Study Trip to East USA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

Recovery Plan for Liatris Helleri Heller’S Blazing Star

Recovery Plan for Liatris helleri Heller’s Blazing Star U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia RECOVERY PLAN for Liatris helleri (Heller’s Blazing Star) Original Approved: May 1, 1989 Original Prepared by: Nora Murdock and Robert D. Sutter FIRST REVISION Prepared by Nora Murdock Asheville Field Office U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Asheville, North Carolina for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Approved: Regional Director, U S Fish’and Wildlife Service Date:______ Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover andlor protect listed species. Plans published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) are sometimes prepared with the assistance ofrecovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and other affected and interested parties. Plans are reviewed by the public and submitted to additional peer review before they are adopted by the Service. Objectives of the plan will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not obligate other parties to undertake specific tasks and may not represent the views or the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in developing the plan, other than the Service. Recovery plans represent the official position ofthe Service only after they have been signed by the Director or Regional Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. By approving this recovery plan, the Regional Director certifies that the data used in its development represent the best scientific and commercial information available at the time it was written. -

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012 Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2012 Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 www.ncnhp.org NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM LIST OF THE RARE PLANTS OF NORTH CAROLINA 2012 Edition Edited by Laura E. Gadd, Botanist and John Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, Office of Conservation, Planning, and Community Affairs Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 1601 MSC, Raleigh, NC 27699-1601 www.ncnhp.org Table of Contents LIST FORMAT ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 NORTH CAROLINA RARE PLANT LIST ......................................................................................................................... 10 NORTH CAROLINA PLANT WATCH LIST ..................................................................................................................... 71 Watch Category -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- ERICACEAE

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- ERICACEAE ERICACEAE (Heath Family) A family of about 107 genera and 3400 species, primarily shrubs, small trees, and subshrubs, nearly cosmopolitan. The Ericaceae is very important in our area, with a great diversity of genera and species, many of them rather narrowly endemic. Our area is one of the north temperate centers of diversity for the Ericaceae. Along with Quercus and Pinus, various members of this family are dominant in much of our landscape. References: Kron et al. (2002); Wood (1961); Judd & Kron (1993); Kron & Chase (1993); Luteyn et al. (1996)=L; Dorr & Barrie (1993); Cullings & Hileman (1997). Main Key, for use with flowering or fruiting material 1 Plant an herb, subshrub, or sprawling shrub, not clonal by underground rhizomes (except Gaultheria procumbens and Epigaea repens), rarely more than 3 dm tall; plants mycotrophic or hemi-mycotrophic (except Epigaea, Gaultheria, and Arctostaphylos). 2 Plants without chlorophyll (fully mycotrophic); stems fleshy; leaves represented by bract-like scales, white or variously colored, but not green; pollen grains single; [subfamily Monotropoideae; section Monotropeae]. 3 Petals united; fruit nodding, a berry; flower and fruit several per stem . Monotropsis 3 Petals separate; fruit erect, a capsule; flower and fruit 1-several per stem. 4 Flowers few to many, racemose; stem pubescent, at least in the inflorescence; plant yellow, orange, or red when fresh, aging or drying dark brown ...............................................Hypopitys 4 Flower solitary; stem glabrous; plant white (rarely pink) when fresh, aging or drying black . Monotropa 2 Plants with chlorophyll (hemi-mycotrophic or autotrophic); stems woody; leaves present and well-developed, green; pollen grains in tetrads (single in Orthilia). -

Ground Vegetation Patterns of the Spruce-Fir Area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-1957 Ground Vegetation Patterns of the Spruce-Fir Area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park Dorothy Louise Crandall University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Crandall, Dorothy Louise, "Ground Vegetation Patterns of the Spruce-Fir Area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1957. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1624 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Dorothy Louise Crandall entitled "Ground Vegetation Patterns of the Spruce-Fir Area of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Botany. Royal E. Shanks, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: James T. Tanner, Fred H. Norris, A. J. Sharp, Lloyd F. Seatz Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) December 11, 19)7 To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by DorothY Louise Crandall entitled "Ground Vegetation Patterns of the Spruce-Fir Area of the Great Smoky Hountains National Park." I recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Botany. -

THE GENETIC DIVERSITY and POPULATION STRUCTURE of GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS of NATURAL HISTORY and CONSERVATION EFFORTS a Thesis B

THE GENETIC DIVERSITY AND POPULATION STRUCTURE OF GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS OF NATURAL HISTORY AND CONSERVATION EFFORTS A Thesis by NIKOLAI M. HAY Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2017 Department of Biology ! THE GENETIC DIVERSITY AND POPULATION STRUCTURE OF GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS OF NATURAL HISTORY AND CONSERVATION EFFORTS A Thesis by NIKOLAI M. HAY December 2017 APPROVED BY: Matt C. Estep Chairperson, Thesis Committee Zack E. Murrell Member, Thesis Committee Ray Williams Member, Thesis Committee Zack E Murrell Chairperson, Department of Biology Max C. Poole, Ph.D. Dean, Cratis D. Williams School of Graduate Studies ! Copyright by Nikolai M. Hay 2017 All Rights Reserved ! Abstract THE GENETIC DIVERSITY AND POPULATION STRUCTURE OF GEUM RADIATUM: EFFECTS OF NATURAL HISTORY AND CONSERVATION EFFORTS Nikolai M. Hay B.S., Appalachian State University M.S., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Matt C. Estep Geum radiatum is a federally endangered high-elevation rock outcrop endemic herb that is widely recognized as a hexaploid and a relic species. Little is currently known about G. radiatum genetic diversity, population interactions, or the effect of augmentations. This study sampled every known population of G. radiatum and used microsatellite markers to observe the alleles present at 8 loci. F-statistics, STRUCTURE, GENODIVE, and the R package polysat were used to measure diversity and genetic structure. The analysis demonstrates that there is interconnectedness and structure of populations and was able to locate augmented and punitive hybrids individuals within an augmented population. Geum radiautm has diversity among and between populations and suggests current gene flow in the northern populations. -

Introduction to the Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan

SOUTHERN BLUE RIDGE ECOREGIONAL CONSERVATION PLAN Summary and Implementation Document March 2000 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY and the SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN FOREST COALITION Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan Summary and Implementation Document Citation: The Nature Conservancy and Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition. 2000. Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan: Summary and Implementation Document. The Nature Conservancy: Durham, North Carolina. This document was produced in partnership by the following three conservation organizations: The Nature Conservancy is a nonprofit conservation organization with the mission to preserve plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition is a nonprofit organization that works to preserve, protect, and pass on the irreplaceable heritage of the region’s National Forests and mountain landscapes. The Association for Biodiversity Information is an organization dedicated to providing information for protecting the diversity of life on Earth. ABI is an independent nonprofit organization created in collaboration with the Network of Natural Heritage Programs and Conservation Data Centers and The Nature Conservancy, and is a leading source of reliable information on species and ecosystems for use in conservation and land use planning. Photocredits: Robert D. Sutter, The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This first iteration of an ecoregional plan for the Southern Blue Ridge is a compendium of hypotheses on how to conserve species nearest extinction, rare and common natural communities and the rich and diverse biodiversity in the ecoregion. The plan identifies a portfolio of sites that is a vision for conservation action, enabling practitioners to set priorities among sites and develop site-specific and multi-site conservation strategies. -

Microsatellite Markers for the Biogeographically Enigmatic Sandmyrtle (Kalmia Buxifolia, Phyllodoceae: Ericaceae)

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 2019 Microsatellite markers for the biogeographically enigmatic sandmyrtle (Kalmia buxifolia, Phyllodoceae: Ericaceae) Emily L. Gillespie Tesa Madsen‐McQueen Torsten Eriksson Adam Bailey Zack E. Murrell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers Part of the Biology Commons PRIMER NOTE Microsatellite markers for the biogeographically enigmatic sandmyrtle (Kalmia buxifolia, Phyllodoceae: Ericaceae) Emily L. Gillespie1,6 , Tesa Madsen‐McQueen2 , Torsten Eriksson3 , Adam Bailey4 , and Zack E. Murrell5 Manuscript received 5 January 2019; revision accepted 31 January PREMISE: Microsatellite markers were developed for sandmyrtle, Kalmia buxifolia (Ericaceae), 2019. to facilitate phylogeographic studies in this taxon and possibly many of its close relatives. 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Butler University, 4600 Sunset Avenue, Indianapolis, Indiana 46208, USA METHODS AND RESULTS: Forty-eight primer pairs designed from paired-end Illumina MiSeq 2 Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal data were screened for robust amplification. Sixteen pairs were amplified again, but with fluo- Biology, University of California, Riverside, 900 University Avenue, rescently labeled primers to facilitate genotyping. Resulting chromatograms were evaluated Riverside, California 92521, USA for variability using three populations from Tennessee, North Carolina, and New Jersey, USA. -

Federally-Listed Wildlife Species

Assessment for the Nantahala and Pisgah NFs March 2014 Federally-Listed Wildlife Species Ten federally-endangered (E) or threatened (T) wildlife species are known to occur on or immediately adjacent to the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests (hereafter, the Nantahala and Pisgah NFs). These include four small mammals, two terrestrial invertebrates, three freshwater mussels, and one fish (Table 1). Additionally, two endangered species historically occurred on or adjacent to the Forest, but are considered extirpated, or absent, from North Carolina and are no longer tracked by the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program (Table 1). Table 1. Federally-listed wildlife species known to occur or historically occurring on or immediately adjacent to the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests. Common Name Scientific Name Federal Status Small Mammals Carolina northern flying Glaucomys sabrinus coloratus Endangered squirrel Gray myotis Myotis grisescens Endangered Virginia big-eared bat Corynorhinus townsendii Endangered virginianus Northern long-eared bat Myotis septentrionalis Endangered* Indiana bat Myotis sodalis Endangered Terrestrial Invertebrates Spruce-fir moss spider Microhexura montivaga Endangered noonday globe Patera clarki Nantahala Threatened Freshwater Mussels Appalachian elktoe Alasmidonta raveneliana Endangered Little-wing pearlymussel Pegius fabula Endangered Cumberland bean Villosa trabilis Endangered Spotfin chub Erimonax monachus Threatened Species Considered Extirpated From North Carolina American burying beetle Nicrophorous americanus Endangered Eastern cougar Puma concolor cougar Endangered *Pending final listing following the 12-month finding published in the Federal Register, October 2, 2013. Additionally, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) is addressing petitions to federally list two aquatic species known to occur on or immediately adjacent to Nantahala and Pisgah NFs: eastern hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis), a large aquatic salamander, and sicklefin redhorse (Moxostoma species 2), a fish. -

Optimal Survey Windows for Listed Plants 2020

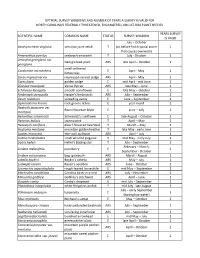

OPTIMAL SURVEY WINDOWS AND NUMBER OF YEARS A SURVEY IS VALID FOR NORTH CAROLINA'S FEDERALLY THREATENED, ENDANGERED, AND AT‐RISK PLANT SPECIES YEARS SURVEY SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME STATUS SURVEY WINDOW IS VALID Aeschynomene virginica sensitive joint‐vetch T July – October 1 July ‐ October Amaranthus pumilus seabeach amaranth T (or before first tropical storm 1 that causes overwash) Amorpha georgiana var. Georgia lead‐plant ARS late April – October 2 georgiana small‐anthered Cardamine micranthera E April ‐ May 1 bittercress Carex impressinervia impressed‐nerved sedge ARS April ‐ May 2 Carex lutea golden sedge E mid April ‐ mid June 2 Dionaea muscipula Venus flytrap ARS late May – June 2 Echinacea laevigata smooth coneflower E late May – October 2 Fimbristylis perpusilla Harper’s fimbristylis ARS July – September 2 Geum radiatum spreading avens E June – September 2 Gymnoderma lineare rock gnome lichen E year round 2 Hedyotis purpurea var. Roan Mountain bluet E June – July 2 montana Helianthus schweinitzii Schweinitz's sunflower E late August – October 2 Helonias bullata swamp pink T April – May 2 Hexastylis naniflora dwarf‐flowered heartleaf T March – May 2 Hudsonia montana mountain golden heather T late May ‐ early June 2 Isoetes microvela thin‐wall quillwort ARS April – July 1 Isotria medeoloides small whorled pogonia T mid May ‐ early July 1 Liatris helleri Heller's blazing star T July – September 2 February – March; Lindera melissifolia pondberry E 2 September ‐ October Lindera subcoriacea bog spicebush ARS March ‐ August 2 Lobelia -

Optimal Survey Windows for At-Risk and Listed Plants of North Carolina

OPTIMAL SURVEY WINDOWS AND NUMBER OF YEARS A SURVEY IS VALID FOR NORTH CAROLINA'S FEDERALLY THREATENED, ENDANGERED, AND AT‐RISK PLANT SPECIES YEARS SURVEY SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME STATUS SURVEY WINDOW IS VALID July – October Aeschynomene virginica sensitive joint‐vetch T (or before first tropical storm 1 that causes overwash) Amaranthus pumilus seabeach amaranth T July ‐ October 1 Amorpha georgiana var. Georgia lead‐plant ARS late April – October 2 georgiana small‐anthered Cardamine micranthera E April ‐ May 1 bittercress Carex impressinervia impressed‐nerved sedge ARS April ‐ May 2 Carex lutea golden sedge E mid April ‐ mid June 2 Dionaea muscipula Venus flytrap ARS late May – June 2 Echinacea laevigata smooth coneflower E late May – October 2 Fimbristylis perpusilla Harper’s fimbristylis ARS July – September 2 Geum radiatum spreading avens E June – September 2 Gymnoderma lineare rock gnome lichen E year round 2 Hedyotis purpurea var. Roan Mountain bluet E June – July 2 montana Helianthus schweinitzii Schweinitz's sunflower E late August – October 2 Helonias bullata swamp pink T April – May 2 Hexastylis naniflora dwarf‐flowered heartleaf T March – May 2 Hudsonia montana mountain golden heather T late May ‐ early June 2 Isoetes microvela thin‐wall quillwort ARS April – July 1 Isotria medeoloides small whorled pogonia T mid May ‐ early July 1 Liatris helleri Heller's blazing star T July – September 2 February – March; Lindera melissifolia pondberry E 2 September ‐ October Lindera subcoriacea bog spicebush ARS March ‐ August 2 Lobelia -

Natural Vegetation of the Carolinas: Classification and Description of Plant Communities of the Far Western Mountains of North Carolina

Natural vegetation of the Carolinas: Classification and Description of Plant Communities of the Far Western Mountains of North Carolina A report prepared for the Ecosystem Enhancement Program, North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources in partial fulfillments of contract D07042. By M. Forbes Boyle, Robert K. Peet, Thomas R. Wentworth, Michael P. Schafale, and Michael Lee Carolina Vegetation Survey Curriculum in Ecology, CB#3275 University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC 27599‐3275 Version 1. April, 2011 1 INTRODUCTION In mid June 2010, the Carolina Vegetation Survey conducted an initial inventory of natural communities along the far western montane counties of North Carolina. There had never been a project designed to classify the diversity of natural upland (and some wetland) communities throughout this portion of North Carolina. Furthermore, the data captured from these plots will enable us to refine the community classification within the broader region. The goal of this report is to determine a classification structure based on the synthesis of vegetation data obtained from the June 2010 sampling event, and to use the resulting information to develop restoration targets for disturbed ecosystems location in this general region of North Carolina. STUDY AREA AND FIELD METHODS From June 13‐20 2010, a total of 48 vegetation plots were established throughout the far western mountains of North Carolina (Figure 1). Focus locations within the study area included the Pisgah National Forest (NF) (French Broad and Pisgah Ranger Districts), the Nantahala NF (Tusquitee Ranger District), and Sandymush Game Land. Target natural communities throughout the week included basic oak‐hickory forest, rich cove forest, northern hardwood and boulderfield forest, chestnut oak forest, montane red cedar woodland, shale slope woodland, montane alluvial slough forest, and low elevation xeric pine forest.