Financial Counseling and Access for the Financially Vulnerable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

For 30 Minutes, James H. Howard Single-Handedly Fought Off Marauding German Fighters to Defend the B-17S of 401St Bomb Group. for That, He Received the Medal of Honor

For 30 minutes, James H. Howard single-handedly fought off marauding German fighters to defend the B-17s of 401st Bomb Group. For that, he received the Medal of Honor. One-Man Air Force By Rebecca Grant Mustang pilot who took on the German Air Force single-handedly, and saved on Nazi aircraft and fuel production. our 401st Bomb Group from disaster?” uesday, Jan. 11, 1944, was Devastating missions to targets such wondered Col. Harold Bowman, the a rough day for the B-17Gs as Ploesti in Romania had already unit’s commander. of the 401st Bomb Group. produced Medal of Honor recipients. Soon the bomber pilots knew—and TIt was their 14th mission, but the Many were awarded posthumously, and so did those back home. first one on which they took heavy nearly all went to bomber crewmen. “Maj. James H. Howard was identi- losses—four aircraft missing in ac- Waist gunners, pilots, and naviga- fied today as the lone United States tion after bombing Me 110 fighter tors—all were carrying out heroic acts fighter pilot who for more than 30 production plants at Oschersleben and in the face of the enemy. minutes fought off about 30 Ger- Halberstadt, Germany. The lone P-51 pilot on this bomb- man fighters trying to attack Eighth Turning for home, they witnessed ing run would, in fact, become the Air Force B-17 formations returning an amazing sight: A single P-51 stayed only fighter pilot awarded the Medal from Oschersleben and Halberstadt with them for an incredible 30 minutes of Honor in World War II’s European in Germany,” reported the New York on egress, chasing off German fighters Theater. -

US, JAPANESE, and UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, and the CONSTRUCTION of TEEN IDENTITY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by British Columbia's network of post-secondary digital repositories BLOCKING THE SCHOOL PLAY: US, JAPANESE, AND UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF TEEN IDENTITY by Jennifer Bomford B.A., University of Northern British Columbia, 1999 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2016 © Jennifer Bomford, 2016 ABSTRACT School spaces differ regionally and internationally, and this difference can be seen in television programmes featuring high schools. As television must always create its spaces and places on the screen, what, then, is the significance of the varying emphases as well as the commonalities constructed in televisual high school settings in UK, US, and Japanese television shows? This master’s thesis considers how fictional televisual high schools both contest and construct national identity. In order to do this, it posits the existence of the televisual school story, a descendant of the literary school story. It then compares the formal and narrative ways in which Glee (2009-2015), Hex (2004-2005), and Ouran koukou hosutobu (2006) deploy space and place to create identity on the screen. In particular, it examines how heteronormativity and gender roles affect the abilities of characters to move through spaces, across boundaries, and gain secure places of their own. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgement v Introduction Orientation 1 Space and Place in Schools 5 Schools on TV 11 Schools on TV from Japan, 12 the U.S., and the U.K. -

Easy Access Rules for Medical Requirements

Easy Access Rules for Medical Requirements EASA eRules: aviation rules for the 21st century Rules and regulations are the core of the European Union civil aviation system. The aim of the EASA eRules project is to make them accessible in an efficient and reliable way to stakeholders. EASA eRules will be a comprehensive, single system for the drafting, sharing and storing of rules. It will be the single source for all aviation safety rules applicable to European airspace users. It will offer easy (online) access to all rules and regulations as well as new and innovative applications such as rulemaking process automation, stakeholder consultation, cross-referencing, and comparison with ICAO and third countries’ standards. To achieve these ambitious objectives, the EASA eRules project is structured in ten modules to cover all aviation rules and innovative functionalities. The EASA eRules system is developed and implemented in close cooperation with Member States and aviation industry to ensure that all its capabilities are relevant and effective. Published June 20201 Copyright notice © European Union, 1998-2020 Except where otherwise stated, reuse of the EUR-Lex data for commercial or non-commercial purposes is authorised provided the source is acknowledged ('© European Union, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/, 1998-2020') 2. 1 The published date represents the date when the consolidated version of the document was generated. 2 Euro-Lex, Important Legal Notice: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/content/legal-notice/legal-notice.html. Powered by EASA eRules Page 2 of 274| Jun 2020 Easy Access Rules for Medical Disclaimer Requirements DISCLAIMER This version is issued by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) in order to provide its stakeholders with an updated, consolidated, and easy-to-read publication. -

Steakhouse Live

Critical Interup tions Vol 1 Steakhouse Live EDITED BY CRITICAL INTERRUPTIONS WITH PALIN ANSUSINHA, KATY BAIRD, KATHARINA JOY BOOK, JENNIFER BOYD, JASMINE SHIGEMURA LEE, EMMA SELWYN AND MARIKISCRYCRYCRY (MALIK NASHAD SHARPE) Critical interruptions Vol 1: Steakhouse Live By Critical Interruptions (Diana Damian Martin and Bojana Janković) [criticalinterruptions.com] with Palin Ansusinha, Katy Baird, Katharina Joy Book, Jennifer Boyd, Jasmine Shigemura Lee, Emma Selwyn and Marikiscrycrycry (Malik Nashad Sharpe) Designed by Gareth Damian Martin Images by Julia Bauer and Manuel Vason Printed by Book Printers UK Copyright © Critical Interruptions and the contributors 2018 Supported by Live Art UK and Steakhouse Live Live Art UK is supported by Arts Council England through the Live Art Development Agency’s National Portfolio Organisation funding. The Steakhouse: Live Writing project was supported through Steakhouse Live Festival 2016 funded by Arts Council England. To the community of criticism: those who make, write, curate, support, sustain, activate, agitate and labour in and around Live Art. 4 Over the last twenty years, the ecologies of critical practice under- went fundamental shifts. Criticism moved online; it moved away from full-time jobs; it moved into venues, inhabited festivals, be- came embedded. Yet, for all the changes, no dent was made in the structures underpinning the practice. Blogs broke the word count constraints of broadsheets but often continued awarding stars. On- line publications created space for more writers, many of whom were women, but most of whom were still white, British and middle class. Meanwhile, no one was getting paid; most lived in London; every- one still wanted the press ticket for the mainstream, not the radical. -

Evaluation of Medicaid Medical Homes for Pregnant Women in Southeast Wisconsin

Evaluation of Medicaid Medical Homes for Pregnant Women in Southeast Wisconsin Final Report Submitted to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services Revised March 2016 Donna Friedsam, MPH, Researcher and Project Manager Lindsey Leininger, PhD, Principal Investigator Kristen Voskuil, MA, Associate Researcher UW Population Health Institute DHS Medicaid OB Medical Home Evaluation Executive Summary This study evaluates a pilot program, launched by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS) in January 2011, which enrolls high-risk pregnant women in Southeast Wisconsin into a medical home model. The intervention is characterized by more intensive service than standard prenatal care, including comprehensive assessments, care coordination, home visiting, and other non-clinical supports. Clinics agreeing to serve as medical homes and participate in the pilot initiative receive additional payments (above the Medicaid payments for prenatal care and delivery) as well as a bonus payment for positive birth outcomes as defined by DHS. Research Goal: To determine if the medical home model is effective in improving birth outcomes among BadgerCare Plus (Medicaid)-enrolled high-risk women in Southeast Wisconsin. Objectives/Specific Aims 1. Measure participating clinics against: a) their individual benchmark measures for the process of prenatal and postpartum care, b) fidelity of implementing the contractual parameters and other attributes of the medical home pilots, and c) how the clinic intervention differs from pre-program standard care. 2. Conduct -

Kurt Hummel's Language Features in Glee Television

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI KURT HUMMEL’S LANGUAGE FEATURES IN GLEE TELEVISION SERIES SEASON 1: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC ANALYSIS A SARJANA PENDIDIKAN THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By Yustina Rostyaningtyas Student Number: 131214113 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2017 i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI “There is no substitute for hard work.” Thomas A. Edison This thesis is dedicated to: Antonius Wiryono, Yuliana Saryati, and myself iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ABSTRACT Rostyaningtyas, Yustina. 2017. Kurt Hummel’s Language Features in Glee Television Series Season 1: A Sociolinguistic Analysis. Yogyakarta: English Language Education Study Program, Sanata Dharma University. The use of language by individuals is influenced by many factors. Gender is one factor that influences the use of language. In this research, gender is seen to be different from sex. It is seen as a social construction rather than as a fixed category. As a result, women and men do not stick to one language style but change it based on their social context. Therefore, the researcher was interested in analyzing the women’s language used by a feminine man named Kurt Hummel in Glee Television Series Season 1. In conducting the research, a research question was formulated: What women’s language features does Kurt Hummel use in his speech in Glee Television Series Season 1? The research was qualitative research in which discourse analysis was employed to analyze the data. -

Brittany Rhoades Cooper, Ph.D

Brittany Rhoades Cooper, Ph.D. WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY 510 JOHNSON TOWERS BUILDING · PULLMAN, WA 99164 PHONE: 509-335-2896 · EMAIL: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. Pennsylvania State University 2005-2009 Human Development and Family Studies Advisor: Mark T. Greenberg, Ph.D. M.S. Pennsylvania State University 2003-2005 Human Development and Family Studies Advisor: Mark T. Greenberg, Ph.D. B.A. University of Arizona 1998-2002 Psychology, Summa Cum Laude with Honors Advisor: Jennifer L. Maggs, Ph.D. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Washington State University Assistant Professor, Human Development 2012-present Graduate Faculty, Prevention Science Youth and Family Extension Specialist Pennsylvania State University Evaluation Research Specialist, EPISCenter 2009-2012 Research Associate, Prevention Research Center 2009-2012 Research Scientist, Methodology Center 2009-2012 NIDA Prevention and Methodology Pre-doctoral Fellow 2005-2007 Research Assistant, Human Development & Family Studies 2003-2009 RESEARCH INTERESTS Grounded in a contextual view of human development, my program of research focuses on both the generation of basic prevention research knowledge and the translation of this knowledge for effective prevention practice and policy aimed at improving the mental, emotional and behavioral health of children, families, and communities. Specifically, my research examines how risk and protective factors at multiple ecological levels, including family, peer, school, and community, interact to predict children’s developmental outcomes. This basic research forms the basis for the development of effective family and school-based prevention programs aimed at promoting healthy development. Once a prevention program has been proven effective, the ultimate goal is widespread dissemination and scale-up, and therefore my research also focuses on the identification and examination of the program, organizational, and community barriers which hinder the successful delivery of preventive interventions under natural conditions. -

Glee 101: Pilot 2009

SHOOTJNG u'Vl1'T 1..UE REVIS ONS 10121/0i; WRITTEN BY: RYAN MURPH • AND BRAD FALCHU...-..--. ~ AND (AN RENNAN Al BLACKNESS. In the void, a sound ... CLAPPING. In SYNCOPATIONAl wit h FOOT STOMPI NG... a crazed crowd demanding a show. Sudden l y , a slit APPEARS in the b:ackness ... which we now realize is a black velvet cur-~ . AS-~ ~ !2:RVOOSTEENAGE BOY peers out . His POV: i.: ' s .:e=:..=:,·::..::g... a :!UGE SOLD OUT AUDITORIUM,everyone vibra-::i..~g wi=~ =~=:..pa1:0=y frenzy . TITLES OP: EPCOT CE!i'l'ER, GLll C:.C'S llA~~ OXU..S, 1993 . 1 INT. BACKSTAGEEPCO~ :-F.2,;.'i'?-E -- -:;;.x - :.:--=:::-.,ccrs 1 The NERVOUS7EN, :u:. a -:t:X, ,c=s ~;:;= ::--=:.a=or so TEENS as they stre-::ch, practice sca:es, e-::c. 0-..e-~:?.:. :..s e~en looking in a .=ti.rro~r p=a~icing a ~:;GE~~ s=:-- F~.::Z.. SuCdenly, their ~eac!'!e.r :.n,r ~ nD:.E?, 5Js t a_;:;p,ea:s. ==::.::.~e tii.~ings, claps her h=ds ::or tilei.::- atten-::-=.o::. MRS. ADLER Show circle, everybody . The teens grasp hands in a circle =o=a J!:"s. ~~-er, .h-=.ch is difficult to do because she's obese . MRS. ADLER ( CO~~ :: ) Welcome to nat i onals. The ki ds whoop and scream with de:ig~-::. - MRS . AD:.E:l CC!-_ :l Fantastic . Use "'Cha~e.x=~~e...,;~~ ~ the stage today. 3c-::: ~a~-:: guys to remember sc~~ - ~'cg. PUSH IN ON THE YOONGNERVOGS -•-S,":...GZ 3~Y as she continues . ~ . ;o- -=?~ c::-!:-:,:: Glee c l ub isn • t abc::= c=eti-::ior:. -

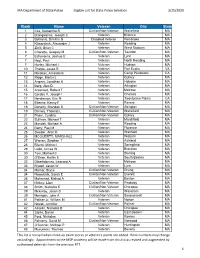

Eligible List for State Police Selection 3/25/2020

MA Department of State Police Eligible List for State Police Selection 3/25/2020 Rank Name Veteran City State 1 Cila, Samantha R Civilian/Non-Veteran Wakefield MA 2 Brangwynne, Joseph C Veteran Billerica MA 3 Bethanis, Dimitris G Disabled Veteran Pembroke MA 4 Klimarchuk, Alexander J Veteran Reading MA 5 Ziniti, Brian C Veteran West Roxbury MA 6 Charette, Gregory M Civilian/Non-Veteran Taunton MA 7 Echevarria, Joshua E Veteran Lynn MA 7 Hoyt, Paul Veteran North Reading MA 7 Hurley, Michael J Veteran Hudson MA 10 Tharpe, Jesse R Veteran Fort Eustis VA 11 Harakas, Amanda K Veteran Camp Pendleton CA 12 Ridge, Martin L Veteran Quincy MA 13 Angers, Jonathan A Veteran Holyoke MA 14 Berg, Alex D Veteran Arlington MA 15 Arsenault, Robert T Veteran Melrose MA 16 Cordes V, Joseph I Veteran Chelsea MA 17 Henderson, Eric N Veteran Twentynine Palms CA 18 Etienne, Kenny F Veteran Revere MA 19 Doherty, Brandon S Civilian/Non-Veteran Abington MA 19 Dorney, Thomas L Civilian/Non-Veteran Wakefield MA 21 Pham, Cynthia Civilian/Non-Veteran Quincy MA 22 Sullivan, Michael T Veteran Marshfield MA 23 Mandell, Michael A Veteran Reading MA 24 Barry, Paul M Veteran Florence MA 25 Sweder, Aron D Veteran Waltham MA 25 MCGUERTY, MARSHALL Veteran Woburn MA 27 Warren, Stephen T Veteran Ashland MA 28 Rivest, Michael Veteran Springfield MA 29 Ladd, James W Veteran Brockton MA 30 Tosi, Michael C Veteran Sterling MA 30 O'Brien, Kaitlin E Veteran South Boston MA 32 Dibartolomeo, Leonard A Veteran Melrose MA 33 Blydell, Jason W Veteran Lynn MA 34 Molnar, Bryce Civilian/Non-Veteran -

Glee, Flash Mobs, and the Creation of Heightened Realities

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction University Libraries Publications and Scholarship University Libraries 9-20-2016 Glee, Flash Mobs, and the Creation of Heightened Realities Elizabeth Downey Mississippi State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/ul-publications Recommended Citation Downey, Elizabeth M. "Glee, Flash Mobs, and the Creation of Heightened Realities." Journal of Popular Film & Television, vol. 44, no. 3, Jul-Sep2016, pp. 128-138. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1080/ 01956051.2016.1142419. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Libraries Publications and Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Glee and Flash Mobs 1 Glee, Flash Mobs, and the Creation of Heightened Realities In May of 2009 the television series Glee (Fox, 2009-2015) made its debut on the Fox network, in the coveted post-American Idol (2002-present) timeslot. Glee was already facing an uphill battle due to its musical theatre genre; the few attempts at a musical television series in the medium’s history, Cop Rock (ABC, 1990) and Viva Laughlin (CBS, 2007) among them, had been overall failures. Yet Glee managed to defeat the odds, earning high ratings in its first two seasons and lasting a total of six. Critics early on attributed Glee’s success to the popularity of the Disney Channel’s television movie High School Musical (2006) and its subsequent sequels, concerts and soundtracks. That alone cannot account for the long-term sensation that Glee became, when one acknowledges that High School Musical was a stand-alone movie (sequels notwithstanding). -

Going Against the Grain "This Is Who I Am

Lopez 1 Going Against the Grain "This is who I am. Nobody said you had to like it." Nicole Lopez April 18, 2010 LAE 4360 Shelbie Witte Lopez 2 Table of Contents Rationale……………………………………………………………………3 Goals and Objectives…………………………………………….................7 Sunshine State Standards…………………………………………………...8 Materials……………………………………………………………………10 Unit Outline………………………………………………………………..11 References………………………………………………………………….21 Appendix A………………………………………………………………..22 Appendix B………………………………………………………………..26 Appendix C………………………………………………………………..27 Appendix D………………………………………………………………..29 Appendix E………………………………………………………………..29 Appendix F………………………………………………………………...30 Appendix G………………………………………………………………..42 Appendix H………………………………………………………………..44 Appendix I…………………………………………………………………46 Appendix J…………………………………………………………………50 Appendix K………………………………………………………………..51 Lopez 3 Rationale This is a five-week unit designed for an eighth grade general English class. The class consists of twenty-two students with each class period being fifty minutes long. This unit will revolve around their daily lives but specifically, how they see themselves and those around them. The theme of the unit is “Going Against the Grain” which pertains to not sticking to stereotypes and how others may view them. I would like to introduce this unit during the third nine weeks, after they come from the winter break. Students are about to go into this new place, high school. Students are probably nervous about going there and may go through some difficulties to try and keep their own identity. Students will be able to connect real life situations to these different literatures. The theme of identity and defining the norm is throughout their daily lives and in pop culture. How we define ourselves can also contribute to how others define us. The theme of self-definition is all over, especially in middle and high schools.