Rethinking the Use of Antitrust Law in Combat Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tickets Delayed Relocation

TICKETS RELOCATION DELAYED Digital dismissal system Merritt encourages bypass Whiteville High School’s for traffic violations businesses to move downtown Legion Stadium field house going online. when widening begins. project running late. uuSEE 4A uuSEE 2A uuSEE 3A The News Reporter Published since 1890 every Monday and Thursday for the County of Columbus and her people. WWW.NRCOLUMBUS.COM Monday, July 25, 2016 75 CENTS SLICE TWICE ... SLICE THRICE ... SLICE NICE WESTERN PRONG PRECINCT MOVE IN MONDAY MEETING Elections board to consider new voting machines By Allen Turner [email protected] The Columbus County Board of Elections will meet to- day at 5 p.m. to consider purchasing new voting equipment to be used throughout the county. A new polling site for the Western Prong precinct is also under consideration. The board is expected to approve the purchase of 42 new voting machines at $245,000. The new machines would be in use by the November General Election. Michelle Mrozkowski of New Bern-based vendor Print- Elect demonstrated the new voting machines Friday for Board of Elections members and the public. The DS200 precinct scanner and tabulator would re- place older machines in use in Columbus County since 2006. When a voter casts his or her ballot, the new machine will be able to detect whether the voter has undervoted (by not voting in all races or by not voting for as many candidates as possible in a race) or overvoted (by voting for too many candidates in a race). The voter will be alerted by the machine and given the choice of either casting the ballot as marked or returning Staff photo by ALLEN TURNER A machete-weilding volunteer makes short work of preparing watermelon samples during Saturday’s N.C. -

Ray Beltran Fights for a World Title and a New Life!

RAY BELTRAN FIGHTS FOR A WORLD TITLE AND A NEW LIFE! Friday, February 16 Grand Sierra Resort in Reno, Nevada Live on ESPN, ESPN Deportes and the ESPN App Undercard Features Egidijus Kavaliauskas Defending NABF Welterweight Belt Against Former World Champion David Avanesyan Plus Olympic Silver Medalist Shakur Stevenson Tickets Go On Sale Tomorrow! Wednesday, January 24, at 1 P.M. ET Reno, NV (January 23, 2018) -- World championship boxing returns the "Biggest Little City in the World," Reno Nevada! No. 1 world-rated lightweight contender RAY "Sugar" BELTRAN, fighting for his first world championship belt and his green card to stay in the U.S. with his family, will headline an all-action card on Friday, February 16, in the Grand Sierra Resort's Grand Theatre. Beltran (34-7-1, 21 KOs), from Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico, will be battling former world champion and current No. 2 world-rated contender PAULUS MOSES (39-3, 24 KOs), from Windhoek, Namibia, for the vacant World Boxing Organization (WBO) lightweight world title. The co-main event will feature undefeated NABF welterweight champion EGIDIJUS "The Mean Machine" KAVALIAUSKAS (18-0, 15 KOs), from Oxnard, Calif., by way of Kaunas, Lithuania, defending his title against former world champion DAVID "Ava" AVANESYAN (23-2-1, 11 KOs), of Pyatigorsk, Russia, in a 10-round battle of Top-10 world-rated contenders. Both title fights will be televised live and exclusively at 9 p.m. EST on ESPN and ESPN Deportes and stream live on the ESPN App at 7 p.m. EST. The championship event will also feature the return of 2016 Olympic silver medalist SHAKUR STEVENSON (4-0, 2 KOs), of Newark, NJ. -

Download Our Sports Law Brochure

ahead ofthegame Sports Law SECTION ROW SEAT 86 H 1 625985297547 Hitting home runs Building Synergies with Renowned Brands for a legendary brand Herrick created the framework Rebuilding the House that Ruth Built and template agreements Game Day Our Sports Law Group rallied Herrick’s that govern advertising, real estate, corporate and tax lawyers promotion and product to structure five separate bond financ- placement rights for stadium Herrick’s Sports Law Group began advising the New York Yankees in the early ings, totaling in excess of $1.5 billion, sponsors. We have also which laid the financial foundation helped the Yankees extend Smooth Ride for Season Ticket Licensees 1990s, right as they began their march into a new era of excellence, both for the new Yankee Stadium. Our their brand by forming Playing musical chairs with tens of thousands cross-disciplinary team also advised on innovative joint ventures for of sports fans is tricky. We co-designed on and off the field. For more than two decades, our lawyers have helped the a number of complex matters related to a wide range of products, with the Yankees a season ticket license world’s most iconic professional sports franchise form innovative joint ventures, the new Yankee Stadium’s lease including the best-selling program for obtaining the rights to seats and construction. New York Yankees cologne. at the new Yankee Stadium. unleash new revenue streams, finance and build the new Yankee Stadium, and maximize the value of the team’s content – all of which have contributed Sparking the Regional to a global brand that’s unparalleled in the history of professional sports. -

Dec 2004 Current List

Fighter Opponent Result / RoundsUnless specifiedDate fights / Time are not ESPN NetworkClassic, Superbouts. Comments Ali Al "Blue" Lewis TKO 11 Superbouts Ali fights his old sparring partner Ali Alfredo Evangelista W 15 Post-fight footage - Ali not in great shape Ali Archie Moore TKO 4 10 min Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 ABC Commentary by Cossell - Some break up in picture Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 British CC Ali gets cut Ali Brian London TKO 3 B&W Ali in his prime Ali Buster Mathis W 12 Commentary by Cossell - post-fight footage Ali Chuck Wepner KO 15 Classic Sports Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 B&W Commentary by Don Dunphy - Ali in his prime Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 Classic Sports Ali in his prime Ali Doug Jones W 10 Jones knows how to fight - a tough test for Cassius Ali Earnie Shavers W 15 Brutal battle - Shavers rocks Ali with right hand bombs Ali Ernie Terrell W 15 Feb, 1967 Classic Sports Commentary by Cossell Ali Floyd Patterson i TKO 12 22-Nov-1965 B&W Ali tortures Floyd Ali Floyd Patterson ii TKO 7 Superbouts Commentary by Cossell Ali George Chuvalo i W 15 Classic Sports Ali has his hands full with legendary tough Canadian Ali George Chuvalo ii W 12 Superbouts In shape Ali battles in shape Chuvalo Ali George Foreman KO 8 Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Gorilla Monsoon Wrestling Ali having fun Ali Henry Cooper i TKO 5 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Henry Cooper ii TKO 6 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only - extensive pre-fight Ali Ingemar Johansson Sparring 5 min B&W Silent audio - Sparring footage Ali Jean Pierre Coopman KO 5 Rumor has it happy Pierre drank before the bout Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 Superbouts Ali at his relaxed best Ali Jerry Quarry i TKO 3 Ali cuts up Quarry Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jimmy Ellis TKO 12 Ali beats his old friend and sparring partner Ali Jimmy Young W 15 Ali is out of shape and gets a surprise from Young Ali Joe Bugner i W 12 Incomplete - Missing Rds. -

Premier Boxing Champions on Espn Media Conference Call Transcript with Keith Thurman & Luis Collazo

PREMIER BOXING CHAMPIONS ON ESPN MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL TRANSCRIPT WITH KEITH THURMAN & LUIS COLLAZO Kelly Swanson Thanks everybody for calling in. We are talking today about the inaugural Premier Boxing Champions on ESPN event. The series is about to start on Saturday July 11 with a fantastic fight and two really great televised fights but today we're talking about the main event which features the welterweight showdown between undefeated knockout artist Keith "One Time" Thurman and former world champion Luis Collazo. The televised coverage begins on ESPN at 9 pm ET/6 pm PT and that will start with a matchup between undefeated rising star Tony Harrison against Willie Nelson that's going to be a barn burner. Tickets for the live event, which will take place July 11 at the USF Sun Dome in Tampa, Florida are still available. The event is promoted by Warriors Boxing. You can find the tickets through Ticketmaster or visiting the Sun Dome box office. We're going to get right to the fighters today which is always pleasant for both the fighters and the media. I'm going to first introduce Luis Collazo. His record is 36 and 6 with 19 knockouts. He's from Brooklyn, a former world champ and Luis has definitely faced some of the bigger names in boxing such as Shane Mosley, Ricky Hatton, Victor Ortiz and Andre Berto. So Luis do you want to just say hello and make an opening statement and then I'll introduce Keith, he can make an opening statement and then we'll turn it over to questions for both guys. -

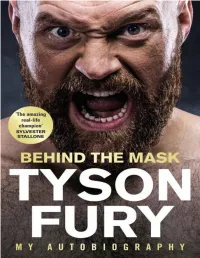

Behind the Mask: My Autobiography

Contents 1. List of Illustrations 2. Prologue 3. Introduction 4. 1 King for a Day 5. 2 Destiny’s Child 6. 3 Paris 7. 4 Vested Interests 8. 5 School of Hard Knocks 9. 6 Rolling with the Punches 10. 7 Finding Klitschko 11. 8 The Dark 12. 9 Into the Light 13. 10 Fat Chance 14. 11 Wild Ambition 15. 12 Drawing Power 16. 13 Family Values 17. 14 A New Dawn 18. 15 Bigger than Boxing 19. Illustrations 20. Useful Mental Health Contacts 21. Professional Boxing Record 22. Index About the Author Tyson Fury is the undefeated lineal heavyweight champion of the world. Born and raised in Manchester, Fury weighed just 1lb at birth after being born three months premature. His father John named him after Mike Tyson. From Irish traveller heritage, the“Gypsy King” is undefeated in 28 professional fights, winning 27 with 19 knockouts, and drawing once. His most famous victory came in 2015, when he stunned longtime champion Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA, IBF and WBO world heavyweight titles. He was forced to vacate the belts because of issues with drugs, alcohol and mental health, and did not fight again for more than two years. Most thought he was done with boxing forever. Until an amazing comeback fight with Deontay Wilder in December 2018. It was an instant classic, ending in a split decision tie. Outside of the ring, Tyson Fury is a mental health ambassador. He donated his million dollar purse from the Deontay Wilder fight to the homeless. This book is dedicated to the cause of mental health awareness. -

Steve Marantz; If the Other Sports Were...Xing

12/16/2015 STEVE MARANTZ; IF THE OTHER SPORTS WERE MORE LIKE BOXING . - The Boston Globe Archives STEVE MARANTZ; IF THE OTHER SPORTS WERE MORE LIKE BOXING . [FIRST Edition] Boston Globe (pre-1997 Fulltext) - Boston, Mass. Author: Marantz, Steve Date: May 16, 1982 Start Page: 1 Section: SPORTS Document Text In a period of a few months, boxing fans have been jilted by Cooney- Holmes, Hagler-Hearns, Leonard-Stafford and Weaver-Cobb. All of these were supposed to be major title fights before they became postponements. Cooney-Holmes is rescheduled for June 11, which leaves plenty of time for another postponement. Boxing fans no longer talk about who is going to win the big fight. They talk about when it will be postponed. Those less familiar with boxing must be terribly confused or amused. This is because boxing shares little common ground with other sports. Imagine if other sports were run like boxing: The Red Sox would have canceled their games with Kansas City this weekendbecause of Carl Yastrzemski's pulled groin. Dick Howser and the Royals' team physician would have demanded their own examination of Yaz. NFL Comr. Pete Rozelle would refuse to license the Patriots to play football because of their 2-14 record. Rozelle would say, "The Patriots have taken too many blows to the head. One more knockout could be fatal." The Patriots would change their name and go play in Rhode Island. George Steinbrenner would get the Yankees into the World Series by making a phone call to Mexico or Central America and buying them baseball's No. -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04Rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O. BOX 377 JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (ARGENTINA) MARACAY 2101 -A ALAN KIM (KOREA) EDO. ARAGUA - VENEZUELA SHIGERU KOJIMA (JAPAN) PHONE: + (58-244) 663-1584 VICE CHAIRMAN GONZALO LOPEZ SILVERO (USA) + (58-244) 663-3347 GEORGE MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORS FAX: + (58-244) 663-3177 E-mail: [email protected] SEBASTIAN CONTURSI (ARGENTINA) Web site: www.wbaonline.com UNIFIED CHAMPION: JEAN MARC MORMECK FRA World Champion: JOHN RUIZ USA Won Title: 04-02-05 World Champion: FABRICE TIOZZO FRA Won Title: 12-13 -03 Last Defense: Won Title: 03-20- 04 Last Mandatory: 04-30 -05 _________________________________ Last Mandatory: 02-26- 05 Last Defense: 04-30 -05 World C hampion: VACANT Last Defense: 02-26- 05 WBC: VITALI KLITSCHKO - IBF: CHRIS BYRD WBC: JEAN MARC MORMECK- IBF: O’NEIL BELL WBC: THOMAS ADAMEK - IBF: CLINTON WOODS WBO : LAMON BREWSTER WBO : JOHNNY NELSON WBO : ZSOLT ERDEI 1. NICOLAY VALUEV (OC) RUS 1. VALERY BRUDOV RUS 1. JORGE CASTRO (LAC) ARG 2. NOT RATED 2. VIRGIL HILL USA 2. SILVIO BRANCO (OC) ITA 3. WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO UKR 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 3. GUILLERMO JONES (0C) PAN 3. MANNY SIACA (LAC-INTERIM) P.R. ( Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 4. RAY AUSTIN (LAC) USA 4. STEVE CUNNINGHAM USA (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) 4. GLEN JOHNSON USA ( 5. CALVIN BROCK USA 5. LUIS PINEDA (LAC) PAN 5. PIETRO AURINO ITA l 6. -

ESPN+ to Launch April 12, Bringing Sports Fans More Live Sports, Exclusive Originals and On-Demand Library – All for $4.99 Per Month

ESPN+ to Launch April 12, Bringing Sports Fans More Live Sports, Exclusive Originals and On-Demand Library – All for $4.99 Per Month ESPN+, the upcoming direct-to-consumer subscription streaming service from Disney Direct-to-Consumer and International in partnership with ESPN and featuring ESPN branded content, will launch on April 12 and offer fans a dynamic lineup of live sports, original content and an unmatched library of award- winning on-demand programming – all for a subscription price of $4.99 per month. ESPN+ will be an integrated part of a completely redesigned and reimagined ESPN App that will be the premier all-in-one digital sports platform for fans. ESPN+ will also be available through ESPN.com. The new ESPN App and ESPN+ showcase the culture of breakthrough innovation at ESPN and across The Walt Disney Company. James Pitaro, ESPN President and Co-Chair, Disney Media Networks, said, “ESPN was built on a belief in innovation and the powerful connection between sports and a remarkable array of fans. That same belief is at the heart of ESPN+ and the new ESPN App. With ESPN+, fans have access to thousands more live games, world class original programs and on-demand sports content, all at a great price. They will get all of that as a part of a completely re-imagined, increasingly personalized ESPN App that provides easy, one-stop access to everything ESPN offers.” ESPN+ is the first direct-to-consumer service offering from Disney Direct-to-Consumer and International, the multiplatform media, technology and distribution organization for high- quality content created by Disney’s Media Networks and Studio Entertainment groups. -

A World Title Shot Is on the Line As Robbie Lawler Battles Matt Brown July 26 in San Jose

A WORLD TITLE SHOT IS ON THE LINE AS ROBBIE LAWLER BATTLES MATT BROWN JULY 26 IN SAN JOSE Las Vegas, Nevada – UFC® returns to SAP Center at San Jose with a title elimination match pitting two knockout artists against one another as No. 1-ranked Robbie Lawler will take on No. 5-ranked Matt Brown with the winner earning a shot at champion Johny Hendricks. Additionally, the card will feature several Bay Area-based fighters in Josh Thomson, Noad Lahat and Kyle Kingsbury. Coming off an impressive third-round finish over an always game Jake Ellenberger, Lawler (23-10, 1 NC, fighting out of Coconut Creek, Fla.) will take on the surging Brown (21-11, fighting out of Columbus, Ohio) in hopes of securing a second crack at UFC gold. Brown, who has put together one of the most impressive runs in mixed martial arts today, currently rides a seven-fight win streak, and will be looking to lock down a title shot he feels is long overdue. On July 26 at SAP Center, two of the best welterweights in the world will put it all on the line in a battle for the top contender position. In addition, light heavyweight (No. 5) Anthony Johnson (17-4, fighting out of Boca Raton, Fla.) is back in the Octagon® after an impressive decision victory over Phil Davis in his return to the UFC earlier this year. The hard-hitting “Rumble” will take on Brazilian star Antonio Rogerio Nogueira (21-5, fighting out of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) as he primes himself for title contention. -

Iron Boy Promotions and Top Rank Boxing Close Out

BOXING LEGEND AND UNDISPUTED HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMPION KLITSCHKO TO TAKE ON UNDEFEATED JENNINGS LIVE AND EXCLUSIVE ON BOXNATION ON APRIL 25TH LONDON (March 27) – BoxNation are delighted to announce they will be screening undisputed heavyweight world champion Wladimir Klitschko’s April 25th fight with leading contender Bryant Jennings live and exclusive. The Ukrainian superstar has enjoyed a 10-year title reign at the top of boxing’s glamour division but will now put his WBA, WBO, IBF and IBO belts on the line against the undefeated Jennings at the legendary Madison Square Garden in New York. Klitschko will return to fight on US soil for the first time since February 2008, with the bout set to have high British interest with Manchester heavyweight Tyson Fury mandated to fight the winner later this year. Overcoming Jennings will be no easy task for 39-year-old Klitschko, with the Philadelphian, who has a three-inch reach advantage, hoping to become the first unified American heavyweight champion in more than 13 years. After building up an unbeaten record of 19 straight wins, 10 coming by way of knockout, Jennings is confident that he can finally become the man to dethrone Klitschko, who has won 63 fights, 53 by knockout, with only 3 losses – the last coming over a decade ago. “I do have great respect for Bryant Jennings and his achievements. He has good movement in the ring and good technique. I know this will be a tough challenge,” said Klitschko. “I am extremely happy to fight in New York City again. I had my first unification fight there and a lot of great heavyweight matches have taken place at Madison Square Garden. -

Enjoy Dinner at Iccara Italian Bistro & Seafood in Cape

ENJOY DINNER AT ICCARA ITALIAN BISTRO COFFEE, BAGELS, SANDWICHES & MORE AT & SEAFOOD IN CAPE MAY • SEE PAGE 18 THE WILD FOX CAFE • SEE PAGE 24 PAGE 2 PAGE 3 PAGE 4 TV CHALLENGE SPORTS STUMPERS HALLENGE STUMPERS HALLENGE STUMPERS TV C SPORTSTrash talk TV C SPORTS By George Dickie 7) Who once hit a free throw with Trash histalk eyes closed and announced to the opposing team’s rookie Trash talk ByQuestions: George Dickie 7) Who once hit a free throw with By George Dickie 7) Who once hit a free throw with 1) In 2009, New York Jets free hiscenter, eyes closed“Welcome and toannounced the NBA”? his eyes closed and announced to8) the What opposing quarterback team’s “guaranrookie - Questions:safety Kerry Rhodes was quoted Questions: to the opposing team’s rookie 1)as In saying 2009, heNew wanted York Jetsto “embar free - center,teed” victory“Welcome for histo the team NBA”? in Su- center, “Welcome to the NBA”? 8) What quarterback “guaran- 1) In 2009, New York Jets free safetyrass” Kerryan upcoming Rhodes AFCwas Eastquoted op - per Bowl III? 8) What quarterback “guaran- teed” victory for his team in Su- safety Kerry Rhodes was quoted asponent. saying Name he wanted the opponent. to “embar- 9) What heavyweight champ teed” victory for his team in Su- per Bowl III? as saying he wanted to “embar- rass”2) What an upcoming heavyweight AFC champion East op- once said his opponent was “so per Bowl III? ponent. Name the opponent. 9) What heavyweight champ rass” an upcoming AFC East op- ugly that he should donate his 9) What heavyweight champ 2)once What said heavyweight he wanted champion to eat the once said his opponent was “so ponent.