Bongo Flava (Still) Hidden „Underground”1 Rap from Morogoro, Tanzania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Hip-Hop Class

AAAS 135b: GLOBAL HIP-HOP Wed 6:30-9:20 pm Mandel G03 Spring 2012 Wayne Marshall [email protected] office hours: by appointment DESCRIPTION Examining how hip-hop travels and is embraced, represented, and transformed in various locales around the world, this course approaches hip-hop as itself constituted by international flows and as a product and set of practices that circulate globally in complex ways, cast variously as American, African-American, and/or black, and recast through the cultural logics of the new spaces it enters, the soundscapes it permeates. A host of questions arise when we consider hip-hopʼs global scope and significance: What does the genre in its various forms (audio, video, sartorial, gestural) carry beyond the US? What do people bring to it in new local contexts? How are US notions of race and nation mediated by hip-hop's global reach? Why do some global (which is to say, local) hip-hop scenes fasten onto the genre's well-rehearsed focus on place, community, and righteous opposition to structural and representational forms of violence, while others appear more enamored with slick portrayals of hustler archetypes, cool machismo, and ruggedly individualist, conspicuous consumption? How can hip-hop circulate in such contradictory forms? In what ways do hip-hop scenes differ from North to South America, West to East Africa, Europe to Asia? What threads unite them? In pursuit of such questions, we will read across the emerging literature on global hip- hop as we explore the growing resources available via the internet, where websites and blogs, MySpace and YouTube and the like have facilitated a further efflorescence of international (and peer-to-peer) exchanges around hip-hop. -

Contents Audience Insights 2 Campaign Websites 2 Leveraging the National Campaign in Your Community 3

Contents Audience insights 2 Campaign websites 2 Leveraging the national campaign in your community 3 Local communication channels and opportunities 5 Tips for working with media 7 AUDIENCE INSIGHTS Drive Smokefree for Tamariki aims to reach parents, caregivers and whānau who smoke in cars with tamariki present. Ensuring the message resonates with Māori, Pasifika and low- socioeconomic communities who are disproportionately affected by smoking prevalence. Results from the 2018 Youth Insights Survey showed that around 15% of young people were exposed to second hand smoke in cars. CAMPAIGN WEBSITES Campaign Landing Page: The audience facing campaign landing page is www.smokefree.org.nz/drivesmokefreefortamariki It is hosted on the existing smokefree.org website and has been built with our audience in mind for helpful information on how to be smokefree in cars and information on when the law is coming and how those who smoke in cars with kids might be impacted. There is also information on the harm of second hand smoke and why the law has changed. The page has two campaign videos and a link to the Campaign Resources page with downloadable material to help share the message in communities. Campaign Resources Page: This is designed for health promoters and the National Smokefree Cars Working Group and associated community groups hosted by Te Hiringa Hauora | Health Promotion Agency. https://www.hpa.org.nz/campaign/drive-smokefree-for-tamariki This page provides an overview of the National Campaign with links to downloadable materials, logo files, video and radio campaign material that can be used in their local activities to promote Drive Smokefree for Tamariki leading into the law change. -

Suriano.Pmd 113 01/12/2011, 15:11 114 Africa Development, Vol

Africa Development, Vol. XXXVI, Nos 3 & 4, 2011, pp. 113–126 © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, 2011 (ISSN 0850-3907) Hip-Hop and Bongo Flavour Music in Contemporary Tanzania:Youths’ Experiences, Agency, Aspirations and Contradictions1 Maria Suriano* Abnstract The beginning of Tanzanian hip-hop along with a genre known as Bongo Flavour (also Bongo Flava, or Fleva, according to the Swahili spelling), can be traced back to the early 1990s. This music, characterised by the use of Swahili lyrics (with a few English and slang words) is also re- ferred to as the ‘music of the new generation’ (muziki wa kikazi kipya). Without the intention to analyse a complex and multifaceted reality, this article aims to make a sense of this popular music as an overall phenom- enon in contemporary Tanzania. From the premise that music, perform- ance and popular culture can be used as instruments to innovate and produce change, this article argues that Bongo Flavour and hip-hop are not only music genres, but also cultural expressions necessary for the understanding of a substantial part of contemporary Tanzanian youths. The focus here is on young male artists living in urban environments. Résumé Le début du hip-hop en Tanzanie ainsi que d’un genre musical appelé Bongo Flavour (aussi Bongo Flava ou Fleva, selon l’orthographe en Swahili) date du début des années 1990. Caractérisée par l’utilisation de textes en swahili (avec quelques mots en anglais et en argot), cette musique est considérée comme ‘la musique de la nouvelle génération’ (muziki wa kikazi kipya). -

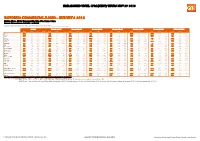

Nz Major Markets Commercial Radio

EMBARGOED UNTIL 1PM (NZDT) THURS NOV 29 2018 NZ MAJOR MARKETS COMMERCIAL RADIO - SURVEY 4 2018 Station Share (%) by Demographic, Mon-Sun 12mn-12mn Survey Comparisons: 3/2018 - 4/2018 This Survey Period: Metro - Sun Jun 24 to Sat Nov 10 2018 / Regional - Sun Jan 28 to Sat Jun 16 2018 & Sun Jun 24 to Sat Nov 10 2018 (Waikato - Sun Aug 21 to Sat Oct 22 2016 & Sun Jan 29 to Sat Jun 17 & Sun Jul 2 to Sat Sep 9 2017) Last Survey Period: Metro - Sun Apr 8 to Sat Jun 16 & Sun Jun 24 to Sat Sep 1 2018 / Regional - Sun Sep 10 to Sat Nov 18 2017 & Sun Jan 28 to Sat Jun 16 2018 & Sun Jun 24 to Sat Sep 1 2018 (Waikato - Sun Aug 21 to Sat Oct 22 2016 & Sun Jan 29 to Sat Jun 17 & Sun Jul 2 to Sat Sep 9 2017) All 10+ People 10-17 People 18-34 People 25-44 People 25-54 People 45-64 People 55-74 MGS with Kids This Last +/- Rank This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- Network Breeze 7.8 8.0 -0.2 3 5.6 6.0 -0.4 5.1 5.1 0.0 7.0 6.3 0.7 7.9 7.6 0.3 9.9 10.1 -0.2 9.7 10.9 -1.2 10.1 8.7 1.4 Network Coast 7.5 7.4 0.1 5 2.3 2.3 0.0 2.1 2.3 -0.2 2.4 2.3 0.1 4.5 4.1 0.4 9.6 10.7 -1.1 14.5 14.8 -0.3 4.3 3.9 0.4 Network The Edge 6.5 6.1 0.4 6 16.2 15.1 1.1 12.0 11.5 0.5 8.7 7.9 0.8 7.1 6.6 0.5 3.5 3.1 0.4 1.7 1.5 0.2 7.2 7.5 -0.3 Network Flava 2.6 2.7 -0.1 14 10.1 10.5 -0.4 4.0 4.9 -0.9 3.0 3.7 -0.7 2.6 2.9 -0.3 1.2 0.8 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 2.5 3.0 -0.5 Network George FM 1.3 1.5 -0.2 17 1.5 2.2 -0.7 2.6 2.7 -0.1 2.6 2.7 -0.1 2.0 2.2 -0.2 0.7 0.9 -0.2 0.2 0.3 -0.1 1.1 1.0 0.1 Network Hokonui 0.2 0.2 0.0 23 0.2 0.3 -

Rotorua Commercial Radio

EMBARGOED UNTIL 1PM (NZDT) THURS NOV 29 2018 ROTORUA COMMERCIAL RADIO - SURVEY 4 2018 Station Share (%) by Demographic, Mon-Sun 12mn-12mn Survey Comparisons: 3/2018 - 4/2018 This Survey Period: Sun Jan 28 to Sat Jun 16 2018 & Sun Jun 24 to Sat Nov 10 2018 Last Survey Period: Sun Sep 10 to Sat Nov 18 2017 & Sun Jan 28 to Sat Jun 16 2018 & Sun Jun 24 to Sat Sep 1 2018 All 10+ People 10-17 People 18-34 People 25-44 People 25-54 People 45-64 People 55-74 MGS with Kids This Last +/- Rank This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- Breeze 8.8 9.3 -0.5 4 5.7 6.2 -0.5 8.8 7.3 1.5 4.8 4.9 -0.1 7.3 8.4 -1.1 13.3 15.8 -2.5 10.5 12.0 -1.5 9.4 10.9 -1.5 Coast 11.5 10.3 1.2 1 0.5 0.6 -0.1 2.2 4.5 -2.3 2.1 4.0 -1.9 6.0 4.7 1.3 16.6 11.3 5.3 24.2 21.0 3.2 3.7 3.6 0.1 Edge 6.8 4.7 2.1 6 10.9 9.7 1.2 18.2 9.8 8.4 10.0 6.6 3.4 9.1 6.4 2.7 4.1 3.2 0.9 0.9 0.9 0.0 8.1 8.9 -0.8 Flava 8.5 8.9 -0.4 5 23.8 24.9 -1.1 16.3 21.6 -5.3 10.7 13.2 -2.5 8.3 10.2 -1.9 2.1 2.2 -0.1 0.6 0.6 0.0 11.3 11.6 -0.3 Life FM 0.6 0.5 0.1 19 1.9 1.9 0.0 0.6 0.6 0.0 1.0 1.0 0.0 0.8 0.8 0.0 0.2 0.2 0.0 * * * 0.4 0.5 -0.1 Magic 6.4 7.4 -1.0 7 1.0 1.1 -0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 1.7 1.9 -0.2 2.2 2.8 -0.6 6.6 7.2 -0.6 13.5 15.6 -2.1 4.1 4.1 0.0 Mai FM 1.8 3.7 -1.9 14 7.2 6.2 1.0 4.3 9.4 -5.1 3.0 8.7 -5.7 2.2 6.4 -4.2 0.3 0.8 -0.5 * * * 1.9 2.6 -0.7 Mix 1.0 0.8 0.2 18 0.1 * * 0.6 * * 2.0 1.7 0.3 1.8 1.6 0.2 1.2 0.9 0.3 0.7 0.2 0.5 0.9 0.8 0.1 More FM 5.0 4.5 0.5 10 5.2 5.8 -0.6 11.6 8.6 3.0 7.7 6.5 1.2 6.3 5.8 0.5 3.0 3.2 -0.2 2.7 2.0 0.7 9.1 -

Imagination and the Practice of Rapping in Dar Es Salaam

David Kerr THUGS AND GANGSTERS: IMAGINAtiON AND THE PRACtiCE OF RAppiNG IN DAR ES SALAAM abstract Since the arrival of hip hop in Tanzania in the 1980s, a diverse and vibrant range of musical genres has developed in Tanzania’s commercial capital, Dar es Salaam. Incorporating rapping, these new musical genres and their associated practices have produced new imaginative spaces, social practices, and identities. In this paper, I argue that rappers have appropriated signs and symbols from the transnational image of hip hop to cast themselves as ‘thugs’ or ‘gangsters’, simultaneously imbuing these symbols with distinctly Tanzanian political conceptions of hard work (kazi ya jasho), justice (haki) and self-reliance (kujitegemea). This article examines how the persona of the rapper acts as a nexus for transnational and local moral and ethical conceptions such as self-reliance, strength, and struggle. Exploring the complicated, ambiguous, and contradictory nature of cultural production in contemporary Tanzania, I argue that rappers use the practice of rapping to negotiate both the socialist past and neo-liberal present. Drawing on the work of De Certeau and Graeber, I argue that rappers use these circulating signs, symbols, and concepts both tactically and strategically to generate value, shape social reality and inscribe themselves into the social and political fabric of everyday life. Keywords: hip hop, popular music, Tanzania, Ujamaa, value INTRODUCTION as well as our individual hopes and ambitions. Octavian and Richard, who as rappers adopt It is mid-morning in June 2011 and I am sat with the names O-Key and Kizito, are both students two ‘underground’ rappers, Octavian Thomas and live close to where we meet. -

Auckland Commercial Radio

EMBARGOED UNTIL 1PM (NZST) THURS SEP 20 2018 AUCKLAND COMMERCIAL RADIO - SURVEY 3 2018 Station Share (%) by Demographic, Mon-Sun 12mn-12mn Survey Comparisons: 2/2018 - 3/2018 This Survey Period: Sun Apr 8 to Sat Jun 16 & Sun Jun 24 to Sat Sep 1 2018 Last Survey Period: Sun Jan 28 to Sat Jun 16 2018 All 10+ People 10-17 People 18-34 People 25-44 People 25-54 People 45-64 People 55-74 MGS with Kids This Last +/- Rank This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- 95bFM 0.8 1.1 -0.3 24 0.6 0.6 0.0 0.9 1.0 -0.1 0.7 1.3 -0.6 0.7 1.1 -0.4 1.3 1.2 0.1 1.3 1.2 0.1 0.6 1.1 -0.5 Ake 0.1 0.1 0.0 29 * * * * * * 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.0 * * * * * * 0.3 0.2 0.1 BBC 0.9 0.8 0.1 22 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.1 0.2 0.4 0.2 0.2 0.6 0.3 0.3 0.8 1.3 -0.5 1.2 1.9 -0.7 0.2 0.2 0.0 Breeze 7.8 8.3 -0.5 4 5.2 7.9 -2.7 4.7 5.6 -0.9 4.6 6.8 -2.2 6.4 7.5 -1.1 10.5 9.9 0.6 12.1 12.3 -0.2 7.8 8.8 -1.0 Chinese Radio AM936 0.9 0.8 0.1 22 0.1 0.8 -0.7 1.4 1.4 0.0 1.6 1.2 0.4 1.4 1.1 0.3 0.7 0.6 0.1 0.5 0.3 0.2 1.0 0.7 0.3 Coast 8.2 8.1 0.1 3 0.9 1.8 -0.9 3.4 1.4 2.0 3.0 3.0 0.0 5.5 4.6 0.9 13.6 11.0 2.6 16.2 15.5 0.7 5.2 4.9 0.3 Edge 4.4 4.4 0.0 8 9.1 10.7 -1.6 7.9 7.5 0.4 5.9 6.0 -0.1 5.1 5.1 0.0 2.7 2.6 0.1 1.1 1.2 -0.1 4.6 5.4 -0.8 Flava 4.9 3.8 1.1 6 19.2 8.9 10.3 8.0 9.5 -1.5 5.9 6.1 -0.2 4.7 4.4 0.3 1.5 0.4 1.1 0.4 0.1 0.3 4.1 3.5 0.6 FM99.4 Chinese Voice 0.5 0.7 -0.2 26 0.2 0.3 -0.1 0.2 0.2 0.0 0.2 0.3 -0.1 0.2 0.6 -0.4 0.7 1.4 -0.7 1.5 1.5 0.0 * * * George FM 2.6 2.1 0.5 13 3.5 2.8 0.7 3.7 3.3 0.4 3.8 3.2 0.6 3.5 2.7 0.8 -

Trace Mziki, the Tv Channel Dedicated to Urban Music from Eastern Africa Launched in French-Speaking Africa with Canal + Afrique!

PRESS RELEASE NAIROBI, 27TH MARCH 2017 TRACE MZIKI, THE TV CHANNEL DEDICATED TO URBAN MUSIC FROM EASTERN AFRICA LAUNCHED IN FRENCH-SPEAKING AFRICA WITH CANAL + AFRIQUE! TRACE Mziki is now available in the Evasion bundle of Canal+ Afrique offer via satellite (channel 131), and will soon be launched in Easy TV DTT offer in the Democratic Republic of Congo. TRACE Mziki is the #1 channel for all Eastern Africa music lovers. With an eclectic choice of music genre from Afro Fusion, Genge Music to Bongo Flava as well as local Hip Hop and Dancehall, this channel curates the best afro-urban hits coming from Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Uganda and Rwanda. It showcases artists like Venessa Mdee, Ommy Dimpoz and Sauti Sol. Launched in September 2016 in both Swahili and English, TRACE Mziki quickly settled as the reference channel from Eastern African music in the main television paying offers in Eastern and central Africa: DSTV, Canal+, Zuku and Kwesé. TRACE Mziki’s motto, “ Twapenda Mizki Chem Chem ” means “ We love hot and steamy music ” in Swahili. This Eastern African language is spoken by more than 200 million people in the world. Olivier Laouchez, Cofounder, Chairman and and CEO of TRACE declares: « For the last 14 years, TRACE has continuously shown its passion and commitment for urban, African and Caribbean music. With TRACE Mziki, we are proud to display the Swahili language and talented artists who make East Africa dance. The arrival of TRACE Mziki on Canal+ in French-speaking Africa shows once again that music has no borders. » ABOUT TRACE Launched in 2003 by Olivier Laouchez, TRACE is a multimedia group and brand dedicated to afro-urban entertainment. -

Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Krystal A

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 1-1-2015 Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Krystal A. Smalls University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the African American Studies Commons, Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Smalls, Krystal A., "Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2022. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2022 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2022 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Black Semiosis: Young Liberian Transnationals Mediating Black Subjectivity and Black Heterogeneity Abstract From the colonization of the “Dark Continent,” to the global industry that turned black bodies into chattel, to the total absence of modern Africa from most American public school curricula, to superfluous representations of African primitivity in mainstream media, to the unflinching state-sanctioned murders of unarmed black people in the Americas, antiblackness and anti-black racism have been part and parcel to modernity, swathing centuries and continents, and seeping into the tiny spaces and moments that constitute social reality for most black-identified -

Nz Major Markets Commercial Radio

EMBARGOED UNTIL 1PM (NZDT) THURS NOV 21 2019 NZ MAJOR MARKETS COMMERCIAL RADIO - SURVEY 4 2019 Station Share (%) by Demographic, Mon-Sun 12mn-12mn Survey Comparisons: 3/2019 - 4/2019 This Survey Period: Metro - Sun Jun 16 to Sat Nov 2 2019 / Regional - Sun Jan 20* to Sat Jun 8 & Sun Jun 16 to Sat Nov 2 2019 *Northland Wave 1 field dates Feb 3 to Mar 30 (Waikato - Sun Aug 21 to Sat Oct 22 2016 & Sun Jan 29 to Sat Jun 17 & Sun Jul 2 to Sat Sep 9 2017) Last Survey Period: Metro - Sun Mar 31 to Sat Jun 8 & Sun Jun 16 to Sat Aug 24 2019 / Regional - Sun Sep 2 to Sat Nov 10 2018 & Sun Jan 20* to Sat Jun 8 & Sun Jun 16 to Sat Aug 24 2019 *Northland Wave 1 field dates Feb 3 to Mar 30 (Waikato - Sun Aug 21 to Sat Oct 22 2016 & Sun Jan 29 to Sat Jun 17 & Sun Jul 2 to Sat Sep 9 2017) All 10+ People 10-17 People 18-34 People 25-44 People 25-54 People 45-64 People 55-74 MGS with Kids This Last +/- Rank This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- Network Breeze 9.3 8.8 0.5 2 5.3 6.1 -0.8 6.6 5.9 0.7 8.3 7.2 1.1 9.0 8.1 0.9 11.3 11.4 -0.1 12.8 12.0 0.8 10.4 10.1 0.3 Network Coast 7.0 6.5 0.5 6 4.3 3.4 0.9 3.9 2.3 1.6 3.9 2.7 1.2 5.1 4.1 1.0 9.0 8.3 0.7 11.9 11.6 0.3 4.1 4.3 -0.2 Network The Edge 6.1 6.5 -0.4 8 13.4 16.8 -3.4 12.1 12.8 -0.7 9.1 8.7 0.4 7.3 7.1 0.2 3.3 3.5 -0.2 1.5 1.8 -0.3 8.6 8.0 0.6 Network Flava 1.5 1.5 0.0 15 3.5 3.1 0.4 3.6 3.5 0.1 2.4 2.3 0.1 1.8 1.6 0.2 0.4 0.5 -0.1 0.1 0.3 -0.2 2.1 2.5 -0.4 Network George FM 1.8 2.1 -0.3 14 2.4 1.4 1.0 3.5 3.7 -0.2 3.3 3.3 0.0 2.7 3.1 -0.4 -

Your Direct Line to New Zealand

YOUR DIRECT LINE TO NEW ZEALAND EXCLUSIVE CANDIDATE ELECTION RATES Take your campaign message to over 3.1 million Kiwis* with a cost-effective NZME media campaign. NZME publishes the country’s most influential media brands – commanding huge and highly engaged daily audiences. Harness a combination of digital, print and radio to broadcast your message countrywide – or target your own electorate locally using the capabilities of the NZME Local Network. Win over the New Zealand electorate with the help of NZME. See next page for exclusive advertising rates. EXCLUSIVE CANDIDATE RATES 15th July – 7th October (as per ASA advice 2016) RADIO • On average Kiwis listen to just under 2 hours a day.* • Radio is the perfect platform to drive recognition and trust. 45% off1 PRINT • 1.9 million Kiwis read NZME print brands** – including its 23 regional community titles. 2 • Newspapers help Kiwis form new opinions. 15% off DIGITAL • NZME reaches 2.4 million Kiwis around NZ through its digital brands – 69% of all people in the North Island & 62% of all people in the South Island.** • Kiwis seek accurate and credible information from digital news sites. 15% off3 Contact: [email protected] *Source: NZ on Air Annual Report 13/14 as conducted by Colmar Brunton. **Source: Nielsen CMI Fused Q1 15 - Q4 15 March 16 TV/Online AP15+ (1) Discount off current ratecard. No VID, no bonus, no Time Saver Traffic, News Sponsorship Credits or Headliners. (2) Discount off current ratecard. No VID, no bonus. (3) Discount off current ratecard. No Branded Content, Sponsorships, Mobile Daily Blast, Google Adwords and other offnet activity. -

Usawiri Wa Masuala Ya Kijinsia Katika Lugha Ya Mashairi: Mifano Kutoka Mashairi Ya Bongo Fleva Tanzania

USAWIRI WA MASUALA YA KIJINSIA KATIKA LUGHA YA MASHAIRI: MIFANO KUTOKA MASHAIRI YA BONGO FLEVA TANZANIA AMBARAK IBRAHIM SALEH KHALIFA TASINIFU YA M.A KISWAHILI CHUO KIKUU HURIA CHA TANZANIA 2013 USAWIRI WA MASUALA YA KIJINSIA KATIKA LUGHA YA MASHAIRI: MIFANO KUTOKA MASHAIRI YA BONGO FLEVA TANZANIA AMBARAK IBRAHIM SALEH KHALIFA TASINIFU ILIYOWASILISHWA KWA MINAJILI YA KUKAMILISHA MASHARTI YA DIGRII YA M.A KISWAHILI YA CHUO KIKUU HURIA CHA TANZANIA 2013 ii UTHIBITISHO Aliyetia saini hapa chini anathibitisha kuwa amesoma Tasinifu hii iitwayo: Usawiri wa masuala ya Kijinsia katika Lugha ya mashairi: Mifano kutoka Mashairi ya Bongo Fleva, na kupendekeza ikubaliwe na Chuo Kikuu Huria cha Tanzania kwa ajili ya kukamilisha masharti ya Digirii ya M.A. Kiswahili ya Chuo Kikuu Huria cha Tanzania. ----------------------------------------- Sheikh, Professa, Dkt. T.S.Y.SENGO (MSIMAMIZI) Tarehe ----------------------------- iii IKIRARI NA HAKIMILIKI Mimi, Ambarak Ibrahim Salehe Khalifa, nathibitisha kuwaTasinifu hii ni kazi yangu halisi na haijawahi kuwasilishwa katika Chuo Kikuu kingine kwa ajili ya Digirii yoyote. Sahihi........................................................ Haki ya kunakili tasinifu hii inalindwa na mkataba wa Berne, Sheria ya haki ya kunakili ya mwaka 1999 na mikataba mingine ya sheria za kitaifa na kimataifa zinazolinda mali ya kitaaluma. Haki zote zimehifadhiwa. Hairuhusiwi kuiga au kunakili kwa njia yoyote ile, iwe ama yote au sehemu ya Tasinifu hii, isipokuwa shughuli halali, kwa ajili ya utafiti, kujisomea au kufanya marejeo ya kitaaluma bila kibali cha maandishi cha Mkuu wa Kurugenzi ya Taaluma za Uzamili kwa niaba ya Chuo Kikuu Huria cha Tanzania. iv SHUKURANI Kwa hakika si kazi rahisi kuwataja na kuwashukuru kwa majina wote waliochangia kukamilika kwa utafiti huu.