Vi Post Partition Transport and Communication Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bihar and West Bengal (Transfer of Territories) Act, 1956 ______Arrangement of Sections ______Chapter I Preliminary Sections 1

THE BIHAR AND WEST BENGAL (TRANSFER OF TERRITORIES) ACT, 1956 _______ ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS ________ CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title. 2. Definitions. PART II TRANSFER OF TERRITORIES 3. Transfer of territories from Bihar to West Bengal. 4. Amendment of First Schedule to the Constitution. PART III REPRESENTATION IN THE LEGISLATURES Council of States 5. Amendment of Fourth Schedule to the Constitution. 6. Bye-elections to fill vacancies in the Council of States. 7. Term of office of members of the Council of States. House of the people 8. Provision as to existing House of the People. Legislative Assemblies 9. Allocation of certain sitting members of the Bihar Legislative Assembly. 10. Duration of Legislative Assemblies of Bihar and West Bengal. Legislative Councils 11. Bihar Legislative Council. 12. West Bengal Legislative Council. Delimitation of Constituencies 13. Allocation of seats in the House of the People and assignment of seats to State Legislative Assemblies. 14. Modification of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Orders. 15. Determination of population of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. 16. Delimitation of constituencies. PART IV HIGH COURTS 17. Extension of jurisdiction of, and transfer of proceedings to, Calcutta High Court. 18. Right to appear in any proceedings transferred to Calcutta High Court. 19. Interpretation. 1 PART V AUTHORISATION OF EXPENDITURE SECTIONS 20. Appropriation of moneys for expenditure in transferred Appropriation Acts. 21. Distribution of revenues. PART VI APPORTIONMENT OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES 22. Land and goods. 23. Treasury and bank balances. 24. Arrears of taxes. 25. Right to recover loans and advances. 26. Credits in certain funds. -

Introduction

CHAPTER - I INTRODUCTION West Bengal is now the third most populous state in India, with a population density of a little more than 900 persons per square km. The state continues to attract a large number of migrants from neighbouring states as well as neighbouring countries. Its topography is dominated by the alluvial plains of the Ganga and its tributaries, except for the hilly terrain of North Bengal, extending into the Himalayan foothills. During the last few decades West Bengal has recorded high rates of agricultural growth. It also has a strong industrial base which needs to be further strengthened and diversified. Before we begin our detailed review of the situation of women in West Bengal, it would be useful to gain a broader perspective by looking at certain important socio-economic indicators which have been compiled in Tables S 1, S 2 and S 3. The first two Tables depict the position of West Bengal in an all-India context while the third presents a birds eye view of regional variations within the state of West Bengal, based on available district level information. West Bengals population growth rate during 1991-2001 has been 1.8 per cent per year, lower than the all-India annual growth of rate of 2.1 per cent. Similarly, levels of infant mortality, maternal mortality and total fertility are also well below the respective national averages. However, though the states female literacy rate at 60 per cent is appreciably higher than the all-India proportion of 54 per cent, its worker-population ratio for women at 18 per cent is substantially lower than the all-India figure of about 26 per cent. -

Chapter2 the Region and the Tribal People

CHAPTER2 THE REGION AND THE TRIBAL PEOPLE THE REGION / . West Bengal .......... West Bengal is a land of natural beauty, exquisite lyrical poetry and enthusiastic people. Situated in the east of India, West Bengal is stretches from the Himalayas in the north to the Bay of Bengal in the South. This state shares international boundaries with Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal. Hence it is a strategically important place. The State is interlocked by the other states like Sikkim, Assam, Orissa and Bihar. The river Hooghly and its tributaries, Mayurakshi, Damodar, Kangsabati and the Rupnarayan, enrich the soils of Bengal. The northern districts of West Bengal like Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri and Coach Bihar (in the Himalayas rariges) are watered by the rivers Tista, Torsa, Jaldhaka and Ranjit. From the northern places (feet of Himalayas) to the tropical forests of Sunderbans, West Bengal is a land of incessant beauty. The total area of West Bengal is 88, 752 square kilometers. There are 37,910 inhabited villages and 38,024 towns in West Bengal as per 1991 census. Census population of West Bengal is 8,02,21,171 (2001 ). The density of population as per 2001 census is 904. Sex ratio of West Bengal (females per thousand males) as per 2001 census is 934 and the literacy rate as per 2001 census is 69.22 per cent. The Scheduled Tribe population in West Bengal as per 1991 census is 38,08,760. The percentage of Scheduled Tribe population to total population as per 1991 census is 5.59. The District of Dakshin Dinajpur The district of Dakshin Dinajpur is situated in the northern part of the State of West Bengal. -

Sculptures of the Goddesses Manasā Discovered from Dakshin Dinajpur District of West Bengal: an Iconographic Study

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 10 Issue 4 Ser. I || April 2021 || PP 30-35 Sculptures of the Goddesses Manasā Discovered from Dakshin Dinajpur District of West Bengal: An Iconographic Study Dr Rajeswar Roy Assistant Professor of History M.U.C. Women’s College (Affiliated to The University of Burdwan) Rajbati, Purba-Bardhaman-713104 West Bengal, India ABSTRACT: The images of various sculptures of the goddess Manasā as soumya aspects of the mother goddess have been unearthed from various parts of Dakshin Dinajpur District of West Bengal during the early medieval period. Different types of sculptural forms of the goddess Manasā are seen sitting postures have been discovered from Dakshin Dinajpur District during the period of our study. The sculptors or the artists of Bengal skillfully sculpted to represent the images of the goddess Manasā as snake goddess, sometimes as Viṣahari’, sometimes as ‘Jagatgaurī’, sometimes as ‘Nāgeśvarī,’ or sometimes as ‘Siddhayoginī’. These artistic activities are considered as valuable resources in Bengal as well as in the entire world. KEYWORDS: Folk deity, Manasā, Sculptures, Snake goddess, Snake-hooded --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 20-03-2021 Date of Acceptance: 04-04-2021 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION Dakshin Dinajpur or South Dinajpur is a district in the state of West Bengal, India. It was created on 1st April 1992 by the division of the erstwhile West Dinajpur District and finally, the district was bifurcated into Uttar Dinajpur and Dakshin Dinajpur. Dakshin Dinajpur came into existence after the division of old West Dinajpur into North Dinajpur and South Dinajpur on 1st April, 1992. -

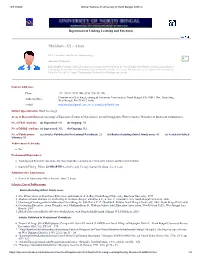

Mahbub - Ul - Alam

12/31/2020 Official Website of University of North Bengal (N.B.U.) ENLIGHTENMENT TO ERFECTION Department of Lifelong Learning and Extension Mahbub - Ul - Alam M.A. (Sociology and Social Anthropology) Associate Professor Life Member- Indian Adult Education Association and President of its West Bengal State Branch; Indian Association of Continuing Association; PaschimBangaVigyan Mancha, Founder Secretary, Balason Society for Improved Environment; Founder General Secretary, Chaitanyapur Shishutirtha Shikshaprasar Samiti Contact Addresses: Phone +91- 9434143574 (M), 0353-2581532 (R) Department of Lifelong Learning & Extension, University of North Bengal, P.O.-NBU, Dist. Darjeeling, Address(office) West Bengal, Pin-734013, India. e-Mail [email protected] , [email protected] Subject Specialization: Rural Sociology Areas of Research Interest: Sociology of Education (Formal & Non-formal), Social Demography, Women Studies, Minorities & Backward Communities. No. of Ph.D. students: (a) Supervised: Nil (b) Ongoing: Nil No. of M.Phil. students: (a) Supervised: NA (b) Ongoing: NA. No. of Publications: (a) Articles Published in Professional Periodicals: 25 (b) Books (Including Edited Jointly ones): 05 (c) Articles in Edited Volumes: 08 Achievement & Awards: No Professional Experiences: Teaching and Research experience for more than three decades as a University teacher and Research Scholar. Journals Editing: Editor, SAMBARTIKA, a half yearly Literary Journal for about eleven years. Administrative Experiences: Served as University Officer for more than 22 years. Selective List of Publications: Books (Including Edited Jointly ones): 1. New Thrust Areas of Population Education, with Sinha A. & A. Roy, North Bengal University, Burdwan University, 1997. 2. Medicinal Plants Suitable for Cultivating in Northern Bengal, with Das A.P., A. Sen, C. -

Mapping the Districts of West Bengal Using Geospatial Technology

Indian Journal of Spatial Science Spring Issue, 10 (1) 2018 pp. 112 - 121 Indian Journal of Spatial Science Peer Reviewed and UGC Approved (Sl No. 7617) EISSN: 2249 - 4316 homepage: www.indiansss.org ISSN: 2249 - 3921 Mapping the Districts of West Bengal using Geospatial Technology Dr Ashis Sarkar Professor of Geography (Retired), West Bengal Senior Education Service: Presidency College / University and Chandernagore College Partha Nandi GIS Executive, Ceinsys Tech Limited, Nagpur, Maharashtra Arpan Giri GIS Business Developer/Analyst, MMS.IND (LSI Micro-Marketing Service India Pvt. Ltd.), Mumbai Article Info Abstract _____________ ___________________________________________________________ Article History The Partition of Bengal in 1947 divided the British Indian province of Bengal based on the Radcliffe Line between India and Pakistan.The Hindu dominated West Bengal became a province of India, and Received on: theMuslim dominated East Bengal (now Bangladesh) became a province of Pakistan. The Indian state 31 July 2018 of West Bengal borders with Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and the Indian states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Accepted inRevised Form on : Odissa, Assam and Sikkim. The Himalayas lie in the north and the Bay of Bengal in the south. In 15 February, 2019 betweenflows the Ganga eastwards and its main distributary, the Bhagirathi flows south to reach the AvailableOnline on and from : Bay of Bengal. The Siliguri Corridor(or the Chicken Neck of West Bengal) that connects North-East 21 March, 2019 India withthe rest of the country lies in the North Bengal region of the state. Geographically, the state of __________________ West Bengal is divided into a variety of regions, viz. Darjeeling Himalayas, , Terai Dooars, North Key Words Bengal plains, Rarh, Western plateau and high lands, coastal plains, Sunderbans and the Ganga Delta. -

TB in Tribal Community in Uttar Dinajpur (West Bengal) in 2011

TB in Tribal Community in Uttar Dinajpur (West Bengal) in 2011 -Prabir Chatterjee , Prakash Baag, Anwar Hossain 1 Dear Editor, We write to report findings from the TB data in the fourth quarter of 2011 in West Bengal. When doing an analysis by community, the TB Officer found that a very large percentage of TB patients in our district were from tribal communities. There are 9 development blocks in Uttar Dinajpur. There are 6 TU. Cases of TB were highest in Raiganj and Kaliaganj Tuberculosis Units. Karandighi and Dalua blocks. Cases There were 308 new smear positive patients detected in the fourth quarter of 2011. 70 patients were from tribal communities. Tribal patients were 3 of 34 TB in Karandighi and 9 of 36 in Itahar, 11 of 68 in Kaliaganj and 31 of 71 in Raiganj. 11 of 62 patients in Islampur were tribal. In Lodhan 5 patients were tribal out of 37. 1Respectively Medical Officer, Kaliaganj Municipality, Uttar Dinajpur, West Bengal; District Tuberculosis Officer, Uttar Dinajpur; and former District Tuberculosis Officer, Uttar Dinajpur. Email contact: [email protected] ST Patients out of Total New Smear Positive under RNTCP, Uttar Dinajpur 4th Quarter 2011 Total ST New Patients Sputum out of Positive Total Name of TU BPHC Town Patients NSP Percentage Raiganj DTC TU Raiganj Raiganj 71 31 43.66 Islampur TU Ramganj, Dalua Islampur 62 11 17.74 Kaliyaganj, Kaliyaganj TU Hemtabad Kaliyaganj 68 11 16.18 Itahar TU Itahar 36 9 25.00 Karandighi TU Karandighi Dalkhola 34 3 8.82 Lodhan TU Lodhan, Chakulia 37 5 13.51 Total Uttar Dinajpur 308 70 22.73 Tribals consist of only 7% of the population of Dalua / Chopra, 7 % in Karandighi, 7.9% in Itahar, 5.8% of Raiganj, 4.6% of Kaliaganj, 6.2 % of Chakulia and 5.4 % of the district. -

Districtv Ijlans of West Bengal 1956-61

Government of i* W est Bengal Districtv IJlans of West Bengal 1956-61 330.»S4WB W516D P.C.SL CONTENTS Introductorv note District Plaa— Burdwan 1 Birbhuia 14 Bankura 26 Midnapore 38 Hooghly ., 53 Howrah .. 65 24-Parganae 76 Calcutta .. 90 Nadia .. 95 Murshidabad 107 Malda 121 West Dinajpur 134 Jalpaiguri ,. 146 Darjeeling 158 Cooch Behar 169 Purulia .. 180 Appendix'— Schemes not classified imder district plan.. 184 U) DISTRICT PLANS INTRODUCTORY NOTE According to the direction of the Planning Commission, a State Plan has to resented in two different ways, namely, according to different sectors of develop- t represented in it and according to regions or districts. We have already ared and published our Plan according to sectors of development and now jreak up the Plan district-wise. This is necessary in order to educate public ion, encourage local initiative and obtain public Co-operation in the execution Ihe Plan. The National Plan and the State Plan are being prepared on annual basis within Framework of the Five-Year Plan in order to make necessary modifications and stments in the course of execution. Consequently the appropriate period District Plans would also be a year. We accordingly began preparing our rict Plans with particular reference to the first year against the background le Five Year Plan. Originally the intention was that such District Plans would repared every year. But from our experience in the works so far, it seems that aration of annual District Plans every year may not be possible under the ?nt circumstances. We have, therefore given in the following pages the dis- -wise break up of the Plan as a whole as far as available. -

A Study on Status of Socio-Economic Conditions of Dakshin Dinajpur District : a Geographical Analysis

A STUDY ON STATUS OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC CONDITIONS OF DAKSHIN DINAJPUR DISTRICT : A GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PH. D) IN GEOGRAPHY AND APPLIED GEOGRAPHY SUBMITTED BY RANJAN SARKAR UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. RANJAN ROY PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND APPLIED GEOGRAPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL JANUARY, 2019 ii iii iv Dedication This Thesis is dedicated to: God, my Creator and my Master, My whole family especially great grant parents, parents, wife, elder sister and yes my beloved kids who never stop giving support in countless ways, My all respected teachers who taught me the purpose of life and to be what I am today, My all Friends, Colleagues and Students who encouraged and supported me, All the people in my life who touched my heart, All beloved People of Dakshin Dinajpur District. v Preface At the time of having Independence, India inherited from the British an economy severely afflicted by regional disparities. The British Ruler looked at the problem of regional imbalances in the country as a natural manifestation of varying resource endowments of different regions and their geographical distribution. However, after independence policy makers and social scientists viewed the problem of regional imbalances differently. No country can be regarded to have a well-balanced economic growth if there are large disparities between the levels of development and standard of living between people of different regions of the country itself and different classes of people in the same region. In our country the problems of Socio-Economic imbalances are growing rapidly. -

Utilization of Irrigation on Agriculture in Uttar Dinajpur District, West Bengal, India

Innovations Number 61 2020 April www.journal-innovations.com Utilization of Irrigation on agriculture in Uttar Dinajpur District, West Bengal, India Suchandra Neogi Research Scholar Department of Geography The University of Burdwan West Bengal, India Abstract Irrigation is practised in those areas where rainfall is seasonal and the amount is not satisfactory for crop production. The monsoonal land having seasonal rainfall, require irrigation either from canal, tank or well so as to ensure agricultural production. In India rainfall is seasonal and the distribution of rainfall is uneven. India has the largest acreage of land under irrigation. In the high irrigated area the cropping intensity is found high and in the low irrigated area cropping intensity is found low. This article focussed on the present status of irrigation and cropping pattern on block basis in the Uttar Dinajpur district, in West Bengal, India. After applying different methods and technique (Pearson’s product moment correlation co-efficient, Regression line etc.). It has been concluded that the districts has a positive relation between two variables. Though the ground water utilisation is the main source of irrigation but other sources are also used to increase the cropping intensity in the region. Some blocks gets high irrigation facilities but the facilities is not well enough. Key words: 1.Irrigation, 2.Irrigation by Teesta Canal, 3.Cropping Intensity , 4.Suggested remedial measures. Introduction: Water potential in India is vast. This can be tapped and usefully employed for irrigation. Irrigation is the artificial application of water to the land or soil. It is used to assist during periods of inadequate rainfall. -

Brief Industrial Profile of UTTAR DINAJPUR DISTRICT WEST BENGAL

lR;eso t;rs Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of UTTAR DINAJPUR DISTRICT WEST BENGAL Carried out by MSME-Development Institute K olkata (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone: (033)2577-0595/7/8 Fax: (033)2577-5531 E-mail: [email protected] Web-www.msmedikolkata.gov.in Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 3 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 3 1.4 Forest 3 1.5 Administrative set up 4 2. District at a glance 4 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in Uttar Dinajpur 5 3. Industrial Scenario Of Uttar Dinajpur district 5 3.1 Industry at a Glance 5 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 6 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan 6 Units In The District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 7 3.5 Major Exportable Item 7 3.6 Growth Trend 7 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 7 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 7 3.8.1 List of the units in Uttar Dinajpur & near by Area 7 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 7 3.9 Service Enterprises 8 3.9.1 Potentials areas for service industry 8 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 8 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 11 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 11 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 11 4.1.2 Service Sector 11 4.2 Details of Identified cluster 11 5. -

The Dismal Picture of Lentic Water Bodies and Over Exploitation of Ground Water Storage in Raiganj Block, of North Dinajpur District, W.B., India

International Journal of Trend in Research and Development, Volume 7(4), ISSN: 2394-9333 www.ijtrd.com The Dismal Picture of Lentic Water Bodies and Over Exploitation of Ground Water Storage in Raiganj Block, of North Dinajpur District, W.B., India 1Abhishek Sinha and 2Amal Bhattacharya, 1Research Scholar, 2Associate Professor, 1,2Department of Zoology, Raiganj University, West Bengal, India Abstract: India is experiencing a gradual acute shortage of than 50% of total precipitation flows to the rivers and it is water resources due to global warming as well as by excessive estimated to be 1869 billion cubic meters. However, only 690 extraction of groundwater and by much use of the other lentic billion cubic meter surface water resources can actually be water bodies due to excessive population growth. Raiganj utilised (Central Water Commission 2015). block of North Dinajpur District of W.B., India is also facing A. Study site the same problem. Almost 30% to 40% of water bodies have disappeared permanently from the map of Raiganj block during The entire study area was confined within the jurisdiction of the last three decades. The dismal picture of water bodies Raiganj (25.62oN and 88.12oE) block and this survey work was shows that less than 2.25% area is covered under lentic water carried out from March, 2019 to the end of February 2020. bodies in Raiganj block. The condition becomes severe in the Raiganj block is located in the North Dinajpur District of West hot dry months, when, altogether only 17% rainfall occurs, but, Bengal, India (Fig.1a and 1b), the administrative headquarters the average temperature rises up to 36.4o C.