Humanist Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short Course on Humanism

A Short Course On Humanism © The British Humanist Association (BHA) CONTENTS About this course .......................................................................................................... 5 Introduction – What is Humanism? ............................................................................. 7 The course: 1. A good life without religion .................................................................................... 11 2. Making sense of the world ................................................................................... 15 3. Where do moral values come from? ........................................................................ 19 4. Applying humanist ethics ....................................................................................... 25 5. Humanism: its history and humanist organisations today ....................................... 35 6. Are you a humanist? ............................................................................................... 43 Further reading ........................................................................................................... 49 33588_Humanism60pp_MH.indd 1 03/05/2013 13:08 33588_Humanism60pp_MH.indd 2 03/05/2013 13:08 About this course This short course is intended as an introduction for adults who would like to find out more about Humanism, but especially for those who already consider themselves, or think they might be, humanists. Each section contains a concise account of humanist The unexamined life thinking and a section of questions -

Read CDPRG Chairman Crispin Blunt's Letter to the Prime Minister

The Conservative Drug Policy Reform Group, Limited Suite 15.17 Citibase, 15th Floor Millbank Tower 21-24 Millbank, Westminster London SW1P 4QP The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP The Prime Minister 10 Downing Street London SW1A 2AA 20 November 2020 Dear Prime Minister, As Chairman of the Conservative Drug Policy Reform Group, I am writing today with a comprehensive set of recommendations prepared by the CDPRG research team, to secure the future of the UK’s cannabidiol (CBD) industry. Though nascent, this industry is already valued at £300 million and it is predicted to grow to around £1 billion by 2025, equivalent to the entirety of the UK’s herbal supplement market in 2016. I am sure you will agree with me that this projected market growth, and the jobs, investment and R&D it attracts, needs safeguarding and stimulating rather than inhibiting. This fulfilment depends on the practicality of the legislations safeguarding this burgeoning industry, which is why I am writing to strongly recommend that the UK votes in favour of recommendations to be proposed on 02 December 2020 by the World Health Organisation at the 53rd United Nations Session on the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND), of which the UK is a signatory. The WHO recommends adding the following footnote to the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, to read: "Preparations containing predominantly cannabidiol and not more than 0.2 percent of delta-9- tetrahydrocannabinol [THC] are not under international control”. This harmonises with a ruling issued this week from the European Union that member states may not prohibit the marketing of CBD lawfully produced in other member states. -

Issue 4, 2019 Special Issue on Prevent

Issue 4, 2019 Special Issue on Prevent Co-edited by Sukhwant Dhaliwal, Rebecca Durand, Stephen Cowden Inside this issue: Feature Articles Poetry by Dean Atta Artwork on Xenofon Kavvadias Book and Conference Reviews ISSN: 2398-4139 Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies, University of Warwick Image 1: Holocauston, detail © Xenofon Kavvadias. All Rights Reserved. Feminist Dissent Feminist Dissent – Issue 4 Special Issue on Prevent Co-edited by Sukhwant Dhaliwal, Rebecca Durand, Stephen Cowden Table of Contents All artworks are by Xenofon Kavvadias. Cover Image Image 2 Editorial: A Polarised Debate – Stephen Cowden, Sukhwant Dhaliwal, Rebecca Durand (p. 1-15) Image 3 Respecting and Ensuring Rights: Feminist Ethics for a State Response to Fundamentalism Sukhwant Dhaliwal (p. 16-54) Image 4 Prevent: Safeguarding and the Gender Dimension Pragna Patel (p. 55-68) Image 5 Walking the Line: Prevent and the Women’s Voluntary Sector in a Time of Austerity Yasmin Rehman (p. 69-87) Image 6 Poetry – ‘The Black Flamingo’ Dean Atta (p. 88-90) Image 7 Feminist Dissent 2019 (4) i Feminist Dissent Safeguarding or Surveillance? Social Work, Prevent and Fundamentalist Violence Stephen Cowden and Jonathan Picken (p. 91-131) Image 8 Jihadi Brides, Prevent and the Importance of Critical Thinking Skills Tehmina Kazi (p. 132-145) Image 9 Victims, Perpetrators or Protectors: The Role of Women in Countering Terrorism Hifsa Haroon-Iqbal (p. 146-157) Image 10 Poetry – ‘I come from’ Dean Atta (p. 158-159) Image 11 The Prevent Strategy’s impact on social relations: a report on work in two local authorities David Parker, David Chapot and Jonathan Davis (p. -

Open PDF 113KB

Written evidence submitted by Humanists UK (IRN0004) ABOUT HUMANISTS UK At Humanists UK, we want a tolerant world where rational thinking and kindness prevail. We work to support lasting change for a better society, championing ideas for the one life we have. Since 1896, our work has been helping people be happier and more fulfilled. By bringing non-religious people together we help them develop their own views and an understanding of the world around them. Together with our partners Humanist Society Scotland, we speak for 100,000 members and supporters and over 100 members of the All-Party Parliamentary Humanist Group. Through our ceremonies, pastoral support, education services, and campaigning work, we advance free thinking and freedom of choice so everyone can live in a fair and equal society. We work closely with Humanists International, founded in 1952 as the global representative body of the humanist movement, with over 170 member organisations in over 70 countries, and of which our Chief Executive is also the current President. We are also a member of the European Humanist Federation (EHF). We have good relations with the UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO), meeting regularly with ministers and officials. We are on the steering group of the UK Freedom of Religion or Belief (FoRB) Forum and are an active member of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on FoRB. We are accredited at the UN Human Rights Council – the only national humanist group to hold such accreditation – and make interventions there every session. We contribute annually to Humanists International’s Freedom of Thought Report1; and co-founded the End Blasphemy Laws campaign,2 which has successfully prompted ten countries to repeal their blasphemy laws since it was founded in 2015. -

LGBT+ Conservatives Annual Report 2020.Pdf

LGBT+ CONSERVATIVES TEAM April 2019 - July 20201 OFFICERS CHAIRMAN - Colm Howard-Lloyd DEPUTY CHAIRMAN - John Cope HONORARY SECRETARY - Niall McDougall HONORARY TREASURER - Cllr. Sean Anstee CBE VICE-CHAIRMAN CANDIDATES’ FUND - Cllr. Scott Seaman-Digby VICE-CHAIRMAN COMMUNICATIONS - Elena Bunbury (resigned Dec 2019) VICE-CHAIRMAN EVENTS - Richard Salt MEMBERSHIP OFFICER - Ben Joce STUDENT OFFICER - Jason Birt (resigned Sept 2019) GENERAL COUNCIL Cllr. Andrew Jarvie Barry Flux David Findlay Dolly Theis Cllr. Joe Porter Owen Meredith Sue Pascoe Xavier White REGIONAL COORDINATORS EAST MIDLANDS - David Findlay EAST OF ENGLAND - Thomas Smith LONDON - Charley Jarrett NORTH EAST - Barry Flux SCOTLAND - Andrew Jarvie WALES - Mark Brown WEST MIDLANDS - John Gardiner YORKSHIRE AND THE HUMBER - Cllr. Jacob Birch CHAIRMAN’S REPORT After a decade with LGBT+ Conservatives, more than half of them in the chair, it’s time to hand-on the baton I’m not disappearing completely. One of my proudest achievements here has been the LGBT+ Conservatives Candidates’ Fund, which has supported so many people into parliament and raised tens of thousands of pounds. As the fund matures it is moving into a new governance structure, and I hope to play a role in that future. I am thrilled to be succeeded by Elena Bunbury. I know that she will bring new energy to the organisation, and I hope it will continue to thrive under her leadership. I am so grateful to everyone who has supported me on this journey. In particular Emma Warman, Matthew Green and John Cope who have provided wise counsel as Deputy Chairman. To Sean Anstee who has transformed the finances of the organisation. -

The Prime Minister, HC 833

Liaison Committee Oral evidence: The Prime Minister, HC 833 Tuesday 20 December 2016 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 20 Dec 2016. Watch the meeting Members present: Mr Andrew Tyrie (Chair); Hilary Benn; Mr Clive Betts; Crispin Blunt; Andrew Bridgen; Sir William Cash; Yvette Cooper; Meg Hillier; Mr Bernard Jenkin; Dr Julian Lewis; Stephen Metcalfe; Mr Laurence Robertson; Dame Rosie Winterton; Pete Wishart; Dr Sarah Wollaston; Mr Iain Wright. Questions 1-129 Witness [I]: Rt Hon Mrs Theresa May Examination of witness Witness: Rt Hon Mrs Theresa May Q1 Chair: Prime Minister, thank you very much for coming to give evidence to us this afternoon. We are very grateful, and I think Parliament is also very grateful, that you are agreeing to do these sessions. Could I just have confirmation that you are going to continue the practice of your predecessor of three a year? Mrs May: Yes, indeed, Chairman. I am happy to do three attendances at this Committee a year. Q2 Chair: Logically, bearing in mind the very big events likely to take place at the end of March, it might be sensible to push scrutiny of the triggering, or proposed triggering, of article 50, and any accompanying Government documents, to after the spring recess. Then we will have two meetings: one right at the beginning and one towards the end of the summer session. Mrs May: That may very well be sensible, Chairman. I suggest that perhaps the Clerk and my office will be able to talk about possible dates. Obviously the Committee will have a view as to when they wish to do it. -

DOWNLOAD 2019 UK Audited Accounts

H. \I-t Hurnanists INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONAL HUMANIST AND ETHICAL UNION (operating as HUMANISTS INTERNAIIONAL) FINANGIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2019 COMPANY NUMBER FC O2O6r',2 Humanists lnternational is a trading name of the lntemational Humanist and Ethical Union. INTERNATIONAL HUMANIST AND ETHICAL UNION REPORT OF THE DIRECTORS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2019 The Directors of the lnternational Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU), operating as Humanists lnternational, present their annual report with the annualaccounts of the company for the year ended 31st December 2019. The accounts have been prepared in accordance with the accounting policies set out in Note 1 and comply with current statutory requirements. IHEU is the world federation of organizations making up the global humanist movement, inclusive of all nontheistic traditions such as humanist, atheist, rationalist, secularist, laique, ethical culture, freethought, and skeptic. We want a secular world in which human rights are respected and everyone is able to live a life of dignity. We work to build and represent the global humanist movement that defends human rights and promotes Humanist values world-wide. Our Aims are: o We will have successful and sustainable member organisations in every part of the world o We will create a coordinated global movement by supporting and developing our network o We will influence and shape international and regional government policies o We will have sufficient reputation, resources, and effectiveness to achieve our objectives LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE DETAILS The IHEU is a Membership Corporation pursuant to the Membership Corporation law of the State of New York. lt is registered in England and Wales under the Companies Act as an overseas company having established a place of business in England and Wales. -

Humanism and Christianity: Shared Values?

Shipton et al.: Humanism and Christianity: Shared Values? WARREN SHIPTON, YOUSSRY GUIRGUIS, AND NOLA TUDU Humanism and Christianity: Shared Values? Introduction The word humanism is derived from the Latin humanitas that originally meant the study of human nature. The idea was to elevate humanity with a focus on human dignity and potential through education (Ritchie and Spencer 2014:15, 16). The meaning attributed to the word humanism, in its broadest sense, allowed Christians and non-believers initially to oc- cupy common territory (64-78). In the early-middle Christian era, some thinkers sought to acquaint themselves with the achievements, literature, and thought of past civilizations, particularly Greek, with a view to rec- onciling theology with the philosophy of the classical philosophers (New World Encyclopedia n.d.; Odom 1977:126-128, 183-186). Outside Christian circles, elements supportive of the pre-eminence of human thought and abilities have long been seen among philosophers; however, not all forms of humanism were atheistic, as seen in Confucian thought (Gupta 2000:8- 12). There also are those who have been called “religious” or “spiritual” humanists (Eller 2010:10). The Medieval civilization that followed the collapse of the Roman Em- pire (AD 476) was marked by the rule of kings with nobles supporting the king in return for privileges. The majority of the population existed in serfdom; the Church reigned supreme. A change came in the 14th century helped by the fact that famine and disease created disaster. The abuses in the Church and the pessimism prevalent in society created a climate for change in Europe. -

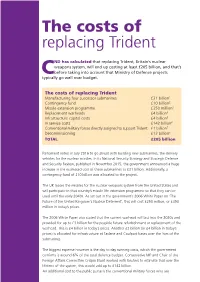

The Costs of Replacing Trident

The costs of replacing Trident ND has calculated that replacing Trident, Britain’s nuclear weapons system, will end up costing at least £205 billion, and that’s Cbefore taking into account that Ministry of Defence projects typically go well over budget. The costs of replacing Trident Manufacturing four successor submarines £31 billion 1 Contingency fund £10 billion 2 Missile extension programme £350 million 3 Replacement warheads £4 billion 4 Infrastructure capital costs £4 billion 5 In service costs £142 billion 6 Conventional military forces directly assigned to support Trident £1 billion 7 Decommissioning £13 billion 8 TOTAL £205 billion Parliament voted in July 2016 to go ahead with building new submarines, the delivery vehicles for the nuclear missiles. In its National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review, published in November 2015, the government announced a huge increase in the estimated cost of these submarines to £31 billion. Additionally, a contingency fund of £10 billion was allocated to the project. The UK leases the missiles for the nuclear weapons system from the United States and will participate in that country’s missile life extension programme so that they can be used until the early 2040s. As set out in the government’s 2006 White Paper on ‘The Future of the United Kingdom's Nuclear Deterrent’ , this will cost £250 million, or £350 million in today’s prices. The 2006 White Paper also stated that the current warhead will last into the 2020s and provided for up to £3 billion for the possible future refurbishment or replacement of the warhead. -

Reform of the Gender Recognition Act - Government Consultation

REFORM OF THE GENDER RECOGNITION ACT - GOVERNMENT CONSULTATION Response from LGBT Humanists, July 2018 ABOUT LGBT HUMANISTS For over 30 years LGBT Humanists has promoted humanism as a rational, naturalistic worldview that trusts the scientific method as the most reliable route to truth and encourages a moral and ethical life based on logic, reason, and compassion. We campaign for equality, particularly relating to sexual orientation and identity – both in the UK and internationally. LGBT Humanists is a volunteer-led section of Humanists UK. Humanists UK advances free thinking and promotes humanism to create a tolerant society where rational thinking and kindness prevail. Its work brings non-religious people together to develop their own views, helping people be happier and more fulfilled in the one life we have. Through its ceremonies, education services, and community and campaigning work, it strives to create a fair and equal society for all. Are you responding as an individual or an organisation? Organisation Full name or organisation’s name LGBT Humanists Phone number 0207 324 3060 Address c/o Humanists UK 39 Moreland Street London Postcode EC1V 8BB Email [email protected] The Government would like your permission to publish your consultation response. Any responses will be treated in accordance with Section 22 of the Gender Recognition Act. This provides protection for the privacy of a person who has applied for and/or obtained a Gender Recognition Certificate by making it a criminal offence to disclose information acquired in an official capacity about a person’s gender history or about their application to the Panel, unless a specific exception applies. -

THE CELEBRATION OP MARRIAGE in CANADA a Comparative Study

538 THE CELEBRATION OP MARRIAGE IN CANADA A Comparative Study of Civil and Canon Law outside of the Province of Quebec by Leo G. iiinz, O.S.t. St. Peter's Abbey, Muenater, bask. A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Canon Law of the Catholic University of Ottawa in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Canon Law • -N " . • ^ °« THF CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OP OTTAWA -0:;?/g Ottawa, Ontario TtU •^ '\ 1953 B»tlOTH*QU<:S * %*,y of O** UMI Number: DC53897 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53897 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI48106-1346 DEDICATED TO THE PIONEER MONKS OF ST. PETER'S ABBEY ON THE OCCASION OF THE GOLDEN JUBILEE OF FOUNDATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages FOREWORD Viii ABBREVIATIONS xii Chapter 1. PRELIMINARY DISCUSSION 1 Article 1. The law ;-T0vernin»: the celebration of marriage 1 Article 2. Provincial powers ever marriage 3 Article 3. Invalidating force of statutory requirements. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit

RECORD NO. 17-15769 Case: 17-15769 Date Filed: 04/24/2018 Page: 1 of 48 In The United States Court Of Appeals For The Eleventh Circuit DAVID WILLIAMSON, CHASE HANSEL, KEITH BECHER, RONALD GORDON, JEFFERY KOEBERL, CENTRAL FLORIDA FREETHOUGHT COMMUNITY, SPACE COAST FREETHOUGHT ASSOCIATION, HUMANIST COMMUNITY OF THE SPACE COAST, Plaintiffs – Appellees – Cross Appellants, v. BREVARD COUNTY, Defendant – Appellant – Cross Appellee. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA ______________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE AMERICAN HUMANIST ASSOCIATION, UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST ASSOCIATION, AND AMERICAN ETHICAL UNION IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES – CROSS APPELLANTS ______________ Monica L. Miller AMERICAN HUMANIST ASSOCIATION 1821 Jefferson Place, NW Washington, DC 20036 (202) 238-9088 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae GibsonMoore Appellate Services, LLC 206 East Cary Street ♦ P.O. Box 1406 (23218) ♦ Richmond, VA 23219 (804) 249- 7770 ♦ www.gibsonmoore.net Case: 17-15769 Date Filed: 04/24/2018 Page: 2 of 48 CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS AND CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Pursuant to Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure 26.1 and 11th Circuit Rule 26.1-1, amici curiae, the American Humanist Association, Unitarian Universalist Association, and American Ethical Union make the following disclosure: Each is a nonprofit membership association, exempt from taxation under 26 U.S.C. § 501(c)(3). Each has no parent or publicly held company owning ten percent or more of the corporation. OTHER ORGANIZATIONS Amici further certify that the following persons and entities have or may have an interest in the outcome of this appeal, as previously provided to the Court by Brevard County: 1.