Tiruchirappalli Shows The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Farmer Database

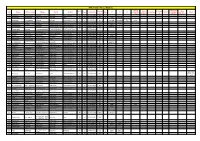

KVK, Trichy - Farmer Database Animal Biofertilier/v Gende Commun Value Mushroo Other S.No Name Fathers name Village Block District Age Contact No Area C1 C2 C3 Husbandry / Honey bee Fish/IFS ermi/organic Others r ity addition m Enterprise IFS farming 1 Subbaiyah Samigounden Kolakudi Thottiyam TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 57 9787932248 BC 2 Manivannan Ekambaram Salaimedu, Kurichi Kulithalai Karur M 58 9787935454 BC 4 Ixora coconut CLUSTERB 3 Duraisamy Venkatasamy Kolakudi Thottiam TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787936175 BC Vegetable groundnut cotton EAN 4 Vairamoorthy Aynan Kurichi Kulithalai Karur M 33 9787936969 bc jasmine ixora 5 subramanian natesan Sirupathur MANACHANALLUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787942777 BC Millet 6 Subramaniyan Thirupatur MANACHANALLUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 42 9787943055 BC Tapioca 7 Saravanadevi Murugan Keelakalkandarkottai THIRUVERAMBUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI F 42 9787948480 SC 8 Natarajan Perumal Kattukottagai UPPILIYAPURAM TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 47 9787960188 BC Coleus 9 Jayanthi Kalimuthu top senkattupatti UPPILIYAPURAM Tiruchirappalli F 41 9787960472 ST 10 Selvam Arunachalam P.K.Agaram Pullampady TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 23 9787964012 MBC Onion 11 Dharmarajan Chellappan Peramangalam LALGUDI TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 68 9787969108 BC sugarcane 12 Sabayarani Lusis prakash Chinthamani Musiri Tiruchirappalli F 49 9788043676 BC Alagiyamanavala 13 Venkataraman alankudimahajanam LALGUDI TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 67 9788046811 BC sugarcane n 14 Vijayababu andhanallur andhanallur TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 30 9788055993 BC 15 Palanivel Thuvakudi THIRUVERAMBUR TIRUCHIRAPPALLI M 65 9788056444 -

Empirical Study on Managerial Factors Involved in Organisational Climate: a Case of Southern Railway, Golden Rock, Tamilnadu

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 10, October 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A EMPIRICAL STUDY ON MANAGERIAL FACTORS INVOLVED IN ORGANISATIONAL CLIMATE: A CASE OF SOUTHERN RAILWAY, GOLDEN ROCK, TAMILNADU M. Monika * Dr. K. Kaliyamurthy** Abstract This study examines the organizational climate – a key factor for the sustainable development of workplace. Organizational climate consists of seven factors namely communication, training and development, teamwork, role and responsibility, work environment, safety measures and human relations. The population of the study consists of employees working in Southern Railway, Golden Rock, Tiruchirappalli. The sample size for the study is 423, by adopting proportionate stratified random sampling technique. Analysis was used to examine the association and significant relationship between selected personal profile of the respondents with organizational climate factors and its inter-relationship in study unit. The organisational climate factors provided by the organization enable employees more committed and contributed to better performance and satisfaction. Communication motivates to work in a challenging work environment. Key factors: Organisational Climate, Communication, Training and Development, Teamwork, Role and Responsibility, Work Environment, Safety Measures and Human Relations. * Ph.D. Research Scholar (FT), Department of Management Studies, Urumu Dhanalakshmi College, Tiruchirappalli – 19, TamilNadu, India ** Head and Associate Professor, Research advisor in Economics and Management, PG & Research Department of Economics, Urumu Dhanalakshmi College, Tiruchirappalli – 19, TamilNadu, India. -

Tamilnadu E-Governance Agency Thiruchirappalli(D)

Tamilnadu e-Governance Agency No. 5/9, TNHB Building,Kavingar Bharathidasan Road, Cresent Street, Alwarpet Chennai - 600 018. Thiruchirappalli(D) - Srirangam(T) Centre Details Centre name Address Revenue details Local bodies details Agency User ID name 1 Amma Mandapam Hope Amma Mandapam, Srirangam, Srirangam(T) Tiruchirappalli(Cor) MIS tri_cor_001 Centre - COR Trichy, - 620006 srirangam firka(F) Srirangam(Z) Mail : [email protected] ANTHANALLUR(RV) 16(W) Phone : 8681033196 2 ULB - Trichy Srirangam Zonal Office Centre, Trichy, - 620006 Srirangam(T) Tiruchirappalli(Cor) ELC tri_elc_ma03,T Corporation - ELCOT Mail : [email protected] srirangam firka(F) Srirangam(Z) NELCTRI009-0 Phone : 9578310794 VELLITHIRUMUTTHAM( 3(W) 1 RV) 3 Maruthandakurichi Maruthandakurichi Panchayat office, Srirangam(T) ANDANALLUR(B) ELC tri_elc_pa01,T Panchayat - ELCOT Kulumani Main Road, Seerathoppu (PO), KULUMANI Firka(F) Kulumani(VP) NELCTRI011-0 Trichy, - 620102 KULUMANI(RV) 1 Mail : [email protected] Phone : 9865283828 4 Punganur Panchayat - Punganur panchyat office, Srirangam(T) ANDANALLUR(B) ELC tri_elc_pa02,T ELCOT Mela street, punganur, Manikandam Firka(F) Puliyur(VP) NELCTRI007-0 Trichy, - 620009 PULIYUR(RV) 1 Mail : [email protected] Phone : 7402613301 5 Natchikurichi Panchayat Natchikurichi Panchayat office, Somarasampettai (PO), Srirangam(T) ANDANALLUR(B) ELC tri_elc_pa03,T - ELCOT Village Panchayat – Natchikurichi, - 620102 Somarasampettai firka(F) Kambarasampettai(VP) NELCTRI004-0 Mail : [email protected] NACHIKURICHI(RV) -

I INTRODUCTION and RESEARCH DESIGN in India As Well As in Most

CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION AND RESEARCH DESIGN In India as well as in most developing countries, the excessive growth of population and the increased trend towards urbanization have led to many things such as haphazard growth of industries, unplanned housing and utility networks, conversion of precious agricultural and forest land into urban land etc. Urban land is one of the important resources provided to man by which necessary human activities are performed. An accurate and uptodate information about the urban land is indispensable for scientific planning and management of urban resources of an area taking into consideration the potentials and the constraints to the environment. The rational planning and management of urban land is possible through the regular survey of the land use which helps in delineating land suitable for various activities. IMPORTANCE OF THE PROBLEM An important feature of urbanization in India is the dualism of urban growth decelerating at macro level. But in Class I cities it is growing. An analysis of the distribution of urban population across size categories reveals that the process of urbanization in India has been large city oriented. This is manifested in a high per centage of urban population being concentrated in 1 class I cities, which has gone up systematically over the decades in the last century. The massive increase in the per centage share of urban population in class I cities from 26.0 in 1901 to 68.7 in 2001 has often been attributed to faster growth of large cities, without taking into consideration the increase in the number of these cities. -

Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu

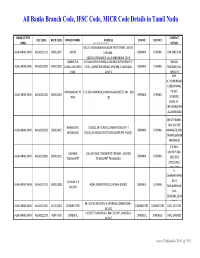

All Banks Branch Code, IFSC Code, MICR Code Details in Tamil Nadu NAME OF THE CONTACT IFSC CODE MICR CODE BRANCH NAME ADDRESS CENTRE DISTRICT BANK www.Padasalai.Net DETAILS NO.19, PADMANABHA NAGAR FIRST STREET, ADYAR, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211103 600010007 ADYAR CHENNAI - CHENNAI CHENNAI 044 24917036 600020,[email protected] AMBATTUR VIJAYALAKSHMIPURAM, 4A MURUGAPPA READY ST. BALRAJ, ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211909 600010012 VIJAYALAKSHMIPU EXTN., AMBATTUR VENKATAPURAM, TAMILNADU CHENNAI CHENNAI SHANKAR,044- RAM 600053 28546272 SHRI. N.CHANDRAMO ULEESWARAN, ANNANAGAR,CHE E-4, 3RD MAIN ROAD,ANNANAGAR (WEST),PIN - 600 PH NO : ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211042 600010004 CHENNAI CHENNAI NNAI 102 26263882, EMAIL ID : CHEANNA@CHE .ALLAHABADBA NK.CO.IN MR.ATHIRAMIL AKU K (CHIEF BANGALORE 1540/22,39 E-CROSS,22 MAIN ROAD,4TH T ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211819 560010005 CHENNAI CHENNAI MANAGER), MR. JAYANAGAR BLOCK,JAYANAGAR DIST-BANGLAORE,PIN- 560041 SWAINE(SENIOR MANAGER) C N RAVI, CHENNAI 144 GA ROAD,TONDIARPET CHENNAI - 600 081 MURTHY,044- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211881 600010011 CHENNAI CHENNAI TONDIARPET TONDIARPET TAMILNADU 28522093 /28513081 / 28411083 S. SWAMINATHAN CHENNAI V P ,DR. K. ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0211291 600010008 40/41,MOUNT ROAD,CHENNAI-600002 CHENNAI CHENNAI COLONY TAMINARASAN, 044- 28585641,2854 9262 98, MECRICAR ROAD, R.S.PURAM, COIMBATORE - ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0210384 641010002 COIIMBATORE COIMBATORE COIMBOTORE 0422 2472333 641002 H1/H2 57 MAIN ROAD, RM COLONY , DINDIGUL- ALLAHABAD BANK ALLA0212319 NON MICR DINDIGUL DINDIGUL DINDIGUL -

Geoinformatics for Concentration of Crime Against Women in Tiruchirappalli City, Tamil Nadu

Journal of Information and Computational Science ISSN: 1548-7741 GEOINFORMATICS FOR CONCENTRATION OF CRIME AGAINST WOMEN IN TIRUCHIRAPPALLI CITY, TAMIL NADU. P. Mary Santhi1, S. Balaselvakumar2 K. Kumaraswamy3 1Research Scholar 2Assistant Professor & 3Emeritus Professor 1&2 Department of Geography, Periyar E.V.R. College (Autonomous), Tiruchirappalli – 620 023 3Department of Geography, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli – 620 024 Affiliated to Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli – 620 024 Abstract This paper is an attempt to mapping and analysing the concentration of crimes against women in Tiruchirappalli city for the years 2012 to 2017. The concentration score of crimes against women (rape, dowry death, molestation, kidnapping, cruelty by husband, dowry Prohibition Act 1961 and POCSO Act, 2012) recorded in each of All Women Police Station (AWPS) has been calculated and it reveals that the high concentration of crime rape was recorded in AWPS Golden rock with 1.4%, dowry death in AWPS Srirangam with 3.4%, molestation in AWPS Cantonment with 0.6%, cruelty by husband in AWPS Srirangam with 1.4%, dowry Prohibition Act 1961 cases in AWPS Fort with 1.7% and POCSO Act, 2012 cases in AWPS Golden rock with 1.4%. The low concentration of crime rape and cruelty by husband was recorded in AWPS Srirangam and Golden rock with 0.9% and molestation and kidnapping in AWPS Fort and Cantonment with 0.1 %. Among all four AWPS, the AWPS Golden rock and Srirangam had recorded the maximum concentration of crimes against women when the total crimes in a particular police station were compared to the total crimes in the study area. -

49107-003: Tamil Nadu Urban Flagship Investment Program

Initial Environmental Examination Document Stage: Draft Project Number: 49107-003 May 2018 IND: Tamil Nadu Urban Flagship Investment Program – Tiruchirappalli Underground Sewerage System Prepared by Tiruchirappalli City Corporation of Government of Tamil Nadu for the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 22 December 2017) Currency Unit – Indian rupee (₹) ₹1.00 – $0.0156 $1.00 = ₹64.0300 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ASI – Archaeological Survey of India CMSC – Construction Management and Supervision Consultant CPCB – Central Pollution Control Board CTE – consent to establish CTO – consent to operate EAC – Expert Appraisal Committee EHS – Environmental, Health and Safety EIA – Environmental Impact Assessment EMP – Environmental Management Plan ESS – Environmental and Social Safeguards ESZ – Eco Sensitive Zone GRC – grievance redress committee GRM – grievance redress mechanism GOI – Government of India GoTN – Government of Tamil Nadu IEE – Initial Environmental Examination MOEFCC – Ministry of Environment, -

View Document

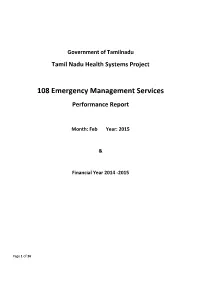

Government of Tamilnadu Tamil Nadu Health Systems Project 108 Emergency Management Services Performance Report Month: Feb Year: 2015 & Financial Year 2014 -2015 Page 1 of 36 Table of Contents Page No 1. Sense - Activities of the Emergency Response Center (ERC) …….......... 3 2. Reach – Ambulance Trip Data………………………………………………….......... 3 3. Life saved Data.................................................................................... 3 4. Care - Emergencies Handled…………………………………………………….......... 3 - 4 5. AN Mother & Neo-natal cases Data .................................................... 4 6. Financial Performance ........................................................................ 5 -6 Annexure: Annexure A: Ambulance Details………………………………………………………... 7 Annexure B: District Wise Distribution of Ambulances…………………….... 8 Annexure C: District Wise Trip Details……………………………………………….. 9 – 10 Annexure D: Hospital Case Admission Details ..................................... 11 Annexure E: District Wise Emergency Cases Handled………………………... 12 - 15 Annexure F: District Wise Kilometre Run & Kilometre / Litre Details... 16 Annexure G: Human Resources Details…………………………………………….. 17 Annexure H: District Wise Hospital MoU Details………………………………. 18 Annexure I: Call and Dispatch Average Handle Time............................ 18-20 Annexure J: Interesting Emergency Cases………………………………………... 21-23 Annexure K: Important Events & Photographs…………………………………. 24 Annexure L: AN Cases Monthly report..……………………………………………. 25 Annexure M: Neonatal ambulance cases............................................. -

23. Ranganatha Mahimai V1

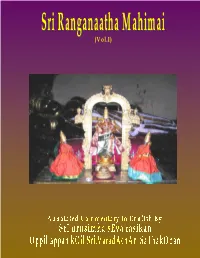

Our Sincere Thanks to the following for their contributions to this ebook: Images contribution: ♦ Sriman Murali Bhattar Swami, www.srirangapankajam.com ♦ Sri B.Senthil Kumar, www.thiruvilliputtur.blogspot.com ♦ Ramanuja Dasargal, www.pbase.com/svami Source Document Compilation: Sri Anil, Smt.Krishnapriya sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Sanskrit & Tamil Paasurams text: Mannargudi Sri. Srinivasan Narayanan eBook assembly: Smt.Gayathri Sridhar, Smt.Jayashree Muralidharan C O N T E N T S Section 1 Sri Ranganatha Mahimai and History 1 Section 2 Revathi - Namperumaan’s thirunakshathiram 37 Section 3 Sri Ranganatha Goda ThirukkalyaNam 45 Section 4 Naama Kusumas of Sri Rnaganatha 87 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org PraNavAkAra Vimanam - Sri Rangam 1 sadagopan.org NamperumAL 2 . ïI>. INTRODUCTION DHYAANA SLOKAM OF SRI RANGANATHA muoe mNdhas< noe cNÔÉas< kre caé c³< suresaipvN*< , Éuj¼e zyn< Éje r¼nawm! hrerNydEv< n mNye n mNye. MukhE mandahAsam nakhE chandrabhAsam karE chAru chakram surEsApivandyam | bhujangE SayAnam bhajE RanganAtham Hareranyadaivam na manyE na manyE || sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org AZHWAR ARULICCHEYALGAL adiyEn will focus here on the 245 paasurams on Sri RanganAthA by the eleven AzhwArs. The individual AzhwAr’s paasurams are as follows: Poygai Mudal ThiruvandhAthi 1 BhUtham Second ThiruvandhAthi 4 PEy Third ThiruvandhAthi 1 Thirumazhisai Naanmukan ThiruvandhAthi 4 Thirucchanda Viruttham 10 NammAzhwAr Thiruviruttham 1 3 Thiruvaimozhi 11 PeriyAzhwAr Periya Thirumozhi 35 ANdAL NaacchiyAr Thirumozhi 10 ThiruppANar AmalanAdhi pirAn 10 Kulasekarar PerumAL Thirumozhi 31 Tondardipodi ThirumAlai 45 ThirupaLLIyezucchi 10 Thirumangai Periya Thirumozhi 58 ThirunedumthAndakam 8 ThirukkurumthAndakam 4 Siriya Thirumadal 1 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Periya Thirumadal 1 Thirumangai leads in the count of Pasurams with 72 to his credit followed by the Ranganatha Pathivrathai (Thondaradipodi) with 55 paasurams. -

NWPE 2008 Individual Academic Institutes Rs.3,000 Dr

Registration Advisory committee NWPE 2008 Individual Academic institutes Rs.3,000 Dr. M. Chidambaram, National Workshop on Power Electronics Industries & Govt. organizations Rs.5,000 Director, NIT, Tiruchirappalli. Students Rs.1,000 Dr. V. K. Aatre, Industry-Institute-R&D Interaction Chairman, National Steering Committee, NaMPET. Group (for 3 Registrations) Academic institutes Rs.8,000 Shri. S. Ramakrishna, Industries & Govt. organizations Rs.12,000 Director General, CDAC. Exhibition Stalls : 10 ft. x 10 ft. : Rs.15,000 Shri. T.K. Sarkar, Sr.Director, DIT, Govt. of India. Two free registrations will be provided for the sponsors of each exhibition stall. Shri. Rajan T Joseph Executive .Director, CDAC, Thiruvananthapuram Sponsorships Organized by Institutional sponsors are invited to support NWPE 2008. Prof. V. Ramanarayanan, IISc, Bangalore. Dept. of Electrical and Electronics Engg., For sponsors contributing Rs.30,000 and above we shall National Institute of Technology, be happy to acknowledge their support in the official Dr. N. Ammasaigounden, Tiruchirappalli. proceedings and all subsequent announcements. Free Dean (IC & SR), NIT, Tiruchirappalli. registration to 3 members of the sponsoring organization th th will also be provided. Registration fees will be accepted Organizing committee 12 – 14 November 2008 only through Demand Draft drawn in favour of “The Director, NIT, Tiruchirappalli” payable at Tiruchirappalli Mrs. K.A. Fathima, CDAC, Thiruvananthapuram (preferably payable at State Bank of India, NIT Branch, Mr. V.S. Suresh Babu, CDAC, Thiruvananthapuram Code:1617). Completed Registration forms Mr. V. Anathakrishnan, BHEL, Tiruchirappalli accompanied by registration fee should reach the Mr. R. Chellapan, Numeric Power Systems, Chennai coordinators not later than 30th September 2008. -

Analytical Study on Em Ployees' Motivation In

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 10, October 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A ANALYTICAL STUDY ON EM PLOYEES’ MOTIVATION IN SOUTHERN RAILWAY, GOLDEN ROCK, TIRUCHIRAPPALLI, TAMIL NADU Ramya. T1 Dr. K. Kaliyamurthy2 ABSTRACT In the workplace, motivation is important to induce an employee to contribute to his maximum capabilities. Every employee has certain unfulfilled desires. The employer, by fulfilling the needs of the employee, motivates him to do his best. To study the level of employee motivation through the financial and non-financial factors acquires significance. When an organization has properly motivated staff, there will be better inter-personal relationships. The schedule was used for collecting data related to study. The sample of the study is 50 employees working in the study area. After the data collection was over, the researcher analyzed the data with the help of Statistical Packages such as SPSS 20 (Statistical Package for Social Science)). The results of the study have indicated that the salary and compensation, achievement motivation, promotional policy, organizational policy, work environment, relationship with superiors, organization facilities have motivated the employees for good performance. 1 Research Scholar, Department of Management studies, Urumu Dhanalakshmi College, Kattur, Tiruchirappalli 2 Associate Professor and Head, Department of Economics, & Research advisor in Management, Urumu Dhanalakshmi College, Kattur, Tiruchirappalli 530 International Journal of Research in Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 1. -

COVID 19 STATUS Total Cases (08.08.2020) 5032 DISCHARGE

TIRUCHIRAPPALLI DISTRICT - COVID 19 STATUS Total Cases (08.08.2020) 5032 DISCHARGE MGM TRICHY 2893 BCCC 215 DISCHARGED FROM HOME ISOLATION (RHQ)) 230 KMC TRICHY 155 SRM TRICHY 88 SINDHUJA TRICHY 68 APOLLO , TRICHY 54 SUNDARAM TRICHY 43 MARUTHI HOSPITAL, TRICHY 42 GVN TRICHY 27 GH KARUR 8 GH PUDUKOTTAI 6 MMM CHENNAI 5 NEURO ONE TRICHY 6 QMED TRICHY 6 STARKIMS TRICHY 5 DHANALAKSMI PERAMBALUR 4 GH NAMAKKAL 4 TMCH TRICHY 4 ESI HOSPITAL, COIMBATORE 3 PANKAJAM TRICHY 3 GH PERAMBALUR 2 JANET HOSPITAL, TRICHY 2 KG HOSPITAL, TANJORE 2 THANGAM NAMAKKAL 2 APOLLO, MADURAI 1 HOTEL THE SCARLET, T.V. KOVIL 2 DHARAN HOSPITAL,SALEM 1 DR.BHUVANESHWARI NURSING HOME 1 GH ARUPPUKOTTAI 1 GH COIMBATORE 1 GH CHIDAMBARAM 1 GH NAGAPATTINAM 1 GH RAJAPALAYAM 1 GH RAMNADU 1 GH SIVAGANGAI 1 GH TANJAVUR 1 GH THENI 1 GH THIRUVARUR 2 GH TIRUNELVELI 1 GH VELLORE 1 KAVERI HOSPITAL, SALEM 1 KMCH, CBE 1 MEENAKSHI MISSION HOSPITAL, MADURAI 1 Navalpattu GH 1 RAMAKRISHNA HOSPITAL, WORAIYUR 1 RANI HOSPITAL, PUDUKOTTAI 1 ROYALPEARL COIMBATORE 1 SRM VADAPALANI 1 SALEMCCC 1 THIRUVERUMBUR GH 1 VADAMALAIYAN MADURAI 1 VELAMMAL MEDICAL COLLEGE, MADURAI 1 TOTAL 3907 TIRUCHIRAPPALLI DISTRICT - COVID 19 STATUS Total Cases (08.08.2020) 5032 ACTIVE ADMISSION MGM TRICHY 309 BCCC 90 KMC TRICHY 92 SRM TRICHY 41 MARUTHI HOSPITAL, TRICHY 41 SINDHUJA TRICHY 22 APOLLO , TRICHY 13 SUNDARAM TRICHY 32 GVN TRICHY 20 GH KARUR 8 SRM HOSPITAL TRICHY 17 RGH TRICHY (RETNA GLOBAL) 11 NEURO ONE TRICHY 9 GH NAMAKKAL 13 VENKATESWARA TV KOIL 7 DHANALAKSMI PERAMBALUR 3 PANKAJAM TRICHY 4 QMED TRICHY 3 RAILWAY