Suicide Research: Selected Readings Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Levomilnacipran for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder

Out of the Pipeline Levomilnacipran for the treatment of major depressive disorder Matthew Macaluso, DO, Hala Kazanchi, MD, and Vikram Malhotra, MD An SNRI with n July 2013, the FDA approved levomil- Table 1 once-daily dosing, nacipran for the treatment of major de- Levomilnacipran: Fast facts levomilnacipran pressive disorder (MDD) in adults.1 It is I Brand name: Fetzima decreased core available in a once-daily, extended-release formulation (Table 1).1 The drug is the fifth Class: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake symptoms of inhibitor serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibi- MDD and was well Indication: Treatment of major depressive tor (SNRI) to be sold in the United States disorder in adults tolerated in clinical and the fourth to receive FDA approval for FDA approval date: July 26, 2013 trials treating MDD. Availability date: Fourth quarter of 2013 Levomilnacipran is believed to be the Manufacturer: Forest Pharmaceuticals more active enantiomer of milnacipran, Dosage forms: Extended–release capsules in which has been available in Europe for 20 mg, 40 mg, 80 mg, and 120 mg strengths years and was approved by the FDA in Recommended dosage: 40 mg to 120 mg 2009 for treating fibromyalgia. Efficacy of capsule once daily with or without food levomilnacipran for treating patients with Source: Reference 1 MDD was established in three 8-week ran- domized controlled trials (RCTs).1 cial and occupational functioning in addi- Clinical implications tion to improvement in the core symptoms Levomilnacipran is indicated for treating of depression.5 -

Milnacipran Remediates Impulsive Deficits in Rats with Lesions of the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex

Title Milnacipran Remediates Impulsive Deficits in Rats with Lesions of the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Author(s) Tsutsui-Kimura, Iku; Yoshida, Takayuki; Ohmura, Yu; Izumi, Takeshi; Yoshioka, Mitsuhiro International journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 18(5), pyu083 Citation https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyu083 Issue Date 2015-03 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/59283 Rights(URL) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 Type article File Information pyu083.full.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 2015, 1–14 doi:10.1093/ijnp/pyu083 Research Article research article Milnacipran Remediates Impulsive Deficits in Rats with Lesions of the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex Iku Tsutsui-Kimura, PhD; Takayuki Yoshida, PhD; Yu Ohmura, PhD; Takeshi Izumi, MD, PhD; Mitsuhiro Yoshioka, MD, PhD Department of Neuropharmacology, Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine, Sapporo, Japan (Drs Tsutsui-Kimura, Yoshida, Ohmura, Izumi, and Yoshioka); Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, Japan (Dr Tsutsui-Kimura); Department of Neuropsychiatry, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan (Dr Tsutsui-Kimura). Correspondence: Yu Ohmura, PhD, Department of Neuropharmacology, Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine, N15 W7, Kita-ku, Sapporo, 060-8638, Japan ([email protected]). Abstract Background: Deficits in impulse control are often observed in psychiatric disorders in which abnormalities of the prefrontal cortex are observed, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder. We recently found that milnacipran, a serotonin/noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, could suppress impulsive action in normal rats. However, whether milnacipran could suppress elevated impulsive action in rats with lesions of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which is functionally comparable with the human prefrontal cortex, remains unknown. -

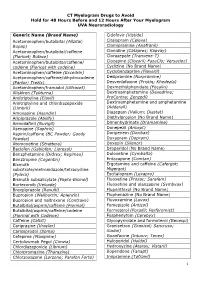

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology

CT Myelogram Drugs to Avoid Hold for 48 Hours Before and 12 Hours After Your Myelogram UVA Neuroradiology Generic Name (Brand Name) Cidofovir (Vistide) Acetaminophen/butalbital (Allzital; Citalopram (Celexa) Bupap) Clomipramine (Anafranil) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine Clonidine (Catapres; Kapvay) (Fioricet; Butace) Clorazepate (Tranxene-T) Acetaminophen/butalbital/caffeine/ Clozapine (Clozaril; FazaClo; Versacloz) codeine (Fioricet with codeine) Cyclizine (No Brand Name) Acetaminophen/caffeine (Excedrin) Cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) Acetaminophen/caffeine/dihydrocodeine Desipramine (Norpramine) (Panlor; Trezix) Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq; Khedezla) Acetaminophen/tramadol (Ultracet) Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) Aliskiren (Tekturna) Dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine; Amitriptyline (Elavil) ProCentra; Zenzedi) Amitriptyline and chlordiazepoxide Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine (Limbril) (Adderall) Amoxapine (Asendin) Diazepam (Valium; Diastat) Aripiprazole (Abilify) Diethylpropion (No Brand Name) Armodafinil (Nuvigil) Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) Asenapine (Saphris) Donepezil (Aricept) Aspirin/caffeine (BC Powder; Goody Doripenem (Doribax) Powder) Doxapram (Dopram) Atomoxetine (Strattera) Doxepin (Silenor) Baclofen (Gablofen; Lioresal) Droperidol (No Brand Name) Benzphetamine (Didrex; Regimex) Duloxetine (Cymbalta) Benztropine (Cogentin) Entacapone (Comtan) Bismuth Ergotamine and caffeine (Cafergot; subcitrate/metronidazole/tetracycline Migergot) (Pylera) Escitalopram (Lexapro) Bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) Fluoxetine (Prozac; Sarafem) -

Milnacipran for Pain in Fibromyalgia in Adults

Milnacipran for pain in fibromyalgia in adults (Review) Cording M, Derry S, Phillips T, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ This is a reprint of a Cochrane review, prepared and maintained by The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 10 http://www.thecochranelibrary.com Milnacipran for pain in fibromyalgia in adults (Review) Copyright © 2015 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 4 BACKGROUND .................................... 6 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 7 METHODS ...................................... 7 RESULTS....................................... 9 Figure1. ..................................... 10 Figure2. ..................................... 12 Figure3. ..................................... 13 Figure4. ..................................... 14 Figure5. ..................................... 18 DISCUSSION ..................................... 21 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 22 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 23 REFERENCES ..................................... 23 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 27 DATAANDANALYSES. 38 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Milnacipran 100 mg/day versus placebo, Outcome 1 At least 30% pain relief. 39 Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Milnacipran 100 mg/day versus placebo, Outcome 2 PGIC ’much improved’ or ’very much improved’.................................... 40 Analysis 1.3. Comparison -

Efficacy of Milnacipran in Patients with Fibromyalgia R

Efficacy of Milnacipran in Patients with Fibromyalgia R. MICHAEL GENDREAU, MICHAEL D. THORN, JUDY F. GENDREAU, JAY D. KRANZLER, SAULO RIBEIRO, RICHARD H. GRACELY, DAVID A. WILLIAMS, PHILIP J. MEASE, SAMUEL A. McLEAN, and DANIEL J. CLAUW ABSTRACT. Objective. Fibromyalgia (FM) is a common musculoskeletal condition characterized by widespread pain, tenderness, and a variety of other somatic symptoms. Current treatments are modestly effec- tive. Arguably, the best studied and most effective compounds are tricyclic antidepressants (TCA). Milnacipran, a nontricyclic compound that inhibits the reuptake of both serotonin and norepineph- rine, may provide many of the beneficial effects of TCA with a superior side effect profile. Methods. One hundred twenty-five patients with FM were randomly assigned in a 3:3:2 ratio to receive milnacipran twice daily, milnacipran once daily, or placebo for 3 months in a double-blind dose-escalation trial; 92% of twice-daily and 81% of once-daily participants achieved dose escala- tion to the target milnacipran dose of 200 mg. Results. The primary endpoint was reduction of pain. Both the once- and twice-daily groups showed statistically significant improvements in pain, as well as improvements in global well being, fatigue, and other domains. Response rates for patients receiving milnacipran were equal in patients with and without comorbid depression, but placebo response rates were considerably higher in depressed patients, leading to significantly greater overall efficacy in the nondepressed group. Conclusion. In this Phase II study, milnacipran led to statistically significant improvements in pain and other symptoms of FM. The effect sizes were equal to those previously found with TCA, and the drug was generally well tolerated. -

View Rome, Italy Final Program

8TH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF PARKINSON’S DISEASE AND MOVEMENT DISORDERS CONGRESS OF PARKINSON’S DISEASE 8TH INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS Invitation . .2 Acknowledgements . .4 Organization . .5 MDS Committees and Task Forces . .8 International Congress Registration and Venue . 11 International Congress Information . .12 Continuing Medical Education . .12 Evaluations . .12 Press Room . .13 Social Events . .14 Program at a Glance . .17 Scientific Sessions . .18 Faculty . .38 Committee and Task Force Meetings . .41 Exhibitor Information and Directory . .42 Floor Plan and Meeting Space . .46 Map of Rome . .51 Poster Session 1 . .52 Poster Session 2 . .63 Poster Session 3 . .73 Poster Session 4 . .83 THE CONGRESS IS UNDER THE AUSPICES OF: The President of the Italian Republic The Prime Minister of the Italian government The National Institute of Health (ISS) The National Research Council (CNR) The City of Rome The School of Medicine and Surgery, University of Rome “La Sapienza” The Italian Society of Neurology 1 THE MOVEMENT DISORDER SOCIETY INVITATION Dear Colleagues, Rome, Italy On behalf of the Officers and International Executive Committee of The Movement Disorder Society, welcome to the 8th International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. I would like to thank the faculty and the members of the Congress Scientific Program Committee for this exemplary scientific program and for their contribution to the International Congress. The International Congress week begins with a variety of Kickoff Seminars, which are supported through unrestricted educational grants from industry. The week continues with a wide array of plenary sessions, parallel sessions, seminars and video dinners. Poster sessions are unopposed and, to further serve our participants, time has also been allotted for 16 poster platform presentations. -

Anticonvulsants Antipsychotics Benzodiazepines/Anxiolytics ADHD

Anticonvulsants Antidepressants Generic Name Brand Name Generic Name Brand Name Carbamazepine Tegretol SSRI Divalproex Depakote Citalopram Celexa Lamotrigine Lamictal Escitalopram Lexapro Topirimate Topamax Fluoxetine Prozac Fluvoxamine Luvox Paroxetine Paxil Antipsychotics Sertraline Zoloft Generic Name Brand Name SNRI Typical Desvenlafaxine Pristiq Chlorpromazine Thorazine Duloextine Cymbalta Fluphenazine Prolixin Milnacipran Savella Haloperidol Haldol Venlafaxine Effexor Perphenazine Trilafon SARI Atypical Nefazodone Serzone Aripiprazole Abilify Trazodone Desyrel Clozapine Clozaril TCA Lurasidone Latuda Clomimpramine Enafranil Olanzapine Zyprexa Despiramine Norpramin Quetiapine Seroquel Nortriptyline Pamelor Risperidone Risperal MAOI Ziprasidone Geodon Phenylzine Nardil Selegiline Emsam Tranylcypromine Parnate Benzodiazepines/Anxiolytics DNRI Generic Name Brand Name Bupropion Wellbutrin Alprazolam Xanax Clonazepam Klonopin Sedative‐Hypnotics Lorazepam Ativan Generic Name Brand Name Diazepam Valium Clonidine Kapvay Buspirone Buspar Eszopiclone Lunesta Pentobarbital Nembutal Phenobarbital Luminal ADHD Medicines Zaleplon Sonata Generic Name Brand Name Zolpidem Ambien Stimulant Amphetamine Adderall Others Dexmethylphenidate Focalin Generic Name Brand Name Dextroamphetamine Dexedrine Antihistamine Methylphenidate Ritalin Non‐stimulant Diphenhydramine Bendryl Atomoxetine Strattera Anti‐tremor Guanfacine Intuniv Benztropine Cogentin Mood stabilizer (bipolar treatment) Lithium Lithane Never Mix, Never Worry: What Clinicians Need to Know about -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0202317 A1 Rau Et Al

US 20150202317A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0202317 A1 Rau et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jul. 23, 2015 (54) DIPEPTDE-BASED PRODRUG LINKERS Publication Classification FOR ALPHATIC AMNE-CONTAINING DRUGS (51) Int. Cl. A647/48 (2006.01) (71) Applicant: Ascendis Pharma A/S, Hellerup (DK) A638/26 (2006.01) A6M5/9 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Harald Rau, Heidelberg (DE); Torben A 6LX3/553 (2006.01) Le?mann, Neustadt an der Weinstrasse (52) U.S. Cl. (DE) CPC ......... A61K 47/48338 (2013.01); A61 K3I/553 (2013.01); A61 K38/26 (2013.01); A61 K (21) Appl. No.: 14/674,928 47/48215 (2013.01); A61M 5/19 (2013.01) (22) Filed: Mar. 31, 2015 (57) ABSTRACT The present invention relates to a prodrug or a pharmaceuti Related U.S. Application Data cally acceptable salt thereof, comprising a drug linker conju (63) Continuation of application No. 13/574,092, filed on gate D-L, wherein D being a biologically active moiety con Oct. 15, 2012, filed as application No. PCT/EP2011/ taining an aliphatic amine group is conjugated to one or more 050821 on Jan. 21, 2011. polymeric carriers via dipeptide-containing linkers L. Such carrier-linked prodrugs achieve drug releases with therapeu (30) Foreign Application Priority Data tically useful half-lives. The invention also relates to pharma ceutical compositions comprising said prodrugs and their use Jan. 22, 2010 (EP) ................................ 10 151564.1 as medicaments. US 2015/0202317 A1 Jul. 23, 2015 DIPEPTDE-BASED PRODRUG LINKERS 0007 Alternatively, the drugs may be conjugated to a car FOR ALPHATIC AMNE-CONTAINING rier through permanent covalent bonds. -

Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of Gutlbrain Interaction): a Rome Foundation Working Team Report Douglas A

Gastroenterology 2018;154:1140–1171 SPECIAL REPORT Neuromodulators for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Disorders of GutLBrain Interaction): A Rome Foundation Working Team Report Douglas A. Drossman,1,2 Jan Tack,3 Alexander C. Ford,4,5 Eva Szigethy,6 Hans Törnblom,7 and Lukas Van Oudenhove8 1Center for Functional Gastrointestinal and Motility Disorders, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; 2Center for Education and Practice of Biopsychosocial Care and Drossman Gastroenterology, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; 3Translational Research Center for Gastrointestinal Disorders, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; 4Leeds Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom; 5Leeds Gastroenterology Institute, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds, United Kingdom; 6Departments of Psychiatry and Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; 7Departments of Internal Medicine and Clinical Nutrition, Institute of Medicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden; and 8Laboratory for BrainÀGut Axis Studies, Translational Research Center for Gastrointestinal Disorders, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium BACKGROUND & AIMS: Central neuromodulators (antide- summary information and guidelines for the use of central pressants, antipsychotics, and other central nervous neuromodulators in the treatment of chronic gastrointestinal systemÀtargeted medications) are increasingly used for treat- symptoms and FGIDs. Further studies are needed to confirm ment -

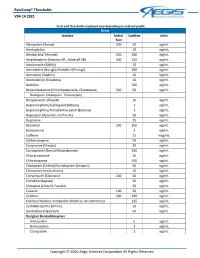

Paincomp® Thresholds V04.14.2021 Copyright © 2020 Aegis Sciences

PainComp® Thresholds V04.14.2021 Tests and thresholds employed vary depending on ordered profile Urine Analyte Initial Confirm Units Test Alprazolam (Xanax) 200 50 ng/mL Amitriptyline 10 ng/mL Amobarbital (Amytal) 200 200 ng/mL Amphetamine (Adzenys ER , Adderall XR) 500 250 ng/mL Aripiprazole (Abilify) 10 ng/mL Armodafinil (Nuvigil)/Modafinil (Provigil) 100 ng/mL Asenapine (Saphris) 10 ng/mL Atomoxetine (Strattera) 10 ng/mL Baclofen 500 ng/mL Benzodiazepines (Chlordiazepoxide, Clorazepate, 200 50 ng/mL Diazepam, Oxazepam, Temazepam) Brexpiprazole (Rexulti) 10 ng/mL Buprenorphine/Sublingual (Belbuca) 1 ng/mL Buprenorphine/Transdermal patch (Butrans) 1 ng/mL Bupropion (Aplenzin, Forfivo XL) 50 ng/mL Buspirone 25 ng/mL Butalbital 200 200 ng/mL Butorphanol 1 ng/mL Caffeine 15 mcg/mL Carbamazepine 50 ng/mL Cariprazine (Vraylar) 20 ng/mL Carisoprodol (Soma)/Meprobamate 200 ng/mL Chlorpromazine 10 ng/mL Chlorzoxazone 500 ng/mL Citalopram (Celexa)/Escitalopram (Lexapro) 50 ng/mL Clomipramine (Anafranil) 10 ng/mL Clonazepam (Klonopin) 200 50 ng/mL Clonidine (Kapvay) 50 ng/mL Clozapine (Clozaril, Fazaclo) 50 ng/mL Cocaine 100 50 ng/mL Codeine 200 100 ng/mL Cotinine/Nicotine metabolite (Habitrol, Nicoderm CQ) 125 ng/mL Cyclobenzaprine (Amrix) 10 ng/mL Dantrolene (Dantrium) 50 ng/mL Designer Benzodiazepines Adinazolam 5 ng/mL Bromazolam 1 ng/mL Clonazolam 1 ng/mL Copyright © 2020 Aegis Sciences Corporation All Rights Reserved PainComp® Thresholds V04.14.2021 Deschloroetizolam 1 ng/mL Diclazepam 1 ng/mL Etizolam 1 ng/mL Flualprazolam 1 ng/mL Flubromazepam -

Effects of Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors on Locomotion and Prefrontal Monoamine Release in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats

Effects of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors on locomotion and prefrontal monoamine release in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Umehara M, Ago Y, Fujita K, Hiramatsu N, Takuma K, Matsuda T. Laboratory of Medicinal Pharmacology, Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Osaka University, 1-6 Yamada-oka, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013 Jan 30. pii: S0014-2999(13)00048-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.01.033. [Epub ahead of print] Catecholamine neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex plays a key role in the therapeutic actions of drugs for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Recent clinical studies show that several serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors have potential for treating ADHD. In this study, we examined the effects of acute treatment with serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors on locomotion and the extracellular levels of monoamines in the prefrontal cortex in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR), an animal model of ADHD. Adolescent male SHR exhibited greater horizontal locomotion in an open-field test than male WKY control rats. Psychostimulant methylphenidate (0.3 and 1mg/kg), the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine (1 and 3mg/kg), and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors duloxetine (10mg/kg), venlafaxine (10 and 30mg/kg) and milnacipran (30mg/kg) reduced the horizontal activity in SHR, but did not affect in WKY rats. The selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor reboxetine (10mg/kg) and the tricyclic antidepressant desipramine (10 and 30mg/kg) also reduced the horizontal activity in SHR, whereas the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram (30mg/kg) did not. Microdialysis studies showed that atomoxetine, methylphenidate, duloxetine, venlafaxine, milnacipran, and reboxetine increased the extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in the prefrontal cortex in SHR. -

Milnacipran, a Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor: a Novel Treatment for Fibromyalgia

Drug Evaluation Milnacipran, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor: a novel treatment for fibromyalgia Milnacipran hydrochloride is a serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE) reuptake inhibitor that was recently approved by the US FDA for the treatment of fibromyalgia (FM). Evidence has accumulated suggesting that, in animal models, milnacipran may exert pain-mitigating influences involving norepinephrine- and serotonin-related processes at supraspinal, spinal and peripheral levels in pain transmission. Milnacipran has demonstrated efficacy for the reduction of pain as well as improvements in global assessments of well-being and functional capacity among treated FM patients. Its role in addressing comorbidities associated with FM, including visceral pain and migraine, has, as yet, to be investigated. Milnacipran may be of special interest for use in patients for whom hepatic dysfunction precludes the use of other agents, for example, duloxetine. It has a negligible influence on cytochrome metabolism, and therefore may be of particular benefit in patients requiring multiple concurrently prescribed medications. Milnacipran may comprise a reasonable option in the armamentarium of treatments available to manage FM. KEYWORDS: antidepressants n chronic pain n fibromyalgian milnacipran n serotonin Raphael J Leo and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine and Fibromyalgia (FM) is a syndrome characterized Several pharmacological approaches have Biomedical Sciences, by chronic, widespread musculoskeletal pain and been advocated for the treatment of FM. State University of New York at tenderness. The prevalence of FM in the general Because of their impact on these presump- Buffalo, Erie County Medical population is estimated to be 2–4%; it tends to tive pathophysiologic processes, antidepres- Center, 462 Grider Street, show a female predilection, and increases with sants have frequently been advocated for Buffalo, NY 14215, USA age [1,2].