Apple Blossom Time in the Annapolis Valley 1880-1957

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXPLORER Official Visitors Guide

eFREE 2021 Official Visitors Guide Annapolis Rxploroyal & AreaerFREE Special Edition U BEYO D OQW TITEK A Dialongue of Place & D’iversity Page 2, explorer, 2021 Official Visitors Guide Come in and browse our wonderful assortment of Mens and Ladies apparel. Peruse our wide The unique Fort Anne Heritage Tapestry, designed by Kiyoko Sago, was stitched by over 100 volunteers. selection of local and best sellers books. Fort Anne Tapestry Annapolis Royal Kentville 2 hrs. from Halifax Fort Anne’s Heritage Tapestry How Do I Get To Annapolis Royal? Exit 22 depicts 4 centuries of history in Annapolis Holly and Henry Halifax three million delicate needlepoint Royal Bainton's stitches out of 95 colours of wool. It Tannery measures about 18’ in width and 8’ Outlet 213 St George Street, Annapolis Royal, NS Yarmouth in height and was a labor of love 19025322070 www.baintons.ca over 4 years in the making. It is a Digby work of immense proportions, but Halifax Annapolis Royal is a community Yarmouth with an epic story to relate. NOVA SCOTIA Planning a Visit During COVID-19 ANNAPOLIS ROYAL IS CONVENIENTLY LOCATED Folks are looking forward to Fundy Rose Ferry in Digby 35 Minutes travelling around Nova Scotia and Halifax International Airport 120 Minutes the Maritimes. “Historic, Scenic, Kejimkujik National Park & NHS 45 Minutes Fun” Annapolis Royal makes the Phone: 9025322043, Fax: 9025327443 perfect Staycation destination. Explorer Guide on Facebook is a www.annapolisroyal.com Convenience Plus helpful resource. Despite COVID19, the area is ready to welcome visitors Gasoline & Ice in a safe and friendly environment. -

2019 Bay of Fundy Guide

VISITOR AND ACTIVITY GUIDE 2019–2020 BAYNova OF FUNDYScotia’s & ANNAPOLIS VALLEY TIDE TIMES pages 13–16 TWO STUNNING PROVINCES. ONE CONVENIENT CROSSING. Digby, NS – Saint John, NB Experience the phenomenal Bay of Fundy in comfort aboard mv Fundy Rose on a two-hour journey between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Ferries.ca Find Yourself on the Cliffs of Fundy TWO STUNNING PROVINCES. ONE CONVENIENT CROSSING. Digby, NS – Saint John, NB Isle Haute - Bay of Fundy Experience the phenomenal Bay of Fundy in comfort aboard mv Fundy Rose on a two-hour journey between Nova Scotia Take the scenic route and fi nd yourself surrounded by the and New Brunswick. natural beauty and rugged charm scattered along the Fundy Shore. Find yourself on the “Cliffs of Fundy” Cape D’or - Advocate Harbour Ferries.ca www.fundygeopark.ca www.facebook.com/fundygeopark Table of Contents Near Parrsboro General Information .................................. 7 Top 5 One-of-a-Kind Shopping ........... 33 Internet Access .................................... 7 Top 5 Heritage and Cultural Smoke-free Places ............................... 7 Attractions .................................34–35 Visitor Information Centres ................... 8 Tidally Awesome (Truro to Avondale) ....36–43 Important Numbers ............................. 8 Recommended Scenic Drive ............... 36 Map ............................................... 10–11 Top 5 Photo Opportunities ................. 37 Approximate Touring Distances Top Outdoor Activities ..................38–39 Along Scenic Route .........................10 -

Annapolis Basin Bay of Fundy Estuary Profile Annapolis Basin

Bay of Fundy Estuary Profiles Annapolis Basin Bay of Fundy Estuary Profile Annapolis Basin The Annapolis Basin is a sub-basin of the Bay of Fundy along the northwestern shore of Nova Scotia and at the western end of the Annapolis Valley. The Annapolis River is the major water source flowing into the estuary. At the NB mouth of the estuary, a narrow channel known as the Digby Gut connects the 44 NS estuary to the Bay of Fundy. Annapolis Royal and Digby are the main communities along the shore of the estuary, and Kingston-Greenwood is within the catchment area. Near Digby, there is a ferry port that connects to Saint John, New Brunswick. The estuary also hosts a tidal power generating station, which is near Annapolis Royal. The economy within the catchment area is largely driven by agriculture. However, Estuary surface area 104.07 km2 there are also several shellfish and finfish aquaculture tenures, and some Width at estuary mouth 1.85 km commercial fisheries near the mouth of the estuary that largely target Shoreline length 200.63 km invertebrates such as crab, lobster, and clams that inhabit tidal mudflats. The Catchment area 2322.05 km2 extensive tidal mudflats within the estuary are important habitat for Shorebird colonies 2 shorebirds. Within the catchment area there is freshwater habitat for wood Protected area 94.81 km2 turtles, and two protected areas that overlap with the landward boundary of Paved roads 1028 km the estuary. Although the upper valley is primarily agricultural land, much of Aquaculture leases 10 the rest of the catchment area is covered by forest. -

They Planted Well: New England Planters in Maritime Canada

They Planted Well: New England Planters in Maritime Canada. PLACES Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia, 9, 10, 12 Amherst Township, Nova Scotia, 124 Amherst, Nova Scotia, 38, 39, 304, 316 Andover, Maryland 65 Annapolis River, Nova Scotia, 22 Annapolis Township, Nova Scotia, 23, 122-123 Annapolis Valley, Nova Scotia, 10, 14-15, 107, 178 Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, 20, 24-26, 28-29, 155, 258 Annapolis Gut, Nova Scotia, 43 Annapolis Basin, Nova Scotia, 25 Annapolis-Royal (Port Royal-Annapolis), 36, 46, 103, 244, 251, 298 Atwell House, King's County, Nova Scotia, 253, 258-259 Aulac River, New Brunswick, 38 Avon River, Nova Scotia, 21, 27 Baie Verte, Fort, (Fort Lawrence) New Brunswick, 38 Barrington Township, Nova Scotia, 124, 168, 299, 315, Beaubassin, New Brunswick (Cumberland Basin), 36 Beausejour, Fort, (Fort Cumberland) New Brunswick, 17, 22, 36-37, 45, 154, 264, 277, 281 Beaver River, Nova Scotia, 197 Bedford Basin, Nova Scotia, 100 Belleisle, Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, 313 Biggs House, Gaspreau, Nova Scotia, 244-245 Blomidon, Cape, Nova Scotia, 21, 27 Boston, Massachusetts, 18, 30-31, 50, 66, 69, 76, 78, 81-82, 84, 86, 89, 99, 121, 141, 172, 176, 215, 265 Boudreau's Bank, (Starr's Point) Nova Scotia, 27 Bridgetown, Nova Scotia, 196, 316 Buckram (Ship), 48 Bucks Harbor, Maine, 174 Burton, New Brunswick, 33 Calkin House, Kings County, 250, 252, 259 Camphill (Rout), 43-45, 48, 52 Canning, Nova Scotia, 236, 240 Canso, Nova Scotia, 23 Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, 40, 114, 119, 134, 138, 140, 143-144 2 Cape Cod-Style House, 223 -

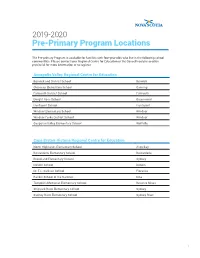

2019-2020 Pre-Primary Program Locations

2019-2020 Pre-Primary Program Locations The Pre-primary Program is available for families with four-year-olds who live in the following school communities. Please contact your Regional Centre for Education or the Conseil scolaire acadien provincial for more information or to register. Annapolis Valley Regional Centre for Education Berwick and District School Berwick Glooscap Elementary School Canning Falmouth District School Falmouth Dwight Ross School Greenwood Hantsport School Hantsport Windsor Elementary School Windsor Windsor Forks District School Windsor Gasperau Valley Elementary School Wolfville Cape Breton-Victoria Regional Centre for Education North Highlands Elementary School Aspy Bay Boularderie Elementary School Boularderie Brookland Elementary School Sydney Donkin School Donkin Dr. T.L. Sullivan School Florence Rankin School of the Narrows Iona Tompkins Memorial Elementary School Reserve Mines Shipyard River Elementary School Sydney Sydney River Elementary School Sydney River 1 Chignecto-Central Regional Centre for Education West Colchester Consolidated School Bass River Cumberland North Academy Brookdale Great Village Elementary School Great Village Uniacke District School Mount Uniacke A.G. Baillie Memorial School New Glasgow Cobequid District Elementary School Noel Parrsboro Regional Elementary School Parrsboro Salt Springs Elementary School Pictou West Pictou Consolidated School Pictou Scotsburn Elementary School Scotsburn Tatamagouche Elementary School Tatamagouche Halifax Regional Centre for Education Sunnyside Elementary School Bedford Alderney Elementary School Dartmouth Caldwell Road Elementary School Dartmouth Hawthorn Elementary School Dartmouth John MacNeil Elementary School Dartmouth Mount Edward Elementary School Dartmouth Robert K. Turner Elementary School Dartmouth Tallahassee Community School Eastern Passage Oldfield Consolidated School Enfield Burton Ettinger Elementary School Halifax Duc d’Anville Elementary School Halifax Elizabeth Sutherland Halifax LeMarchant-St. -

Municipal Property Taxation in Nova Scotia

MUNICIPAL PROPERTY TAXATION IN NOVA SCOTIA A report by Harry Kitchen and Enid Slack for the Property Valuation Services Corporation Union of Nova Scotia Municipalities Association of Municipal Administrators April 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 4 A. Criteria for Evaluating the Property Tax 12 B. Background on Municipal Finance in Nova Scotia 13 C. Inter-provincial Comparison of Property Taxation 17 a. General Assessment Categories and Tax Rate Structure 17 b. Property Taxes and School Funding 18 c. Assessment Administration 18 d. Frequency of Assessment 19 e. Limits on the Impact of a Reassessment 20 f. Exemptions 20 g. Payments in Lieu of Taxes 21 h. Treatment of Machinery and Equipment 22 i. Treatment of Linear Properties 22 j. Business Occupancy Taxes 23 k. Property Tax Relief Programs 23 l. Property Tax Incentives 24 D. Property Taxation in Nova Scotia 26 a. Assessment Base 26 b. Tax Rates 34 E. Concerns and Issues Raised about Property Taxes in Nova Scotia 39 a. Assessment Issues 39 1. Area-based or value-based assessment 39 2. Exempt properties and payments in lieu 42 3. Lag between assessment date and implementation 44 4. Volatility 45 b. Property Taxation Issues 50 5. Capping 50 6. Commercial versus residential property taxation 60 7. Tax incentives – should property taxes be used to stimulate economic development? 70 8. Should provincial property taxes be used to fund education? 72 9. Tax treatment of agricultural and resource properties no longer used for those purposes 74 10. Urban/rural tax differentials 76 F. Summary of Recommendations 77 2 References 79 Appendix A: Inter-provincial Comparisons 82 Appendix B: Stakeholder Consultations 96 3 Executive Summary The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the current property tax system in Nova Scotia and suggest improvements. -

Rail-To-Trail Conversion – Windsor and Hantsport Railway

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 14.1.5 Halifax Regional Council January 30, 2018 TO: Mayor Savage and Members of Halifax Regional Council SUBMITTED BY: Jacques Dubé, Chief Administrative Officer DATE: December 5, 2017 SUBJECT: Rail‐to‐Trail Conversion – Windsor & Hantsport Railway ORIGIN At the September 5, 2017 meeting of Regional Council a motion was passed to request a staff report on the feasibility of developing an active transportation facility on the corridor of the Windsor and Hantsport Railway (W&HR) that includes information on the potential cost, property permission options, implementation options, and connectivity to the active transportation network in Halifax and the Municipality of the District of East Hants. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY The Halifax Charter section 79(1)(ah) states that The Council may expend money required by the Municipality for playgrounds, trails, including trails developed, operated or maintained pursuant to an agreement made under clause 73(c), bicycle paths, swimming pools, ice arenas, and other recreation facilities. RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that Halifax Regional Council: 1) Direct staff to maintain communication with municipalities along the Windsor and Hantsport Rail Spur corridor on this issue; 2) Monitor any changes in the ownership and operation of the facility; and 3) Send a letter to CN and the Canadian Transportation Agency that expresses HRM’s interest in acquiring the portions of this corridor in the Municipality for a rails-to-trails facility, should it become available. Rail-to-Trail Conversion – Windsor & Hantsport Railway Council Report - 2 - January 30, 2018 BACKGROUND A rail spur from Windsor to Windsor Junction was built as the Windsor Branch of the Nova Scotia Railway in 1858. -

Internal Stratigraphy of the Jurassic North Mountain Basalt, Southern Nova Scotia

Report of Activities 2001 69 • Internal Stratigraphy of the Jurassic North Mountain Basalt, Southern Nova Scotia D. J. Kontak Introduction sediments are exposed, only 9 m of Scots Bay Formation remain as remnant inliers along the The Jurassic (201 Ma, Hodych and Dunning, 1992) Scots Bay coastline (De Wet and Hubert, 1989). North Mountain Basalt (NMB; also referred to as the North Mountain Fonnation) fonns a prominent The NMB outcrops along the Bay of Fundy in cuesta along the southern coastline of the Bay of southern mainland Nova Scotia and is Fundy. These continental, tholeiitic basalt flows exceptionally well exposed along the coastline and have played an important role in the geological inland along river valleys (Fig. 1). Topographic heritage of the province by: (l) hosting some ofthe relief of the area bounding the Bay of Fundy earliest mineral resources exploited (e.g. Cu, Fe), reflects the distribution of the underlying massive (2) contributing to the character of zeolite basalt flows. No more obvious is this than along mineralogy (e.g. type locality for mordenite; How, the Annapolis Valley area where the west side of 1864), (3) fonning part of the Fundy Rift Basin, an the valley is composed of massive, fresh basalt of important part of the Mesozoic evolution of eastern the lower flow unit of the NMB. The proximity of North America, and (4) filling an important niche the area on the north side of the Bay of Fundy to in the aggregate operations of the province. Despite the east-west Cobequid-Chedabucto Fault Zone has the importance of the NMB there has been resulted in structural modifications to the otherwise relatively little recent work devoted to defining and simple stratigraphy of the NMB. -

• Isaak Walton Killam & Alfred C. Fuller

• Isaak Walton Killam & Alfred C. Fuller: Whereas Isaak Walton Killam, born on Parade Street in Yarmouth, and protégé of Lord Beaverbrook, became one of the most successful Canadian businessmen of the 20th Century: Born in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, Killam rose from paper boy in Yarmouth to become one of Canada's wealthiest individuals. As a young banker with the Union Bank of Halifax, Killam became close friends with John F. Stairs and Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook) who put Killam in charge of his Royal Securities. In 1919, Killam bought out Aitken and took full control of the company. Killam's business dealings primarily involved the financing of large pulp and paper and hydro-electric projects throughout Canada and Latin America. Killam was believed to be the richest man in Canada at the time. One of his larger projects in his native province was the creation of the Mersey Paper Company Ltd. and its related electrical generating stations and shipping fleet. In 1922, he married Dorothy Brooks Johnston. Notwithstanding his prodigious financial accomplishments, Killam was a very reserved man who eschewed publicity and was virtually unknown outside a small circle of close acquaintances. Killam died in 1955 at his Quebec fishing lodge. By then, he was considered to be the richest man in Canada. Having no children, Killam and his wife devoted the greater part of their wealth to higher education in Canada. The Killam Trusts, established in the will of Mrs. Killam, are held by five Canadian universities: the University of British Columbia, University of Alberta, University of Calgary, Dalhousie University and McGill University. -

Annapolis Valley

2021-2022 PRE-DOCTORAL RESIDENCY IN PSYCHOLOGY MENTAL HEALTH AND ADDICTIONS NOVA SCOTIA HEALTH - ANNAPOLIS VALLEY Revised August 2020 2 1. ABOUT ANNAPOLIS VALLEY 3 2. ABOUT NOVA SCOTIA HEALTH AUTHORITY 4 2.1 PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES AND THE DISCIPLINE OF PSYCHOLOGY 4 2.2. Supervising Psychologists 5 3. PRE-DOCTORAL RESIDENCY IN PSYCHOLOGY 7 3.1 PURPOSE 7 3.2 STRUCTURE 7 4. PRIMARY TRACKS AND ROTATIONS 8 4.1. Adult Mental Health Track 8 4.2. Child and Youth Mental Health Track 12 5. SUPERVISION 15 5.1. Standards for Supervision 15 6. EVALUATION 16 7. EMPLOYMENT AND WORK LOAD PROCEDURES 17 7.1. HOSPITAL/CLINIC POLICY 17 7.2. STIPEND AND BENEFITS 17 7.3. OVERTIME POLICY 17 7.4. RESOURCES 17 8. APPLICATION PROCEDURE 18 3 1. ABOUT ANNAPOLIS VALLEY The scenic Annapolis Valley is located within the western peninsula of Nova Scotia and spans approximately 130 km from the picturesque town of Wolfville (home of Acadia University) to the historical and seaside towns of Annapolis Royal and Digby. The pre- doctoral residency program is primarily located in the town of Kentville, a 10- minute drive from Wolfville. Within and around the towns of Wolfville and Kentville can be found a variety of cultural, sporting and recreational activities including professional and community theatre, music, cinema, university sports teams, downhill skiing, golf, and fine and casual dining. Local farms and markets provide exceptional fresh food and quaint seasonal activities (e.g., apple picking, pumpkin patches, corn mazes), while the growing winery, cidery, and microbrewery scenes provide many tasting options for connoisseurs of such adult beverages. -

Groundwater Resources and Hydrogeology of the Windsor-Hantsport-Walton Area, Nova Scotia

PROVINCE OF NOVA SCOTIA DEPARTMENT OF MINES Groundwater Section Report 69- 2 GROUNDWATER RESOURCES AND HYDROGEOLOGY of the W I NDSOR- HANTSPORT- WALTON AREA, NOVA SCOTIA by Peter C. Trescott HON. PERCY GAUM J.P. NOWLAN, Ph.D. MINISTER DEPUTY MI NI STE R Halifax, Nova Scotia 1969 PREFACE The Nova Scotia Department of Mines initiated in 1964 an extensive program to evaluate the groundwater resources of the Province of Nova Scotia. This report on the hydrogeology of the Windsor- Hantsport-Walton area is an ex- tension of the Annapolis-C o r n w a I I i s Val ley study reported in Department of Mines Memoir 6. The field work for this study was carried out during the summer of 1968 by the Groundwater Section, Nova Scotia Department of Mines, and is a joint undertaking between the Canada Department of Forestry and Rural Development and the Province of Nova Scotia (ARDA project No. 22042). Recently the ad- ministration of the A R D A Act was t r a n s f e rr e d to the Canada Department of Regional Economic Expansion. It should be pointed out that many individuals and other government agencies cooperated in supplying much valuable i n f o rma t i on and assistance throughout the period of study. To list a few: Dr. J. D. Wright, Director, Geological Division and the staff of the Mineral Resources Section, Nova Scotia Department of Mines, Mr. J. D. McGinn, Clerk and Treasurer, Town of Hants- port, and the Nova Scotia Agricultural College at Truro. -

New Minas Detachment: Structure and Organiztion

Atlantic Institute of Criminology ROYAL CANADIAN MOUNTED POLICE NEW MINAS DETACHMENT: STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZTION Anthony Thomson and Lynda Clairmont 1992 Occasional Paper Series The authors would like to acknowledge Staff Sergeant Ralph Humble and Staff Sergeant (Ret.) Paul Fraser, and members of the New Minas Detachment for their cooperation and the Donner Canadian Foundation for research funding TABLE OF CONTENTS I Introduction 1. Policing Styles 2. Kings County and New Minas: A Snapshot Section II 1. An Overview of the Development of R.C.M.P. Policing in Nova Scotia 2. Style of Policing 3. The New Minas Detachment Area 4. Recruitment 5. Promotions and Transfers 6. The Uniform Constable-Generalist 7. Autonomy and Working Conditions 8. The General Investigative Services (G.I.S.) 9. Crime Prevention/ Police-Community Relations (CP/PCR) 10. Complaints 11. Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) 12. Highway Patrol 13. Drugs 14. Forensic Identification Unit (IDENT.) 15. Clerical Staff 16. The Divisional Bureaucracy 17. Crown Prosecutors 18. Private Policing Section III 1. Police Productivity 2. Criminal Code Offences A. Total Offences B. Five-Year Variation C. Violent Crime D. Property Crime E. Other Criminal Code Offences F. Drug Offences Bibliography Appendix - Clearance Rates, 1980-1989 I. INTRODUCTION1 Policing may be one of the most frequently studied occupations in North America. This attention derives from a number of sources, not the least of which is the inherent ambiguity of policing in a liberal democratic state. Most studies, however, have concentrated on the experience of police departments in large urban settings (Ericson, 1982). In Nova Scotia, Richard Apostle and Philip Stenning conducted a research study on public policing in the province under the auspices of the Royal Commission on the Donald Marshall, Jr., Prosecution (1988).