University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F!13Il-.-.; A:: It: Identification of Littoral Cells

Journal of Coastal Research 381-400 Fort Lauderdale, Florida Spring 1995 Littoral Cell Definition and Budgets for Central Southern England Malcolm J. Bray, David J. Carter and Janet M. Hooke Department of Geography University of Portsmouth Portsmouth, POI 3HE, England ABSTRACT . BRAY, M.J.; CARTER, D.J., and HOOKE, J.M., 1995. Littoral cell definition and budgets for central southern England. Journal of Coastal Research, 11(2),381-400. Fort Lauderdale (Florida), ISSN 0749 ,tllllllll,.e 0208. Differentiation of natural process units is promoted as a means of better understanding the interconnected . ~ ~ - nature of coastal systems at various scales. This paper presents a new holistic methodology for the f!13Il-.-.; a:: it: identification of littoral cells. Testing is undertaken through application to an extensive region of central ... bJLt southern England. Diverse sources of information are compiled to map 8. detailed series of local sediment circulations both at the shoreline and in the offshore zone. Cells and sub-cells are subsequently defined by thorough examination of the continuity of sediment transport pathways and by identification of boundaries where there are discontinuities. Important distinctions are made between the nature and stability of different boundaries and a classification of types is devised. Application of sediment budget analysis to major process units helps to clarify the regional significance of different sediment sources, stores and sinks. Within the study area, it is shown that sediments circulate from distinct eroding cliff sources to well defined sinks. Natural beaches are transient and dependent upon the continued functioning of supply pathways from cliff sources. Relict cells with residual circulations are identified as a consequence of interference. -

Community Infrastructure Levy

WINCHESTER CITY COUNCIL COMMUNITY INFRASTRUCTURE LEVY INFRASTRUCTURE STATEMENT July 2013 Infrastructure Statement Introduction The Community Infrastructure Levy Regulations 2010 (as amended) require the City Council to submit “copies of the relevant evidence” to the examiner. The purpose of this statement is to set out the City Council’s evidence with regard to the demonstration of an infrastructure funding gap, confirmation of the Council’s spending priorities (the draft list), and clarification of its approach in respect of S106 contributions. The City Council is also seeking to comply with the Government’s Community Infrastructure Levy Guidance (April 2013) which sets out the more detailed requirements in respect of the funding gap at paragraphs 12 -14, and of the prioritisation and funding of infrastructure at paragraphs at 84 - 91. In respect of the latter, the principal aim of this statement is to provide transparency on what the Council, as a charging authority, intends to fund in whole or in part through the levy, and those known matters where S106 contributions may continue to be sought (CIL Guidance, paragraph 15). Infrastructure Funding Gap The Government’s CIL Guidance states: • “A charging authority needs to identify the total cost of infrastructure that it desires to fund in whole or in part from the levy” (paragraph 12); • “Information on the charging authority area’s infrastructure needs should be directly related to the infrastructure assessment that underpins their relevant plan.” (paragraph. 13); • “In determining the size of its total or aggregate infrastructure funding gap, the charging authority should consider known and expected infrastructure costs and the other sources of possible funding available to meet those costs.” (paragraph 14). -

The Stately Homes of England

The Stately Homes of England Burghley House…Lincolnshire The Stately Homes of England, How beautiful they stand, To prove the Upper Classes, Have still the Upper Hand. Noel Coward Those comfortably padded lunatic asylums which are known, euphemistically, as the Stately Homes of England Virginia Woolf The development of the Stately home. What are the origins of the ‘Stately Home’ ? Who acquired the land to build them? Why build a formidable house? What purpose did they signify? Defining a Stately House or Home A large and impressive house that is occupied or was formerly occupied by an aristocratic family Kenwood House Hampstead Heath Upstairs, Downstairs…..A life of privilege and servitude There are over 500 Stages of evolution Fortified manor houses 11th -----15th C. Renaissance – 16th— early 17thC. Tudor Dynasty Jacobean –17th C. Stuart Dynasty Palladian –Mid 17th C. Stuart Dynasty Baroque Style—17th—18th C. Rococo Style or late Baroque --early to late 18thC. Neoclassical Style –Mid 18th C. Regency—Georgian Dynasty—Early 19th C. Victorian Gothic and Arts and Crafts – 19th—early 20th C. Modernism—20th C. This is our vision of a Stately Home Armour Weapons Library Robert Adam fireplaces, crystal chandeliers. But…… This is an ordinary terraced house Why are we fascinated By these mansions ? Is it the history and fabulous wealth?? Is it our voyeuristic tendencies ? Is it a sense of jealousy ,or a sense of belonging to a culture? Where did it all begin? A basic construction using willow and ash poles C. 450 A.D. A Celtic Chief’s Round House Wattle and daub walls, reed thatch More elaborate building materials and upper floor. -

Initial Proposals for New Parliamentary Constituency Boundaries in the South East Region Contents

Initial proposals for new Parliamentary constituency boundaries in the South East region Contents Summary 3 1 What is the Boundary Commission for England? 5 2 Background to the 2018 Review 7 3 Initial proposals for the South East region 11 Initial proposals for the Berkshire sub-region 12 Initial proposals for the Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, 13 Kent, and Medway sub-region Initial proposals for the West Sussex sub-region 16 Initial proposals for the Buckinghamshire 17 and Milton Keynes sub-region Initial proposals for the Hampshire, Portsmouth 18 and Southampton sub-region Initial proposals for the Isle of Wight sub-region 20 Initial proposals for the Oxfordshire sub-region 20 Initial proposals for the Surrey sub-region 21 4 How to have your say 23 Annex A: Initial proposals for constituencies, 27 including wards and electorates Glossary 53 Initial proposals for new Parliamentary constituency boundaries in the South East region 1 Summary Who we are and what we do Our proposals leave 15 of the 84 existing constituencies unchanged. We propose The Boundary Commission for England only minor changes to a further 47 is an independent and impartial constituencies, with two wards or fewer non -departmental public body which is altered from the existing constituencies. responsible for reviewing Parliamentary constituency boundaries in England. The rules that we work to state that we must allocate two constituencies to the Isle The 2018 Review of Wight. Neither of these constituencies is required to have an electorate that is within We have the task of periodically reviewing the requirements on electoral size set out the boundaries of all the Parliamentary in the rules. -

Memorandum of Understanding 2013

MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING Agreed on 28th June 2013. The parties to this memorandum of understanding (MoU) are: (1) BASINGSTOKE AND DEANE BOROUGH COUNCIL of Civic Offices, London Road, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 4AH; (2) EAST HAMPSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL of Penns Place, Petersfield, Hampshire GU31 4EX; (3) EASTLEIGH BOROUGH COUNCIL of Civic Offices, Leigh Road, Eastleigh, Hampshire SO50 9YN; (4) FAREHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL of Civic Offices, Civic Way, Fareham, Hampshire PO16 7AZ;1 (5) GOSPORT BOROUGH COUNCIL of Town Hall, High Street, Gosport, Hampshire PO12 1EB; (6) HAMPSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL of The Castle, Winchester, Hampshire, SO23 8UJ; (7) HART DISTRICT COUNCIL of Civic Offices, Harlington Way, Fleet, Hampshire GU51 4AE; (8) COUNCIL OF THE BOROUGH OF HAVANT of Public Service Plaza, Civic Centre Road, Havant, Hampshire PO9 2AX; (9) NEW FOREST DISTRICT COUNCIL of Appletree Court, Lyndhurst Hampshire SO43 7PA; (10) NEW FOREST NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY of Avenue Road, Lymington SO41 9ZG: (11) RUSHMOOR BOROUGH COUNCIL of Council Offices, Farnborough Road, Farnborough, Hampshire GU14 7JU; (12) TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL of Beech Hurst, Weyhill Road, Andover, Hampshire, SP10 3AJ; (13) WINCHESTER CITY COUNCIL of City Offices, Colebrook Street, Winchester, Hampshire SO23 9LJ. 1 Fareham Borough Council accepts this MoU as a guide for development in all areas of Fareham Borough other than Welborne which, due to its complexities, requires a separate agreement with the County Council. CONTENTS CLAUSE 1. PURPOSE............................................................................................................. -

Foundation Document- Stage 1 Towards the SEMS Management Scheme

February 2002 (amended Feb & July 2002) i February 2002 (amended Feb & July 2002) ii Solent European Marine Sites Foundation Document- Stage 1 towards the SEMS Management Scheme. Compiled by: Rachael Bayliss February 2002 (Updated February 2002) (Updated July 2003) Cover photographs: ã Hampshire County Council & Solent Forum ISBN 1 85975 534 8 February 2002 (amended Feb & July 2002) iii February 2002 (amended Feb & July 2002) iv Contents 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 Legislative Background 3 2.1 The Habitats and Birds Directives and the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance 2.2 The Habitats Regulations 1994 2.3 Competent and Relevant Authorities 2.4 Management Scheme 2.5 English Nature’s Role 3.0 European Marine Sites in the Solent 7 3.1 European Marine Sites 3.2 Special Areas of Conservation within the SEMS 3.3 Special Protection Areas and Ramsar sites within the SEMS 3.4 Solent European Marine Sites 3.5 Other Designations Adjacent to the SEMS 4.0 Management Structure 17 4.1 Relevant Authorities in the Solent 4.2 SEMS Management Group 4.3 SEMS Strategic Advisory Group 4.4 SEMS Project Officer 4.5 Cluster Groups 4.6 Other groups 4.7 Relationship with Other Coastal Initiatives 4.7.1 Links to the Solent Forum 4.7.2 Links to other groups/initiatives 5.0 English Nature’s Regulation 33 Advice 23 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Conservation Objectives 5.3 Favourable Condition Table and Monitoring 5.4 Operations 6.0 Plans & Projects 27 6.1 Determination of Significant Effect 6.2 Appropriate Assessment 7.0 SEMS Management Scheme 29 7.1 Introduction -

3797-Oakeley-Vale-Brochure-Digital

OAKELEY VALE, PROVIDENCE HILL, BURSLEDON WELCOME TO OAKELEY VALE WE ARE PROUD TO PRESENT OUR LATEST COLLECTION OF TRADITIONAL 3, 4 AND 5 BEDROOM FAMILY HOMES, IN THE WELL-CONNECTED VILLAGE OF BURSLEDON. Nestled in a prime, family friendly location just Outdoor fun is close at hand with a specially 15 minutes from Southampton, Oakeley Vale is designed play area and play trail that will keep perfectly positioned to enjoy the spoils of the the kids (and the young at heart!) occupied Hampshire coastline and countryside whilst for hours. offering easy access to the motorway and local Venture outside of your front door and you’ll commuter routes. find everything you need for everyday life. Local Thoughtfully arranged around large areas of open shops, schools for all age groups, recreational green space, the homes at Oakeley Vale benefit and leisure facilities at Holly Hill Leisure Centre, from a close relationship with nature. A raised offering regular classes and family events, and boardwalk over a small natural stream provides a convenient 24-hour supermarket with petrol an enchanting nature walk, with convenient station. There really is something for everyone. seating and a viewing deck well placed for enjoying the wildlife. 2 3 OAKELEY VALE, PROVIDENCE HILL, BURSLEDON LOCAL ADVENTURES RIGHT ON YOUR DOORSTEP LOOKING FOR A DAY OUT? BURSLEDON AND THE SURROUNDING LOCAL AREA HAVE ALL YOUR NEEDS CATERED FOR. FROM THE ADVENTUROUS TO THE SEDATE, YOU’LL FIND IT ALL IN HAMPSHIRE AND THE NEIGHBOURING COUNTIES. THE QUESTION IS, WHAT TO DO FIRST? Families are spoilt for choice with Manor If retail therapy is what you’re after, look no Farm, part of the River Hamble Country further than Southampton’s Westquay, with Park, just minutes from home offering the floor upon floor of high street favourites and opportunity to get up close to the animals convenient tasty restaurants ready to refuel and watch them grow. -

SUSSEX INDUSTRIAL Material for Both the Newsletter and Sussex Industrial History Is Always Welcome

A NOTE TO CONTRIBUTORS SUSSEX INDUSTRIAL Material for both the Newsletter and Sussex Industrial History is always welcome. It would ARtHAEOLOCY SOCIEfY however make life easier if Registen!d ClIariIy No. 267159 i. contributions were typed or hand written with plenty of space between the lines. This enables editorial changes, often necessary to ensure a common style between articles, e.g. the way dates are written, to be clearly seen at the word processing stage. NEWSLETTER No. 80 ISSN 0263 516X ii. Members composing articles on their own wordprocessor are invited to submit with the text the disc from Which it is derived to avoid the need to enter the whole article again via Price 25p to non-Members OCTOBER 1993 the keyboard. This can save the Society cost. The editors would much appreciate co-operation in these matters. CHIEF CONTENTS Wealden Sandstone Quarry , ,ilitary /Defence SiteS in ~ussex:- OFFICERS ( I ~ The Ringmer Buffer Depot Underground Rotor Stations in Sussex President A.J. Haselfoot 'Black'lransmitter near Crow borough Chairman Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey, Home Farm, Herons Ghyll, Uckfield News from Amberley Museum Vice Chairman J.5.F. Blackwell, 21 Hythe Road, Brighton BN1 6]R (0273) 557674 Sussex Mills Group News General Sec: R.G. Martin, 42 Falmer Ave, Saltdean, Brighton, BN28FG (0273) 303805 Treasurer & J.M.H. Bevan, 12 Charmandean Rd, WortFiing BN14 9LB (0903) 235421 Membership Sec: PROGRAMME OF ACTIVITIES FOR 1993 Editor B. Austen, 1 Mercedes Cottages, St John's Rd, Haywards Heath RH16 4EH l' (0444) 413845 Saturday 23 October 7.30 p.m Members' evening with several short talks in Drama Room, Archivist P.J. -

Hampshire Ebook.Pmd

Other ebooks in the series Published by: ENGLAND Travel Publishing Ltd Bedfordshire Berkshire Airport Business Centre, 10 Thornbury Road, Buckinghamshire Cambridgeshire Estover, Plymouth PL6 7PP Cheshire Cornwall ISBN13 9781907462160 Cumbria Derbyshire Devon Dorset Durham East Sussex East Yorkshire Essex © Travel Publishing Ltd Gloucestershire Hampshire Herefordshire Hertfordshire Isle of Man Isle of Wight Kent First Published: 1990 Second Edition: 1994 Leicestershire & Rutland Lancashire Third Edition: 1997 Fourth Edition: 1999 Lincolnshire Merseyside & Manchester Fifth Edition: 2001 Sixth Edition: 2003 Norfolk Northamptonshire Seventh Edition: 2005 Eighth Edition: 2009 Northumberland Ninth Edition: 2011 North Yorkshire Nottinghamshire Oxfordshire Shropshire Somerset South Yorkshire Staffordshire Suffolk Please Note: Surrey Tyne and Wear Warwickshire & W Midlands All advertisements in this publication have been accepted in West Sussex good faith by Travel Publishing. West Yorkshire Wiltshire Worcestershire All information is included by the publishers in good faith and WALES is believed to be correct at the time of going to press. No Anglesey and North Coast responsibility can be accepted for errors. North Wales Borderlands Carmarthenshire Ceredigion Editors: Hilary Weston and Jackie Staddon Gower & Heritage Coast Monmouthshire North Powys Pembrokeshire Snowdonia & Lleyn Peninsula Cover Photo: Lymington Quay South Powys © ian badley/ Alamy SCOTLAND Argyll Text Photos: See page 72 Ayrshire & Arran The Borders Dumfries & Galloway Edinburgh and The Lothians Fife Glasgow & West Central This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by Highlands Inner Hebrides way of trade or otherwise be lent, re-sold, hired out, or North East Scotland otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in Orkney and Shetland any form of binding or cover other than that which it is Perthshire, Angus & Kinross published and without similar condition including this Stirling and Clackmannan Western Isles condition being imposed on the subsequent purchase. -

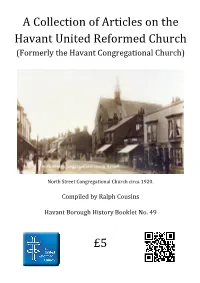

A Collection of Articles on the Havant Reformed Church

A Collection of Articles on the Havant United Reformed Church (Formerly the Havant Congregational Church) North Street Congregational Church circa 1920. Compiled by Ralph Cousins Havant Borough History Booklet No. 49 £5 The Dissenters’ meeting-house was the Independent Chapel in The Pallant 2 Contents A Chapter in the Early History of Havant United Reformed Church John Pile The Revd Thomas Loveder Dissenting Minister of Havant John Pile The Sainsbury Family Connected with Havant United Reformed Church from the Late 1700s Gillian M. Peskett The Revd William Scamp, Protestant Dissenting Minister 1803-1846 Gillian M. Peskett A Brief History of the Dissenters’ Cemetery in New Lane Gillian M. Peskett ‘Loveability, Sympathy and Liberality’: Havant Congregationalists in the Edwardian Era 1901–1914 Roger Ottewill An interesting academic study by Roger at page 68 which gives in depth detail on another aspect of dissent in Havant. 3 North Street Congregational Church circa 1910 4 A Chapter in the Early History of Havant United Reformed Church John Pile Research in any field of enquiry is cumulative and builds upon the efforts of others. Anyone studying the history of Havant United Reformed Church is quickly made aware of the debt owed to Jack Barrett who, as church archivist for many years, was responsible not only for preserving the existing records but for searching out new facts and drawing new conclusions from the material at his disposal. The Reverend Anthony Gardiner came to Havant in 1983 and brought new expertise to bear upon the subject and in 1994 he and Jack collaborated on a revised version of Havant United Reformed Church: a history that Jack had written in 1985. -

PRODUCTION NOTES BBC FILMS and HBO FILMS

PRODUCTION NOTES BBC FILMS and HBO FILMS PRESENT THE SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP 92 minutes SHORT SYNOPSIS Coined by Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the term “special relationship” has come to represent the exceptionally close political, diplomatic, cultural and historical relations between Great Britain and the United States. Some transatlantic alliances have been more potent and more personal than others, among them Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt; John F. Kennedy and Harold Macmillan; Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan; and Tony Blair and Bill Clinton. At least for a time. THE SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP follows Blair’s journey from political understudy waiting in the wings of the world arena to accomplished prime minister standing confidently in the spotlight of center stage. It is a story about relationships, between two powerful men, two powerful couples, and husbands and wives. The time is 1996, and the Blairs and the Clintons are a unique foursome – each of them an extremely bright lawyer – with a kinship forged in shared ideology and genuine affection. When world events and personal watersheds shake the very foundation of their relationship, the men and their wives must come to terms with the ephemeral nature of power and, oftentimes, friendship. As the film begins, there are many similarities between Tony Blair and Bill Clinton, both center-left politicians driven by personal ambition, yet equally driven by a belief they can change the world and do a great deal of good. What starts as the formality of friendship between two national figures evolves into a genuine connection, a meeting of kindred spirits, of ideological soul mates in their domestic agendas. -

—————————————————————————————————————— Site Address

—————————————————————————————————————— Site Address: Land adjacent Woodcroft Primary school, Woodcroft Lane, Waterlooville, PO8 9QD Proposal: Outline application for residential development for 43 residential dwellings with access off Woodcroft Lane and emergency access off Eagle Avenue with all other matters reserved. Application No: APP/15/01235 Expiry Date: 28/01/2016 Applicant: Hampshire County Council Agent: Mr Owen Devine Case Officer: Daphney Haywood Hampshire County Council, Property Services Ward: Hart Plain Reason for Committee Consideration: At Councillor G Shimbart’s request HPS Recommendation: GRANT OUTLINE CONSENT SUBJECT TO A S106 AGREEMENT —————————————————————————————————————— 1 Site Description 1.1 The site, which measures approximately 1.39 hectares and previously formed part of the Woodcroft School site, is located to the north of the Borough of Havant. The County Council applied for and was granted S.77 Consent under the Schools Standards and Framework Act 1998 to dispose of surplus playing field land by the Department of Children, Schools and Families on 05/08/2011. The Milton Road Local Shopping Centre is situated approximately 200 metres to the east while a greater range of shops is available in the Cowplain District Centre located on London Road approximately 1.2 kilometres to the south east. 1.2 Situated to south and west of Woodcroft Primary School, the development site is overlooked by the southern façade of the refurbished school. The School campus itself separates the site from Woodcroft Farm, identified as a Strategic Site in the Havant Borough Local Plan (Core Strategy) 2011. The south-western part of the surplus School land is to be safeguarded for a road access to serve the Strategic Site, which will run from Eagle Avenue.