The Global and the Local in Max Cavalera's Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Metal Híbrido Desde Brasil

Image not found or type unknown www.juventudrebelde.cu Metal híbrido desde Brasil Publicado: Jueves 11 octubre 2007 | 12:00:08 am. Publicado por: Juventud Rebelde La ciudad de Belo CubiertaImage not found del or CD:type unknown Dante XXI de la agrupación brasileña Sepultura. Horizonte, ubicada en el estado brasileño de Minas Gerais, fue el sitio que vio nacer, a inicios de los 80 del pasado siglo, a la banda de rock de nuestro continente que más impacto ha registrado a escala universal: el grupo Sepultura. Integrada en un primer momento por los hermanos Cavalera, Max (guitarra y voz), e Igor (batería), junto al bajista Paulo Jr., y Jairo Guedez en una segunda guitarra, la agrupación conserva total vigencia a más de 20 años de fundarse. Las principales influencias que el cuarteto reconoce en sus comienzos, provienen de gentes como Slayer, Sadus, Motörhead y Sacred Reich, quienes les ayudan a conformar un típico sonido de thrash metal. En 1985, a través del sello Cogumelo Produçoes, editan en Brasil su primer trabajo fonográfico, Bestial devastation, un disco publicado en forma de split (como se conoce a un álbum compartido con otra banda), en compañía de los también brasileños de Overdose. El éxito del material sorprende a muchos y así, Cogumelo Produçoes se asocia a Road Runner Records, para sacar al mercado, en 1986, el primer LP íntegro con música de Sepultura, Morbid visions, valorado al paso del tiempo como un clásico del universo metalero, gracias a cortes como War, Crucifixion y, en especial, Troops of doom, tema que pasó a ser una suerte de himno para la banda. -

Metal Extremo: Estética “Pesada” No Black Metal

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE JUIZ DE FORA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS – ICH PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS LUANA CRISTINA SEIXAS METAL EXTREMO: ESTÉTICA “PESADA” NO BLACK METAL Juiz de Fora 2018 LUANA CRISTINA SEIXAS METAL EXTREMO: ESTÉTICA “PESADA” NO BLACK METAL ORIENTADORA: Elizabeth de Paula Pissolato Juiz de Fora 2018 LUANA CRISTINA SEIXAS METAL EXTREMO: ESTÉTICA “PESADA” NO BLACK METAL Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Ciências Sociais do Instituto de Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, como parte dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciências Sociais. Orientadora: Prof.ª Drª. Elizabeth de Paula Pissolato Juiz de Fora 2018 Fiiha iatalográfia elaboraaa através ao "rograma ae geração automátia aa Biblioteia Universitária aa UFJF, iom os aaaos forneiiaos "elo(a) autor(a) SEIXAS, Luana Cristnaa Metal extremo: : estétia "esaaa no Blaik Metal / Luana Cristna SEIXASa -- 2018a 75 "a : ila Orientaaora: Elizabeth ae Paula Pissolato Dissertação (mestraao aiaaêmiio) - Universiaaae Feaeral ae Juiz ae Fora, Insttuto ae Ciêniias Humanasa Programa ae Pós Graauação em Ciêniias Soiiais, 2018a 1a Est1a Estétiaa 2a Blaik Metala 3a Juiz ae Foraa Ia Pissolato, Elizabeth ae Paula, orienta IIa Títuloa AGRADECIMENTOS Este trabalho apenas se tornou possível devido à contribuição e compreensão de várias pessoas. Agradeço aos meus pais, que no início da faculdade, quando nem compreendiam a minha área de atuação e me deram todo o apoio e que hoje explicam com orgulho o que sua filha estuda, até mesmo para os desconhecidos. Por me apresentar ao Rock quando ainda criança, e quando a situação se inverteu e eu apresentei o Metal, eles estavam abertos a conhecer. -

Heavy Metal and Classical Literature

Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 ROCKING THE CANON: HEAVY METAL AND CLASSICAL LITERATURE By Heather L. Lusty University of Nevada, Las Vegas While metalheads around the world embrace the engaging storylines of their favorite songs, the influence of canonical literature on heavy metal musicians does not appear to have garnered much interest from the academic world. This essay considers a wide swath of canonical literature from the Bible through the Science Fiction/Fantasy trend of the 1960s and 70s and presents examples of ways in which musicians adapt historical events, myths, religious themes, and epics into their own contemporary art. I have constructed artificial categories under which to place various songs and albums, but many fit into (and may appear in) multiple categories. A few bands who heavily indulge in literary sources, like Rush and Styx, don’t quite make my own “heavy metal” category. Some bands that sit 101 Lusty, “Rocking the Canon” LATCH, Vol. 6, 2013, pp. 101-138 on the edge of rock/metal, like Scorpions and Buckcherry, do. Other examples, like Megadeth’s “Of Mice and Men,” Metallica’s “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” and Cradle of Filth’s “Nymphetamine” won’t feature at all, as the thematic inspiration is clear, but the textual connections tenuous.1 The categories constructed here are necessarily wide, but they allow for flexibility with the variety of approaches to literature and form. A segment devoted to the Bible as a source text has many pockets of variation not considered here (country music, Christian rock, Christian metal). -

Harmonic Resources in 1980S Hard Rock and Heavy Metal Music

HARMONIC RESOURCES IN 1980S HARD ROCK AND HEAVY METAL MUSIC A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Theory by Erin M. Vaughn December, 2015 Thesis written by Erin M. Vaughn B.M., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ____________________________________________ Richard O. Devore, Thesis Advisor ____________________________________________ Ralph Lorenz, Director, School of Music _____________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER I........................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................................ 3 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE............................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................... 36 ANALYSIS OF “MASTER OF PUPPETS” ...................................................................................... -

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal *

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal * Stephen S. Hudson NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hudson.php KEYWORDS: Heavy Metal, Formenlehre, Form Perception, Embodied Cognition, Corpus Study, Musical Meaning, Genre ABSTRACT: This article presents a new framework for analyzing compound AABA form in heavy metal music, inspired by normative theories of form in the Formenlehre tradition. A corpus study shows that a particular riff-based version of compound AABA, with a specific style of buildup intro (Aas 2015) and other characteristic features, is normative in mainstream styles of the metal genre. Within this norm, individual artists have their own strategies (Meyer 1989) for manifesting compound AABA form. These strategies afford stylistic distinctions between bands, so that differences in form can be said to signify aesthetic posing or social positioning—a different kind of signification than the programmatic or semantic communication that has been the focus of most existing music theory research in areas like topic theory or musical semiotics. This article concludes with an exploration of how these different formal strategies embody different qualities of physical movement or feelings of motion, arguing that in making stylistic distinctions and identifying with a particular subgenre or style, we imagine that these distinct ways of moving correlate with (sub)genre rhetoric and the physical stances of imagined communities of fans (Anderson 1983, Hill 2016). Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory “Your favorite songs all sound the same — and that’s okay . -

Helloween Destruction Morbid Angel Audrey Horne

CD-BACKCOVER ZUMSELBERBASTELN!EINFACHANDENMARKIERUNGENAUSSCHNEIDENUNDINEINECD-BLANKO-HÜLLELEGEN.FERTIG! GEMA 1. HELLOWEEN - Pumpkins United 6:21 12.2017 (Kai Hansen, Andi Deris, Michael Weikath) BMG Rights Management* Nuclear Blast/Warner 2. DESTRUCTION - United By Hatred 4:36 (Michael Sifringer, Marcel Schirmer) Wintrup Musikverlage* Nuclear Blast/Warner LAUSCHANGRIFF 3. MORBID ANGEL - Piles Of Little Arms 3:44 (Azagthoth/Tucker) Azagthoth and Tucker* Silver Lining/Warner VOL.059 4. AUDREY HORNE - This Is War 6:17 (Torkjell Rød, Arve Isdal, Thomas Tofthagen, Espen Lien, Kjetil Greve) Iron Avantgarde Publishing* Napalm/Universal 5. HARD ACTION - Nothing Ever Changed 3:15 (Ville Valavuo, Gunther Kivioja) Copyright Control* Svart/Cargo 6. CAVALERA CONSPIRACY - Insane 3:50 (Max Cavalera, Iggor Cavalera, Marc Rizzo/Max Cavalera) Kobalt Music Publishing Ltd.* Napalm/Universal 7. STÄLKER - Shadow Of The Sword 3:28 (David John Rynhart King, Christopher Calavrias, Nicholas George Oakes/David John Rynhart King, Christopher Calavrias) Iron Avantgarde Publishing* Napalm/Universal 8. JESS AND THE ANCIENT ONES - Return To Hallucinate 2:28 VOL.059 (Thomas Corpse) Copyright Control* Svart/Cargo LAUSCHANGRIFF 9. DEGIAL - Annihilation Banner 4:17 (Degial) Sepulchral Voice/Soulfood 10. HAMFERD - Hon Syndrast 6:06 (Theodor Kapnas, Jón Aldará, Remi Kofoed Johannesen, John Egholm, Esmar Joensen, Ísak Petersen) Metal Blade/Sony 12.2017 11. ALMANAC - Hail To The King (Edit) 4:58 (Victor Smolski/Andy Franck) Copyright Control* Nuclear Blast/Warner 12. THE WEIGHT - Hard Way 2:47 (Tobias Jussel, Patrick Moosbrugger, Michael Boebel, Andreas Vetter) Copyright Control* Heavy Rhythm & Roll/Rough Trade. -

Metaldata: Heavy Metal Scholarship in the Music Department and The

Dr. Sonia Archer-Capuzzo Dr. Guy Capuzzo . Growing respect in scholarly and music communities . Interdisciplinary . Music theory . Sociology . Music History . Ethnomusicology . Cultural studies . Religious studies . Psychology . “A term used since the early 1970s to designate a subgenre of hard rock music…. During the 1960s, British hard rock bands and the American guitarist Jimi Hendrix developed a more distorted guitar sound and heavier drums and bass that led to a separation of heavy metal from other blues-based rock. Albums by Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple in 1970 codified the new genre, which was marked by distorted guitar ‘power chords’, heavy riffs, wailing vocals and virtuosic solos by guitarists and drummers. During the 1970s performers such as AC/DC, Judas Priest, Kiss and Alice Cooper toured incessantly with elaborate stage shows, building a fan base for an internationally-successful style.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . “Heavy metal fans became known as ‘headbangers’ on account of the vigorous nodding motions that sometimes mark their appreciation of the music.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . Multiple sub-genres . What’s the difference between speed metal and death metal, and does anyone really care? (The answer is YES!) . Collection development . Are there standard things every library should have?? . Cataloging . The standard difficulties with cataloging popular music . Reference . Do people even know you have this stuff? . And what did this person just ask me? . Library of Congress added first heavy metal recording for preservation March 2016: Master of Puppets . Library of Congress: search for “heavy metal music” April 2017 . 176 print resources - 25 published 1980s, 25 published 1990s, 125+ published 2000s . -

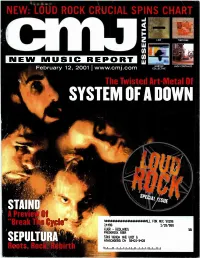

System of a Down Molds Metal Like Silly Putty, Bending and Shaping Its Parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment Ters to Fit the Band's Twisted Vision

NEW: LOUD ROCK CRUCIAL SPINS CHART LOW TORTOISE 1111 NEW MUSIC REPORT Uà NORTEC JACK COSTANZO February 12, 20011 www.cmj.com COLLECTIVE The Twisted Art-Metal Of SYSTEM OF ADOWN 444****************444WALL FOR ADC 90138 24438 2/28/388 KUOR - REDLAHDS FREDERICK SUER S2V3HOD AUE unr G ATASCADER0 CA 88422-3428 IIii II i ti iii it iii titi, III IlitlIlli lilt ti It III ti ER THEIR SELF TITLED DEBUT AT RADIO NOW • FOR COLLEGE CONTACT PHIL KASO: [email protected] 212-274-7544 FOR METAL CONTACT JEN MEULA: [email protected] 212-274-7545 Management: Bryan Coleman for Union Entertainment Produced & Mixed by Bob Marlette Production & Engineering of bass and drum tracks by Bill Kennedy a OADRUNNEll ACME MCCOWN« ROADRUNNER www.downermusic.com www.roadrunnerrecords.com 0 2001 Roadrunner Records. Inc. " " " • Issue 701 • Vol 66 • No 7 FEATURES 8 Bucking The System member, the band is out to prove it still has Citing Jane's Addiction as a primary influ- the juice with its new release, Nation. ence, System Of A Down molds metal like Silly Putty, bending and shaping its parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment ters to fit the band's twisted vision. Loud Follies Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto taps SOAD for Free speech is fodder for the courts once the scoop on its upcoming summer release. again. This time the principals involved are a headbanger institution and the parents of 10 It Takes A Nation daughter who was brutally murdered by three Some question whether Sepultura will ever of its supposed fans. be same without larger-than-life frontman 15 CM/A: Staincl Max Cavalera. -

Exploring the Chinese Metal Scene in Contemporary Chinese Society (1996-2015)

"THE SCREAMING SUCCESSOR": EXPLORING THE CHINESE METAL SCENE IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE SOCIETY (1996-2015) Yu Zheng A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2016 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton Kristen Rudisill © 2016 Yu Zheng All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This research project explores the characteristics and the trajectory of metal development in China and examines how various factors have influenced the localization of this music scene. I examine three significant roles – musicians, audiences, and mediators, and focus on the interaction between the localized Chinese metal scene and metal globalization. This thesis project uses multiple methods, including textual analysis, observation, surveys, and in-depth interviews. In this thesis, I illustrate an image of the Chinese metal scene, present the characteristics and the development of metal musicians, fans, and mediators in China, discuss their contributions to scene’s construction, and analyze various internal and external factors that influence the localization of metal in China. After that, I argue that the development and the localization of the metal scene in China goes through three stages, the emerging stage (1988-1996), the underground stage (1997-2005), the indie stage (2006-present), with Chinese characteristics. And, this localized trajectory is influenced by the accessibility of metal resources, the rapid economic growth, urbanization, and the progress of modernization in China, and the overall development of cultural industry and international cultural communication. iv For Yisheng and our unborn baby! v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to show my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Dr. -

Extreme Metal: Subculture, Genre, and Structure

Université de Montréal Extreme metal: Subculture, Genre, and Structure par Samaël Pelletier Université de Montréal Faculté de Musique Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de Maîtrise en musique option musicologie avril 2018 © Samaël Pelletier. 2018 Abstract Extreme metal is a conglomeration of numerous subgenres with shared musical and discursive tendencies. For the sake of concision, the focus throughout this thesis will mainly be on death metal and black metal – two of the most popular subgenres categorized under the umbrella of extreme metal. Each chapter is a comparative analysis of death metal and black metal from different perspectives. Thus, Chapter One is historical account of extreme metal but also includes discussions pertaining to iconography and pitch syntax. Subsequently, Chapter Two concerns itself with the conception of timbre in death metal and black metal. More specifically, timbre will be discussed in the context of sound production as well as timbre derived from performance, in particular, vocal distortion. The conception of rhythm/meter will be discussed in Chapter Three which will simultaneously allow for a discussion of the fluidity of genre boundaries between death metal and progressive metal – largely because of the importance placed on rhythm by the latter subgenre. Instead of a focus on musical practices, Chapter Four will instead take a sociological approach with the aim of answering certain issues raised in the first three chapters. Ultimately, this thesis aims to elucidate two questions: What are the different aesthetic intentions between practitioners of death metal and black metal? And, how do fans conceptualize these aesthetic differences? Sarah Thornton’s notion of subcultural capital – which is derived from Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of cultural capital – will help to answer such questions. -

ATTIKA 7 -- New Metal Band Featuring Biohazard's Evan

For Immediate Release September 26th, 2011 ATTIKA 7 -- New Metal Band Featuring Biohazard's Evan Seinfeld, Soulfly's Tony Campos, Walls of Jericho's Dustin Schoenhofer, and Master Bike Builder, Lead Guitarist and Songwriter Rusty Coones – Recording New Album Now ATTIKA 7 is a brand new force in the ever-evolving heavy metal world, featuring Evan Seinfeld, formerly of Biohazard, lead guitarist, songwriter and famed motorcycle builder Rusty Coones, bassist Tony Campos, founding member of Static X, who also currently performs in Soulfly, Prong, Possessed, Asesino and Ministry, and drummer Dustin Schoenhofer from Walls of Jericho and Bury Your Dead fame. ATTIKA 7 will be releasing their debut album later this year and are currently working on their first video for the single ‘Serial Killer’. The band describes their lyrics and ideology as genuine and conveys a true American outlaw lifestyle. The ATTIKA 7 sound boasts very heavy, down-tuned and melodic harmonies, all the while boasting brutal hooks and grooves. The band draws from several musical influences, including their own additional projects, and has been compared to the likes of Black Sabbath, Metallica, Godsmack, Pantera, and White Zombie. The timeless no-frills songwriting of ATTIKA 7 is set apart from today’s homogenized, derivative copycat bands by so many things, but above all: authenticity. The majority of the album was written by lifetime biker and ATTIKA 7 lead guitarist Rusty Coones while serving a seven-year federal prison sentence for a false conviction. Rather than rat on his friends, Rusty used the tension to teach himself how to play guitar in solitary confinement.