Indemnification Indemnification in a Stock Purchase Agreement Asimplemodel.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Law and Legal Reasoning Law Is

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND LEGAL REASONING LAW IS "MAN MADE" IT CHANGES OVER TIME TO ACCOMMODATE SOCIETY'S NEEDS LAW IS MADE BY LEGISLATURE LAW IS INTERPRETED BY COURTS TO DETERMINE 1)WHETHER IT IS "CONSTITUTIONAL" 2)WHO IS RIGHT OR WRONG THERE IS A PROCESS WHICH MUST BE FOLLOWED (CALLED "PROCEDURAL LAW") I. Thomas Jefferson: "The study of the law qualifies a man to be useful to himself, to his neighbors, and to the public." II. Ask Several Students to give their definition of "Law." A. Even after years and thousands of dollars, "LAW" still is not easy to define B. What does law Consist of ? Law consists of enforceable rule governing relationships among individuals and between individuals and their society. 1. Students Need to Understand. a. The law is a set of general ideas b. When these general ideas are applied, a judge cannot fit a case to suit a rule; he must fit (or find) a rule to suit the unique case at hand. c. The judge must also supply legitimate reasons for his decisions. C. So, How was the Law Created. The law considered in this text are "man made" law. This law can (and will) change over time in response to the changes and needs of society. D. Example. Grandma, who is 87 years old, walks into a pawn shop. She wants to sell her ring that has been in the family for 200 years. Grandma asks the dealer, "how much will you give me for this ring." The dealer, in good faith, tells Grandma he doesn't know what kind of metal is in the ring, but he will give her $150. -

Beyond Unconscionability: the Case for Using "Knowing Assent" As the Basis for Analyzing Unbargained-For Terms in Standard Form Contracts

Beyond Unconscionability: The Case for Using "Knowing Assent" as the Basis for Analyzing Unbargained-for Terms in Standard Form Contracts Edith R. Warkentinet I. INTRODUCTION People who sign standard form contracts' rarely read them.2 Coun- sel for one party (or one industry) generally prepare standard form con- tracts for repetitive use in consecutive transactions.3 The party who has t Professor of Law, Western State University College of Law, Fullerton, California. The author thanks Western State for its generous research support, Western State colleague Professor Phil Merkel for his willingness to read this on two different occasions and his terrifically helpful com- ments, Whittier Law School Professor Patricia Leary for her insightful comments, and Professor Andrea Funk for help with early drafts. 1. Friedrich Kessler, in a pioneering work on contracts of adhesion, described the origins of standard form contracts: "The development of large scale enterprise with its mass production and mass distribution made a new type of contract inevitable-the standardized mass contract. A stan- dardized contract, once its contents have been formulated by a business firm, is used in every bar- gain dealing with the same product or service .... " Friedrich Kessler, Contracts of Adhesion- Some Thoughts About Freedom of Contract, 43 COLUM. L. REV. 628, 631-32 (1943). 2. Professor Woodward offers an excellent explanation: Real assent to any given term in a form contract, including a merger clause, depends on how "rational" it is for the non-drafter (consumer and non-consumer alike) to attempt to understand what is in the form. This, in turn, is primarily a function of two observable facts: (1) the complexity and obscurity of the term in question and (2) the size of the un- derlying transaction. -

Contracts Outline

Contracts Outline NYU Fall 2004, Professor Barry Friedman Chapter 1 What Promise Ought We Enforce.............................................................. 8 1. Why we enforce promise......................................................................................... 8 1.1. Moral claim (Foundational) ........................................................................ 8 1.2. Efficiency / Mutual exchange: we can not exchange things simultaneously.............................................................................................. 8 1.3. Reliance: somebody relies on the promise and changes his plan............. 8 1.4. Will theory: somebody makes the promise means he wants the promise to be enforced. .............................................................................................. 8 1.5. Benefits unjustly retained............................................................................ 8 2. Promise with good consideration........................................................................... 8 2.1. Bargain for exchange is the test of good consideration ............................ 8 2.2. Past consideration is no good consideration.............................................. 9 2.3. Moral promise could be enforced under material benefit rule................ 9 2.4. Illusory promise is no good consideration ................................................. 9 2.5. Conditional promise could be good consideration.................................. 10 2.6. Good consideration could be implied...................................................... -

Important Concepts in Contract

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Practical concepts in Contract Law Ehsan, zarrokh 14 August 2008 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/10077/ MPRA Paper No. 10077, posted 01 Jan 2009 09:21 UTC Practical concepts in Contract Law Author: EHSAN ZARROKH LL.M at university of Tehran E-mail: [email protected] TEL: 00989183395983 URL: http://www.zarrokh2007.20m.com Abstract A contract is a legally binding exchange of promises or agreement between parties that the law will enforce. Contract law is based on the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda (literally, promises must be kept) [1]. Breach of a contract is recognised by the law and remedies can be provided. Almost everyone makes contracts everyday. Sometimes written contracts are required, e.g., when buying a house [2]. However the vast majority of contracts can be and are made orally, like buying a law text book, or a coffee at a shop. Contract law can be classified, as is habitual in civil law systems, as part of a general law of obligations (along with tort, unjust enrichment or restitution). Contractual formation Keywords: contract, important concepts, legal analyse, comparative. The Carbolic Smoke Ball offer, which bankrupted the Co. because it could not fulfill the terms it advertised In common law jurisdictions there are three key elements to the creation of a contract. These are offer and acceptance, consideration and an intention to create legal relations. In civil law systems the concept of consideration is not central. In addition, for some contracts formalities must be complied with under what is sometimes called a statute of frauds. -

Deterring Nuisance Suits Through Employee Indemnification

Deterring Nuisance Suits through Employee Indemnification Wallace P. Mullin Department of Economics, George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052. Email: [email protected]. Christopher M. Snyder Department of Economics, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755. Email: [email protected]. March 8, 2010 Abstract: Broad employee indemnification is pervasive among corporations. Indemnification covers individual sanctions, such as fines, for corporate actions. These guarantees that are not merely tolerated but indeed encouraged by public policy. We offer a new rationale for widespread indemnification. Indemnification deters meritless civil suits by strengthening employees’ resolve to fight them. Keywords: indemnification, litigation, settlement bargaining Acknowledgements: The authors thank Ian Ayres, Tracy Lewis, and seminar participants at the George Washington University, International Industrial Organization Conference (Boston, 2009), University of Melbourne, and the University of Sydney Economics of Organizations Conference for helpful comments. 1. Introduction Litigation against corporations and their officers and directors is a major industry. While some of these lawsuits may be useful to society, it is feared that a fraction are so called “nuisance suits.” These suits are motivated solely by the prospect of extracting settlement payments. A logical strategic response by targeted corporations would be to strengthen their bargaining position against such plaintiffs in the settlement negotiations. According to a recent survey, 98 percent of U.S. firms with over 500 shareholders had third party D&O (director and officer) insurance (Tillinghast-Towers Perrin 2002). One interpretation of broad indemnification is that the firm (or shareholders) will absorb fines and settlements ostensibly levied against officers and directors. The most direct rationale for widespread indemnification is that it shares risk between risk neutral shareholders and risk averse officers and directors. -

Contract Formation Under Article 2 of the Uniform Commerical Code Carolyn M

Marquette Law Review Volume 61 Article 1 Issue 2 Winter 1977 Contract Formation Under Article 2 of the Uniform Commerical Code Carolyn M. Edwards Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Carolyn M. Edwards, Contract Formation Under Article 2 of the Uniform Commerical Code, 61 Marq. L. Rev. 215 (1977). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol61/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW Vol. 61 Winter 1977 No. 2 CONTRACT FORMULATION UNDER ARTICLE 2 OF THE UNIFORM COMMERCIAL CODE CAROLYN M. EDWARDS* Today, Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code' is the principal statute governing sales of goods2 in every state except Louisiana. Although the article made fundamental changes in the law of sales, it did not totally displace common law princi- ples. Indeed, some provisions of the statute codify common law rules. The shortcoming of the statute, however, is that it is not self-executing; it is silent on some issues and ambiguous as to others. Under these circumstances courts have resorted to com- mon law, citing Article 1, section 1-103,1 which provides that the principles of law and equity may supplement the Code unless such principles are displaced by particular provisions. * Assistant Professor of Law, Marquette University Law School; B.A. -

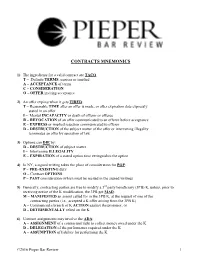

Contracts Mnemonics

CONTRACTS MNEMONICS 1) The ingredients for a valid contract are TACO: T – Definite TERMS, express or implied A – ACCEPTANCE of terms C – CONSIDERATION O – OFFER inviting acceptance 2) An offer expires when it gets TIRED: T – Reasonable TIME after an offer is made, or after expiration date expressly stated in an offer I – Mental INCAPACITY or death of offeror or offeree R – REVOCATION of an offer communicated to an offeree before acceptance E – EXPRESS or implied rejection communicated to offeror D – DESTRUCTION of the subject matter of the offer or intervening illegality terminates an offer by operation of law 3) Options can DIE by: D – DESTRUCTION of subject matter I – Intervening ILLEGALITY E – EXPIRATION of a stated option time extinguishes the option 4) In NY, a signed writing takes the place of consideration for POP: P – PRE–EXISTING duty O – Contract OPTIONS P – PAST consideration (which must be recited in the signed writing) 5) Generally, contracting parties are free to modify a 3rd party beneficiary (3PB) K, unless, prior to receiving notice of the K modification, the 3PB got MAD: M – MANIFESTED an assent called for in the 3PB K, at the request of one of the contracting parties (i.e., accepted a K offer arising from the 3PB K) A – Commenced a breach of K ACTION against the promisor, or D – DETRIMENTALLY relied on the K 6) Contract assignments may involve the ADA: A – ASSIGNMENT of a contractual right to collect money owed under the K D – DELEGATION of the performance required under the K A – ASSUMPTION of liability for performing -

CULPA in CONTRAHENDO, BARGAINING in GOOD FAITH, and FREEDOM of CONTRACT: a COMPARATIVE STUDY Friedrichkessler * and Edith Fine **

VOLUME 77 JANUARY 1964 NUMBER 3 HARVARD LAW REVIEW CULPA IN CONTRAHENDO, BARGAINING IN GOOD FAITH, AND FREEDOM OF CONTRACT: A COMPARATIVE STUDY FriedrichKessler * and Edith Fine ** The common law appears to have no counterpart to the German doctrine of culpa in contrahendo: that contractingparties are under a duty, classified as contractual, to deal in good faith with each other during the negotiation stage, or else face liability, customarily to the extent of the wronged party's reliance. In this comparative study Professor Kessler and Mrs. Fine find, however, that notions of good faith and fair dealing are frequently expressed in the American contract law affecting preliminary negotiations,firm offers, mistake, and misrepresentation, and that the doctrines of negli- gence, estoppel, and implied contract, among others, have at the same time served many of the doctrinal functions of culpa in con- trahendo. I. INTRODUCTION T HE doctrine of culpa in contrahendo goes back to a famous article by Jhering, published in i86i, entitled "Culpa in con- trahendo, oder Schadensersatz bei nichtigen oder nicht zur Per- fektion gelangten Vertrdgen." ' It advanced the thesis that dam- ages should be recoverable against the party whose blameworthy conduct during negotiations for a contract brought about its in- validity or prevented its perfection. Its impact has reached be- yond the German law of contracts. *'Justus S. Hotchkiss Professor of Law, Yale Law School. J.U.D., University of Berlin, 1928. The authors gratefully acknowledge the constructive suggestions made by Sonja Goldstein, B.Sc. (econ.), London School of Economics, '947; LL.B., Yale, 1952. "A.B., Barnard, i95i; LL.B., Harvard, 1957. -

Genworth Financial Inc

GENWORTH FINANCIAL INC FORM 8-K (Current report filing) Filed 05/21/14 for the Period Ending 05/15/14 Address 6620 WEST BROAD STREET RICHMOND, VA 23230 Telephone 804-281-6000 CIK 0001276520 Symbol GNW SIC Code 6311 - Life Insurance Industry Insurance (Life) Sector Financial Fiscal Year 12/31 http://www.edgar-online.com © Copyright 2014, EDGAR Online, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and use of this document restricted under EDGAR Online, Inc. Terms of Use. UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 May 15, 2014 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported) GENWORTH FINANCIAL, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001 -32195 80 -0873306 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission (I.R.S. Employer of incorporation) File Number) Identification No.) 6620 West Broad Street, Richmond, VA 23230 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (804) 281-6000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) N/A (Former name or former address, if changed since last report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions (see General Instruction A.2 below): Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a -12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a -12) Pre -commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d -2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d -2(b)) Pre -commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e -4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e -4(c)) Item 1.01 Entry into a Material Definitive Agreement. -

The Economics of Promissory Estoppel in Preliminary Negotiations

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 1996 When Should an Offer Stick? The Economics of Promissory Estoppel in Preliminary Negotiations Avery W. Katz Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, Contracts Commons, and the Law and Economics Commons Recommended Citation Avery W. Katz, When Should an Offer Stick? The Economics of Promissory Estoppel in Preliminary Negotiations, 105 YALE L. J. 1249 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/266 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When Should an Offer Stick? The Economics of Promissory Estoppel in Preliminary Negotiations Avery Katzt CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................... 1250 A. The Regulatory Role of ContractFormation Law ......... 1250 B. PromissoryEstoppel and the Regulation of Reliance ...... 1253 II. THE LEGAL PROBLEM ............................... 1259 A. The Doctrinal Background ........................ 1259 B. Critique of the TraditionalApproach ................. 1263 IT[. THE UNDERLYING ECONOMIC PROBLEM ................... 1267 A. The Planning Problem ........................... 1267 B. The -

Contracts & Sales

CONTRACTS & SALES BARBRI BOOK EXAMPLE CONTRACTS AND SALES i. CONTRACTS AND SALES TABLE OF CONTENTS I. WHAT IS A CONTRACT? . 1 A. GENERAL DEFINITION . 1 B. COMMON LAW VS. ARTICLE 2 SALE OF GOODS . 1 1. “Sale” Defined . 1 2. “Goods” Defined . 1 3. Contracts Involving Goods and Nongoods . 1 4. Merchants vs. Nonmerchants . 1 C. TYPES OF CONTRACTS . 1 1. As to Formation . 1 a. Express Contract . 1 b. Implied in Fact Contract . 2 c. Quasi-Contract or Implied in Law Contract . 2 2. As to Acceptance . 2 a. Bilateral Contracts—Exchange of Mutual Promises . 2 b. Unilateral Contracts—Acceptance by Performance . 2 c. Modern View—Most Contracts Are Bilateral . 2 1) Acceptance by Promise or Start of Performance . 2 2) Unilateral Contracts Limited to Two Circumstances . 2 3. As to Validity . 3 a. Void Contract . 3 b. Voidable Contract . 3 c. Unenforceable Contract . 3 D. CREATION OF A CONTRACT . 3 II. MUTUAL ASSENT—OFFER AND ACCEPTANCE . 3 A. IN GENERAL . 3 B. THE OFFER . 3 1. Promise, Undertaking, or Commitment . 4 a. Language . 4 b. Surrounding Circumstances . 4 c. Prior Practice and Relationship of the Parties . 4 d. Method of Communication . 4 1) Use of Broad Communications Media . 4 2) Advertisements, Etc. 4 e. Industry Custom . 5 2. Definite and Certain Terms . 5 a. Identification of the Offeree . 5 b. Definiteness of Subject Matter . 5 1) Requirements for Specific Types of Contracts . 5 a) Real Estate Transactions—Land and Price Terms Required . 5 b) Sale of Goods—Quantity Term Required . 5 (1) “Requirements” and “Output” Contracts . 6 (a) Quantity Cannot Be Unreasonably Disproportionate . -

The Law of Sales Huggard Art 2 00 Fmt.Qxp 10/17/19 10:17 AM Page Ii Huggard Art 2 00 Fmt.Qxp 10/17/19 10:17 AM Page Iii

huggard art 2 00 fmt.qxp 10/17/19 10:17 AM Page i The Law of Sales huggard art 2 00 fmt.qxp 10/17/19 10:17 AM Page ii huggard art 2 00 fmt.qxp 10/17/19 10:17 AM Page iii The Law of Sales A DETAILED EXPLANATION OF ARTICLE 2 OF THE UNIFORM COMMERCIAL CODE John P. Huggard, J.D. Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina huggard art 2 00 fmt.qxp 10/17/19 10:17 AM Page iv Copyright © 2020 John P. Huggard All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Names: Huggard, John Parker, author. Title: The law of sales : a detailed explanation of Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code / by John P. Huggard. Description: Durham, North Carolina : Carolina Academic Press, LLC, 2019. | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019032380 | ISBN 9781531017668 (paperback) | ISBN 9781531017675 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH : Uniform commercial code. Sales. | Sales--United States--States. Classification: LCC KF912.24 1951 H84 2019 | DDC 346.7307/2--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019032380 Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America huggard art 2 00 fmt.qxp 10/17/19 10:17 AM Page v Contents Preface xix Acknowledgments xxi About the Author xxiii C HAPTER 1 The Background and Objectives of Article 2 3 § 101. Introduction 3 § 102. Definitions 4 § 103. A Brief Background of Article 2 5 § 104. Article 2’s Objectives 6 § 105.