An Inquiry Into Portland's Canine Quandary: Recommendations for a Citywide Off-Leash Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF File Parks Capital and Planning Investments

SWNI Commissioner Amanda Fritz Interim Director Kia Selley INVESTMENTS IN SOUTHWEST NEIGHBORHOODS, INC. ANNOUNCED 2013-2018 August 2018 | Since 2013, Commissioner Amanda Fritz and Portland Parks & Recreation (PP&R) have allocated over $38M in park planning and capital investments in the Southwest Neighborhoods, Inc. coalition area. Funded by System Development Charges (SDCs), the Parks Replacement Bond (Bond), General Fund (GF), and in some cases matched by other partners, these investments grow, improve access to, or help maintain PP&R parks, facilities, and trails. Questions? Please call Jennifer Yocom at 503-823-5592. CAPITAL PROJECTS, ACQUISITIONS & PLANNING #1 APRIL HILL PARK BOARDWALK AND TRAIL Completed: Winter 2017 Investment: $635K ($498K SDCs; $83K Metro; $25K neighborhood #5 PORTLAND fundraising; $19K PP&R Land Stewardship; $10K BES) OPEN SPACE SEQUENCE Info: New boardwalks, bridges, trails; improves access, protects wetland. #2 DUNIWAY (TRACK & FIELD) #2 DUNIWAY PARK TRACK & FIELD DONATION #4 MARQUAM, #8 SOUTH Completed: Fall 2017 TERWILLIGER, WATERFRONT GEORGE HIMES Investment: Donation of full renovations provided by Under Armour (ACQUISITION & Info: Artificial turf improvement and track re-surfacing. RESTORATION) #3 MARSHALL PARK PLAYGROUND & ACQUISITION Completed: Summer 2015 | 2018 Investment: $977K (Play Area - $402K [$144K OPRD, $257K SDCs] + #11 RIEKE (FIELD) Acquisition - $575K [$450K SDCs, $125K Metro Local Share]) #6 Info: Playground, access to nature and seating improvements | two- #12 GABRIEL RED #9 WILLAMETTE -

District Background

DRAFT SOUTHEAST LIAISON DISTRICT PROFILE DRAFT Introduction In 2004 the Bureau of Planning launched the District Liaison Program which assigns a City Planner to each of Portland’s designated liaison districts. Each planner acts as the Bureau’s primary contact between community residents, nonprofit groups and other government agencies on planning and development matters within their assigned district. As part of this program, District Profiles were compiled to provide a survey of the existing conditions, issues and neighborhood/community plans within each of the liaison districts. The Profiles will form a base of information for communities to make informed decisions about future development. This report is also intended to serve as a tool for planners and decision-makers to monitor the implementation of existing plans and facilitate future planning. The Profiles will also contribute to the ongoing dialogue and exchange of information between the Bureau of Planning, the community, and other City Bureaus regarding district planning issues and priorities. PLEASE NOTE: The content of this document remains a work-in-progress of the Bureau of Planning’s District Liaison Program. Feedback is appreciated. Area Description Boundaries The Southeast District lies just east of downtown covering roughly 17,600 acres. The District is bordered by the Willamette River to the west, the Banfield Freeway (I-84) to the north, SE 82nd and I- 205 to the east, and Clackamas County to the south. Bureau of Planning - 08/03/05 Southeast District Page 1 Profile Demographic Data Population Southeast Portland experienced modest population growth (3.1%) compared to the City as a whole (8.7%). -

A Report on the 2003 Parks Levy Investment Objective 1: Restore

A Report on the 2003 Parks Levy Investment In November 2002, Portland voters approved a five-year Parks Levy to begin in July 2003. Levy dollars restored budget cuts made in FY 2002-03 as well as major services and improvements outlined in the Parks 2020 Vision plan adopted by City Council in July 2001. In order to fulfill our obligation to the voters, we identified four key objectives. This report highlights what we have accomplished to date. Objective 1: Restore $2.2 million in cuts made in 2002/03 budget The 2003 Parks Levy restored cuts that were made to balance the FY 2002-03 General Fund budget. These cuts included the closure of some recreational facilities, the discontinuation and reduction of some community partnerships that provide recreational opportunities for youth, and reductions in maintenance of parks and facilities. Below is a detailed list of services restored through levy dollars. A. Restore programming at six community schools. SUN Community Schools support healthy social and cross-cultural development of all participants, teach and model values of respect and inclusion of all people, and help reduce social disparities and inequities. Currently, over 50% of students enrolled in the program are children of color. 2003/04 projects/services 2004/05 projects/services Proposed projects/services 2005/06 Hired and trained full-time Site Coordinators Total attendance at new sites (Summer Continue to develop programming to serve for 6 new PP&R SUN Community Schools: 2004-Spring 2005): 85,159 the needs of each school’s community and Arleta, Beaumont, Centennial, Clarendon, increase participation in these programs. -

Budget Reductions & Urban Forestry Learning Landscapes Plantings

View this email in your browser Share this URBAN FORESTRY January 2016 Get Involved! | Resources | Tree Permits | Tree Problems | Home In This Issue Budget Reductions & Urban Forestry Learning Landscapes Plantings, Urban Forestry in the Schoolyard Hiring Youth Conservation Crew (YCC) Summer Crew Leader, Apply by Thursday, March 3, 2016 Upcoming Urban Forestry Workshops, Free and Open to the Public Budget Reductions & Urban Forestry You may have recently heard about the upcoming 5% budget cuts proposed for Parks programs. Among the difficult reductions proposed, Urban Forestry could be effected by elimination of the $185,000 Dutch Elm Disease (DED) Treatment program. The City of Portland has minimized the spread of DED and avoided the decimation of the American elm (Ulmus americana) with a successful elm monitoring and treatment program. Without advanced warning, rapid detection and removal, the American elm could ultimately vanish from our landscape. Eastmoreland, Ladd’s Addition, the South Park blocks, Lents Park, Laurelhurst Park, and Overlook Park are areas where elms play a significant role in neighborhood identity. "Many communities have been able to maintain a healthy population of mature elms through a vigilant program of identification and removal of diseased elms and systematic pruning of weakened, dying or dead branches" -Linda Haugen, Plant Pathologist, USDA Forest Service Eliminating this program will also require adjacent property owners to cover the cost of removing DED- infected street trees themselves. The cut will also reduce citywide 24/7 emergency response to clear roads of trees which have fallen during storms, and reduce regular maintenance of publicly-owned trees- additional activities performed by some of the same staff . -

PP&R's FY 2021-22 Requested Budget

Requested Budget FY 2021-22 Portland Parks & Recreation PP&R Staff FY 2021-22 Requested Budget Maximo Behrens, Recreation Services Manager Tonya Booker, Land Stewardship Manager Carmen Rubio, Commissioner-in-charge Jenn Cairo, Urban Forestry Manager Tim Collier, Public Information Manager Adena Long, Director Margaret Evans, Workforce Development Manager Todd Lofgren, Deputy Director Vicente Harrison, Security and Emergency Manager Lauren McGuire, Assets and Development Manager Claudio Campuzano, Manager Kenya Williams, Equity and Inclusion Manager Finance, Property, & Technology Department Kerry Anderson Andre Ashley Don Athey Darryl Brooks Budget Advisory Committee Tamara Burkovskaia Krystin Castro Board Members Riley Clark-Long Paul Agrimis Mara Cogswell Mike Elliott Dale Cook Jenny Glass Terri Davis Juan Piantino Leah Espinoza Paddy Tillett Rachel Felice Bonnie Gee Yosick Joan Hallquist Erin Zollenkopf Erik Harrison Britta Herwig Labor Partners Brett Horner Sadie Atwell, Laborers Local 483 Don Joughin Luis Flores, PCL Brian Landoe Yoko Silk, PTE-17 Robin Laughlin Sara Mayhew-Jenkins Community Representatives Todd Melton Pauline Miranda Jeremy Robbins, Portland Accessibility Advisory Council Soo Pak Andre Middleton, Friends of Noise Dylan Paul Chris Rempel, Native American Community Advisory Council Nancy Roth JR Lilly, East Portland Action Plan Victor Sanders Joe McFerrin, Portland Opportunities Industrialization Center Jamie Sandness Brian Flores Garcia, Youth Durelle Singleton Sabrina Wilson, Rosewood Initiative Chris Silkie Jenny -

Streetcar Plan Posters

WELCOME Welcome! The purpose of this open house is to present draft recommendations from the Bicycle Master Plan and the Streetcar System Plan to the public. City sta! and citizen volunteers are here to present the material and to answer questions. The room is divided into three sections: one for the Bicycle Master Plan, one for the Streetcar System Plan, and one called “Integration Station,” where we tie the two concepts together. Refreshments and child care services are also available. The bicycle and streetcar networks will play a key role in Portland’s future. Together, they will reduce reliance on the automobile for daily tasks, they will reinforce urban land use patterns, and they will help the City achieve its goals to combat climate change. This is the beginning of a transportation transformation. WHY PLAN? PORTLAND HAS A HISTORY OF SUCCESSFUL LONG-RANGE PLANNING In 1904, landscape architect John C. Olmsted produced a report for the City Among the parks that resulted from the Olmsted Plan are Holladay Park, Irving Parks Board. The plan served as a blueprint for development of the highly Park, Mt. Tabor (shown above), Overlook Park, Rocky Butte, Sellwood Park, valued park system we enjoy today. Washington Park, and several others. Interstate MAX Opened 2004 Airport MAX Hillsboro MAX Opened 2001 Opened 1998 Portland Streetcar Opened 2001 MAX to Gresham Opened 1986 Clackamas MAX Opens fall 2009 Westside Express Service Opened Feb. 2009 In 1989, three years after the "rst MAX line opened from downtown to Gresham, 20 years later the regional rail system is well on its way to being constructed as planners laid out a vision for a regional rail system. -

2015 DRAFT Park SDC Capital Plan 150412.Xlsx

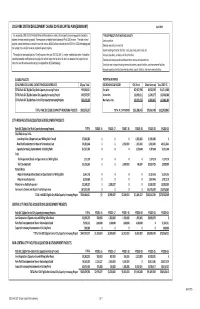

2015 PARK SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT CHARGE 20‐YEAR CAPITAL PLAN (SUMMARY) April 2015 As required by ORS 223.309 Portland Parks and Recreation maintains a list of capacity increasing projects intended to TYPES OF PROJECTS THAT INCREASE CAPACITY: address the need created by growth. These projects are eligible to be funding with Park SDC revenue . The total value of Land acquisition projects summarized below exceeds the potential revenue of $552 million estimated by the 2015 Park SDC Methodology and Develop new parks on new land the funding from non-SDC revenue targeted for growth projects. Expand existing recreation facilities, trails, play areas, picnic areas, etc The project list and capital plan is a "living" document that, per ORS 223.309 (2), maybe modified at anytime. It should be Increase playability, durability and life of facilities noted that potential modifications to the project list will not impact the fee since the fee is not based on the project list, but Develop and improve parks to withstand more intense and extended use rather the level of service established by the adopted Park SDC Methodology. Construct new or expand existing community centers, aquatic facilities, and maintenance facilities Increase capacity of existing community centers, aquatic facilities, and maintenance facilities ELIGIBLE PROJECTS POTENTIAL REVENUE TOTAL PARK SDC ELIGIBLE CAPACITY INCREASING PROJECTS 20‐year Total SDC REVENUE CATEGORY SDC Funds Other Revenue Total 2015‐35 TOTAL Park SDC Eligible City‐Wide Capacity Increasing Projects 566,640,621 City‐Wide -

About East Portland Neighborhoods Vol

EAST PORTLAND NEIGHBORHOOD ASSOCIATION NEWS October 2009 News about East Portland Neighborhoods vol. 14 issue 4 Your NEIGHBORHOOD ASSOCIATIONS Argay pg.pg. pg. pg.5 pg.6 pg. Neighborhood Association 33 4 6 12 Centennial Community Association All about East Portland Glenfair Neighborhood Association Neighborhood Association News … Hazelwood The East Portland in outer East Portland that events, graffiti cleanups, and tribution with positive, far- Neighborhood Association Neighborhood Association make up the EPNO coalition tree plantings. reaching results. News (EPNAN) isn’t a news- (our alliance individual neigh- As you look through our The volunteers of the East Lents paper in the traditional sense. borhoods) – know more paper and see how your Portland Neighbors Inc. Neighborhood Association It wasn’t created to compete about this sanctioned system neighbors are making a real Newspaper Committee thank with community, city or of neighborhood organiza- difference in their neighbor- you for taking a few minutes Mill Park national news outlets – nei- tions, recognized by City gov- hood, perhaps you’ll be to discover more about what Neighborhood Association ther in content nor for adver- ernment. encouraged by their efforts. your neighbors are doing, tisers. So, the stories and photos Then, possibly you’ll decide and how you can help outer Parkrose Heights EPNAN is the way the East you see on the pages inside to take as little as one hour a East Portland be an even Association of Neighbors Portland Neighborhood are about volunteers and month to participate in your nicer place to live when we Organization (EPNO) reach- organizations that are work- neighborhood association work together. -

Fanno Creek Greenway Action Plan Section I

FANNO CREEK GREENWAY TRAIL ACTION PLAN January 2003 Prepared for: Metro Regional Parks and Greenspaces Department Prepared by: Alta Planning + Design METRO COUNCIL FANNO CREEK GREENWAY TRAIL ACTION PLAN WORKING GROUP MEMBERS David Bragdon, President Rex Burkholder Commissioner Dick Schouten, Washington County Carl Hostica Joanne Rice, Washington County Land Use and Transportation Susan McLain Aisha Willits, Washington County Land Use and Transportation Rod Monroe Anna Zirker, Tualatin Hills Park and Recreation District Brian Newman Margaret Middleton, City of Beaverton Transportation Rod Park Roel Lundquist, City of Durham Administrator Duane Roberts, City of Tigard Community Development METRO AUDITOR Justin Patterson, City of Tualatin Parks Jim Sjulin, Portland Parks and Recreation Alexis Dow, CPA Gregg Everhart, Portland Parks and Recreation Courtney Duke, Portland Transportation METRO REGIONAL PARKS AND GREENSPACES DEPARTMENT Don Baack, SWTrails Group of Southwest Neighborhoods, Inc. Bob Bothman, 40-Mile Loop Land Trust Jim Desmond, Director Dave Drescher, Fans of Fanno Creek Heather Kent, Planning and Education Division Manager Sue Abbott, National Park Service Rivers and Trails Program Heather Kent, Metro Planning and Education Division ALTA PLANNING + DESIGN William Eadie, Metro Open Spaces Acquisition Division Bill Barber, Metro Planning George Hudson, Principal Arif Khan, Senior Planner Daniel Lerch, Assistant Planner PROJECT MANAGER Mel Huie, Metro Regional Parks and Greenspaces Department For more information or copies of this report, contact: Mel Huie, Regional Trails Coordinator (503) 797-1731, [email protected] Metro Regional Services Alta Planning + Design 600 NE Grand Ave. 144 NE 28th Ave. Portland, OR 97232 Portland, OR 97232 (503) 797-1700 (503) 230-9862 www.metro-region.org www.altaplanning.com FANNO CREEK GREENWAY TRAIL ACTION PLAN Contents I. -

ORDINANCE NO. 187150 As Amended

ORDINANCE NO. 187150 As Amended Accept Park System Development Charge Methodology Update Report for implementation, and amend the applicable sections of City Code (Ordinance; amend Code Chapter 17.13) The City of Portland ordains: Section 1. The Council finds: 1. Ordinance No. 172614, passed by the Council on August 19, 1998 authorized establishment of a Parks and Recreation System Development Charge(SDC) and created a new City Code Chapter 17.13. 2. In October 1998 the City established a Parks SDC program. City Code required that the program be updated every two years to ensure that program goals were being met. An update was implemented on July 1, 2005 pursuant to Ordinance No. 179008, as amended. The required update reviewed the Parks SDC Program to determine that sufficient money will be available to fund capacity-increasing facilities identified by the Parks SDC-CIP; to determine whether the adopted and indexed SDC rate has kept pace with inflation; to determine whether the Parks SDC-CIP should be modified; and to ensure that SDC receipts will not over-fund such facilities. 3. Ordinance No 175774, passed by the Council on July 12, 2001 adopted The Parks 2020 Vision. This report highlighted significant challenges confronting the City in regards to shoring up our ailing park facilities, eliminating inequity in underserved neighborhoods, and providing a stable source of funding to address not just our existing shortfalls, but to also meet the needs created by new development. The Park SDC is the most significant revenue opportunity available to Parks to address growth. It is imperative that this opportunity is maximized to recover reasonable costs from new development. -

National Register of Historic Places J Registration Form I -S

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) r———— ————————, , ' "• ^ o-->~^ i United States Department of the Interior ^ i National Park Service i 9 : j National Register of Historic Places j Registration Form i_——— ~————--... — ..„ . „ • , -. ';; -,....T_- _si_il | This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property______________________________________________________ historic name Laurelhurst Park other names/site number Ladd Park 2. Location street & number 3554 SE Ankeny Street_______________ rj not for publication city or town Portland________________________ Q vicinity state Oregon________ code OR county Multnomah_______ code 051 zip code 97204 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Addresses an Existing Deficiency Or Hazard by Improving Pedestrian, Bicycle, And/Or Vehicular Safety

Attachment 1. Public comment report www.oregonmetro.gov Public comment report for the June 2014 www.oregonmetro.gov/rtp 2014 Metro respects civil rights Metro fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes that ban discrimination. If any person believes they have been discriminated against regarding the receipt of benefits or services because of race, color, national origin, sex, age or disability, they have the right to file a complaint with Metro. For information on Metro’s civil rights program, or to obtain a discrimination complaint form, visit www.oregonmetro.gov/civilrights or call 503-797-1536. Metro provides services or accommodations upon request to persons with disabilities and people who need an interpreter at public meetings. If you need a sign language interpreter, communication aid or language assistance, call 503-797-1700 or TDD/TTY 503-797-1804 (8 a.m. to 5 p.m. weekdays) 5 business days before the meeting. All Metro meetings are wheelchair accessible. For up-to-date public transportation information, visit TriMet’s website at www.trimet.org. Metro is the federally mandated metropolitan planning organization designated by the governor to develop an overall transportation plan and to allocate federal funds for the region. The Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation (JPACT) is a 17-member committee that provides a forum for elected officials and representatives of agencies involved in transportation to evaluate transportation needs in the region and to make recommendations to the Metro Council. The established decision-making process assures a well-balanced regional transportation system and involves local elected officials directly in decisions that help the Metro Council develop regional transportation policies, including allocating transportation funds.