Angkor Children's Hospital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Members Members

PENNSYLVANIA DENTAL JOURNAL Members DiffeMraekinng Ace VOLUNTEERIING IIN SIIEM REAP,, CAMBODIIA 1 n , 1 8 v / 4 1 0 2 B E F / N A J Officers 6th | Dr. John P. Grove | 2014 G PDA Central Office Dr. R. Donald Hoffman (President ) +L3 PO Box 508, Jersey Shore, 17740-0508 3501 North Front Street 105 Penhurst Drive, Pittsburgh, 15235 (570) 398-2270 • [email protected] P.O. Box 3341, Harrisburg, 17105 (412) 648-1915 • [email protected] 7th | Dr. Wade I. Newman | 2014 G (800) 223-0016 • (717) 234-5941 Dr. Stephen T. Radack III (President-Elect ) +3L Bellefonte Family Dentistry FAX (717) 232-7169 413 East 38th Street, Erie, 16504 115 S. School St., Bellefonte, 16823-2322 Camille Kostelac-Cherry, Esq. (814) 825-6221 • [email protected] (814) 355-1587 • [email protected] Chief Executive Officer Dr. Bernard P. Dishler (Imm. Past President ) LL 8th | Dr. Thomas C. Petraitis | 2015 + [email protected] Yorktowne Dental Group Ltd. 101 Hospital Ave., DuBois, 15801-1439 Mary Donlin 8118 Old York Road Ste A • Elkins Park, 19027-1499 (814) 375-1023 • [email protected] Director of Membership (215) 635-6900 • [email protected] 9th | Dr. Joseph E. Ross | 2016 G [email protected] Dr. James A.H. Tauberg (Vice President) Olde Libray Office Complex Marisa Swarney 224 Penn Ave., Pittsburgh, 15221 106 E. North St., New Castle, 16101 Director of Government Relations (412) 244-9044 • [email protected] (724) 654-2511 • [email protected] [email protected] Dr. Peter P. Korch III (Speaker) GG 10th | Dr. Herbert L. Ray Jr. | 2015 + Rob Pugliese 4200 Crawford Ave., NorCam Bldg. -

Implementation of Single-Use Anesthesia Circuit Disinfection Guidelines in a Resource-Scarce Setting

Implementation of Single-use Anesthesia Circuit Disinfection Guidelines in a Resource-scarce Setting Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Johnston, Rachel Citation Johnston, Rachel. (2021). Implementation of Single-use Anesthesia Circuit Disinfection Guidelines in a Resource-scarce Setting (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 06:12:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/658601 IMPLEMENTATION OF SINGLE-USE ANESTHESIA CIRCUIT DISINFECTION GUIDELINES IN A RESOURCE-SCARCE SETTING by Rachel M. Johnston ________________________ Copyright © Rachel M. Johnston 2021 A DNP Project Submitted to the Faculty of the COLLEGE OF NURSING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF NURSING PRACTICE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 2 1 2 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To my fiancé Andy, thank you. I wonder every day how I got so lucky to cross your path in a tiny town in Guatemala. I wonder how it is that you have so tirelessly supported me through every crazy idea and seemingly unobtainable goal I have put in front of us. I wonder what I would have done without you through these last three years that have felt like they would never end. Thank you for always making me laugh, for being a temporary single parent to our two fat cats, and to holding it together when all I wanted to do was fall apart. -

For More Information About the New Jersey Employees Charitable Campaign

1 2 Table of Contents Letter from Governor Murphy ………………………………….…..………..2 General Information About the NJECC …………………………….………4 What Will My Gift Provide …………………………………………………..…..6 How to Fill Out a Pledge Form …………………………………………….……7 2017 NJECC Award Winners ……………………………….…………………..8 Federations: Community Health Charities ………………………….……………..………..9 America’s Charities ………………………………………………………….……11 Global Impact ……………………………………………………………..…………13 EarthShare New Jersey …………………………………………….………….…14 Neighbor to Nation …………………………………………………..……………16 America’s Best Charities …………………………………………..……………17 United Way of Greater Mercer County ……………………..…………..26 United Way of Gloucester County ……………………………..………….27 United Way of Monmouth & Ocean Counties …………………..…..27 United Way of Greater Union County ……………………………..…….29 Jewish Federation of Greater MetroWest NJ …………………..…….30 United Way of Essex & West Hudson County ……………………..…30 Jewish Federation of Middlesex & Monmouth County ………….31 Unaffiliated Agencies …………………………………………………………….31 Alphabetical Agency Index ………………………………………………..37 PLEASE NOTE: All information contained in this codebook was supplied by the various federations and agencies as of June 2018. Errors, omissions, and other problems are the responsibility of the organization submitting the information to this campaign. 3 What is the NJECC? Thanks to legislation that created the New Jersey Employees Charitable Campaign in 1985, employees of state agencies, universities, county government, municipalities and school districts throughout New Jersey enjoy the benefit of giving to many of their favorite charities through an annual workplace giving campaign which features the convenience of payroll deduction. Donations exceeded $815,000 for charitable organizations in 2017. How does it work? Each fall, we get the opportunity to learn about the charities in the NJECC and choose which ones we want to help, and then go online or fill out a paper pledge form to indicate how much we wish to donate to which groups. -

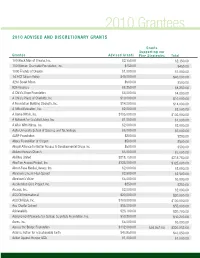

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised and Discretionary Grants

2010 Grantees 2010 Advised And discretionAry GrAnts Grants supporting our Grantee Advised Grants Five strategies total 100 Black Men of Omaha, Inc. $2,350.00 $2,350.00 100 Women Charitable Foundation, Inc. $450.00 $450.00 1000 Friends of Oregon $1,000.00 $1,000.00 1st ACT Silicon Valley $40,000.00 $40,000.00 42nd Street Moon $500.00 $500.00 826 Valencia $8,250.00 $8,250.00 A Child’s Hope Foundation $4,000.00 $4,000.00 A Child’s Place of Charlotte, Inc. $10,000.00 $10,000.00 A Foundation Building Strength, Inc. $14,000.00 $14,000.00 A Gifted Education, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 A Home Within, Inc. $105,000.00 $105,000.00 A Network for Grateful Living, Inc. $1,000.00 $1,000.00 A Wish With Wings, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Aalto University School of Science and Technology $6,000.00 $6,000.00 AARP Foundation $200.00 $200.00 Abbey Foundation of Oregon $500.00 $500.00 Abigail Alliance for Better Access to Developmental Drugs Inc $500.00 $500.00 Abilene Korean Church $3,000.00 $3,000.00 Abilities United $218,750.00 $218,750.00 Abortion Access Project, Inc. $325,000.00 $325,000.00 About-Face Media Literacy, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 Abraham Lincoln High School $2,500.00 $2,500.00 Abraham’s Vision $5,000.00 $5,000.00 Accelerated Cure Project, Inc. $250.00 $250.00 Access, Inc. $2,000.00 $2,000.00 ACCION International $20,000.00 $20,000.00 ACCION USA, Inc. -

Annual Report 2013 Medical Was a Very 2013 Special Leadership Year for Angkor Hospital for Children

Angkor Hospital for Children ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Medical was a very 2013 special Leadership year for Angkor Hospital for Children. Message Since first opening its gates in 1999, the goal Dear friends, of founder Kenro Izu It is exciting to think of the many accomplishments of Angkor was to make AHC “a Hospital for Children (AHC) in 2013. These were not imaginable world class hospital when the hospital opened 14 years ago. This year’s annual report, the first ever produced by AHC, highlights the following major for Cambodians run by accomplishments: the beginning of cancer treatment at AHC for Cambodians.” With the eye cancer patients, the growing independence of AHC’s cardiac end of a one-year long surgery team, and the opening of a new neonatal ward made possible by the opening of a new 990 square meter building. An transitional phase that additional success of 2013 was an increased focus on quality and culminated in January transparency in administrative processes. of 2013, Kenro’s original The transition of AHC to a locally run Asian-based organization vision for the hospital with diversified worldwide support and stakeholders has created was realized when AHC new opportunities. Importantly, the essential education that AHC became an independent provides is set to expand. We in the medical leadership team are excited and thankful to have a growing influence on the training organization firmly of medical students and junior doctors in Cambodia. We believe rooted in Siem Reap and that such training will impact children’s healthcare in Cambodia for led by an outstanding years to come. -

2014 Annual Report Will Convey the Significance Presentations and Lectures

Angkor Hospital for Children ANNUAL REPORT 2014 Medical AHC has distinguished Leadership itself as the premier children’s teaching Message hospitals in northern Cambodia. ast year alone, AHC had Dear Friends, more than 168,000 patient 2014 was an extremely exciting year at Angkor Hospital visits and educated more for Children. Our accomplishments this year are the result L of incredibly hard-working and dedicated staff, as well than 10,000 healthcare workers as our wonderful partners, volunteers and donors. AHC underwent many physical changes this year: we were able from AHC and local organizations. to complete the renovation of our Outpatient Department, Throughout the year, there thus decreasing chronic over-crowding and giving patients the privacy they deserve and we began construction on were multiple opportunities for an extension for the Emergency Room and Intensive Care medical and non-medical staff Unit that will allow us to separate emergency and non- emergency patients better than ever before. to improve their knowledge through Continuing Medical I hope you delight in reading about the many achievements of 2014 including the treatment of 14 Education (CME), Continuing patients with eye cancer; AHC’s doctors performed their first unassisted open heart surgery, and the increase in our Nursing Education (CNE), bedside residency program. training and case review; the AHC’s staff remains unwaveringly dedicated to Kenro Izu’s AHC Residency Program; local, founding vision, and work tirelessly to provide quality national and international training, compassionate care to Cambodia’s children. We hope that the 2014 Annual Report will convey the significance presentations and lectures. -

SEFA Catalog 2017-18 (PDF)

127480 SEFA 2017.qxp 9/13/17 9:41 AM Page 1 127480 SEFA 2017.qxp 9/13/17 9:41 AM Page 2 www.sefanys.org/pledge Make your pledge on-line when it’s convenient for you! The campaign website (www.sefanys.org) allows you to search for allowable charities • By Name • By area • By keyword Or you can browse this charity book. Both the website and this charity book lists: • Contact information • Federal ID # • Administrative and fundraising rate Coming Soon…….. Retirees will be able to participate in the SEFA campaign through their retirement checks. Information will be announced on SEFA website and on Facebook. 127480 SEFA 2017.qxp 9/13/17 9:41 AM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS STATE EMPLOYEES FEDERATED APPEAL (SEFA) INTRODUCTION . .2 ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF STATEWIDE & LOCAL CHARITIES . .3 FEDERATIONS INDEX . .97 America’s Best Charities . .97 America’s Best Local Charities . .98 America’s Charities . .98 Animal Charities of America . .98 Children’s Charities of America . .98 Community Health Charities . .98 Community Works of NYS . .99 EarthShare New York . .99 Global Impact . .99 Health and Medical Research Charities of America . .100 Human & Civil Rights Organizations of America . .100 Neighbor To Nation . .100 CAMPAIGN AREA INDEX . .101 Allegany . .101 Broome/Chenango/Tioga . .101 Capital Region . .101 Central New York . .102 Chautauqua . .103 Chemung . .103 Clinton/Essex/Franklin/Hamilton . .103 Cortland . .103 Delaware/Otsego . .104 Dutchess . .104 Greater Rochester . .104 Herkimer/Madison/Oneida . .105 Jefferson/Lewis . .105 Long Island . .106 New York City . .107 Niagara Frontier . .107 Orange . .109 Rockland . .109 St. Lawrence . .109 Statewide . -

Morton * Burleigh Kidder * Stutsman

2015 Southwest North Dakota Combined Federal Campaign The CFC Represents 7 Counties BILLINGS * STARK * MERCER * MORTON BILLINGSBURLEIGH * * STARKKIDDER * *STUTSMAN MERCER MORTON * BURLEIGH KIDDER * STUTSMAN Dear Fellow Federal Employee: It is that time of year again when we are given an opportunity to consider a monetary donation to the Combined Federal Campaign (CFC). Federal employees have the opportunity to donate to those less fortunate through the CFC. There are people all over the country who have lost their jobs or in need of extra help. The CFC is the only authorized solicitation of employees in the federal workplace on behalf of charitable organizations, and you decide where your donation should go. You can make a one-time cash or check donation, or use the payroll deduction method. The payroll deduction is quick, easy, and the sacrifice of giving is spread out over the entire year. Please consider giving even small amounts to a charity of your choice, we only ask once a year. ...THANK YOU... Local Federal Coordinating Committee Southwest North Dakota Combined Federal Campaign 2014 Southwestern North Dakota CFC Hero Club The Southwestern North Dakota Combined Federal Campaign Hero Club recognizes individuals who provide exceptional leadership in charitable giving in CFC. You become a Hero Club member by making a contribution that reaches a designated level. 24 Karat ($5,000 and above) Platinum ($2,500 to $4,999) FAA, Airport District Office Gold ($1,000 to $2,499) USDA Forest Services US District Court Social Security Administration -

Brown in the Lesser Developed World

Volume 90 No. 11 November 2007 Brown In the Lesser Developed World UNDER THE JOINT VOLUME 90 NO. 11 November 2007 EDITORIAL SPONSORSHIP OF: Medicine Health The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University HODE SLAND Eli Y. Adashi, MD, Dean of Medicine R I & Biological Science PUBLICATION OF THE RHODE ISLAND MEDICAL SOCIETY Rhode Island Department of Health David R. Gifford, MD, MPH, Director COMMENTARIES Quality Partners of Rhode Island 338 Personal Reflections On This Issue Richard W. Besdine, MD, Chief Medical Officer Joseph H. Friedman, MD Rhode Island Medical Society 339 The Serendipitous Gift of Epiphany Barry W. Wall, MD, President Stanley M. Aronson, MD EDITORIAL STAFF Joseph H. Friedman, MD CONTRIBUTIONS Editor-in-Chief Joan M. Retsinas, PhD Brown In the Less Developed World Managing Editor Guest Editors: Susan Cu-Uvin, MD, and David Pugatch, MD Stanley M. Aronson, MD, MPH 340 A Message From the Dean Editor Emeritus Eli Y. Adashi, MD EDITORIAL BOARD 340 Brown’s Involvement In the Health of Less Developed Countries Stanley M. Aronson, MD, MPH Susan Cu-Uvin, MD, and David Pugatch, MD Jay S. Buechner, PhD John J. Cronan, MD 342 Brown’’s Fogarty International Center AIDS International Research and James P. Crowley, MD Training Program: Building Capacity and New Collaborations Edward R. Feller, MD John P. Fulton, PhD Kenneth H. Mayer, MD, and Eileen Caffrey Peter A. Hollmann, MD 346 The Dual Burden of Infectious and Non-Communicable Diseases in the Sharon L. Marable, MD, MPH Anthony E. Mega, MD Asia-Pacific Region: Examples from The Philippines and the Samoan Islands Marguerite A. -

The Lake Clinic – Providing Primary Care to Isolated Floating Villages on the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia

PROJECT REPORT The Lake Clinic – providing primary care to isolated floating villages on the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia HS Merali 1, JF Morgan 2, S Uk 2, S Phlan 2, LT Wang 3, S Korng 2 1Division of Paediatric Emergency Medicine, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 2The Lake Clinic - Cambodia, Siem Reap, Cambodia 3Pediatric Emergency Medicine Services, Division of Global Health, MassGeneral Hospital for Children, Boston, MA, USA Submitted: 3 April 2013; Revised: 17 September 2013; Accepted: 20 September 2013; Published: 8 May 2014 Merali HS, Morgan JF, Uk S, Phlan S, Wang LT, Korng S The Lake Clinic – providing primary care to isolated floating villages on the Tonle Sap Lake, Cambodia Rural and Remote Health 14: 2612. (Online) 2014 Available: http://www.rrh.org.au A B S T R A C T Context: One of the most isolated areas in South-East Asia is the Tonle Sap Lake region in Cambodia. Scattered throughout the lake are remote fishing villages that are geographically isolated from the rest of the country. Issue: Receiving health care at a clinic or hospital often involves a full day of travel from the Tonle Sap Lake region, which is unaffordable for the vast majority of residents. Intervention: The Lake Clinic (TLC) is a non-government organization established in 2007. In 2008, a ship was built that was designed for transport of a medical team and supplies to provide primary care to the fishing villages. Initially the project started with one team serving seven villages. TLC has since expanded to two full teams serving 19 villages. -

Campaign Charity Listing

TOGETHER WE CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE! CAMPAIGN CHARITY LISTING (DCAS Rev. 05.28.19) participating in NYC Gives. EarthShare then distributes these funds equally to all actively participating NYC Gives charities. If you would like to change or cancel your contribution to the NYC Gives General Fund, please contact your NYC Gives liaison. NYC Gives General Fund ........................................... 3 What is the Impact of Your Contribution? America’s Charities Federation ................................... 3 Your contribution will help organizations invest in youth and character Asian American Federation ......................................... 4 development, education/job training, healthy families, health related Children’s Charities of America Federation ................. 5 services, emergency support, and community investment. Community Health Charities Federation...................... 6 Charitable Giving Notice EarthShare New York Federation ................................ 7 All deductions through NYC Gives are tax-deductible. A record of Global Impact Federation............................................ 9 your NYC Gives deductions can be viewed and printed via the ‘Deduction Inquiry’ page in Employee Self-Service (ESS) at Health & Medical Research Charities of America www.nyc.gov/ess Federation ......................................................... 11 EarthShare (EIN 52-1601960) has been selected as the fiscal agent for Human and Civil Rights Organizations of America NYC Gives. A copy of the most recent EarthShare financial -

Here’S Something for Everyone

1 2 Table of Contents Letter from Governor Murphy ………………………………….…..………..2 General Information About the NJECC …………………………….………4 What Will My Gift Provide …………………………………………………..…..6 How to Fill Out a Pledge Form …………………………………………….……7 2018 NJECC Award Winners ……………………………….…………………..8 Federations: America’s Charities ………………………………………………………….…..…9 Global Impact ……………………………………………………………..…………10 EarthShare New Jersey …………………………………………….………….…13 Neighbor to Nation …………………………………………………..……………14 America’s Best Charities …………………………………………..……………16 United Way of Greater Mercer County ……………………..…………..26 United Way of Gloucester County ……………………………..………….27 United Way of Monmouth & Ocean Counties …………………..…..27 United Way of Greater Union County ……………………………..…….29 Jewish Federation of Greater MetroWest NJ (UJA) .………..…….30 Jewish Federation of Middlesex & Monmouth Counties ……….31 Community Health Charities…..……………………….……………..…..….31 Unaffiliated Agencies …………………………………………………………….33 Alphabetical Agency Index…..……………………………………………..41 PLEASE NOTE: All information contained in this codebook was supplied by the various federations and agencies as of May 2019. Errors, omissions, and other problems are the responsibility of the organization submitting the information to this campaign. 3 What is the NJECC? Thanks to legislation that created the New Jersey Employees Charitable Campaign in 1985, employees of state agencies, universities, county government, municipalities and school districts throughout New Jersey enjoy the benefit of giving to many of their favorite charities through an annual workplace giving campaign that features the convenience of payroll deduction. Donations exceeded $878,000 for charitable organizations in 2018. How does it work? Each fall, we get the opportunity to learn about the charities in the NJECC and choose which ones we want to help, and then go online or fill out a paper pledge form to indicate how much we wish to donate to which groups. You can make a one-time gift by check.