"PRIVACY COULD Ontyobe HAD in PUBLIC": FORGING a GAY WORLD in the STREETS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Agenda Development Commission

AGENDA DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION ZONING MEETING CITY OF COLUMBUS, OHIO SEPTEMBER 11, 2014 The Development Commission of the City of Columbus will hold a public hearing on the following applications on Thursday, SEPTEMBER 11, 2014, beginning at 6:00 P.M. at the CITY OF COLUMBUS, I-71 NORTH COMPLEX at 757 Carolyn Avenue, Columbus, OH 43224 in the lower level HEARING ROOM. Further information may be obtained by visiting the City of Columbus Zoning Office website at http://www.columbus.gov/bzs/zoning/Development-Commission or by calling the Department of Building and Zoning Services, Council Activities section at 645-4522. THE FOLLOWING APPLICATIONS WILL BE HEARD ON THE 6:00 P.M. AGENDA: 1. APPLICATION: Z14-023 (14335-00000-00348) Location: 4873 CLEVELAND AVENUE (43229), being 0.675± acres located on the northwest corner of Cleveland Avenue and Edmonton Road (010-138823; Northland Community Council). Existing Zoning: SR, Suburban Residential District. Request: C-2, Commercial District. Proposed Use: Office development. Applicant(s): Everyday People Ministries; c/o Michael A. Moore, Agent; 1599 Denbign Drive; Columbus, Ohio 43220. Property Owner(s): The Applicant. Planner: Tori Proehl, 645-2749, [email protected] 2. APPLICATION: Z14-029 (14335-00000-00452) Location: 4692 KENNY ROAD (43220), being 3.77± acres located on the east side of Kenny Road, approximately 430± feet north of Godown Road (010-129789 and 010-129792; Northwest Civic Association). Existing Zoning: M-1, Manufacturing District. Request: L-AR-1, Limited Apartment Residential District. Proposed Use: Multi-unit development. Applicant(s): Preferred Real Estate Investments II, LLC; c/o Jill Tangeman; Vorys, Sater, Seymour and Pease LLP; 52 East Gay Street; Columbus, Ohio 43215. -

14 Christopher Street

14 CHRISTOPHER STREET NYC DIGITAL TAX MAP N BLOCK: 593 LOT: 45 ZONING: R6 ZONING MAP: 12C LPC HISTORIC DISTRICT: GREENWICH VILLAGE SOURCE: NYC DOF 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET PRESENTATION TO THE NEW YORK CITY LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION October 14 2019 MANHATTAN MODERN MANAGEMENT, INC. SMITH & ARCHITECTS AUTHORIZED REPRESENTATIVE ARCHITECT 16 PENN PLAZA, SUITE 511 11-22 44TH ROAD, SUITE 200 NEW YORK, NY 10001 LONG ISLAND CITY, NY 11101 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 1 | 1940 TAX PHOTOGRAPH 2 | 1969 LPC DESIGNATION PHOTOGRAPH 4| 1980 TAX PHOTOGRAPH 5 | 2019 SITE PHOTOGRAPH 3 | 1978 UCRS PHOTOGRAPHS 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET PROJECT LOCATION: DATE: SMITH & ARCHITECTS 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET TIMELINE OF SITE ALTERATIONS - CHRISTOPHER STREET October 14, 2019 2 NEW YORK, NY 10014 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 1 | 1940 TAX PHOTOGRAPH 2 | 1969 LPC DESIGNATION 3 | 1969 LPC DESIGNATION 4 | 2019 SITE PHOTOGRAPH PHOTOGRAPH PHOTOGRAPH PROJECT LOCATION: DATE: SMITH & ARCHITECTS 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET TIMELINE OF SITE ALTERATIONS - GAY STREET October 14, 2019 3 NEW YORK, NY 10014 SCOPE OF WORK: REPLACE 2ND SCOPE OF WORK: LEGALIZE - 5TH FLOOR WINDOWS ON GAY EXISTING 5TH FLOOR WINDOWS ON STREET FACADES AS PER LPC CHRISTOPHER STREET FACADE AS VIOLATION #16/0854 AND LPC PER LPC VIOLATION #16/0854 AND LPC DOCKET #LPC-18-4878. DOCKET #LPC-18-4878 1 | GAY STREET SOUTH FACING FACADE 2 | GAY STREET EAST FACING FACADE 3 | CHRISTOPHER STREET FACADE PROJECT LOCATION: DATE: SMITH & ARCHITECTS 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET EXISTING CONDITIONS PHOTOGRAPHS October 14, 2019 4 NEW YORK, NY 10014 2 3 1 | 4TH AND 5TH STORY WINDOWS 2 | 5TH STORY WINDOW HEAD 3 | 3RD STORY WINDOW 4 | 2ND AND 3RD STORY WINDOWS AND JAMB, TYPICAL SILL AND JAMB, TYPICAL PROJECT LOCATION: DATE: SMITH & ARCHITECTS 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET CHRISTOPHER STREET CLOSE UP PHOTOGRAPHS October 14, 2019 5 NEW YORK, NY 10014 GENERAL NOTES: 1. -

LODGING SUGGESTIONS: Downtown Is 3.5 Miles/Approximately 10 Minutes Away from Our Central Office Location

LODGING SUGGESTIONS: Downtown is 3.5 miles/approximately 10 minutes away from our Central Office location. Hilliard-Rome Road & I70 is 6.5 miles/approximately 10-15 minutes away. The downtown hotels are very nice, but, they can be slightly pricier than other areas. Most of them do offer government rates, however. Both areas offer plenty of restaurants but there is more shopping in the Hilliard-Rome Road & I-70 area. The downtown area hotels that are highlighted are near the Convention Center and Arena District. This area is recommended as there are more restaurant options than in other parts of downtown. DOWNTOWN HOTELS: Arena District Hyatt Regency Holiday Inn Columbus Downtown Capitol 350 North High Street Square Columbus, OH 43215 175 East Town Street 614-463-1234 Columbus, OH 43215 614-221-3281 Courtyard by Marriott Columbus - Downtown 35 West Spring Street The Lofts Hotel Columbus, OH 43215 55 East Nationwide Boulevard 614-228-3200 x190 Columbus, OH 43215 614-461-2658 Crowne Plaza Hotel Columbus Downtown 33 East Nationwide Boulevard Red Roof Inn Columbus Downtown - Columbus, OH 43215 Convention Center 614-461-2667 111 East Nationwide Boulevard Columbus, OH 43215 Double Tree Guest Suites - Columbus 614-224-6539 50 South Front Street Columbus, OH 43215 Renaissance Columbus Downtown Hotel 614-228-4600 50 North Third Street Columbus, OH 43215 Drury Inn & Suites Convention Center 614-228-5050 88 East Nationwide Boulevard Columbus, OH 43215 Residence Inn by Marriott Columbus Downtown 614-221-7008 36 East Gay Street Columbus, OH 43215 Hampton -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX ABC Television Studios 152 Chrysler Building 96, 102 Evelyn Apartments 143–4 Abyssinian Baptist Church 164 Chumley’s 66–8 Fabbri mansion 113 The Alamo 51 Church of the Ascension Fifth Avenue 56, 120, 140 B. Altman Building 96 60–1 Five Points 29–31 American Museum of Natural Church of the Incarnation 95 Flagg, Ernest 43, 55, 156 History 142–3 Church of the Most Precious Flatiron Building 93 The Ansonia 153 Blood 37 Foley Square 19 Apollo Theater 165 Church of St Ann and the Holy Forward Building 23 The Apthorp 144 Trinity 167 42nd Street 98–103 Asia Society 121 Church of St Luke in the Fields Fraunces Tavern 12–13 Astor, John Jacob 50, 55, 100 65 ‘Freedom Tower’ 15 Astor Library 55 Church of San Salvatore 39 Frick Collection 120, 121 Church of the Transfiguration Banca Stabile 37 (Mott Street) 33 Gangs of New York 30 Bayard-Condict Building 54 Church of the Transfiguration Gay Street 69 Beecher, Henry Ward 167, 170, (35th Street) 95 General Motors Building 110 171 City Beautiful movement General Slocum 70, 73, 74 Belvedere Castle 135 58–60 General Theological Seminary Bethesda Terrace 135, 138 City College 161 88–9 Boathouse, Central Park 138 City Hall 18 German American Shooting Bohemian National Hall 116 Colonnade Row 55 Society 72 Borough Hall, Brooklyn 167 Columbia University 158–9 Gilbert, Cass 9, 18, 19, 122 Bow Bridge 138–9 Columbus Circle 149 Gotti, John 40 Bowery 50, 52–4, 57 Columbus Park 29 Grace Court Alley 170 Bowling Green Park 9 Conservatory Water 138 Gracie Mansion 112, 117 Broadway 8, 92 Cooper-Hewitt National Gramercy -

STONEWALL INN, 51-53 Christopher Street, Manhattan Built: 1843 (51), 1846 (53); Combined with New Façade, 1930; Architect, William Bayard Willis

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 23, 2015, Designation List 483 LP-2574 STONEWALL INN, 51-53 Christopher Street, Manhattan Built: 1843 (51), 1846 (53); Combined with New Façade, 1930; architect, William Bayard Willis Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan, Tax Map Block 610, Lot 1 in part consisting of the land on which the buildings at 51-53 Christopher Street are situated On June 23, 2015 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of the Stonewall Inn as a New York City Landmark and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.1). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of the law. Twenty-seven people testified in favor of the designation including Public Advocate Letitia James, Council Member Corey Johnson, Council Member Rosie Mendez, representatives of Comptroller Scott Stringer, Congressman Jerrold Nadler, Assembly Member Deborah Glick, State Senator Brad Hoylman, Manhattan Borough President Gale A. Brewer, Assembly Member Richard N. Gottfried, the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, the Real Estate Board of New York, the Historic Districts Council, the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the Family Equality Council, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the National Parks Conservation Association, SaveStonewall.org, the Society for the Architecture of the City, and Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, New York City, as well as three participants in the Stonewall Rebellion—Martin Boyce, Jim Fouratt, and Dr. Gil Horowitz (Dr. Horowitz represented the Stonewall Veterans Association)—and historians David Carter, Andrew Dolkart, and Ken Lustbader. In an email to the Commission on May 21, 2015 Benjamin Duell, of Duell LLC the owner of 51-53 Christopher Street, expressed his support for the designation. -

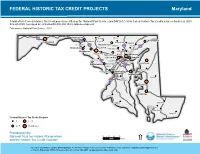

¨§¦81 ¨§¦97 ¨§¦83 ¨§¦70 ¨§¦95 ¨§¦68

FEDERAL HISTORIC TAX CREDIT PROJECTS Maryland A total of 676 Federal Historic Tax Credit projects (certified by the National Park Service) and $441,617,758 in federal Historic Tax Credits between fiscal year 2001 through 2020, leveraged an estimated $2,539,302,108 in total development. Data source: National Park Service, 2020 Hagerstown Thurmont Millers ¨§68 13 3 ¦ Port Deposit 81 Funkstown Keymar 2 Cumberland ¦¨§ 3 Hampstead Monkton Keedysville Westminster §70 Glyndon 83 Bel Air ¦¨ ¦¨§ ¦¨§95 Sharpsburg2 Frederick 3 Reistertown Glen Arm Middletown 18 Stevenson 3 Towson New Market Sykesville Oella Baltimore 2 551 Ellicott City 9 3Dundalk Comus Columbia 195 6 ¦¨§270 ¦¨§ Linthicum 2 Washington Chestertown Gaithersburg 97 Grove ¦¨§ Centreville Silver Spring 3Hyattsville 6 Annapolis ¦¨§495 Upper Denton 295 Marlboro ¦¨§ 12 Easton 7 Cambridge La Plata Chaptico Salisbury Whitehaven Princess Anne Snow Hill Federal Historic Tax Credit Projects 1 6 - 10 2 - 5 11 and over Provided by the National Trust for Historic Preservation 0 510 20 30 and the Historic Tax Credit Coalition Miles R For more information, contact Shaw Sprague, NTHP Vice President for Government Relations | (202) 588-6339 | [email protected] or Patrick Robertson, HTCC Executive Director | (202) 302-2957 | [email protected] Maryland Historic Tax Credit Projects, FY 2001-2020 Project Name Address City Year Qualified Project Use Expenditures Bakery Lofts 43 Lafayette Avenue Annapolis 2015 $611,418 Housing The Wiley H. Bates Junior- 1029 Smithville Street Annapolis 2006 $11,707,557 Multi-Use Senior High School Property No project name 150 Prince George Annapolis 2006 $42,500 Housing Street No project name 123 Main Street Annapolis 2006 $4,701,791 Commercial St. -

$182,000 43 2,455

First Quarter: 2021 Baltimore City Home Sales TOTAL $ SALES YoY 61% 518M 3 YEAR AVG 74% NUMBER MEDIAN AVERAGE DAYS OF SALES SALE PRICE ON MARKET 2,455 $182,000 43 26% 35% -42% YoY YoY YoY 32% 46% -35% 3 YEAR AVG 3 YEAR AVG 3 YEAR AVG FINANCED SALES TOP 10 NEIGHBORHOODS TOP 10 NEIGHBORHOODS BY NUMBER OF SALES BY AVERAGE PRICE 27% 1. Canton 1. Guilford YoY 2. Riverside 2. North Roland Park/Poplar Hill 32% 3. Belair-Edison 3. Inner Harbor 66% 3 YEAR AVG 4. Hampden 4. Spring Garden Industrial Area 5. Patterson Park Neighborhood 5. Roland Park STANDARD SALES* 6. Pigtown 6. Homeland 7. South Baltimore 7. The Orchards 20% YoY 8. Locust Point 8. Bolton Hill 15% 9. Greektown 9. Bellona-Gittings 3 YEAR AVG 85% 10. Glenham-Belhar 10. Wyndhurst *Standard sales exclude the following MLS “sale type” categories: Auction, Bankruptcy Property, In Foreclosure, Notice of Default, HUD Owned, Probate Listing, REO (Real Estate Owned), Short Sale, Third Party Approval, Undisclosed. Party Approval, Listing, REO (Real Estate Owned), Short Sale, Third Notice of Default, HUD Owned, Probate In Foreclosure, sales exclude the following MLS “sale type” categories: Auction, Bankruptcy Property, *Standard Source: BrightMLS, Analysis by Live Baltimore First Quarter: 2021 Baltimore City Home Sales $105M TOTAL $195M $115M TOTAL TOTAL 261 SALES YoY $365K MEDIAN YoY 63 DOM YoY CEDARCROFT MT PLEASANT THE ORCHARDS BELLONA- LAKE WALKER IDLEWOOD PARK TAYLOR HEIGHTS GITTINGS GLEN OAKS CHESWOLDE NORTH ROLAND PARK/ NORTH HARFORD ROAD YoY CROSS COUNTRY POPLAR HILL LAKE EVESHAM EVESHAM -

City of Longmont Historic Properties (May 2021)

City of Longmont Historic Properties (May 2021) Contributing NOT Within Building Original Plat Local National (National of Property Address Landmark Landmark District) Notes Longmont 1000 Block Fourth Avenue Yes WEST 1005 Third Avenue Yes WEST 1007 Third Avenue WEST 1009 Third Avenue WEST 1010 Third Avenue WEST 1011 Fourth Avenue WEST 1011 Third Avenue WEST 1012 Third Avenue WEST 1013 Fourth Avenue WEST 1017 Fourth Avenue WEST 1019 Third Avenue Yes WEST 102 Fourth Avenue Yes 1021 Third Avenue Yes WEST 1022 Third Avenue WEST 1025 Third Avenue WEST 1027 Fourth Avenue WEST 103 Main Street Yes 1032 Collyer Street Yes X 10662 Pike Road Yes X 1102 Third Avenue WEST 1106 Third Avenue WEST 1110 Fourth Avenue WEST 1110 Longs Peak Avenue Yes 1111 Fourth Avenue WEST 1114 Fourth Avenue WEST 1117 Neon Forest Circle Yes X 1117 Third Avenue Yes 1120 Third Avenue WEST 1121 Third Avenue WEST 1125 Third Avenue WEST 1126 Fourth Avenue WEST 1126 Third Avenue WEST 1127 17th Avenue YES X 1128 Fourth Avenue WEST 1130 Collyer Street Yes X 1203 Third Avenue WEST X 1206 Third Avenue Yes WEST X 1210 Third Avenue WEST X 1211 Third Avenue WEST X 1225 Third Avenue WEST X 1228 Third Avenue WEST X 1230 Third Avenue WEST X 1236 Third Avenue Yes WEST X 1237 Third Avenue Yes WEST X 1239 Third Avenue WEST X 1241 Third Avenue WEST X 1244 Third Avenue WEST X 1246 Third Avenue WEST X 1249 Third Avenue Yes WEST X 1255 Third Avenue WEST X 1266 Longs Peak Avenue Yes X 1283 Third Avenue Yes X Entire X Property is a National Entire 1303 Hover Street Yes District Property 13076 Pike Road Yes X 1309 Hover Street Yes X 136 S. -

The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections

Guide to the Geographic File ca 1800-present (Bulk 1850-1950) PR20 The New-York Historical Society 170 Central Park West New York, NY 10024 Descriptive Summary Title: Geographic File Dates: ca 1800-present (bulk 1850-1950) Abstract: The Geographic File includes prints, photographs, and newspaper clippings of street views and buildings in the five boroughs (Series III and IV), arranged by location or by type of structure. Series I and II contain foreign views and United States views outside of New York City. Quantity: 135 linear feet (160 boxes; 124 drawers of flat files) Call Phrase: PR 20 Note: This is a PDF version of a legacy finding aid that has not been updated recently and is provided “as is.” It is key-word searchable and can be used to identify and request materials through our online request system (AEON). PR 000 2 The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections PR 020 GEOGRAPHIC FILE Series I. Foreign Views Series II. American Views Series III. New York City Views (Manhattan) Series IV. New York City Views (Other Boroughs) Processed by Committee Current as of May 25, 2006 PR 020 3 Provenance Material is a combination of gifts and purchases. Individual dates or information can be found on the verso of most items. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers. Portions of the collection that have been photocopied or microfilmed will be brought to the researcher in that format; microfilm can be made available through Interlibrary Loan. Photocopying Photocopying will be undertaken by staff only, and is limited to twenty exposures of stable, unbound material per day. -

Greenwich Village: 8Th Street Corridor

Real estate investment services MetroGrid Report: Greenwich Village: 8th Street Corridor FOCUS ON NYC SUBMARKETS SEPTEMBER 2015 A Start-Up Friendly Corridor Where Retailers Can Find Value With average asking retail rents rising to $3,683 per square foot Avenue is one of those places. Known as the Main Street of in Midtown, to $1,700 per square foot on the Eastside, and to Greenwich Village, Eighth Street is a demographic gold mine $977 per square foot in Soho, it would appear that the island of that blends the new and old and includes a large dose of art, Manhattan is no place for a new retailer to venture. music, and cultural history. But that’s not the case. Manhattan contains plenty of hidden The first Whitney Museum opened in 1831 at 8 W Eighth Street; treasures where an entrepreneur can launch a new retail busi- Bob Dylan met Allen Ginsberg at a party at the Eighth Street ness in spaces leasing for under $150 per square foot. Book Shop, now Stumptown Coffee Roasters at MacDougal Greenwich Village’s Eighth Street between Broadway and Sixth Street; and at 52 Eighth Street Jimi Hendrix opened Electric Lady Studios, which is still recording hits. MetroGrid Report: Greenwich Village FOCUS ON NYC SUBMARKETS Real estate investment services Unique mom-and-pop storefronts populate Eighth Street where At 5 W Eighth Street, the Marlton Hotel, which was built in 1900 asking rents are averaging $143 per square foot. and became a bohemian hangout in the mid-20th Century, was converted from an SRO and reopened in 2013 as a Parisian-in- Opportunities for retailers abound on Eighth Street, according spired 107-room boutique hotel. -

Greenwich Village Literary Tour

c567446 Ch05.qxd 2/18/03 9:02 AM Page 68 • Walking Tour 5 • Greenwich Village Literary Tour Start: Bleecker Street between La Guardia Place and Thompson Street. Subway: Take the 6 to Bleecker Street, which lets you out at Bleecker and Lafayette streets. Walk west on Bleecker. Finish: 14 West 10th St. Time: Approximately 4 to 5 hours. Best Time: If you plan to do the whole tour, start fairly early in the day (there’s a breakfast break near the start). The Village has always attracted rebels, radicals, and creative types, from earnest 18th- century revolutionary Thomas Paine, to early-20th-century radicals such as John Reed and Mabel Dodge, to the Stonewall rioters who gave birth to the gay liberation movement in 1969. A Village protest in 1817 saved the area’s colorfully convoluted 68 c567446 Ch05.qxd 2/18/03 9:02 AM Page 69 Greenwich Village Literary Tour • 69 lanes and byways when the city imposed a geometric grid sys- tem on the rest of New York’s streets. Much of Village life cen- ters around Washington Square Park, the site of hippie rallies and counterculture demonstrations, and the former stomping ground of Henry James and Edith Wharton. Many other American writers have at some time made their homes in the Village. As early as the 19th century, it was New York’s literary hub and a hot spot for salons and other intellectual gatherings. Both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art came into being here, albeit some 60 years apart. -

14 Christopher Street

14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 1 | LPC HISTORIC DISTRICT MAP: GREENWICH 2 I NYC DIGITAL TAX MAP N VILLAGE BLOCK: 593 LOT: 45 SOURCE: NYC LPC ZONING: R6 ZONING MAP: 12C SOURCE: NYC DOF 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET PRESENTATION TO THE NEW YORK CITY LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION October 29, 2019 MANHATTAN MODERN MANAGEMENT, INC. SMITH & ARCHITECTS AUTHORIZED REPRESENTATIVE ARCHITECT 16 PENN PLAZA, SUITE 511 11-22 44TH ROAD, SUITE 200 NEW YORK, NY 10001 LONG ISLAND CITY, NY 11101 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 1 | 1940 TAX PHOTOGRAPH 2 | 1969 LPC DESIGNATION PHOTOGRAPH 4| 1980 TAX PHOTOGRAPH 5 | 2019 SITE PHOTOGRAPH 3 | 1978 UCRS PHOTOGRAPHS 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET PROJECT LOCATION: DATE: SMITH & ARCHITECTS 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET TIMELINE OF SITE ALTERATIONS - CHRISTOPHER STREET October 25, 2019 2 NEW YORK, NY 10014 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET 1 | 1940 TAX PHOTOGRAPH 2 | 1969 LPC DESIGNATION 3 | 1969 LPC DESIGNATION 4 | 2019 SITE PHOTOGRAPH PHOTOGRAPH PHOTOGRAPH PROJECT LOCATION: DATE: SMITH & ARCHITECTS 14 CHRISTOPHER STREET TIMELINE OF SITE ALTERATIONS - GAY STREET October 25, 2019 3 NEW YORK, NY 10014 SCOPE OF WORK: REPLACE SCOPE OF WORK: LEGALIZE 2ND - 5TH FLOOR WINDOWS ON EXISTING 5TH FLOOR WINDOWS ON GAY STREET FACADES AS PER CHRISTOPHER STREET FACADE AS LPC VIOLATION #16/0854 AND LPC PER LPC VIOLATION #16/0854 AND LPC DOCKET #LPC-20-02636. DOCKET #LPC-20-02636 1 | GAY STREET SOUTH FACING FACADE 2 | GAY STREET EAST FACING FACADE 3 | CHRISTOPHER STREET FACADE LPC VIOLATION #17/0055: MODIFICATION OF LARGE MASONRY OPENING WITH EXPANSES OF GLAZING STOREFRONT TRANSOM WINDOW AND INSTALLATION OF & FULL-WIDTH METAL BALCONIES, GRANDFATHERED HVAC UNITS AT GROUND FLOOR OF GAY STREET FACADE FROM 1978 UCRS PHOTOGRPAHS.