The Application of in Situ Digital Networks to News Reporting and Delivery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sasha Mackay Thesis

STORYTELLING AND NEW MEDIA TECHNOLOGIES: INVESTIGATING THE POTENTIAL OF THE ABC’S HEYWIRE FOR REGIONAL YOUTH Sasha Mackay Bachelor of Fine Arts (Hons), Creative Writing Production Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2015 Keywords Australian Broadcasting Corporation Heywire new media narrative identity public service media regional Australia storytelling voice youth Storytelling and new media technologies: investigating the potential of the ABC’s Heywire for regional youth i Abstract This thesis takes a case study approach to examine the complexity of audience participation within the Australian public service media institution, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). New media technologies have both enabled and necessitated an increased focus on user created content and audience participation within the context of public service media (PSM) worldwide and such practices are now embedded within the remit of these institutions. Projects that engage audiences as content creators and as participants in the creation of their own stories are now prevalent within PSM; however, these projects represent spaces of struggle: a variety of institutional and personal agendas intersect in ways that can be fruitful though at other times produce profound challenges. This thesis contributes to the wider conversation on audience participation in the PSM context by examining the tensions that emerge at this intersection of agendas, and the challenges and potentials these produce for the institution as well as the individuals whose participation it invites. The case study for this research – Heywire – represents one of the first instances of content-related participation within the ABC. -

Margaret Klaassen Thesis (PDF 1MB)

AN EXAMINATION OF HOW THE MILITARY, THE CONSERVATIVE PRESS AND MINISTERIALIST POLITICIANS GENERATED SUPPORT WITHIN QUEENSLAND FOR THE WAR IN SOUTH AFRICA IN 1899 AND 1900 Margaret Jean Klaassen ASDA, ATCL, LTCL, FTCL, BA 1988 Triple Majors: Education, English & History, University of Auckland. The University Prize in Education of Adults awarded by the Council of the University of Auckland, 1985. Submitted in full requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Division of Research & Commercialisation Queensland University of Technology 2014 Keywords Anglo-Boer War, Boer, Brisbane Courier, Dawson, Dickson, Kitchener, Kruger, Orange Free State, Philp, Queensland, Queenslander, Transvaal, War. ii Abstract This thesis examines the myth that Queensland was the first colonial government to offer troops to support England in the fight against the Boers in the Transvaal and Orange Free State in 1899. The offer was unconstitutional because on 10 July 1899, the Premier made it in response to a request from the Commandant and senior officers of the Queensland Defence Force that ‘in the event of war breaking out in South Africa the Colony of Queensland could send a contingent of troops and a machine gun’. War was not declared until 10 October 1899. Under Westminster government conventions, the Commandant’s request for military intervention in an overseas war should have been discussed by the elected legislators in the House. However, Parliament had gone into recess on 24 June following the Federation debate. During the critical 10-week period, the politicians were in their electorates preparing for the Federation Referendum on 2 September 1899, after which Parliament would resume. -

Australian Journalism Research Index 1992-99 Anna Day

Australian journalismAustralian research Studies index in Journalism 1992-98 8: 1999, pp.239-332 239 Australian journalism research index 1992-99 Anna Day This is an index of Australian journalism and news media- related articles and books from 1992 onwards. The index is in two main parts: a listing by author, and a listing by subject matter in which an article may appear a number of times. Multi- author articles are listed by each author. To advise of errors or omissions, or to have new material included in the next edition, please contact Anna Day at [email protected] Source journals (AsianJC) Asian Journal of Communication. (AJC) Australian Journal of Communication. Published by the School of Communication and Organisations Studies and the Communication Centre, Queensland University of Technology; edited by Roslyn Petelin. Address: c/- Roslyn Petelin, School of Communication and Organisational Studies, Faculty of Business, Queensland University of Technology, GPO Box 2434, Brisbane, Qld 4001. (AJR) Australian Journalism Review. Published by the Journalism Education Association; edited by Lawrence Apps of the Curtin University School of Communication and Cultural Studies, PO Box U1987, Perth WA, 6001. Phone: (09) 351 3247. Fax: (09) 351 7726. (ASJ) Australian Studies in Journalism. Published by the Department of Journalism at the University of Queensland; edited by Professor John Henningham. Founded 1992. Address: Department of Journalism, University of Queensland, 4072. Phone: (07) 3365 2060. Fax: (07) 3365 1377. (BJR) British Journalism Review. Published by British Journalism Review Publishing Ltd, a non-profit making company. (CJC) Canadian Journal of Communication. Published by Wildrid Laurier University Press for the non-profit Canadian Journal of Communication Corporation, and is a collaborative venture between the Centre for Policy Research on Science and Technology and the Canadian Centre for Studies in Publishing; edited by Rowland Lorimer of the School of Communication, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, B.C., Canada. -

Beyond the 5Ws + H: What Social Science Can Bring to J-Education

Asia Pacific Media ducatE or Issue 17 Article 2 12-2006 Beyond the 5Ws + H: What social science can bring to J-education K.C. Boey Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/apme Recommended Citation Boey, K.C., Beyond the 5Ws + H: What social science can bring to J-education, Asia Pacific Media Educator, 17, 2006, 1-4. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/apme/vol1/iss17/2 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Beyond the 5Ws + H: What Social Science Can Bring to J-Education K.C. Boey Journalist, Melbourne THE pen is mightier than the sword. This axiom of journalism is at no time more apposite than in this terror-ridden post-9/11 world. Increasingly, nation-states and activist bloggers are realising that the power of the media and those who control it set the agenda for world politics and governance. Yet journalism educators reflexively trust this maxim among their charges to received wisdom. Or pedantically go on presuming this aphorism to be ingrained in them by the time they finish high school media studies. In this, educators sell short students – and fall short of their larger responsibility to our broken world – neglecting the development of future journalists in a critical area of their calling. The might of the pen – or more precisely the keyboard in today’s electronically wired world – rests on two planks. The first is the substance of people dialogue and communication, mediated through the media. -

Media Tracking List Edition January 2021

AN ISENTIA COMPANY Australia Media Tracking List Edition January 2021 The coverage listed in this document is correct at the time of printing. Slice Media reserves the right to change coverage monitored at any time without notification. National National AFR Weekend Australian Financial Review The Australian The Saturday Paper Weekend Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 2/89 2021 Capital City Daily ACT Canberra Times Sunday Canberra Times NSW Daily Telegraph Sun-Herald(Sydney) Sunday Telegraph (Sydney) Sydney Morning Herald NT Northern Territory News Sunday Territorian (Darwin) QLD Courier Mail Sunday Mail (Brisbane) SA Advertiser (Adelaide) Sunday Mail (Adel) 1st ed. TAS Mercury (Hobart) Sunday Tasmanian VIC Age Herald Sun (Melbourne) Sunday Age Sunday Herald Sun (Melbourne) The Saturday Age WA Sunday Times (Perth) The Weekend West West Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 3/89 2021 Suburban National Messenger ACT Canberra City News Northside Chronicle (Canberra) NSW Auburn Review Pictorial Bankstown - Canterbury Torch Blacktown Advocate Camden Advertiser Campbelltown-Macarthur Advertiser Canterbury-Bankstown Express CENTRAL Central Coast Express - Gosford City Hub District Reporter Camden Eastern Suburbs Spectator Emu & Leonay Gazette Fairfield Advance Fairfield City Champion Galston & District Community News Glenmore Gazette Hills District Independent Hills Shire Times Hills to Hawkesbury Hornsby Advocate Inner West Courier Inner West Independent Inner West Times Jordan Springs Gazette Liverpool -

Arrival of South Sea Islanders in Queensland

ARRIVAL OF SOUTH SEA ISLANDERS IN QUEENSLAND The Courier, Tuesday 18 August 1863, page 5 The schooner Don Juan, the arrival of which was noted in our issue of yesterday, is from the group of islands in the Pacific named the New Hebrides. She brings a number of the natives of those islands to be employed as laborers by Captain Towns on his cotton plantation, on the Logan River, at the remuneration of 10s. per month, with rations, as is currently reported. We understand that there are sixty‐seven natives on board, and that one man died on the passage. The Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 22 August 1863, page 6 Brisbane, Arrival. August 15. – Don Juan, from South Sea Islands. The schooner Don Juan, Captain Grueber, left Erromanga on the 4th instant, sighted Moreton light at 3 o’clock on Friday morning, rounded Moreton Island at 8 a.m., and anchored off the lightship at 9 p.m. During the passage she experienced a fine S.E. breeze and fine weather until the 12th instant, when the wind changed and blew a heavy gale from the N.E. The Don Juan has on board in all seventy‐three South Sea Islanders for Captain Towns’ cotton plantation. One of the islanders died on Saturday last from exhaustion caused by sea sickness. He was buried on Mud Island. The agreement made with these men is, that they shall receive ten shillings a month, and have their food, clothes, and shelter provided for them. – Queensland Guardian, August 18, The North Australian, 20 August 1863 The arrival of the Don Juan, schooner, at the port of Brisbane, with sixty‐seven natives of the New Hebrides, to, be employed on Captain Towns Cotton Plantation at the Logan River, would under any circumstances be an addition to the population of the colony worthy of more than ordinary notice. -

The Making of White Australia

The making of White Australia: Ruling class agendas, 1876-1888 Philip Gavin Griffiths A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University December 2006 I declare that the material contained in this thesis is entirely my own work, except where due and accurate acknowledgement of another source has been made. Philip Gavin Griffiths Page v Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xiii Abstract xv Chapter 1 Introduction 1 A review of the literature 4 A ruling class policy? 27 Methodology 35 Summary of thesis argument 41 Organisation of the thesis 47 A note on words and comparisons 50 Chapter 2 Class analysis and colonial Australia 53 Marxism and class analysis 54 An Australian ruling class? 61 Challenges to Marxism 76 A Marxist theory of racism 87 Chapter 3 Chinese people as a strategic threat 97 Gold as a lever for colonisation 105 The Queensland anti-Chinese laws of 1876-77 110 The ‘dangers’ of a relatively unsettled colonial settler state 126 The Queensland ruling class galvanised behind restrictive legislation 131 Conclusion 135 Page vi Chapter 4 The spectre of slavery, or, who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 137 The political economy of anti-slavery 142 Indentured labour: The new slavery? 149 The controversy over Pacific Islander ‘slavery’ 152 A racially-divided working class: The real spectre of slavery 166 Chinese people as carriers of slavery 171 The ruling class dilemma: Who will do ‘our’ work in the tropics? 176 A divided continent? Parkes proposes to unite the south 183 Conclusion -

Melbourne Radio

EMBARGOED UNTIL 9:30AM (AEST) MELBOURNE RADIO - SURVEY 4 2021 Share Movement (%) by Demographic, Mon-Sun 5.30am-12midnight People 10+ People 10-17 People 18-24 People 25-39 People 40-54 People 55-64 People 65+ Station This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- SEN 1116 2.8 2.9 -0.1 1.6 0.9 0.7 0.5 0.1 0.4 3.1 1.4 1.7 3.2 2.6 0.6 3.3 6.0 -2.7 2.8 3.8 -1.0 3AW 15.5 15.6 -0.1 5.9 2.0 3.9 0.4 1.5 -1.1 3.6 3.2 0.4 13.1 11.2 1.9 17.6 22.4 -4.8 32.5 32.8 -0.3 RSN 927 0.3 0.4 -0.1 * * * * 0.1 * * * * 0.4 0.1 0.3 0.5 0.5 0.0 0.4 1.1 -0.7 Magic 1278 1.3 1.0 0.3 * 0.1 * 0.7 0.2 0.5 1.6 0.6 1.0 1.4 0.7 0.7 1.4 1.0 0.4 1.5 1.9 -0.4 3MP 1377 1.0 0.9 0.1 0.1 * * * 0.2 * 0.1 0.1 0.0 0.8 1.3 -0.5 2.5 0.7 1.8 1.7 1.8 -0.1 101.9 FOX FM 7.0 7.8 -0.8 14.8 16.4 -1.6 11.3 10.3 1.0 13.4 14.3 -0.9 7.1 10.4 -3.3 3.8 3.6 0.2 0.6 0.1 0.5 GOLD104.3 10.4 11.1 -0.7 5.8 8.6 -2.8 11.3 13.1 -1.8 10.7 9.2 1.5 15.0 14.9 0.1 15.7 15.1 0.6 3.8 6.5 -2.7 KIIS 101.1 FM 5.5 6.4 -0.9 15.4 18.1 -2.7 10.7 14.4 -3.7 9.8 10.4 -0.6 4.9 5.9 -1.0 2.5 3.5 -1.0 0.5 0.2 0.3 105.1 TRIPLE M 4.7 5.2 -0.5 2.8 2.0 0.8 8.0 6.6 1.4 7.0 5.8 1.2 6.2 8.0 -1.8 4.7 8.2 -3.5 0.9 0.8 0.1 NOVA 100 6.7 7.8 -1.1 21.2 22.4 -1.2 11.4 14.5 -3.1 8.4 12.6 -4.2 7.6 8.9 -1.3 4.8 3.1 1.7 0.4 0.3 0.1 smoothfm 91.5 7.8 7.6 0.2 6.9 8.7 -1.8 5.9 3.3 2.6 6.5 5.5 1.0 7.8 7.7 0.1 9.4 8.0 1.4 8.9 10.1 -1.2 ABC MEL 11.1 8.8 2.3 2.3 1.0 1.3 5.5 2.8 2.7 4.3 4.5 -0.2 6.3 4.3 2.0 13.8 6.4 7.4 23.2 21.6 1.6 3RN 2.7 2.1 0.6 0.6 0.4 0.2 * * * 0.7 0.2 0.5 2.2 1.2 1.0 2.6 2.7 -

Women's Struggle for Top Jobs in the News Media

Women’s Struggle for Top Jobs in the News Media Louise North School of Applied Media and Social Sciences Monash University, Northways Rd, Churchill, VIC 3842 [email protected] Abstract: This chapter provides an overview of the rise of women and women leaders in the Australian news media and outlines aspects of newsroom culture that continue to hamper women’s career progression. The chapter draws on a recent global survey and literature on the status of women in the news media. The most recent and wide ranging global data shows that while women’s position in the news media workforce (including reporting roles) has changed little in fifteen years, women have made small inroads into key editorial leadership positions. Nevertheless, the relative absence of women in these senior roles remains glaring, particularly in the print media, and points to a hegemonically masculine newsroom culture that works to undermine women’s progress in the industry. Keywords: gender and journalism, female journalists, print media, workforce Women have long been thwarted from key editorial leadership roles in news organisations around the world, and this continues today. Indeed, feminist scholars and some journalists suggest that the most common obstacle to career progress (and therefore attaining leadership positions) reported by women journalists is the problem of male attitudes.1 Even in Nordic countries where gender empowerment is rated high, patriarchal conservatism is noted as a central impediment to women’s career advancement in journalism.2 In the news media those in editorial leadership positions decide on editorial direction and content, and staffing – among other things – and therefore determine the newsroom makeup and what the consumer understands as news. -

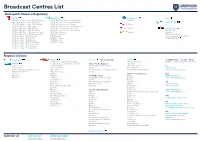

Broadcast Centres List

Broadcast Centres List Metropolita Stations/Regulatory 7 BCM Nine (NPC) Ten Network ABC 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide Ten (10) 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane FREE TV CAD 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 10 Peach 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sydney 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth 10 Bold SBS National 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD/ SBS 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast GTV Nine Melbourne 10 Shake Viceland 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns QTQ Nine Brisbane WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay STW Nine Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton TCN Nine Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Regional Stations Imparaja TV Prime 7 SCA TV Broadcast in HD WIN TV 7 / 7TWO / 7mate / 9 / 9Go! / 9Gem 7TWO Regional (REG QLD via BCM) TEN Digital Mildura Griffith / Loxton / Mt.Gambier (SA / VIC) NBN TV 7mate HD Regional (REG QLD via BCM) SC10 / 11 / One Regional: Ten West Central Coast AMB (Nth NSW) Central/Mt Isa/ Alice Springs WDT - WA regional VIC Coffs Harbour AMC (5th NSW) Darwin Nine/Gem/Go! WIN Ballarat GEM HD Northern NSW Gold Coast AMD (VIC) GTS-4 -

Sydney Radio

EMBARGOED UNTIL 9:30AM (AEST) SYDNEY RADIO - SURVEY 4 2021 Share Movement (%) by Demographic, Mon-Sun 5.30am-12midnight Station People 10+ People 10-17 People 18-24 People 25-39 People 40-54 People 55-64 People 65+ This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- This Last +/- SEN 1170 0.6 0.5 0.1 * * * 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.4 0.5 -0.1 0.4 0.2 0.2 0.1 * * 1.4 1.4 0.0 2GB 11.8 11.7 0.1 5.0 5.5 -0.5 2.0 1.7 0.3 4.2 3.4 0.8 3.7 4.4 -0.7 12.5 12.1 0.4 28.9 29.8 -0.9 2UE 954 3.0 2.4 0.6 0.1 1.3 -1.2 * 0.3 * 0.4 0.2 0.2 1.6 0.7 0.9 2.1 4.5 -2.4 8.3 5.4 2.9 SKY Sports Radio 0.7 0.7 0.0 0.8 0.3 0.5 0.5 0.2 0.3 1.1 1.0 0.1 0.3 0.8 -0.5 0.2 0.4 -0.2 1.1 0.9 0.2 104.1 2DAY FM 3.3 3.5 -0.2 4.7 5.3 -0.6 4.7 4.5 0.2 5.4 5.5 -0.1 3.6 4.5 -0.9 3.7 3.2 0.5 0.4 0.4 0.0 KIIS1065 10.6 9.6 1.0 12.1 12.9 -0.8 15.5 15.7 -0.2 23.1 18.7 4.4 12.4 11.1 1.3 3.9 4.8 -0.9 0.9 0.7 0.2 104.9 TRIPLE M 5.0 4.9 0.1 5.1 6.5 -1.4 12.7 11.0 1.7 4.9 5.4 -0.5 6.8 7.3 -0.5 6.0 4.1 1.9 0.8 0.8 0.0 NOVA96.9 6.7 6.5 0.2 23.4 19.7 3.7 14.3 11.7 2.6 11.2 11.5 -0.3 6.3 5.3 1.0 2.0 2.3 -0.3 0.2 0.5 -0.3 smoothfm 95.3 10.0 10.8 -0.8 9.4 6.6 2.8 9.9 8.1 1.8 9.4 9.6 -0.2 10.0 14.0 -4.0 15.3 14.4 0.9 7.6 8.7 -1.1 WSFM 8.3 8.2 0.1 7.3 10.0 -2.7 4.3 8.2 -3.9 5.1 5.9 -0.8 10.6 10.7 -0.1 15.1 12.5 2.6 6.0 4.7 1.3 ABC SYD 9.6 10.1 -0.5 3.7 4.6 -0.9 2.4 2.7 -0.3 2.7 3.2 -0.5 9.0 7.4 1.6 12.0 13.5 -1.5 17.7 20.2 -2.5 2RN 2.1 1.7 0.4 0.1 0.5 -0.4 2.0 0.7 1.3 0.4 0.2 0.2 1.5 1.3 0.2 2.7 2.9 -0.2 4.3 3.4 0.9 ABC NEWSRADIO 1.6 1.8 -0.2 0.7 1.3 -0.6 0.7 0.5 0.2 1.1 1.4 -0.3 -

Your Prime Time Tv Guide ABC (Ch2) SEVEN (Ch6) NINE (Ch5) WIN (Ch8) SBS (Ch3) 6Pm the Drum

tv guide PAGE 2 FOR DIGITAL CHOICE> your prime time tv guide ABC (CH2) SEVEN (CH6) NINE (CH5) WIN (CH8) SBS (CH3) 6pm The Drum. 6pm Seven Local News. 6pm Nine News. 6pm News. 6pm Mastermind Australia. 7.00 ABC News. 6.30 Seven News. 7.00 A Current Affair. 6.30 The Project. 6.30 News. Y 7.30 Gardening Australia. 7.00 Better Homes And Gardens. 7.30 Rugby League. NRL. Round 17. 7.30 The Living Room. 7.30 Secrets Of The Railway. A 8.30 MotherFatherSon. (M) The 8.30 MOVIE The Butler. (2013) (M) Rabbitohs v Storm. 8.30 Have You Been Paying 8.25 Greek Island Odyssey With D I prime minister’s son is murdered. Forest Whitaker, Oprah Winfrey. The 9.45 Friday Night Knock Off. Attention? (M) Bettany Hughes. (PG) Bettany 9.30 Miniseries: The Accident. (M) story of a White House butler. 10.35 MOVIE Dead Man Down. 9.30 Just For Laughs heads to Crete. FR Part 1 of 4. 11.10 To Be Advised. (2013) (MA15+) Colin Farrell. A Uncut. (MA15+) 9.30 Cycling. Tour de France. Stage 7. 10.20 ABC Late News. killer is seduced by a woman 10.00 Just For Laughs. (MA15+) 10.45 The Virus. seeking revenge. 10.30 The Project. 7pm ABC News. 6pm Seven News. 6pm Nine News Saturday. 6pm To Be Advised. 6.30pm News. Y 7.30 Father Brown. (PG) Hercule 7.00 Border Patrol. (PG) 7.00 A Current Affair. 7.00 Bondi Rescue. (PG) 7.30 Walking Britain’s Lost A Flambeau visits Kembleford.