devant un public londonien médusé, il devint, en infligeant au King’s Hall une sévère défaite au britannique Young Joseph, le premier champion d’Europe français. Puis, le 13 décembre, au Cirque de Paris, à la grande surprise des journalistes sportifs et autres admirateurs du noble art, il battit aux points le célèbre « fighter » américain, ancien champion du monde des poids welters, Harry Lewis. Accueilli, en véritable héros à son retour de Londres, par plus de 3000 personnes à la Gare du Nord, plébiscité par la presse sportive après son triomphe sur l’américain, ovationné par un Paris mondain de plus en plus féru de boxe, Georges Carpentier fut en passe de devenir en ce début d’année 1912 l’idole de toute une nation. Ainsi, l’annonce de son combat contre le britannique Jim Sullivan, le 29 février, à Monte Carlo, pour le titre de champion d’Europe des poids moyens, apparut de plus en plus comme une confirmation de l’inéluctable ascension du « petit prodige »1 vers le titre mondial. Monte Carlo. L’évocation de ce lieu provoqua chez le champion un début d’évasion : « La Cote d’Azur, la mer bleue, le ciel plus bleu encore, les palmiers, les arbres avec des oranges ! J’avais vu des affiches et des prospectus. -

Dec 2004 Current List

Fighter Opponent Result / RoundsUnless specifiedDate fights / Time are not ESPN NetworkClassic, Superbouts. Comments Ali Al "Blue" Lewis TKO 11 Superbouts Ali fights his old sparring partner Ali Alfredo Evangelista W 15 Post-fight footage - Ali not in great shape Ali Archie Moore TKO 4 10 min Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 ABC Commentary by Cossell - Some break up in picture Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 British CC Ali gets cut Ali Brian London TKO 3 B&W Ali in his prime Ali Buster Mathis W 12 Commentary by Cossell - post-fight footage Ali Chuck Wepner KO 15 Classic Sports Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 B&W Commentary by Don Dunphy - Ali in his prime Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 Classic Sports Ali in his prime Ali Doug Jones W 10 Jones knows how to fight - a tough test for Cassius Ali Earnie Shavers W 15 Brutal battle - Shavers rocks Ali with right hand bombs Ali Ernie Terrell W 15 Feb, 1967 Classic Sports Commentary by Cossell Ali Floyd Patterson i TKO 12 22-Nov-1965 B&W Ali tortures Floyd Ali Floyd Patterson ii TKO 7 Superbouts Commentary by Cossell Ali George Chuvalo i W 15 Classic Sports Ali has his hands full with legendary tough Canadian Ali George Chuvalo ii W 12 Superbouts In shape Ali battles in shape Chuvalo Ali George Foreman KO 8 Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Gorilla Monsoon Wrestling Ali having fun Ali Henry Cooper i TKO 5 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Henry Cooper ii TKO 6 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only - extensive pre-fight Ali Ingemar Johansson Sparring 5 min B&W Silent audio - Sparring footage Ali Jean Pierre Coopman KO 5 Rumor has it happy Pierre drank before the bout Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 Superbouts Ali at his relaxed best Ali Jerry Quarry i TKO 3 Ali cuts up Quarry Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jimmy Ellis TKO 12 Ali beats his old friend and sparring partner Ali Jimmy Young W 15 Ali is out of shape and gets a surprise from Young Ali Joe Bugner i W 12 Incomplete - Missing Rds. -

Behind the Mask: My Autobiography

Contents 1. List of Illustrations 2. Prologue 3. Introduction 4. 1 King for a Day 5. 2 Destiny’s Child 6. 3 Paris 7. 4 Vested Interests 8. 5 School of Hard Knocks 9. 6 Rolling with the Punches 10. 7 Finding Klitschko 11. 8 The Dark 12. 9 Into the Light 13. 10 Fat Chance 14. 11 Wild Ambition 15. 12 Drawing Power 16. 13 Family Values 17. 14 A New Dawn 18. 15 Bigger than Boxing 19. Illustrations 20. Useful Mental Health Contacts 21. Professional Boxing Record 22. Index About the Author Tyson Fury is the undefeated lineal heavyweight champion of the world. Born and raised in Manchester, Fury weighed just 1lb at birth after being born three months premature. His father John named him after Mike Tyson. From Irish traveller heritage, the“Gypsy King” is undefeated in 28 professional fights, winning 27 with 19 knockouts, and drawing once. His most famous victory came in 2015, when he stunned longtime champion Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA, IBF and WBO world heavyweight titles. He was forced to vacate the belts because of issues with drugs, alcohol and mental health, and did not fight again for more than two years. Most thought he was done with boxing forever. Until an amazing comeback fight with Deontay Wilder in December 2018. It was an instant classic, ending in a split decision tie. Outside of the ring, Tyson Fury is a mental health ambassador. He donated his million dollar purse from the Deontay Wilder fight to the homeless. This book is dedicated to the cause of mental health awareness. -

Two-Division World Champion Michael Spinks Confirmed for Sixth Annual Box Fan Expo, During Cinco De Mayo Weekend, Saturday May 2, in Las Vegas

Two-Division World Champion Michael Spinks Confirmed for Sixth Annual Box Fan Expo, During Cinco de Mayo Weekend, Saturday May 2, in Las Vegas Las Vegas (February 20, 2020) – Two-division world champion Michael Spinks has confirmed that he will appear at the sixth annual Box Fan Expo on Saturday, May 2, 2020, at the Cox Pavilion in Las Vegas from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Spinks will hold a Meet & Greet with his fans at his booth during the fan event held over the Cinco De Mayo weekend. The Box Fan Expo is an annual fan event that coincides with some of the sports’ legendary, classic fights in Las Vegas, including Mayweather vs. Maidana II, Mayweather vs. Berto, Canelo vs. Chavez Jr., Canelo vs. GGG II, and Canelo vs. Jacobs. Centered in boxing’s longtime home – Las Vegas – this year’s Expo is a must-do for fight fans coming in for this legendary weekend, with dozens of professional fighters, promoters, and companies involved in the boxing industry. The Expo is the largest and only Boxing Fan Expo held in the United States. http://boxfanexpo.com- @BoxFanExpo Tickets to the Box Fan Expo are available online at: https://bitly.com/BoxingExpo2020 Spinks will make his second appearance at this years’ Expo and will be signing gloves, photos, personal items and memorabilia. Spinks will also have merchandise on sale at his booth, and fans will also have an opportunity to take pictures with this boxing legend also known as “Jinx.” About Michael Spinks Spinks is a two-division world champion, having held the undisputed light heavyweight title from 1983 to 1985, and the lineal heavyweight title from 1985 to 1988. -

The Safety of BKB in a Modern Age

The Safety of BKB in a modern age Stu Armstrong 1 | Page The Safety of Bare Knuckle Boxing in a modern age Copyright Stu Armstrong 2015© www.stuarmstrong.com Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 The Author .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Why write this paper? ......................................................................................................................... 3 The Safety of BKB in a modern age ................................................................................................... 3 Pugilistic Dementia ............................................................................................................................. 4 The Marquis of Queensbury Rules’ (1867) ......................................................................................... 4 The London Prize Ring Rules (1743) ................................................................................................. 5 Summary ............................................................................................................................................. 7 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................................ 8 2 | Page The Safety of Bare Knuckle Boxing in a modern age Copyright Stu Armstrong 2015© -

Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity

Copyright By Omar Gonzalez 2019 A History of Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in History 2019 A Historyof Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez This thesishas beenacce ted on behalf of theDepartment of History by their supervisory CommitteeChair 6 Kate Mulry, PhD Cliona Murphy, PhD DEDICATION To my wife Berenice Luna Gonzalez, for her love and patience. To my family, my mother Belen and father Jose who have given me the love and support I needed during my academic career. Their efforts to raise a good man motivates me every day. To my sister Diana, who has grown to be a smart and incredible young woman. To my brother Mario, whose kindness reaches the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada and who has been an inspiration in my life. And to my twin brother Miguel, his incredible support, his wisdom, and his kindness have not only guided my life but have inspired my journey as a historian. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is a result of over two years of research during my time at CSU Bakersfield. First and foremost, I owe my appreciation to Dr. Stephen D. Allen, who has guided me through my challenging years as a graduate student. Since our first encounter in the fall of 2016, his knowledge of history, including Mexican boxing, has enhanced my understanding of Latin American History, especially Modern Mexico. -

Boxing Edition

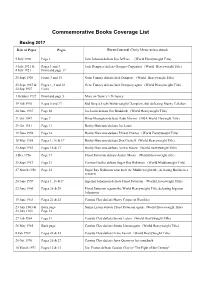

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

FA 2010 Resource Pack

Frantic Assembly and the National Theatre of Scotland present Beautiful Burnout By Bryony Lavery A Comprehensive Guide for students (aged 14+), teachers & arts educationalists By Scott Graham Contents 3 Introduction 4 Why Boxing? 4 Why Beautiful Burnout? 5 Why Underworld? 5 Why Bryony Lavery? 5 Essays 5 Research and Development 6 The danger of cliché and the need for authenticity 7 Damage: The Elephant in the room 8 Bloodsport or Noble Art? 9 Creating the image 10 The Training 12 The Research - the gyms, lists, DVDs, books, interviews 13 The Warm Ups - Flipping what we know - Explosive before stretches 13 Fathers and Sons - the boxing family 14 The Use of Film 15 The Referee 17 God and Man 17 The Danger of Unison 17 Scenes 17 The Fight - 'Beautiful Burnout' 19 Kittens 19 Wraps 20 Scribble (inc.This Is Your Scribble!) 21 One Punch 22 Catch Up 23 Referees 24 Exercises 24 Head Smacks 24 Trainer and Boxer 25 Bibliography Photos by Gavin Evans Front cover photo by Ela Wlodarczyk Introduction This resource pack is written to enhance the experience of watching Beautiful Burnout, to hopefully give some insight into the creative process and maybe even answer some questions. What you will not find too much of is work sheets and references to examination bodies and attainment targets. The reason behind this is that we hope this pack can be both informative and enjoyable. Teachers know their classes better than we do and can take any inspiration found in here and apply it within the classroom better than we can by suggesting an exercise.