Hungary Diary.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gerrit Swanepoel DUBBING MIXER

Gerrit Swanepoel DUBBING MIXER C R E D I T L I S T Horizon – Trail – The Lost Tribes Of Humanity Factual - 1x60’ - BBC2 - BBC Factual All Together Now: The Great Orchestra Challenge Factual - 4x60’ - BBC2 & 4 - BBC Music Coach Trip - Road To Ibiza Light Entertainment - 30x30’- E4 - 12 Yard Separated at Birth Factual - 7x60’ - TLC – CTVC British Army Girls Factual - 1x60’ - Lion TV – Channel 4 The Real Story Of…. Factual–10 x 60' - Discovery - World Media Rights Great British Benefits Handout Factual - 4x60’ - Channel 5 - Dragonfly TV PQ 17: An Arctic Convoy Disaster Factual - 1 x 60’ - BBC2 - BBC Factual Steve Backshall's Extreme Mountain Challenge Factual - 2 x 60’ - BBC2 - BBC Factual Psychedelic Britannia Factual - 1x60' - BBC4 - BBC Factual Music Moguls: Mythmakers Factual - 1x60' - BBC4 - BBC Music Britain's Bomb Factual - 1x60' - BBC – BBC 4 Wonders Of Nature Factual - 6x30' - BBC – BBC Science George Clarke's Amazing Spaces Series 1-4 Factual - 26 x 60’ - Channel 4 - Plum Pictures Sex And The West Factual 3 x 60’ - BBC2 - BBC Factual My Life: Mr Alzheimers and Me Factual - 1 x 30' - CBBC - Tigerlily Films World’s Most Extreme: Airports Factual Entertainment - 1 x 60’ - More4 - Arrow Media Border Country: The Story Of Britain's Lost Middleland Factual - 2 x 60’ - BBC2 - BBC Factual Come Dine Champion Of Champions Factual - 20 x 60’– Channel 4 - Shiver Hair Factual - 1 x 30' - BBC Series Horizon - First Britons Factual - 1 x 60' – BBC2 – BBC Factual Jodie Marsh: Women Who Pay For Sex Factual - 1 x 60’ - Discovery TLC - Thumbs Up -

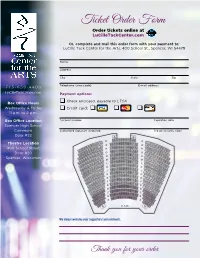

Ticket Order Form Order Tickets Online at Lucilletackcenter.Com

Ticket Order Form Order tickets online at LuCilleTackCenter.com Or, complete and mail this order form with your payment to: LuCille Tack Center for the Arts, 400 School St., Spencer, WI 54479 Name Address City State Zip 715-659-4499 Telephone (area code) E-mail address LuCilleTackCenter.com Payment options: Check enclosed, payable to LTCA Box Office Hours Wednesday & Friday Credit card: 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. Box Office Location Account number Expiration date Spencer High School Commons Authorized signature (required) 3-digit Security Code Door #22 Theatre Location 400 School Street Door #20 Spencer, Wisconsin STAGE We always welcome your suggestions and comments. Thank you for your order Ticket Order Form Step 1 LuCille’s Vision Series (Reserved Seating) Total # Total $ Seating Preference Backtrack Vocals $20 Sunday, September 23, 2018 • 7:00 p.m. Qty. # $ SUPERSTAR: The Songs, The Stories, The Carpenters $35 Thursday, October 11, 2018 • 7:30 p.m. Qty. # $ The Jerry Schmitt Band $15 Thursday, November 8, 2018 • 7:30 p.m. Qty. # $ Premium Seating (first 4 rows) Reserved Seating The Doo Wop Project $57 $47 Saturday, December 8, 2018 • 7:30 p.m. Qty. # $ The Siegmann Family $15 Sunday, January 27, 2019 • 2:00 p.m. Qty. # $ Gina Chavez $25 Saturday, February 9, 2019 • 7:30 p.m. Qty. # $ Premium Seating (first 4 rows) Reserved Seating The High Kings $45 $35 Thursday, March 14, 2019 • 7:30 p.m. Qty. # $ Subtotal = $ Season Tickets: Pick 6 or more LuCille’s Vision Series performances and save 10%. –10% = $ Total LuCille’s Vision Series = $ Our Front Porch Series Adult *Youth Total # Total $ Seating Preference Joseph & the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat $12 $5 Friday, November 2, 2018 • 7:30 p.m. -

E John Stover SWIC PD in Memory

Desk Log INTERNATIONAL POLICE ASSOCIATION R57 - SOUTHERN ILLINOIS www.ipa-usa.org/region57 A Quarterly Newsletter Volume 17, Issue 4 Oct/Nov/Dec 2015 Region 57 Counties Alexander, Bond, Clay, Clinton, Crawford, Edwards, Effingham, Fayette, Franklin, Gallatin, Hamilton, Hardin, Jackson, Jasper, Jefferson, Johnson, Lawrence, Madison, Marion, Massac, Monroe, Perry, Pope, Pulaski, Randolph, Richland, St. Clair, Saline, Union, Wabash, Washington, Wayne, White and Williamson. COUNTRIES OF THE IPA REGION 57 REGION 57 OFFICERS Andorra, Argentina, Armenia, Where the Mother Road Rt. 66 the President/Editor Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia & National Road Rt 40 , Kevin Gordon Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, the Loneliest Road Rt 50 [email protected] Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, and the Great River Road cross. Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, 1st Vice-President Finland, France, Germany, Gibraltar, OFFICIAL ADDRESS Kevin McGinnis Greece, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, PO Box 7 Mascoutah, IL 62258 [email protected] Kenya, Latvia, Lesotho, Lithuania, www.ipa-usa.org/region57 Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malta, [email protected] 2nd Vice-President Mauritius, Mexico, Molova, Monaco, Roger McLean Montenegro, Mozambique, Desk Log is published 4x a year. [email protected] Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, 1st Quarter Jan-Feb-Mar Pakistan, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Secretary/Treasurer Submission by Dec. 15 Romania, Russia, San Marino, Serbia, Patti McDaniel Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, 2nd Quarter Apr -May-June [email protected] Sri Lanka, Surinam, Swaziland, Submission by March 15 Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States. 3rd Quarter Jul-Aug-Sep Submission by June 15 US Section Officers 4th Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec Submission by Sep 15 Region offices are for 3 years. -

2019 Ashes Series Tour Brochure

2019 Ashes Series Tour Brochure July - August - September 2019 1 2019 Ashes Series Tour Brochure Dear Cricket Fans, AST are excited to present our Tour Preview for the 2019 Ashes Series. We invite you to explore our fantastic range of escorted Test tours! Highly Anticipated Series Thanks to the ever-growing interest in cricket’s longest standing rivalry, plus a welcome return to its traditional four-year cycle following back-to-back away series in 2013 & 2015, the 2019 Ashes Series has generated more pre- registered interest than we’ve ever experienced. Whether you’re planning your first ever Ashes series in England or returning to do it all over again, there truly is no other experience that even comes close to the battle for the Urn on English soil. Limited Availability Based on the overwhelming level of interest we’ve received for 2019, we have limited availability remaining on all our tours. As such, we strongly encourage you to explore this brochure, refer to our website for full & finalized details and be ready to secure your place with a $1,000 deposit as soon as possible. Tour Prices Prices listed are based on twin share accommodation, with single supplement upgrade also available to add at time of booking. The earlier you book the better! CATO2019/930 - Australian Sports Tours, a Cricket Australia Come & Join Us Travel Off ice Licensed Travel Operator for the 2019 Ashes Series As the most experienced cricket tour operator in our field, our tours feature The Cricket Australia shield device is a trade mark of, and used everything you would expect from a first class touring experience. -

Cavern Coach Trip 13/3/17

Cavern Coach Trip 13/3/17 COACH 1 CAVERN TRIP 13/3/2017 From - To : Time First Name Surname R Notes 1 Gail Attenbourgh 2 Phil Beatty Return Staff 3 Anthony Jones Return Staff 4 Olly Sansom Return Staff 5 Toby Smith Staff 6 Annette Whitehouse Staff 7 Tom Whitehouse Return Staff 8 Michael Anthony 9 Tammy Aslam 10 Tammy Aslam 11 Louise Barnes 12 Jayne Buxton 13 Jayne Buxton 14 Emma Clarke 15 Emma Clarke 16 Emma Clarke 17 Emma Clarke 18 Ann Colloby 19 Ann Colloby 20 Ann Colloby 21 Neil Creaton 22 Neil Creaton 23 Neil Creaton 24 Neil Creaton 25 Lorraine Currran 26 Lorraine Currran 27 Lorraine Currran 28 Catherine Davison 29 Catherine Davison 30 Stephen Davis 31 Stephen Davis 32 Stephen Davis 33 Dmitriy Dolgikh 34 S Duffy 35 S Duffy 36 Sally Farr 37 Sally Farr 38 Ian Fry 39 Ian Fry 40 Tom Garner 41 Carol Glenn 42 Emma Guest 43 Emma Guest 44 Emma Guest 45 Helen Hodgson 46 Helen Hodgson 47 Helen Hodgson 48 Helen Hodgson 49 Ms Jeynes 50 Ms Jeynes 51 C Kerrigan 52 C Kerrigan 53 K Kingston Cavern Coach Trip 13/3/17 COACH 2 CAVERN TRIP 13/3/17 From - To : Time First Name Surname R Notes 1 Juliette Patterson 2 Bobby Patterson 3 Phil Collier 4 Mark Webb 5 Charlie Nolan 6 Evonne Augustine 7 J Evans 8 M Fallon 9 Sandra Farmer 10 Sandra Farmer 11 Dom Handy 12 Michelle Harris 13 Michelle Harris 14 Josephine Harrison 15 Imogen Keddie 16 Imogen Keddie 17 Natasha Maidment 18 Natasha Maidment 19 Joanne Macbean 20 Joanne Macbean 21 Samantha Mannion 22 Ros Mason 23 Ros Mason 24 Jamie McLachlan 25 Karen Moore 26 Karen Moore 27 Darren Moore 28 Darren Moore 29 Joshua Naylor 30 B Norris 31 Daxa Patel 32 Daxa Patel 33 M Peplow 34 B Picken 35 Ian Ryan 36 Ian Ryan 37 Ian Ryan 38 J Saunders 39 Alison Screti 40 Sarah Tucker 41 Sarah Tucker 42 Sarah Tucker 43 Sarah Tucker 44 Josephine Smith 45 Joy Sweatman 46 Joy Sweatman 47 Suzy Taylor 48 Suzy Taylor 49 Maggie Wales 50 Maggie Wales 51 Linda Ward 52 J Weir 53 Andrew Welch Cavern Coach Trip 13/3/17 COACH 3 From - To : Time First Name Surname R Notes Cavern Coach Trip 13/3/17 COACH 4 From - To : Time First Name Surname R Notes 1 STAFF 2 STAFF 3 4. -

Kurdějov (Czech Republic) June 13-15, 2018 Publisher

XXI. MEZINÁRODNÍ KOLOKVIUM O REGIONÁLNÍCH VĚDÁCH. SBORNÍK PŘÍSPĚVKŮ. 21 ST INTERNATIONAL COLLOQUIUM ON REGIONAL SCIENCES. CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS. Place: Kurd ějov (Czech Republic) June 13-15, 2018 Publisher: Masarykova univerzita, Brno Edited by: Viktorie KLÍMOVÁ Vladimír ŽÍTEK (Masarykova univerzita / Masaryk University, Czech Republic) Vzor citace / Citation example: AUTOR, A. Název článku. In Klímová, V., Žítek, V. (eds.) XXI. mezinárodní kolokvium o regionálních vědách. Sborník příspěvků. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, 2018. s. 1–5. ISBN 978-80-210-8969-3. AUTHOR, A. Title of paper. In Klímová, V., Žítek, V. (eds.) 21 st International Colloquium on Regional Sciences. Conference Proceedings. Brno: Masarykova univerzita, 2018. pp. 1– 5. ISBN 978-80-210-8969-3. Publikace neprošla jazykovou úpravou. / Publication is not a subject of language check. Za správnost obsahu a originalitu výzkumu zodpovídají autoři. / Authors are fully responsible for the content and originality of the articles. © 2018 Masarykova univerzita ISBN 978-80-210-8969-3 ISBN 978-80-210-8970-9 (online : pdf) Sborník p řísp ěvk ů XXI. mezinárodní kolokvium o regionálních v ědách Kurd ějov 13.–15. 6. 2018 DOI: 10.5817/CZ.MUNI.P210-8970-2018-63 ‘DISCOVER CENTRAL EUROPE’ – PROMOTION OF THE VISEGRAD GROUP’S CROSS-BORDER TOURIST PRODUCTS TOMASZ STUDZIENIECKI 1 BEATA MEYER 2 MARZENA WANAGOS 1 1Department of Economics of Services Faculty of Entrepreneurship and Commodity Science Gdynia Maritime University Ul. Morska 81-87, 81-225 Gdynia, Poland, E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2Department of Tourism Management Faculty of Management and Economics of Services University of Szczecin Ul. Cukrowa 8, 71-004 Szczecin, Poland E-mail: [email protected] Annotation This paper raises the issue of branding cross-border destinations. -

September 2014 October November December January 2015 February

September 2014 12 Indoor Meeting: The Swift Conservation Trust by Edward Mayer 11 Indoor Meeting: AGM and Wild West Birding by David Cromack, Start: 22 Coach Trip: Elmley Marshes RSPB 7:30pm Reserve 14 Car Trip: Holland Haven, Meet at car March park, 9:30am – TM 220 160 12 Indoor Meeting: The BTO Bird Atlas 28 Coach Trip: Cley Marshes, Norfolk 2007-2011 by Dawn Balmer October 22 Car Trip: Cavenham Heath, Meet at reserve car park (turn right in 9 Indoor Meeting: Birds of the Tuddenham village), 9:30am – TL 745 Camargue by Jonathan Forgham 721 12 Car Trip: Alresford Creek, Park at the 30 Coach Trip: Holkham Nature Reserve, 29 Coach Trip: The Lodge and Grafham old church, 9:30am – TM 063 197 Norfolk Water 26 Coach Trip: Holme next the Sea and December April Titchwell RSPB Reserve 7 Car Trip: Tollesbury Wick, Meet at car 9 Indoor Meeting and Cake Bake: November park, Woodrolf Road, 9:30am – TM 157 Wings and Things of Scotland by 352 9 Car Trip: Lower Holbrook, Meet at car Richard Pople 11 Indoor Meeting and Christmas Party: park, 9:30am – TM 177 351 12 Car Trip: RSPB Boyton Marshes, Meet Birds of East Anglia by Bill Baston 13 Indoor Meeting: Birds of Southern at reserve car park, 9:30am – TM 386 Europe: Spain and Hungary by Bill January 2015 475 Coster 4 Car Trip: East Mersea, Meet at car park in Bromans Lane, 9:30am – TM 067 147 8 Topsy Agnew Lecture: Birds of South India and Sri Lanka by Dr Simon Cox 25 Coach Trip: Rainham Marsh RSPB Reserve February 8 Car Trip: Rolls Farm, Meet at old barn Prentice Hall Lane, 9:30am – TL 944 095 26 Coach Trip: Pulborough Brooks RSPB Indoor meetings start at 7:45pm (unless Reserve otherwise stated) and are held at the Shrub End Community Hall opposite the May Leather Bottle public house in Shrub End 13 Car Trip (Wednesday): Minsmere 100 Road, Colchester. -

Common Law Division Supreme Court New South Wales

Common Law Division Supreme Court New South Wales Case Name: Moore v Scenic Tours Pty Limited (No.2) Medium Neutral Citation: [2017] NSWSC 733 Hearing Date(s): 26, 27, 28 April 2016, 11, 12, 13 May 2016 Date of Orders: 31 August 2017 Date of Decision: 31 August 2017 Jurisdiction: Civil Before: Garling J Decision: See [946] Catchwords: CONSUMER LAW – all-inclusive five-star luxury cruise along European rivers – where cruise substantially disrupted by flooding – whether breach of consumer guarantees CONSUMER LAW – meaning of “services” in particular factual context – whether breach a result of a cause independent of human control STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION –– whether Civil Liability Act (‘CLA’) picked up by s 80 Judiciary Act DAMAGES – compensation for reduction in value – assessment – whether amount recovered through insurance policy to be subtracted from total of compensation awardable STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION – damages for distress and disappointment – whether Pt 2 CLA applied by s 275 Australian Consumer Law – whether damages “personal injury” under Pt 2 CLA – whether damages meet Pt 2 CLA threshold – whether CLA operates extra-territorially DAMAGES – assessment – damages for distress and disappointment CONTRACTS – construction – whether terms and conditions permitted significant variation of itinerary Legislation Cited: Australian Consumer Law Civil Liability Act 2002 Civil Procedure Act 2009 1 Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) Contracts Review Act 1980 Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) Social Security Act 1991 (Cth) Supreme Court Act 1970 -

Czech Republic Austria & Hungary #1

Czech Republic Austria & Hungary Sports Tour Prague, Vienna & Budapest 11 Day / 9 Night Program www.victorysportstours.com SUGGESTED PROGRAM PLEASE NOTE: Actual sequence and timing of activities will revolve around your game & practice schedule, which will be finalized in the weeks prior to your team’s arrival at its destination. All times are approximate and may vary according to flight schedules and other logistical factors. ALL SPORTS ACTIVITIES ARE HIGHLIGHTED IN RED. Day 1 USA – PRAGUE Evening Depart USA on your overnight flight to Prague. Possible change of plane enroute. Dinner and breakfast served aloft. Day 2 PRAGUE Morning Arrive in Prague. Greeting by your highly-qualified Tour Manager. The Tour Managers we select are chosen for their high-energy and commitment to customer satisfaction. For the duration of your stay, your Tour Manager will be coordinating and managing all of your scheduled activities and will be available to you on a 24-hour basis should you need special assistance. Prague is one of Europe’s most historic cities and popular tourist destinations. The city’s centuries-old architectural landmarks are largely untouched and unspoiled, almost giving the city the feel of a giant museum waiting to be explored with many treasures to be discovered. Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque and neoclassical-style buildings and monuments are mixed in with newer architectural styles, such as art nouveau and cubist, making for an engaging visual feast. Transfer by private motorcoach to your Three-Star Hotel for check-in. Afternoon Free time to explore the neighborhood around your hotel and have lunch on your own. -

Stays, Excursions and Tours Metz Métropole and Its Region

2021 STAYS, EXCURSIONS AND TOURS METZ MÉTROPOLE AND ITS REGION 1 YOUR CONTACT Reception Service METZ MÉTROPOLE Phone: +33 (0)3 87 39 01 02 Fax: +33 (0)3 87 36 59 43 [email protected] ACCESS KEY Metz is ideally served by motorways (A4 and A31), TGV train FIGURES services (Metz-Ville and Lorraine TGV Station) and the nearby airports of Metz-Nancy, Luxembourg and Saarbrücken. By TGV, Metz is just 82 minutes from Paris, 71 minutes from 230,000 Roissy Charles-de-Gaulle, and 50 minutes from Strasbourg. inhabitants (Metz Métropole) 895,465 overnight stays (Metz Métropole, 2019) 304,000 visitors to the Centre Pompidou-Metz (2019) 52 m² of green space for every inhabitant over 80 km of cycle paths 3 stars in the Michelin Green Guide Metz is one of the top 20 destinations to visit in 2020 according to Condé Nast Traveller Metz Christmas Markets came th 7 in the competition Best Christmas Markets in Europe 2020 COACH PARKING MAP Downloadable from your group space at: www.tourisme-metz.com/fr/plan-et-stationnement-de-bus.html 2 YOUR CONTACT Reception Service METZ MÉTROPOLE Phone: +33 (0)3 87 39 01 02 Fax: +33 (0)3 87 36 59 43 [email protected] ART & TECH CELEBRATING THE CATHEDRAL’S 800TH ANNIVERSARY! From Gallo-Roman times to the present Metz, the capital of urban ecology at the day, Metz is a mosaic of colours, styles confluence of the Moselle and the Seille, Carol and her team are ready to and materials. Essentially Roman but with is easy to explore on foot or by bike. -

Oxford Coach Trip Booking Form Oxford Trip Sunday 21 August - Booking Form

Southampton Group Ramblers' Association – Oxford Coach Trip Booking Form Oxford Trip Sunday 21 August - Booking Form Please book give names & pick up points: 08.00 Bitterne Sainsbury’s; 08.15 Southampton Central Station, Blechynden Terrace; 08.30 Totton bus stop opposite Lloyds Bank; 08.45 Hockley Viaduct layby. Only £10 per person. (See conditions below and Newsletter for trip details.). Please put your name(s) in the box of your choice and your morning pick-up location. Options Names Morning Pick-Up 1. Joining the moderate 9.5 mile circular walk starting & finishing in Woodstock 2. Just visiting Blenheim Palace - Woodstock 3. Joining the leisurely 6 mile walk around Oxford city with time in Oxford afterwards. 4. Just visiting Oxford. I enclose a cheque for £………… payable to Southampton Ramblers Association. Contact Telephone no. ……………………………… (Landline number please where available, not mobile.) Email or home address................................................................................................................................ ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... Print more copies of form for additional persons. Please send the whole completed form (with a SAE, if no email address) and cheque to John Catchlove, Flat 16 Beaulieu Court, 35 Winn Road, Southampton, SO17 1EL by 12 August 2016. Enquiries to 023 8055 3883 - mobile on the day 07907 942780. * Conditions. To ensure that the series is viable we need to receive sufficient advance bookings by 12 August. Places will be allocated on a first come first served basis. There may be no seats available for non pre-booked persons. Cheques will not be cashed until sufficient bookings have come in for the series to be viable. In the event of cancellation due to insufficient support cheques will be returned. -

A Disastrous Coach Trip Creative Writing Session With

A disastrous coach trip creative writing session with Listen to Matt Brown read the below extracts and introduce the task here: https://youtu.be/kMyUU67cLE0 Extract from Mutant Zombies Cursed My School Trip! Packing the bag “Well thanks very much for interrupting,” he said. “We were actually just about to begin an exciting acting project. And now you’ve barged in like a stupid great big blundering pile of dog plops and spoiled it all. AGAIN!” He walked over to Ian’s mum, who had no idea he was there, picked his nose and smeared a trail of silvery snot right down the side of her face. Ian sniggered and Remington Furious III disappeared in a triumphant puff of smoke. “Now then,” said Ian’s mum, who couldn’t feel the snot trail because that was also part of Ian’s imagination. “Shall we pack alphabetically or by body zone?” “Mum, the school trip isn’t until Tuesday. Do we really have to do this now?” Ian’s mum stopped sorting through socks and looked at him. She had a strange faraway look on her face. A bit like the sort of face Ian made when he went for a secret wee in the sea. “It’s the very first time you’ve ever spent a night away from home,” she said. “How on earth are you going to cope without your mummy to look after you?” She paused for a moment. “It’s not too late to change your mind, you know? You could back out if you wanted and stay here with me.” Ian sighed.