The Name on the Wall By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Body and Soul: Queering the Western Romance Novella University Of

Body and Soul: Queering the Western Romance Novella by Kay Bowring A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Manitoba V/innipeg Copyright O 2006 by Kay Bowring THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACTILTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES COPYRIGHT PERMISSION Body and Soul: Queering the Western Romance Novella by Kay Bowring A Thesis/Practicum submitted to the tr'aculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfitlment of the requirement of the degree of Master of Arts Kay Bowring @ 2006 Permission has been granted to the Library of the University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Library of Canada to microfilm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and to University Microfitms Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. This reproduction or copy of this thesis/practicum has been made available by authority of the copyrigh[ owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced aná copleA as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright ovvner. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1t Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Alison Calder, for her patience and assistance over the past three years. Her comments, insights and ideas have proven to be an invaluable asset to me in completing this project. Additionally, I would to thank Dr. Robin Jarvis Brownlie and Dr. -

ABSTRACT Beck Boots: the Story of Cowboy Boots in the Texas

ABSTRACT Beck Boots: The Story of Cowboy Boots in the Texas Panhandle and Their Important Role in American Life Tye E. Barrett, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon Jr., Ph.D. Merton McLaughlin moved to the Texas Panhandle and began making cowboy boots in the spring of 1882. Since that time, cowboy boots have been a part of the Texas Panhandle’s, and America’s rich history. In 1921, twin brothers Earl and Bearl Beck purchased McLaughlin’s boot shop. The Beck family has been making cowboy boots in the Texas Panhandle ever since. This thesis seeks not only to present a history of Beck Boots and cowboy boots in the Texas Panhandle, but also suggests that the relationship between bootmakers, like Beck Boots, and the working cowboy has been the center of success to the business of bootmakers and cowboys alike. Because many, like the Beck family, have nurtured this relationship, cowboy boots have become a central theme and important icon in American life. Beck Boots: The Story of Cowboy Boots in the Texas Panhandle and Their Important Role in American Life by Tye E. Barrett, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Barry G. Hankins, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Sara J. Stone, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2010 ___________________________________ J. -

2022-23 Megastructures Museum V1.Indd

Bringing history to life MEGASTRUCTURES FORCED LABOR AND MASSIVE WORKS IN THE THIRD REICH Hamburg • Neuengamme • Binz • Peenemünde • Szczecin Wałcz • Bydgoszcz • Łódź • Treblinka • Warsaw JULY 7–18, 2022 Featuring Best-selling Author & Historian Alexandra Richie, DPhil from the Pomeranian Photo: A view from inside a bunker Courtesy of Nathan Huegen. Poland. near Walcz, Wall Save $1,000 per couple when booked by January 18, 2022! THE NATIONAL WWII MUSEUM EDUCATIONAL TRAVEL PROGRAM Senior Historian, Author, and Museum Presidential Counselor, Alexandra Richie, DPhil Dear Friend of the Museum, Since 2015, I have been leading The Rise and Fall of Hitler’s Germany, a tour from Berlin Travel to to Warsaw with visits to Stalag Luft III, Wolf’s Lair, Krakow, and more. As we look ahead to the future, I am excited to expand the tours in Poland, visiting a number of largely Museum unexplored sites. Quick Facts 27 The all-new tour is named Megastructures after many of the large complexes we visit 5 countries covering such as Peenemünde, the Politz Synthetic Oil Factory, and numerous gun batteries 8 million+ all theaters and bunkers. As we tour, we will pause to remember the forced laborers who visitors since the Museum of World War II suffered under Nazi oppression. We will learn of the prisoners at the Neuengamme opened on June 6, 2000 Concentration Camp near Hamburg who, at first, manufactured construction materials, then transitioned into the main force that cleared the city’s rubble and $2 billion+ Tour Programs operated bodies after the devastating bombing raids of 1943. in economic impact on average per year, at In Prora, we will explore the Nazi’s “Strength through Joy” initiative when we view times accompanied by the three-mile-long resort that was never completed. -

Our Oflag 64 Website Has a New Name…

The Nearly Everybody Your Quiet Hour Reads The ITEM Companion “Get Wise – ITEM-ize” 1st Quarter 2019 Good Ole USA Of Undetermined Worth Editor/Printing and Mailing Elodie Caldwell 2731 TERRY AVE LONGVIEW WA 98632-4437 [email protected] Treasurer Bret Job 2801 SW 46th ST CAPE CORAL FL 33914 -6026 [email protected] Drawing by Jim Bickers, shown without barbed wire fences or guard towers Webmaster/Blogger Bill Caldwell 2731 TERRY AVE Our Oflag 64 website has a new name…. LONGVIEW WA 98632-4437 [email protected] ….but you can still find it by typing our web address www.oflag64.us or Oflag 64 in your browser’s search bar. The change from Oflag 64 Association to Oflag 64 Contributors to this issue Remembered was made to more accurately reflect our site’s objective. The same Andy Baum content will still be available with periodic updates, but nothing else except renaming Patricia Bender the site has been done. We think you’ll agree that this is a great change and long Claire Anderson Bowlby overdue. Cindy Burgess Glenn Burgess Tom Cobb Susanna Connaughton Terrence Dooley Susan Hinds Harms Victoria Herring Bret Job Lynn Kanaya Pam Ladley Rosa Lee Also, because our Oflag 64 family is not actually an official association per se, but a Marlene McAllister group of people with the same interests, we will be begin referring to ourselves as The Stephanie Phelan Oflag 64 Family rather than the Oflag 64 Association. This will also help us distinguish Robert Rankin, Jr. our group from the recently formed Oflag 64 Foundation which is working diligently on Dave Stewart the newly named “Museum of POW Camps in Szubin” project. -

Oflag XIII-B (13-B) Following Courtsey of Wikipedia

Oflag XIII-B (13-B) Following courtsey of Wikipedia Oflag XIII-B was a German Army World War II prisoner-of-war camp for officers (Offizierslager), originally in the Langwasser district of Nuremberg. In 1943 it was moved to a site 3 km (1.9 mi) south of the town of Hammelburg in Lower Franconia, Bavaria, Germany. Lager Hammelburg ("Camp Hammelburg") was a large German Army training camp, opened in 1873. Part of this camp had been used as a POW camp for Allied army personnel during World War I. After 1935 it was a training camp and military training area for the newly reconstituted Army. In World War II the Army used parts of Camp Hammelburg for Oflag XIII-B. It consisted of stone buildings. Stalag XIII-C for other ranks and NCOs was located close by. In May 1941 part of Oflag XIII-A Langwasser, Nuremberg, was separated off, and a new camp, designated Oflag XIII- B, created for Yugoslavian officers, predominantly Serbs captured in the Balkans Campaign. In April 1943 at least 3,000 Serbian officers were moved from Langwasser to Hammelburg. Many were members of the Yugoslavian General Staff, some of whom had been POWs in Germany during the First World War. On 11 January 1945 American officers captured during the Battle of the Bulge arrived and were placed in a separate compound. One of these was Lt. Donald Prell, Anti-tank platoon, 422nd Infantry, 106th Division. By 25 January the total number of Americans was 453 officers, 12 non-commissioned officers and 18 privates. On 10 March 1945 American officers, captured in the North Africa Campaign in 1943 or the Battle of Normandy, arrived after an eight-week 400 mi (640 km) forced march from Oflag 64 in Szubin, Poland. -

Battle Analysis: the Hammelburg Incident – Patton's Last Controversy

Battle Analysis: The Hammelburg Incident – Patton’s Last Controversy by retired LTC Lee F. Kichen LTG George S. Patton Jr.’s reputation as one of America’s greatest battlefield commanders is virtually unquestioned. He was a brilliant tactician, audacious and flamboyant. The infamous slapping incidents and the ensuing publicity firestorm hardly tarnished his reputation as a fighting general. However, his decision to liberate 900 American prisoners of war (POWs) confined in Offizerslager (Oflag) XIIIB near Hammelburg, Germany, was more than an embarrassment, it was the most controversial and worst tactical decision of his career.1 Central to the controversy are lingering questions: Was the decision to raid Oflag XIIIB morally justifiable and tactically sound? What are the lessons for today’s mounted warriors when planning and conducting a deep raid? Did Patton order this raid based on credible intelligence that his son-in-law, LTC John K. Waters, was a prisoner in Oflag XIIIB? Would he have ordered the raid if he had not thought that Waters would likely be there? Or was it intended as a diversionary attack to deceive the enemy that Third Army was attacking east, not north? The answer to what truly motivated Patton to order the ill-fated raid on Hammelburg remains unsettled history. However, the evidence is inconvertible that the raid’s failure resulted from flawed planning by Patton and his subordinate commanders. Personal background Patton repeatedly avowed that he didn’t know for certain that Waters was in Oflag XIIIB. Yet the evidence is overwhelming that Patton knew that Waters was at Hammelburg. -

German Documents Among the War Crimes Records of the Judge Advocate Division, Headquarters, United States Army, Europe

Publication Number: T-1021 Publication Title: German Documents Among the War Crimes Records of the Judge Advocate Division, Headquarters, United States Army, Europe Date Published: 1967 GERMAN DOCUMENTS AMONG THE WAR CRIMES RECORDS OF THE JUDGE ADVOCATE DIVISION, HEADQUARTERS, UNITED STATES ARMY, EUROPE Introduction Many German documents from the World War II period are contained in the war crimes case files of Headquarters, United States Army Europe (HQ USAREUR), Judge Advocate Division, dated 1945-58. These files contain transcripts of trial testimony, clemency petitions, affidavits, prosecution exhibits, photographs of concentration camps, etc., as well as original German documents used as evidence in the prosecution of the numerous war crimes cases, excluding the Nuremberg Trials, concerning atrocities in concentration camps, atrocities committed on Allied military personnel and Allied fliers who crash landed in Germany, and other crimes. Only the German documents predating May 8, 1945, have been included in this filming project. A data sheet describing the material in each folder microfilmed is included before the items filmed. The Judge Advocate Division file number has been used to identify each item wherever given. In other instances whatever identifying information is available, such as the case or exhibit number, has been given as the item number. Overall provenance for the records is HQ USAREUR. Judge Advocate Division, as all German documents in the files were made a permanent part of the records of that office; however, the original German provenance of the items filmed is given as the provenance on the data sheets. CONTENTS Roll Description 1 000-50-2, Vol. 1 [No Title] Correspondence, reports, memoranda, scientific theses, and other data exchanged among Dr. -

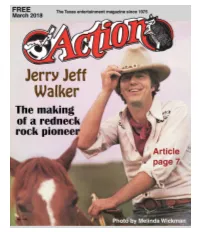

Jerry Jeff Walker

Spring Specials www.Brookspub.biz March E NTERTAINMENT Kids square toe boots FRI 2nd RAD FRI 23rd Prototype 10% OFF FRI 9th MTO FRI 30th GTB (Get The Belt) FRI 16th Spitfire Ladies Corral boots Happy St. Patricks Day 10% OFF 17th Drink Specials All western belts are 20% OFF Mens & Ladies Durango boots $10 OFF All Stetson & Resistol Mens Ariat boots straw hats 15% OFF $10 OFF Daily Drink Specials Everyday! Ask one www.cowtownboots.com of our beautiful bartenders for details. 4522 Fredericksburg Road G San Antonio, Texas G 210.736.0990 • 2 • Action Magazine, March 2018 advertising is worthless if you have nothing worth advertising Put your money where the music is. Advertise in Action Magazine • DEPARTMENTS • Music Matters ........................................4 Editor & Publisher ................Sam Kindrick Sam Kindrick ..........................................6 Advertising Sales ....................Action Staff Photography.............................Action Staff Scatter Shots ........................................11 Distribution............................Ronnie Reed Composition..........................Elise Taquino Volume 43 • Number 3 • FEATURE • Jerry Jeff Walker ......................................7 Green Machine ......................................12 Action Magazine, March 2018 • 3 • Chesnut says ‘stop and smell the music’ I have been performing end of a good-time Satur - Blanco Road in San Anto - formers, on the other There are countless performance. In my opin - live country music full-time day night. Nothing much nio. As it turns out, those hand, are depending on other venues and perform - ion, traffic noises from or part-time since 1969. I surprises me. folks love country music. the venue to have a crowd ers in synergistic relation - congested roadways have performed on stages But, much to my sur - After my cancer diag - that will add to the per - ships throughout the city, would be a lot harder to behind chicken wire, prise few years back I nosis last summer, I was former’s income and num - but no amount of synergy deal with. -

2Nd Quarter-2019.Pdf

The Nearly Everybody Your Quiet Hour Reads The ITEM Companion “Get Wise – ITEM-ize” 2nd Quarter 2019 Good Ole USA Of Undetermined Worth Editor/Printing and Mailing Elodie Caldwell 2731 TERRY AVE LONGVIEW WA 98632-4437 [email protected] Treasurer Bret Job 2801 SW 46th ST CAPE CORAL FL 33914-6026 [email protected] Drawing by Jim Bickers, shown without barbed wire fences or guard towers Webmaster/Blogger Bill Caldwell 2731 TERRY AVE DID YOU KNOW THAT…… LONGVIEW WA 98632-4437 [email protected] …. the Oflag 64 Remembered website, The Polish-American Foundation for the Commemoration of POW Camps in Szubin, the blog for the Museum of POW Camps Contributors to this issue in Szubin, and the Friends of Oflag 64, Inc. nonprofit are all working together? Cindy Burgess Glenn Burgess The Oflag 64 Remembered website is the historical arm of Oflag 64 and brings Tom Cobb together families, friends, and researchers who share a passion for learning about the Susanna Connaughton experiences of the POWs of Oflag 64. Through its website, newsletters, and informal Randolph Holder reunions, Oflag 64 Remembered maintains the ties that created The Oflag 64 Family. Bret Job The Polish-American Foundation for the Commemoration of POW Camps in Szubin Anne Hoskot Kreutzer is the working arm involved in creating the Museum of POW Camps in Szubin. The Rosa Lee Foundation will soon launch their website dedicated to the various POW camps that Marlene McAllister were located in Szubin during all of WWII. John R. Rodgers, Sr. Ted Roggen The Blog for the Museum of POW Camps in Szubin is the publicity arm of the Dave Stewart Museum project. -

Disruption of Freedom: Life in Prisoner of War Camps in Europe 1939-1945

Stacey Astill Disruption of Freedom: Life in Prisoner of War Camps in Europe 1939-1945 This paper will explore the disruptive nature of Prisoner of War (POW) life, and comparatively analyse responses to their captive experience by taking a ‘cross camp’ approach, exploring a wide cross section of POW camps in Europe under both German and Italian control. I will consider the culture of prison camps, and the actions of men in the face of this tumultuous period in their lives by drawing on war diaries - both contemporary and retrospective - oral testimony, objects from camp, contemporary and academic articles, and photographs or sketches.1 This overarching method is to be used in tandem with previous research, building on the individual explorations of specific camps or specific activities. Although there have previously been detailed investigations into specific camps such as Colditz, and specific themes such as sport or theatre in POW camps, there is no current comparative analysis thereof. Viewing camps as a whole allows an analysis of common occurrences, and anomalous areas within them. These features can then be considered in terms of the camp conditions, the time period for which the camp existed, who controlled the camp, and where it was located. The following analysis therefore offers a broader assessment, drawing together a range of source material to provide a comparative view of a variety of camp experiences. Becoming a POW was at least the second major disruption in prisoners’ lives, the first being the war itself. Even career soldiers experienced a change with the outbreak of the Second World War; they were in the military, but no existing conflict was similar in scale to that of the Second World War. -

Of Wonders Wild and New

H^v~ . ^^H • Of Wonders Wild and New DREAMS FROM ZINACANTAN •, I Robert M. Laughlin '.c'v/ - HHH SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ANTHROPOLOGY NUMBER 22 SERIAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION The emphasis upon publications as a means of diffusing knowledge was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. In his formal plan for the Insti tution, Joseph Henry articulated a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This keynote of basic research has been adhered to over the years in the issuance of thousands of titles in serial publications under the Smithsonian imprint, com mencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Annals of Flight Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes original articles and monographs dealing with the research and collections of its several museums and offices and of profes sional colleagues at other institutions of learning. These papers report newly acquired facts, synoptic interpretations of data, or original theory in specialized fields. These publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, laboratories, and other in terested institutions and specialists throughout the world. Individual copies may be obtained from the Smithsonian Institution Press as long as stocks are available. -

The Roman Traitor (Vol. 1 of 2) by Henry William Herbert

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Roman Traitor (Vol. 1 of 2) by Henry William Herbert This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.guten- berg.org/license Title: The Roman Traitor (Vol. 1 of 2) Author: Henry William Herbert Release Date: April 18, 2008 [Ebook 25092] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ROMAN TRAITOR (VOL. 1 OF 2)*** [1] THE ROMAN TRAITOR: OR THE DAYS OF CICERO, CATO AND CATALINE. ii The Roman Traitor (Vol. 1 of 2) A TRUE TALE OF THE REPUBLIC. BY HENRY WILLIAM HERBERT AUTHOR OF "CROMWELL," "MARMADUKE WYVIL," "BROTHERS," ETC. iii Why not a Borgia or a Catiline?—POPE. iv The Roman Traitor (Vol. 1 of 2) VOLUME I. This is one of the most powerful Roman stories in the English language, and is of itself sufficient to stamp the writer as a powerful man. The dark intrigues of the days which Cæsar, Sallust and Cicero made illustrious; when Cataline defied and almost defeated the Senate; when the plots which ultimately overthrew the Roman Republic were being formed, are described in a masterly manner. The book deserves a permanent position by the side of the great Bellum Catalinarium of Sallust, and if we mistake not will not fail to occupy a prominent place among those produced in America. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson, NO.