Leopard C1 Tank for During Exercise Jointex 15, As the Canadian Army Part of NATO’S Exercise Trident by Frank Maas Juncture, 31 October 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Firing US 120Mm Tank Ammunition in the Leopard 2 Main Battle Tank

An advanced weapon and space systems company Firing US 120mm Tank Ammunition in the Leopard 2 Main Battle Tank NDIA Guns and Missiles Conference Harlan Huls 22 April 2008 1_T105713Cauthor.ppt 04/03/20001 1 Agenda An advanced weapon and space systems company 1. Overview of tanks and ammunition • Interoperability of the weapon and ammunition 2. Objectives of the test conducted in Denmark 3. Results of the firings in Leopard 2 with L44 and L55 weapon system 4. Conclusions 2 Description of US Tank Ammunition An advanced weapon and space systems company US 120mm Tank Ammunition Types M1028 KEWA2™ M829A3 M830A1 M1002 M831A1 M830 M908 M865 Canister APFSDS-T APFSDS-T HEAT-MP-T TPMP-T TP-T HEAT-MP-T HE-OR-T TPCSDS-T Several US ammunition types with interoperability maintained through International JCB by controlling interface features (ICD) 3 Abrams and Leopard 2 MBT With 120mm Smoothbore Cannon An advanced weapon and space systems company Leopard 2 Tanks Abrams Tanks Leo2A6 L55 Weapon (Dutch) M1A1 Abrams Leo2A5 (M256 ~ L44 Weapon) L44 Weapon (Danish) Leo2A4 M1A2 Abrams L44 Weapon (M256 ~ L44 Weapon) Several MBT configurations with 120mm weapon. Interoperability is maintained through international JCB by controlling interface features (ICD) 4 120mm Smoothbore Compatible Platforms An advanced weapon and space systems company Platform Picture Type and Country Caliber Basic Tactical Training Comments Load Rounds Rounds M1A1 Abrams 44 40 M829A3 M865 Training and USA, Australia, rounds M829A2 M831A1 Tactical designed M829A1 for 120mm Kuwait, Egypt -

Commonality in Military Equipment

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Arroyo Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Commonality in Military Equipment A Framework to Improve Acquisition Decisions Thomas Held, Bruce Newsome, Matthew W. -

Characteristics of Torsion Bar Suspension Elasticity in Mbts and the Assessment of Realized Solutions

Scientific-Technical Review,vol.LIII,no.2,2003 67 UDC: 623.438.3(047)=20 COSATI: 19-03, 20-11 Characteristics of torsion bar suspension elasticity in MBTs and the assessment of realized solutions Rade Stevanović, BSc (Eng)1) On the basis of available data and known equations, basic parameters of suspension systems in a number of main bat- tle tanks with torsion bar suspension are determined. On the basis of the conclusions obtained from the presented graphs and the table, the characteristics of torsion bar suspension elasticity in some main types of tanks are assessed. Key words: main battle tank, suspension, torsion bar, elasticity, work load capacity. Principal symbols Union), the US and Germany, in one type of French and one Japanese main battle tank, and in some British tanks for a – swing arm length export as well. All other producers from other countries, c – torsion bar spring rate whose main battle tanks had the torsion bar suspension, Crs – reduced torsion bar spring rate in the static wheel mainly used the licence or the experience of the previously position, suspension characteristic derivate in the mentioned countries. static wheel position The characteristics of torsion bar suspension systems in d – torsion bar diameter main battle tanks in serial production until the 60s for the fd – positive vertical spring travel, static-to-bump use in NATO forces (M-47 and M-48) and the Warsaw movement Treaty countries (T-54 and T-55), were of nearly the same fs, fm – rebound and total vertical spring travel (low) level, but still higher than the British tank Centurion Fs – vertical wheel load on the road wheel in the static characteristics, with BOGEY suspension, which was also wheel position in serial production at that time. -

York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) Finding

York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) Finding Aid - Richard Jarrell fonds (F0721) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.5.3 Printed: December 16, 2019 Language of description: English York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) 305 Scott Library, 4700 Keele Street, York University Toronto Ontario Canada M3J 1P3 Telephone: 416-736-5442 Fax: 416-650-8039 Email: [email protected] http://www.library.yorku.ca/ccm/ArchivesSpecialCollections/index.htm https://atom.library.yorku.ca//index.php/richard-jarrell-fonds Richard Jarrell fonds Table of contents Summary information .................................................................................................................................... 10 Administrative history / Biographical sketch ................................................................................................ 10 Scope and content ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Notes .............................................................................................................................................................. 11 Access points ................................................................................................................................................. 12 Collection holdings ....................................................................................................................................... -

The Order of Military Merit to Corporal R

Chapter Three The Order Comes to Life: Appointments, Refinements and Change His Excellency has asked me to write to inform you that, with the approval of The Queen, Sovereign of the Order, he has appointed you a Member. Esmond Butler, Secretary General of the Order of Military Merit to Corporal R. L. Mailloux, I 3 December 1972 nlike the Order of Canada, which underwent a significant structural change five years after being established, the changes made to the Order of Military U Merit since 1972 have been largely administrative. Following the Order of Canada structure and general ethos has served the Order of Military Merit well. Other developments, such as the change in insignia worn on undress ribbons, the adoption of a motto for the Order and the creation of the Order of Military Merit paperweight, are examined in Chapter Four. With the ink on the Letters Patent and Constitution of the Order dry, The Queen and Prime Minister having signed in the appropriate places, and the Great Seal affixed thereunto, the Order had come into being, but not to life. In the beginning, the Order consisted of the Sovereign and two members: the Governor General as Chancellor and a Commander of the Order, and the Chief of the Defence Staff as Principal Commander and a similarly newly minted Commander of the Order. The first act of Governor General Roland Michener as Chancellor of the Order was to appoint his Secretary, Esmond Butler, to serve "as a member of the Advisory Committee of the Order." 127 Butler would continue to play a significant role in the early development of the Order, along with future Chief of the Defence Staff General Jacques A. -

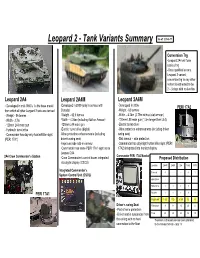

Leopard 2 - Tank Variants Summary As Of: 21 Feb 11

Leopard 2 - Tank Variants Summary As of: 21 Feb 11 Conversion Trg -Leopard 2A4 will form basis of trg -Once qualified on any Leopard 2 variant, conversion trg to any other variant is estimated to be 2 – 3 days with no live fire Leopard 2A4 Leopard 2A4M Leopard 2A6M - Developed in mid-1980’s. Is the base model -Developed in 2009 (only in service with -Developed in 2006 PERI 17A2 from which all other Leopard 2 tank are derived Canada) -Weight - 63 tonnes - Weight - 56 tonnes -Weight – 62.5 tonnes -Width – 4.24m (3.75m without slat armour) - Width - 3.7m -Width – 4.05m (including Add-on Armour) -120mm L55 main gun (1.3m longer than L44) - 120mm L44 main gun -120mm L44 main gun -Electric turret drive - Hydraulic turret drive -Electric turret drive (digital) -Mine protection enhancements (including driver - Commander has day-only hunter/Killer sight -Mine protection enhancements (including swing seat) (PERI 17A1) driver’s swing seat) -Slat armour – side protection -Improved side add-on-armour -Commander has day/night hunter killer sight (PERI -Commander has same PERI 17A1 sight as on 17A2) integrated into monitor display Leopard 2A4 2A4 Crew Commander’s Station -Crew Commander’s control boxes integrated Commander PERI 17A2 Monitor Proposed Distribution into digital display (CSCU) Location 2A4M 2A6M 2A4 Total ARV Integrated Commander’s Fenced 4 - - 4 1 System Control Unit (CSCU) Ops Stock - - - - - Reference 1 1 1 3 - PERI 17A1 Borden 1 1 1 3 1 Gagetown* 5 (2) 7 (2) 20 (9) 32 4 Driver’s swing Seat Edmonton 9 11 20 40 4 -Part of mine protection -

1866 (C) Circa 1510 (A) 1863

BONUS : Paintings together with their year of completion. (A) 1863 (B) 1866 (C) circa 1510 Vancouver Estival Trivia Open, 2012, FARSIDE team BONUS : Federal cabinet ministers, 1940 to 1990 (A) (B) (C) (D) Norman Rogers James Ralston Ernest Lapointe Joseph-Enoil Michaud James Ralston Mackenzie King James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent 1940s Andrew McNaughton 1940s Douglas Abbott Louis St. Laurent James Ilsley Louis St. Laurent Brooke Claxton Douglas Abbott Lester Pearson Stuart Garson 1950s 1950s Ralph Campney Walter Harris John Diefenbaker George Pearkes Sidney Smith Davie Fulton Donald Fleming Douglas Harkness Howard Green Donald Fleming George Nowlan Gordon Churchill Lionel Chevrier Guy Favreau Walter Gordon 1960s Paul Hellyer 1960s Paul Martin Lucien Cardin Mitchell Sharp Pierre Trudeau Leo Cadieux John Turner Edgar Benson Donald Macdonald Mitchell Sharp Edgar Benson Otto Lang John Turner James Richardson 1970s Allan MacEachen 1970s Ron Basford Donald Macdonald Don Jamieson Barney Danson Otto Lang Jean Chretien Allan McKinnon Flora MacDonald JacquesMarc Lalonde Flynn John Crosbie Gilles Lamontagne Mark MacGuigan Jean Chretien Allan MacEachen JeanJacques Blais Allan MacEachen Mark MacGuigan Marc Lalonde Robert Coates Jean Chretien Donald Johnston 1980s Erik Nielsen John Crosbie 1980s Perrin Beatty Joe Clark Ray Hnatyshyn Michael Wilson Bill McKnight Doug Lewis BONUS : Name these plays by Oscar Wilde, for 10 points each. You have 30 seconds. (A) THE PAGE OF HERODIAS: Look at the moon! How strange the moon seems! She is like a woman rising from a tomb. She is like a dead woman. You would fancy she was looking for dead things. THE YOUNG SYRIAN: She has a strange look. -

Crescent Moon Rising? Turkish Defence Industrial Capability Analysed

Volume 4 Number 2 April/May 2013 Crescent moon rising? Turkish defence industrial capability analysed SETTING TOOLS OF FIT FOR THE SCENE THE TRADE PURPOSE Urban combat training Squad support weapons Body armour technology www.landwarfareintl.com LWI_AprMay13_Cover.indd 1 26/04/2013 12:27:41 Wescam-Land Warfare Int-ad-April 2013_Layout 1 13-03-07 2:49 PM Page 1 IDENTIFY AND DOMINATE L-3’s MXTM- RSTA: A Highly Modular Reconnaissance, Surveillance and Target Acquisition Sighting System • Configurable as a Recce or independent vehicle sighting system • Incorporate electro-optical/infrared imaging and laser payloads that match your budget and mission portfolio • 4-axis stabilization allows for superior on-the-move imaging capability • Unrivaled ruggedization enables continuous performance under the harshest climates and terrain conditions MX-RSTA To learn more, visit www.wescam.com. WESCAM L-3com.com LWI_AprMay13_IFC.indd 2 26/04/2013 12:29:01 CONTENTS Front cover: The 8x8 Pars is one of a growing range of armoured vehicles developed in Turkey. (Image: FNSS/Lorna Francis) Editor Darren Lake. [email protected] Deputy Editor Tim Fish. [email protected] North America Editor Scott R Gourley. [email protected] Tel: +1 (707) 822 7204 European Editor Ian Kemp. [email protected] 3 EDITORIAL COMMENT Staff Reporters Beth Stevenson, Jonathan Tringham Export drive Defence Analyst Joyce de Thouars 4 NEWS Contributors • Draft RfP outlines US Army AMPV requirements Claire Apthorp, Gordon Arthur, Mike Bryant, Peter Donaldson, • Navistar delivers first Afghan armoured cabs Jim Dorschner, Christopher F Foss, • Canada solicits bids for integrated soldier system Helmoed Römer Heitman, Rod Rayward • KMW seals Qatar tank and artillery deal Production Manager • Dutch Cheetah air defence guns sold to Jordan David Hurst Sub-editor Adam Wakeling 7 HOME GROWN Commercial Manager Over the past three decades, Turkey has gradually Jackie Hall. -

The Canadian Forces' Decorations

The Canadian Forces’ Decoration Christopher McCreery Foreword by His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh CONTACT US To obtain more information contact the: Directorate of Honours and Recognition National Defence Headquarters 101 Colonel By Drive Ottawa, ON K1A 0K2 http://www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhr-ddhr/ 1-877-741-8332 DGM-10-04-00007 The Canadian Forces’ Decoration Christopher McCreery Foreword by His Royal Highness The DukeThe Canadian of Edinburgh Forces’ Decoration | i Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II wearing her uniform as Colonel- in-Chief of the Scots Guards during a ceremony of Trooping the Colour in London, United Kingdom. The Canadian Forces’ Decoration she received as a Princess in 1951 can be seen at the end of her group of medals The Canadian Forces’ Decoration Dedication ...............................................................................................iv Frontispiece ................................................................................................v Foreword H.R.H. The Duke of Edinburgh, KG, KT, PC, OM, GBE, AC, QSO, GCL, CD, ADC ..............................vii Preface General Walter Natynczyk, CMM, MSC, CD .........................ix Author’s Note ................................................................................................x Acknowledgements ...............................................................................................xi Introduction .............................................................................................xiii Chapter One Early Long Service -

Fall 2 0 Fall

LIVING THE FALL 2017 1 WWW.LCC.CA IN FALL 2018, LCC WILL HOST THE INTERNATIONAL ROUND SQUARE CONFERENCE Over 450 student and teacher delegates from all over the world will join us. LION HEADMASTER CHRISTOPHER SHANNON (PRE-U ’76) LION EDITOR DAWN LEVY COPY EDITORS ASHWIN KAUSHAL DANA KOBERNICK JANE MARTIN ARCHIVES, RESEARCH & DATABASE JANE MARTIN LOUISE MILLS 19 38 44 ADRIANNA ZEREBECKY TRANSLATION DOMINIQUE PARÉ CONTRIBUTORS What’s Fall RICHARD ANDREWS 2017 LUCIA HUANG ’17 (PRE-U ’18) DANA KOBERNICK WAYNE LARSEN DAWN LEVY Inside DOUG LEWIN ‘87 KIRK LLANO JANE MARTIN CHRISTOPHER SHANNON Head Lines / ADVENTURE Report to Donors NANCY SMITH À la une 2016 – 2017 02 41 CHRIS VIAU Where on Earth is SHARMAN YARNELL What's the 19 Emma McLaren ’99? Message from the 05 Big IDEALS? 42 Headmaster & PHOTO CREDITS Dogsledding Chairman of the Board & CONTRIBUTORS INTERNATIONALISM 21 Adventure of Governors ABOUTORKNEY.COM CHRISTIAN AUCLAIR LCC’s Admissions LEADERSHIP Dining Hall & Student A. VICTOR BADIAN 07 Alumni Ambassador 44 Life Area: Transformed! SCOTT BROWNLEE Program Round Square DANE CLOUSTON 24 Conferences Annual Giving ANABELA CORDEIRO What Does 48 Wrap-up LCC ARCHIVES 08 Global Citizenship SERVICE STEPHEN LEE Mean to You? Giving by SARAH MAHONEY LCC Trip 52 the Numbers CHRISTINNE MUSCHI DEMOCRACY 27 to India KYLE WILLIAMS Annual Giving MICHAEL ZAVACKY Students Elizabeth Weale ’05: 54 & Capital Campaign 11 Commemorate 28 A Spark of Light Donors MAILING the Holocaust in Tanzania AUTOMATIC MAILING & PRINTING INC. Parent Involvement ENVIRONMENTALISM Athletics Wrap-Up 60 at LCC: A Family Affair DESIGN 2016 – 2017 30 ORIGAMI All Abuzz About Record of Achievement the Bees Class Acts: 13 62 2016 – 2017 THE LION 34 Caitlin Rose ’99 IS PUBLISHED BY Update on LCC’s & Robert de Branching LOWER CANADA COLLEGE 14 Environmental Fourgerolles ’57 68 Out 4090, AVENUE ROYAL Initiatives MONTRÉAL (QUÉBEC) H4A 2M5 J.C. -

The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2020 A Marriage of Intersecting Needs: The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983 Garison Ma [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Military and Veterans Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons, Political History Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Ma, Garison, "A Marriage of Intersecting Needs: The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983" (2020). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 2330. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/2330 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Marriage of Intersecting Needs: The Procurement of the Canadian Patrol Frigates by the Pierre Trudeau Government, 1977-1983 by Garison Ma BA History, Wilfrid Laurier University, 2018 THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of History in partial fulfilment of the requirements for Master of Arts in History Wilfrid Laurier University © Garison Ma 2020 To my parents, Gary and Eppie and my little brother, Edgar. II Abstract In December 1977, the Liberal government of Pierre Elliot Trudeau authorized the Department of National Defence (DND) to begin the acquisition of new warships for the navy. The decision to acquire fully combat capable warships was a shocking decision which marked the conclusion of a remarkable turnaround in Canadian defence policy. -

Cleaning up Cosmos: Satellite Debris, Radioactive Risk, and the Politics of Knowledge in Operation Morning Light

hƩ ps://doi.org/10.22584/nr48.2018.004 Cleaning up Cosmos: Satellite Debris, Radioactive Risk, and the Politics of Knowledge in Operation Morning Light Ellen Power University of Toronto Arn Keeling Memorial University Abstract In the early morning of January 24, 1978, the nuclear-powered Soviet satellite Cosmos 954 crashed on the barrens of the Northwest Territories, Canada. The crash dispersed radioactive debris across the region, including over multiple communities. A close reading of the archival record of the military-led clean up operation that followed, known as Operation Morning Light, shows how the debris recovery effort was shaped by government understandings of the northern environment as mediated through authoritative science and technology. This authority was to be challenged from the very beginning of Operation Morning Light. Constant technological failures under northern environmental conditions only increased the uncertainty already inherent in determining radioactive risk. Communication of this risk to concerned northerners was further complicated by language barriers in the predominantly Indigenous communities affected. For many northern residents, the uncertainties surrounding radiation detection and mistrust of government communication efforts fueled concerns about contamination and the effectiveness of debris recovery. Though an obscure episode for many Canadians today, the Cosmos crash and recovery intersects with important themes in northern history, including the politics of knowledge and authority in the Cold War North. The Northern Review 48 (2018): 81–109 Published by Yukon College, Whitehorse, Canada 81 On January 28, 1978, amateur explorer John Mordhurst was overwintering in a cabin near Warden’s Grove, a small copse of trees on the Th elon River in the Northwest Territories.