Mothering and Attention Deficit Disorder: the Impact of Professional Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Tracking List Edition January 2021

AN ISENTIA COMPANY Australia Media Tracking List Edition January 2021 The coverage listed in this document is correct at the time of printing. Slice Media reserves the right to change coverage monitored at any time without notification. National National AFR Weekend Australian Financial Review The Australian The Saturday Paper Weekend Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 2/89 2021 Capital City Daily ACT Canberra Times Sunday Canberra Times NSW Daily Telegraph Sun-Herald(Sydney) Sunday Telegraph (Sydney) Sydney Morning Herald NT Northern Territory News Sunday Territorian (Darwin) QLD Courier Mail Sunday Mail (Brisbane) SA Advertiser (Adelaide) Sunday Mail (Adel) 1st ed. TAS Mercury (Hobart) Sunday Tasmanian VIC Age Herald Sun (Melbourne) Sunday Age Sunday Herald Sun (Melbourne) The Saturday Age WA Sunday Times (Perth) The Weekend West West Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 3/89 2021 Suburban National Messenger ACT Canberra City News Northside Chronicle (Canberra) NSW Auburn Review Pictorial Bankstown - Canterbury Torch Blacktown Advocate Camden Advertiser Campbelltown-Macarthur Advertiser Canterbury-Bankstown Express CENTRAL Central Coast Express - Gosford City Hub District Reporter Camden Eastern Suburbs Spectator Emu & Leonay Gazette Fairfield Advance Fairfield City Champion Galston & District Community News Glenmore Gazette Hills District Independent Hills Shire Times Hills to Hawkesbury Hornsby Advocate Inner West Courier Inner West Independent Inner West Times Jordan Springs Gazette Liverpool -

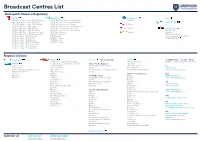

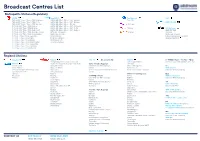

Broadcast Centres List

Broadcast Centres List Metropolita Stations/Regulatory 7 BCM Nine (NPC) Ten Network ABC 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide Ten (10) 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane FREE TV CAD 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 10 Peach 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sydney 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth 10 Bold SBS National 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD/ SBS 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast GTV Nine Melbourne 10 Shake Viceland 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns QTQ Nine Brisbane WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay STW Nine Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton TCN Nine Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Regional Stations Imparaja TV Prime 7 SCA TV Broadcast in HD WIN TV 7 / 7TWO / 7mate / 9 / 9Go! / 9Gem 7TWO Regional (REG QLD via BCM) TEN Digital Mildura Griffith / Loxton / Mt.Gambier (SA / VIC) NBN TV 7mate HD Regional (REG QLD via BCM) SC10 / 11 / One Regional: Ten West Central Coast AMB (Nth NSW) Central/Mt Isa/ Alice Springs WDT - WA regional VIC Coffs Harbour AMC (5th NSW) Darwin Nine/Gem/Go! WIN Ballarat GEM HD Northern NSW Gold Coast AMD (VIC) GTS-4 -

Your Prime Time Tv Guide ABC (Ch2) SEVEN (Ch6) NINE (Ch5) WIN (Ch8) SBS (Ch3) 6Pm the Drum

tv guide PAGE 2 FOR DIGITAL CHOICE> your prime time tv guide ABC (CH2) SEVEN (CH6) NINE (CH5) WIN (CH8) SBS (CH3) 6pm The Drum. 6pm Seven Local News. 6pm Nine News. 6pm News. 6pm Mastermind Australia. 7.00 ABC News. 6.30 Seven News. 7.00 A Current Affair. 6.30 The Project. 6.30 News. Y 7.30 Gardening Australia. 7.00 Better Homes And Gardens. 7.30 Rugby League. NRL. Round 17. 7.30 The Living Room. 7.30 Secrets Of The Railway. A 8.30 MotherFatherSon. (M) The 8.30 MOVIE The Butler. (2013) (M) Rabbitohs v Storm. 8.30 Have You Been Paying 8.25 Greek Island Odyssey With D I prime minister’s son is murdered. Forest Whitaker, Oprah Winfrey. The 9.45 Friday Night Knock Off. Attention? (M) Bettany Hughes. (PG) Bettany 9.30 Miniseries: The Accident. (M) story of a White House butler. 10.35 MOVIE Dead Man Down. 9.30 Just For Laughs heads to Crete. FR Part 1 of 4. 11.10 To Be Advised. (2013) (MA15+) Colin Farrell. A Uncut. (MA15+) 9.30 Cycling. Tour de France. Stage 7. 10.20 ABC Late News. killer is seduced by a woman 10.00 Just For Laughs. (MA15+) 10.45 The Virus. seeking revenge. 10.30 The Project. 7pm ABC News. 6pm Seven News. 6pm Nine News Saturday. 6pm To Be Advised. 6.30pm News. Y 7.30 Father Brown. (PG) Hercule 7.00 Border Patrol. (PG) 7.00 A Current Affair. 7.00 Bondi Rescue. (PG) 7.30 Walking Britain’s Lost A Flambeau visits Kembleford. -

Read the Report "Content, Consolidation and Clout

Content, Consolidation And Clout How will regional Australia be affected by media ownership changes? A report by the Communications Law Centre 2006 Funded by a Faculty Grant from the University of New South Wales, 2005 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all those in Wollongong, Launceston, Townsville and Toowoomba who participated in the focus groups for this study, and the academics, commentators and journalists who gave us their time and insights. Special thanks go to: Elizabeth Beal, Philip Bell, Ginger Briggs, Lesley Hitchens, Jock Given, Julie Hillocks, Geoff Lealand, Julie Miller, Nick Moustakas and Julian Thomas. Analysis of media companies and a draft of some sections of Chapter Four were provided by Danny Yap as part of a placement for the University of New South Wales Law School social justice internship program. The Faculty Research Grants Committees of the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at UNSW provided funding for the initial part of this project including the field work in regional centres. The project was completed by the authors following the closure of the Communications Law Centre at UNSW in June 2005. The CLC continues its policy, research and advocacy work through its centre at Victoria University. About the authors Tim Dwyer is Lecturer in Media Policy and Research at the School of Communication Arts, University of Western Sydney. Derek Wilding was Director of the Communications Law Centre from 2000 to 2005. Before that he worked for the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance and at Queensland University of Technology. He is currently a Principal Policy Officer with the Office of Film and Literature Classification. -

Hansard 9 May 2002

9 May 2002 Legislative Assembly 1357 THURSDAY, 9 MAY 2002 Mr SPEAKER (Hon. R. K. Hollis, Redcliffe) read prayers and took the chair at 9.30 a.m. PETITIONS Coominya Fishing Club; Wivenhoe Dam Mr Livingstone from 2,982 petitioners, requesting the House to (a) require the Coominya Fishing Club to remove the locked gate at McLean's Point and (b) not allow or consider further leasing of land to private fishing clubs along the Wivenhoe Dam shoreline. Recreational Fishing, Hervey Bay Mr McNamara from 3,140 petitioners, requesting the House to amend the Fisheries Regulations to declare the southern part of Hervey Bay and the Great Sandy Strait a recreational only fishing area. Tewantin Fire and Rescue Station Ms Molloy from 9,109 petitioners, requesting the House to take all necessary steps to ensure the continuation of the Tewantin Fire and Rescue Station and related services and that the facility be extended to protect the continually expanding population, health, aged and other care facilities as well as the increasingly significant environmental areas. MINISTERIAL STATEMENT Queensland BioCapital Fund Hon. P. D. BEATTIE (Brisbane Central—ALP) (Premier and Minister for Trade) (9.32 a.m.), by leave: Today I am delighted to announce a major breakthrough in investment in the Smart State. Today the Treasurer and I will announce, along with the QIC, a government owned corporation, that $100 million has been committed to a Queensland based venture capital fund to invest in biotechnology. I detail today that the fund will be managed by the Queensland government's fund management arm, the Queensland Investment Corporation. -

Adstream Powerpoint Presentation

Broadcast Centres List Metropolitan Stations/Regulatory Nine (NPC) 7 BCM 7 BCM cont’d Nine (NPC) cont’d Ten Network 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide 7HD & SD / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton QTQ Nine Brisbane Ten HD (all metro) 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane 7HD & SD / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba STW Nine Perth Ten SD (all metro) 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 7HD & SD / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville TCN Nine Sydney One (all metro) 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Channel 11 (all metro) 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth SBS National 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD / 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD / SBS Free TV CAD 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast ABC GTV Nine Melbourne Viceland 7 / 7mate HD / 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay Regional Stations Prime 7 cont’d SCA TV Cont’d WIN TV cont’d VIC Mildura Bendigo WIN / 11 / One Regional: WIN Ballarat Send via WIN Wollongong Imparja TV Newcastle Bundaberg Albury Orange/Dubbo Ballarat Canberra NBN TV Port Macquarie/Taree Bendigo QLD Shepparton Cairns Central Coast Canberra WIN Rockhampton South Coast Dubbo Cairns Send via WIN Wollongong Coffs Harbour -

The Application of in Situ Digital Networks to News Reporting and Delivery

The Application of in situ Digital Networks to News Reporting and Delivery Author Cokley, John D Published 2005 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts, Media and Culture DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2229 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/365482 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au 1 The application of in situ digital networks to news reporting and delivery Keywords: information theory; participatory communication; community capacity building; diffusion of innovations; media dependency; hegemony. Thesis submitted to complete the degree Doctor of Philosophy at Griffith University, Nathan, Australia Volume 1: Introductions, text and references Volume 2: Appendices By John Cokley, B. Business (Communication) GUID: 1629909 School of Arts, Media and Culture Faculty of Arts Griffith University Brisbane 12 December 2004 Supervisor: Associate Professor Michael Meadows, PhD Co-supervisors: Dr Steve Drew; Professor Paul Turnbull, PhD 2 3 Declaration I, John Damien Cokley (the undersigned candidate), declare that this work has not previously been submitted for a degree or diploma at any university. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the thesis itself. I also confirm that ethical issues have been considered and that I have been advised there has been no requirement to seek approval from the university’s ethics committee. Signed John D. Cokley 12 December 2004 4 5 Acknowledgements This work, like so much of journalism and research, has been an effort that – while focussed by one person, the author – has drawn on the personal efforts of many others. -

S Sh Ow Wc Car Rds S

Morgan Gallup Poll SSHOWWCCARDS Yoour Opinion Counts Your answers to all questions will be treated in strict confidence and only used for statistical purposess. Queensland Rounds: 2440 / 2441 / 2442 / 2443 PAGE 1 QLD ROTATION 1 1/4 x:\systems\database\cards\docs\2500\2070.doc Front page - QLD Q 4 ES 2440 / 2441 / 2442 / 2443 PAGE 1 Alfa Romeo Holden Kia Mini Tesla 8501 Giulia 1531 Acadia 7930 Carnival 9545 Cabrio/Convertible 0603 Model 3 8499 Giulietta 1230 Astra 7344 Cerato 9544 Clubman 0601 Model S 8502 Stelvio 1110 Barina 7540 Optima 9540 Cooper/Hatch 0602 Model X 1832 Captiva 7343 Picanto 9541 Countryman Audi Toyota 1886 Colorado 7215 Rio Mitsubishi 8636 A1/S1 4120 86 1512 Commodore Tourer 7347 Rondo 3110 ASX 8696 A3/S3 4121 C-HR 1506 Commodore 7216 Sorento 3201 Eclipse Cross 4320 Camry/Camry Hybrid 8693 A4/S4 3210 Lancer 1602 Equinox 7348 Soul 4200 Corolla 8738 A5/S5 3230 Mirage 1570 HSV (Holden Special 7213 Sportage 4214 Fortuner 8694 A6/S6 Vehicle) 3713 Outlander PHEV 7142 Stinger 4830 Hiace 8727 A7/S7 1112 Spark 3711 Outlander Land Rover 4820 Hilux 8695 A8/S8 1819 Trailblazer 3235 Pajero Sport 9840 Defender 4861 Kluger 8728 Q2 1879 Trax 3860 Pajero 8726 Q3 9831 Discovery Sport 3820 Triton 4950 Landcruiser Honda 8737 Q5 9830 Discovery Nissan 4880 Prado 9721 Range Rover Evoque 4116 Prius C 8735 Q7 7300 Accord 5386 350Z/370Z 9615 Range Rover Sport 4117 Prius V 8699 TT 7303 City 5401 Juke 9611 Range Rover Velar 4115 Prius 7200 Civic 5387 Leaf BMW 9610 Range Rover 4760 RAV4 7840 CR-V 5850 Navara PAGE 2 PAGE 2 8446 1-Series 4730 Tarago -

Broadcast Centres List

Broadcast Centres List Metropolita Stations/Regulatory 7 BCM Nine (NPC) Ten Network ABC 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide Ten (10) 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane FREE TV CAD 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 10 Peach 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sydney 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth 10 Bold SBS National 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD/ SBS 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast GTV Nine Melbourne 10 Shake Viceland 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns QTQ Nine Brisbane WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay STW Nine Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton TCN Nine Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Regional Stations Imparaja TV Prime 7 SCA TV Broadcast in HD WIN TV 7 / 7TWO / 7mate / 9 / 9Go! / 9Gem 7TWO Regional (REG QLD via BCM) TEN Digital Mildura Griffith / Loxton / Mt.Gambier (SA / VIC) NBN TV 7mate HD Regional (REG QLD via BCM) SC10 / 11 / One Regional: Ten West Central Coast AMB (Nth NSW) Central/Mt Isa/ Alice Springs WDT - WA regional VIC Coffs Harbour AMC (5th NSW) Darwin Nine/Gem/Go! WIN Ballarat GEM HD Northern NSW Gold Coast AMD (VIC) GTS-4 -

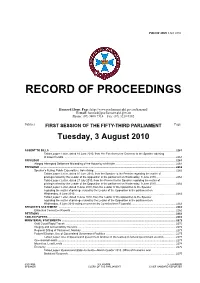

Record of Proceedings

PROOF ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/hansard/ E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (07) 3406 7314 Fax: (07) 3210 0182 Subject FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT Page Tuesday, 3 August 2010 ASSENT TO BILLS ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2261 Tabled paper: Letter, dated 18 June 2010, from Her Excellency the Governor to the Speaker advising of assent to bills. .................................................................................................................................................... 2261 PRIVILEGE ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 2261 Alleged Attempted Deliberate Misleading of the House by a Minister ................................................................................ 2261 PRIVILEGE ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 2262 Speaker’s Ruling, Public Expenditure, Advertising ............................................................................................................ 2262 Tabled paper: Letter, dated 10 June 2010, from the Speaker to the Premier regarding the matter of privilege raised by the -

10 March 2021

ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/work-of-assembly/hansard Email: [email protected] Phone (07) 3553 6344 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT Wednesday, 10 March 2021 Subject Page SPEAKER’S RULING ........................................................................................................................................................... 403 Tabled Paper, Withdrawal and Replacement ................................................................................................... 403 SPEAKER’S STATEMENTS ................................................................................................................................................. 403 Tabled Papers, Procedures .............................................................................................................................. 403 School Group Tours .......................................................................................................................................... 403 TABLED PAPER ................................................................................................................................................................... 403 MINISTERIAL STATEMENTS ............................................................................................................................................... 404 Coronavirus, Update; Coronavirus, Vaccine .................................................................................................. -

Television Coverage National

TELEVISION COVERAGE NATIONAL NORTHERN SOUTHERN TARGET / MARKET QLD VICTORIA TASMANIA TOTALS NSW NSW TOTAL 787,700 899,000 612,700 517,800 223,500 3,040,700 HOUSEHOLDS TOTAL 1,853,900 2,183,900 1,499,100 1,192,200 524,000 7,253,100 INDIVIDUALS BY NETWORK NINE NETWORK NINE NETWORK (NBN) SGT CENTRAL DIGITAL TELEVISION IMPARJA DARWIN DIGITAL TELEVISION NINE TELEVISION DARWIN SEVEN NETWORK *Note this map displays SCA owned television networks, joint ventures, and television products sold on behalf of non SCA networks. TELEVISION COVERAGE NATIONAL NORTHERN SOUTHERN TARGET / MARKET QLD VICTORIA TASMANIA TOTALS NSW NSW TOTAL 787,700 899,000 612,700 517,800 223,500 3,040,700 HOUSEHOLDS TOTAL 1,853,900 2,183,900 1,499,100 1,192,200 524,000 7,253,100 INDIVIDUALS BY REGION QUEENSLAND NINE NETWORK NORTHERN NEW SOUTH WALES NINE NETWORK (NBN) SOUTHERN NEW SOUTH WALES NINE NETWORK VICTORIA NINE NETWORK SOUTH AUSTRALIA SGT TASMANIA SEVEN NETWORK DARWIN SEVEN NETWORK DARWIN DIGITAL TELEVISION NINE TELEVISION DARWIN *Note this map displays SCA owned television networks, joint ventures, and television products sold on behalf of non SCA networks. CENTRAL SEVEN NETWORK CENTRAL DIGITAL TELEVISION IMPARJA TELEVISION COVERAGE QUEENSLAND POTENTIAL AUDIENCES BY COVERAGE AREA Mossman MARKET NETWORK AUDIENCE Port Douglas CAIRNS NINE (9, 9HD, GEM, GO!, Life) 259,600 CAIRNS Green Island Mareeba TOWNSVILLE NINE (9, 9HD, GEM, GO!, Life) 239,100 Atherton Innisfail MACKAY NINE (9, 9HD, GEM, GO!, Life) 192,500 Mission Beach Tully Cardwell Dunk Island / Bedarra Island ROCKHAMPTON