Hollywood's New Yorker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8550/list-of-animated-films-and-matched-comparisons-posted-as-supplied-by-author-8550.webp)

List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]

Appendix : List of animated films and matched comparisons [posted as supplied by author] Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date Snow White and the G 1937 Saratoga ‘Passed’ Stella Dallas G Seven Dwarfs Pinocchio G 1940 The Great Dictator G The Grapes of Wrath unrated Bambi G 1942 Mrs. Miniver G Yankee Doodle Dandy G Cinderella G 1950 Sunset Blvd. unrated All About Eve PG Peter Pan G 1953 The Robe unrated From Here to Eternity PG Lady and the Tramp G 1955 Mister Roberts unrated Rebel Without a Cause PG-13 Sleeping Beauty G 1959 Imitation of Life unrated Suddenly Last Summer unrated 101 Dalmatians G 1961 West Side Story unrated King of Kings PG-13 The Jungle Book G 1967 The Graduate G Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner unrated The Little Mermaid G 1989 Driving Miss Daisy PG Parenthood PG-13 Beauty and the Beast G 1991 Fried Green Tomatoes PG-13 Sleeping with the Enemy R Aladdin G 1992 The Bodyguard R A Few Good Men R The Lion King G 1994 Forrest Gump PG-13 Pulp Fiction R Pocahontas G 1995 While You Were PG Bridges of Madison County PG-13 Sleeping The Hunchback of Notre G 1996 Jerry Maguire R A Time to Kill R Dame Hercules G 1997 Titanic PG-13 As Good as it Gets PG-13 Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date A Bug’s Life G 1998 Patch Adams PG-13 The Truman Show PG Mulan G 1998 You’ve Got Mail PG Shakespeare in Love R The Prince of Egypt PG 1998 Stepmom PG-13 City of Angels PG-13 Tarzan G 1999 The Sixth Sense PG-13 The Green Mile R Dinosaur PG 2000 What Lies Beneath PG-13 Erin Brockovich R Monsters, -

Martin Scorsese and American Film Genre by Marc Raymond, B.A

Martin Scorsese and American Film Genre by Marc Raymond, B.A. English, Dalhousie University A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fultillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario March 20,2000 O 2000, Marc Raymond National Ubrary BibIiot~uenationak du Cana a uisitiis and Acquisitions et "IBib iogmphk Senrices services bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thése sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copy~@t in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts kom it Ni la thèse N des extraits substantiels may be printed or ohenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract This study examines the films of American director Martin Scorsese in their generic context. Although most of Scorsese's feature-length films are referred to, three are focused on individually in each of the three main chapters following the Introduction: Mean Streets (1 973), nie King of Cornedy (1983), and GoodFellas (1990). This structure allows for the discussion of three different periods in the Amencan cinema. -

LACMA ANNOUNCES 2013 ART + FILM GALA HONORING DAVID HOCKNEY and MARTIN SCORSESE

^ LACMA ANNOUNCES 2013 ART + FILM GALA HONORING DAVID HOCKNEY and MARTIN SCORSESE THE 3RD annual event, TO BE HELD ON SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 2013 will be co-chaired by Leonardo D¡Caprio and Eva Chow ALSO CELEBRATING COLLABORATION WITH THE FILM FOUNDATION TO PRESERVE FILMS BY AGNèS VARDA presented by Gucci (Los Angeles, June 17, 2013)— The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is pleased to announce the date and honorees of the 2013 Art+Film Gala. On Saturday, November 2, notables from the art, film, fashion, and entertainment industries will unite at LACMA to honor artist David Hockney and filmmaker Martin Scorsese. For its third year, the 2013 Art+Film Gala is co-chaired by LACMA Trustee Eva Chow and actor Leonardo DiCaprio, who continue to champion LACMA’s film initiatives. Also being celebrated is the first collaboration between The Film Foundation, founded by Martin Scorsese, and LACMA and The Annenberg Foundation, to preserve four films by the acclaimed French filmmaker Agnès Varda. Gucci once again shows its invaluable support of the museum as the presenting sponsor of the 2013 Art+Film Gala, with Gucci Creative Director Frida Giannini as Gala Host Committee Chair. “LACMA continues to integrate film into the museum through film-based exhibitions such as the Stanley Kubrick retrospective, Hans Richter: Encounters and an upcoming exhibition on the Mexican cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa,” said Michael Govan, LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director. “The 2013 Art+Film Gala celebrates our growing achievements in combining art and film at LACMA and is in alignment with our plans to initiate a program to acquire and restore films, in the same way as we do with other works in our collection.” Gala Co-Chair Eva Chow added, “The Art+Film Gala, now in its third year, brings renowned figures from the worlds of art, cinema, fashion, and music together to support the museum. -

Film & Literature

Name_____________________ Date__________________ Film & Literature Mr. Corbo Film & Literature “Underneath their surfaces, all movies, even the most blatantly commercial ones, contain layers of complexity and meaning that can be studied, analyzed and appreciated.” --Richard Barsam, Looking at Movies Curriculum Outline Form and Function: To equip students, by raising their awareness of the development and complexities of the cinema, to read and write about films as trained and informed viewers. From this base, students can progress to a deeper understanding of film and the proper in-depth study of cinema. By the end of this course, you will have a deeper sense of the major components of film form and function and also an understanding of the “language” of film. You will write essays which will discuss and analyze several of the films we will study using accurate vocabulary and language relating to cinematic methods and techniques. Just as an author uses literary devices to convey ideas in a story or novel, filmmakers use specific techniques to present their ideas on screen in the world of the film. Tentative Film List: The Godfather (dir: Francis Ford Coppola); Rushmore (dir: Wes Anderson); Do the Right Thing (dir: Spike Lee); The Dark Knight (dir: Christopher Nolan); Psycho (dir: Alfred Hitchcock); The Graduate (dir: Mike Nichols); Office Space (dir: Mike Judge); Donnie Darko (dir: Richard Kelly); The Hurt Locker (dir: Kathryn Bigelow); The Ice Storm (dir: Ang Lee); Bicycle Thives (dir: Vittorio di Sica); On the Waterfront (dir: Elia Kazan); Traffic (dir: Steven Soderbergh); Batman (dir: Tim Burton); GoodFellas (dir: Martin Scorsese); Mean Girls (dir: Mark Waters); Pulp Fiction (dir: Quentin Tarantino); The Silence of the Lambs (dir: Jonathan Demme); The Third Man (dir: Carol Reed); The Lord of the Rings trilogy (dir: Peter Jackson); The Wizard of Oz (dir: Victor Fleming); Edward Scissorhands (dir: Tim Burton); Raiders of the Lost Ark (dir: Steven Spielberg); Star Wars trilogy (dirs: George Lucas, et. -

AM Mike Nichols Production Bios FINAL

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET, 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #AmericanMasters Mike Nichols: American Masters Premieres nationwide Friday, January 29 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) Production Biographies Elaine May Director Elaine May began in Second City where she formed a successful comedy team with Mike Nichols. She earned a Drama Desk Award for her play Adaptation ; wrote, directed and performed in A New Leaf ; directed The Heartbreak Kid (the original); wrote and directed Mikey & Nicky and Ishtar ; received an Oscar nomination for writing Heaven Can Wait ; reunited with Nichols to write The Birdcage and Primary Colors (a BAFTA-winner); and worked with producer Julian Schlossberg on six New York productions. She has done other things, but this is enough. Julian Schlossberg Producer Julian Schlossberg is an award-winning theater, film and television producer. For TV, he’s produced for HBO, AMC and PBS, including American Masters — Nichols & May: Take Two and American Masters: The Lives of Lillian Hellman . Plays produced by Schlossberg have earned many honors, including six Tony Awards, two Obie Awards, seven Drama Desk Awards and five Outer Critics Circle Awards, among them Bullets Over Broadway: The Musical , The Beauty Queen of Leenane and Fortune’s Fool . He also produced six of Elaine May’s plays: Relatively Speaking , Adult Entertainment , After the Night and the Music , Power Plays , Death Defying Acts and Taller Than a Dwarf . -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

The Color of Money”

David Alciatore, PhD (“Dr. Dave”) ILLUSTRATED PRINCIPLES “Billiards on the Big Screen – The Color of Money” Note: Supporting narrated video (NV) demonstrations, high-speed video (HSV) clips, and technical proofs (TP) can be accessed and viewed online at billiards.colostate.edu. The reference numbers used in the article (e.g., NV A.7) help you locate the resources on the website. If you don’t have access to the Internet, or if you have a slow connection (e.g., a modem), you may want to view the resources from a CD-ROM instead. To order one, send a check or money order (payable to David Alciatore) for $21.45 (includes S&H) to: Pool Book CD; 626 S. Meldrum St.; Fort Collins, CO 80521. The CD-ROM is compatible with both PCs and MACs. This is the second article in my “Billiards on the Big Screen” series, where I illustrate and describe interesting shots from movies with major billiards themes. Last month, I presented some shots from the classic billiards flick: “The Hustler.” By the way, if you want to refer back to any of my previous articles and online resources, you can access them online at billiards.colostate.edu. This month’s article deals with the huge box-office success: “The Color of Money.” In my next two articles, I will show shots from “Pool Hall Junkies” and “Donald in Mathmagic Land.” ”The Color of Money” (1986, Touchstone Pictures) is the story of two hustlers who teach each other a few things about pool and life. Fast Eddie Felson (played by Paul Newman), a seasoned hustler, discovers Vincent (played by Tom Cruise), an immature and young hustler with great talent and potential. -

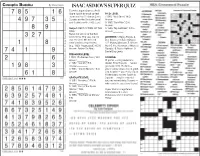

Isaac Asimov's Super Quiz

PAGE 6A WEDNESDAY, JULY 7, 2021 TIMES WEST VIRGINIAN ADVICE Dear Mayo Clinic Q and A: Simplify health Annie Annie Lane goals for success Syndicated Columnist that includes things such as: every other day with a meal. This can be By Cynthia Weiss – Ridding homes of any desserts, candy, something you can easily manage and Mayo Clinic News Network soda and processed food. feel successful with. Just remember not Dear Mayo Clinic: I am a mom of three – Promising to buy and eat only whole to overload it with dressing. Or instead of kids under 10, and I have struggled with foods made from scratch. grabbing a handful of chips for a snack, Twin brothers weight loss for years. I am challenged – Going to the gym five or more days a grab an apple or a cheese stick. Consider the between family and work obligations to week and working out for an hour each time. same substitutions for your children so you maintain a healthy lifestyle. I always start – Hiring a life coach to help get their life won’t be tempted. can’t get along off strong, but then I get overwhelmed and together. Over time, one change will lead to stop. Last month, despite trying to eat right – Reducing work stress. another. As you implement healthy things Dear Annie: I come from a big family. I and working out daily, I gained weight after Does this sound familiar? into your routine, you will build more have seven brothers and two sisters, and I’m two weeks instead of losing it. -

Painting En Abyme: Tracing the Uses of Painting in New Hollywood Cinema

PAINTING EN ABYME: TRACING THE USES OF PAINTING IN NEW HOLLYWOOD CINEMA By MICHELLE LYNN RINARD Bachelor of Arts in Art History Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2015 PAINTING EN ABYME: TRACING THE USES OF PAINTING IN NEW HOLLYWOOD CINEMA Thesis Approved: Dr. Louise Siddons Thesis Adviser Dr. Jeff Menne Dr. Rebecca Brienen ii Name: MICHELLE L. RINARD Date of Degree: MAY 2015 Title of Study: PAINTING EN ABYME: TRACING THE USES OF PAINTING IN NEW HOLLYWOOD CINEMA Major Field: ART HISTORY Abstract: In the period of the New Hollywood in cinema, four directors created films that incorporated paintings and artworks within their scenes: Mike Nichols’ The Graduate (1967); John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1966); Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971); and Paul Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman (1978). In four close readings, I demonstrate that these filmmakers incorporated painting to contribute to the emotions and narrative, to reflect the institutional power or ideological positions of characters and organizations, and as cultural or anti-cultural capital. The incorporation of painting in film creates a mise en abyme, doubling the forms and meanings of art within the film medium. The use of painting in cinema in the period between 1966 and 1978 is characteristic of an artistic trend in New Hollywood filmmaking. Earlier uses of art in film were overwhelmingly narrative and diegetic, while in New Hollywood film it becomes a mode of editorializing and extra diegetic commentary. -

The-Wall-Street-Bookie.Pdf

Introduction Options trading firm blows up amid natural gas volatility (source: FT) One millennial options trader was killing it, then Facebook cost him $180,000 (source: MarketWatch) Trader says he has “no money at risk,” then promptly loses almost 2,000% (source: MarketWatch) The headlines above are some of the reasons why financial advisors recommend that their clients stay away from options. Heck, for the majority of my trading career, I dabbled with them, with almost NO success. However, that all changed once I decided to switch my approach. Instead of buying like the sucker… like those folks who play slot machines at the casino… I began taking the other side— in turn, becoming the HOUSE. The casino strategy that I also call Weekly Windfalls puts you in the driver’s seat, as you’ll learn after reading this eBook. After reading it, you’ll learn: ● How to easily position yourself for success on a week-to-week basis utilizing the casino strategy. Even if you’ve never placed a single option trade in your life before. ● The No. 1 reason why traders fail at options trading. And how a switch in mindset can turn you from ready to give up to consistently profitable. ● How to stack the odds in your favor. Why put on a trade with one possible way to win when you can have THREE? ● The ultimate set it and forget it strategy. Decision fatigue is a real thing. I’ll teach you how to take the stress out of options trading. WALLST BOOKIE JASON BOND 2 ● How to profit in any market condition. -

Understanding Steven Spielberg

Understanding Steven Spielberg Understanding Steven Spielberg By Beatriz Peña-Acuña Understanding Steven Spielberg Series: New Horizon By Beatriz Peña-Acuña This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Beatriz Peña-Acuña Cover image: Nerea Hernandez Martinez All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0818-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0818-7 This text is dedicated to Steven Spielberg, who has given me so much enjoyment and made me experience so many emotions, and because he makes me believe in human beings. I also dedicate this book to my ancestors from my mother’s side, who for centuries were able to move from Spain to Mexico and loved both countries in their hearts. This lesson remains for future generations. My father, of Spanish Sephardic origin, helped me so much, encouraging me in every intellectual pursuit. I hope that contemporary researchers share their knowledge and open their minds and hearts, valuing what other researchers do whatever their language or nation, as some academics have done for me. Love and wisdom have no language, nationality, or gender. CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 3 Spielberg’s Personal Context and Executive Production Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 19 Spielberg’s Behaviour in the Process of Film Production 2.1. -

Hollywood Goes to Tokyo: American Cultural Expansion and Imperial Japan, 1918–1941

HOLLYWOOD GOES TO TOKYO: AMERICAN CULTURAL EXPANSION AND IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1918–1941 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yuji Tosaka, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Michael J. Hogan, Adviser Dr. Peter L. Hahn __________________________ Advisor Dr. Mansel G. Blackford Department of History ABSTRACT After World War I, the American film industry achieved international domi- nance and became a principal promoter of American cultural expansion, projecting images of America to the rest of the world. Japan was one of the few countries in which Hollywood lost its market control to the local industry, but its cultural exports were subjected to intense domestic debates over the meaning of Americanization. This dis- sertation examines the interplay of economics, culture, and power in U.S.-Japanese film trade before the Pacific War. Hollywood’s commercial expansion overseas was marked by internal disarray and weak industry-state relationships. Its vision of enlightened cooperation became doomed as American film companies hesitated to share information with one another and the U.S. government, while its trade association and local managers tended to see U.S. officials as potential rivals threatening their positions in foreign fields. The lack of cooperation also was a major trade problem in the Japanese film market. In general, American companies failed to defend or enhance their market position by joining forces with one another and cooperating with U.S. officials until they were forced to withdraw from Japan in December 1941.