This Document Is with a Copy of the Following Article Published by the Mining Heritage Trust of Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Borrisokane ,Co.Tipperary

History of Borrisokane ,Co.Tipperary. ‘Introduction’ What better way to begin an account of a Tipperary town than by referring to the following words of a poem called ‘Tipperary‘.In these lines, the poet ‘ Eva of the Nation‘ who was one of the Kellys of Killeen, Portumna,wrote: ‘O come for a while among us,and give us a friendly hand, And you‘ll see that old Tipperary is a loving and gladsome land; From Upper to Lower Ormond bright welcome and smiles will spring, On the plains of Tipperary,the stranger is like a king?‘ Yes, I think the words ring true,I`m sure, for us and about us,natives of this part of Irish soil?? It is about one particular spot ‘on the plains of Tipperary‘ that I wish to write, namely my home parish of Borrisokane?? . So I turn again to verse, which so often suggests things that mere prose cannot? In a book of poetry, ‘The Spirit of Tipperary‘ published many years ago by the Nenagh Guardian,we find a poem by Dermot F ?Gleeson who for many years was District Justice in Nenagh.He wrote under the pen-name ‘Mac Liag‘ . He writes as if from the top of Lisgorrif Hill looking down on the broad expanse of the two Ormonds with Lough Derg bordering them to the left? .The poem is simply called, ‘The place where I was born’ ‘O’er hill and mountain, vale and town, My gaze now wanders up and down, Anon my heart is filled with pride, Anon with memory’s gentler tide ‘ Of sorrow, until through them all The twilight whispers softly call From upland green and golden corn “It is the place where you were born”. -

Cashel-Tipperary District

CASHEL-TIPPERARY DISTRICT Welcome Located in the western part of County Tipperary, the District has two towns within its region – Tipperary and Cashel. West Tipperary is a central location to operate business from with key arterial routes linking all major cities and airports. Cashel, located in the heart of County Tipperary, is home to the internationally renowned Rock of Cashel – one of the top visitor attractions in Ireland. Cashel has been included in the tentative list of sites for UNESCO World Heritage status. Once the home of the high kings of Munster, 21st century Cashel combines a passion and respect for its proud heritage with the amenities and experience of a modern Irish town that is within easy reach of all the larger centres of population in Ireland. Tipperary is a heritage town with a long tradition in trading particularly in relation to its rich agricultural hinterland. The wonderful scenic Glen of Aherlow within 15 minutes drive of the town is nestled within the folds of the Galtee mountains offering miles of walking and activity trails for the outdoor enthusiast or for a quiet walk after work. www.tipperary.ie Photo by D. Scully D. Photo by CASHEL-TIPPERARY DISTRICT Links to cities (time) Dublin (130 mins), Limerick (70 mins), Cork (70 mins), Galway (140 mins), Waterford (75 mins), Belfast (220 mins) Roscrea Motorways M8 Dublin–Cork route from Cashel (5 mins) Nenagh Airports Dublin (125 mins), Shannon (75 mins), Cork (75 mins), Waterford (75 mins) Thurles Sea Ports Cashel-Tipperary Rosslare (125 mins), Cork (70 mins), -

Information Guide to Services for Older People in County Tipperary

Information Guide to Services for Older People in County Tipperary NOTES ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Notes ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Tipperary – It’S a Great Place to Live

Welcome to Tipperary – It’s a great place to live. www.tipperary.ie ü Beautiful unspoilt area with the Glen of Aherlow, mountains and rivers nearby. ü Superb Medical Facilities with hospitals and nursing homes locally. ü Major IR£3.5 million Excel Cultural and Entertainment Centre just opened with Cinemas, Theatre, Art gallery and café. ü Quick Access to Dublin via Limerick Junction Station - just 1hour 40 minutes with Cork and Shannon Airport just over 1 Hour. ü Wealth of sporting facilities throughout to cater for everyone. ü Tremendous Educational Facilities available. Third level nearby. ü Proven Community Spirit with positive attitude to do things themselves’. ü A Heritage Town with a great quality of life and a happy place to live. ü A cheaper place to live - better value for money – new homes now on the market for approx €140k. Where is Tipperary Town? Tipperary Town is one of the main towns in County Tipperary. It is situated on the National Primary Route N24, linking Limerick and Waterford road, and on the National Secondary Route serving Cashel and Dublin, in the heart of the ‘Golden Vale’ in the western half of south Tipperary. It is approximately twenty-five miles from both Clonmel and Limerick. Tipperary town lies in the superb scenic surroundings at the heart of the fertile ‘Golden Vale’. Four miles from the town’s the beautiful secluded Glen of Aherlow between the Galtee Mountains and the Slievenamuck Hills with magnificent panoramic views and ideal for hill walking and pony-trekking. Tipperary is a Heritage town designated as such by Bord Failte Located on the main rail rout from Waterford to Limerick, and in close proximity to Limerick Junction, the town is served with an Express Rail Service on the Cork-Dublin line with a connection to Limerick and www.tipperary.ie 1 Waterford. -

Obituaries and Funeral Reports in the Limerick Chronicle Newspaper

Obituaries and Funeral Reports in the Limerick Chronicle newspaper, 1880-1922 Surname Forename Address Date Notes Abel George 30/12/1916 lesee and manager of the Theatre Royal; obituary (funeral report, 02/01/1917) Adamson John Janesborough, Southill 29/01/1895 accidental drowning at the docks Adderley Joseph Corcomohide, Co. Limerick 16/03/1915 rector of Corcomohide; obituary Aherin E. Lloyd Hernsbrook, Newcastle West 01/03/1913 doctor; obituary (funeral report, 08/03/1913) Alexander James 11/05/1915 accidental drowning; obituary Allan Adeline Annie Aberdeen 09/07/1898 granddaughter of late Henry Purdon Wilkinson, George Street Allbutt Annie (née Liverpool 18/11/1893 daughter of Col. Blood-Smythe, Blood-Smythe) Fedamore Allen James Hastings, Very Clonlara 11/05/1880 Dean of Killaloe (short death Rev. notice, 11/5/1880) Allen Richard 26/01/1886 extract from will Alley Mary D. "Olivette", Ennis Road 08/06/1915 daughter of Gabriel Alley; short death notice Alton James Poe 4 Herbert Street, Dublin 08/04/1922 banker; son of John Bindon Alton of Corbally Ambrose James New Road, Thomondgate 04/07/1922 accidental drowning Ambrose James Killeedy 17/10/1922 civil war casualty Ambrose John Pigott Arms Hotel, Rathkeale 25/02/1913 hotelier Angley Malcolm H. Albert Cottage 06/09/1904 son of William Ponsonby Angley Annesley John R. 14/01/1893 house steward of the Limerick County Club Apjohn Frances Sunville 01/01/1880 daughter of Thomas Apjohn, short death notice Apjohn James, Professor Blackrock, Dublin 01/06/1886 from Sunville, Grean, Co. Limerick Apjohn Marshal Lloyd Linfield House, Newpallas 12/03/1895 Armstrong Andrew, Rev. -

BMH.WS0881.Pdf

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 881 Witness James Kilmartin, Cutteen, Monard, Co. Tipperary. Identify. Member of Irish Volunteers, Solohead, Co. Tipperary, 1917 - ; Second in Command, No. 1 Flying Column 3rd Tipperary Brigade. Subject. Irish Volunteers, Co. Tipperary, 1917-1921. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No S.2155 Form BSM2 Statement of James Kilmartin, Cutteen, Monard, Co. Tipperary. CONTENTS. Page - 1. Personal background first meeting with Seán Treacy and introduction to national movement. - 2. Appointment as Company Captain Solohead Company. 1 2. Attacks on R.I.C. Barracks and other activities of the Solohead Company. 2 - 5. 3. The formation of the No. 1 Column of the 3rd Tipperary Brigade. The Oola ambush following General Lucas's escape 30/7/1920. 6 - 8. 4. Thomastown ambush, Glen of Aherlow ambush. Enemy burnings in Tipperary in reprisal. 8 - 9. 5. Disbandment of the Column for Christmas leave. A fight at Solohead during the reassembly and the burning of houses at Solohead in reprisal. 9 - 10. 6. Attacks on Dundrum, Annacarthy and Limerick Junction R.I.C. Barracks January, 1921. 10. 7. Reference to other attacks carried out on Barracks at Holycross, Glenbower, Roskeen and Lisaronan. 11. 8. Attack on a B. & T. patrol in Mullinahone, Co. Kilkenny. 11. 9. Accidental shooting of Dinny Sadlier. 11 - 12. 10. March 1921: Digging dumps in the Comeragh Mountains for the arms to be landed in Waterford. 12. 11. Ambush at Garrymore crossroads between Clogheen and Cahir after which D.I. Potter was captured. -

Griffiths Valuation of Ireland

Dwyer_Limerick Griffiths Valuation of Ireland Surname First Name Townland Parish County Dwyer Patrick Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer William Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Ellen Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer William Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Ellen Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Ellen Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer William Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cloghnadromin Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cloghnadromin Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cloghnadromin Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Coolbreedeen Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Coolbreedeen Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Coolbreedeen Abington Limerick Dwyer John Gleno Abington Limerick Dwyer John Gleno Abington Limerick Dwyer John Gleno Abington Limerick Dwyer James Gleno Knocklatteragh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Gleno Knocklatteragh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Gleno Knocklatteragh Abington Limerick Dwyer Catherine Gortavacoosh -

CHAPTER 3 POPULATION and SETTLEMENT Population and Settlement

CHAPTER 3 POPULATION AND SETTLEMENT Population and Settlement 3. POPULATION AND SETTLEMENT Main Sections in this Chapter include: 1. North Tipperary in Context 2. Housing Strategy 3. Current and Projected Population 4. County Settlement Pattern 5. County Settlement Strategy 6. Preferred Settlement Strategy 7. Existing Development Plans and Local Area Plans 8. Social Inclusion 3.1 North Tipperary in Context rivers such as the Nenagh, Ollatrim and Ballintotty Rivers. The size of County Tipperary led to it being split into two ‘Ridings’ in 1838. The county is largely underlain by While many of the inhabitants of limestone with the higher terrain of the Tipperary do not readily differentiate County composed of geological deposits between North and South Tipperary, as it dating from Silurian and Devonian is culturally identified as one county, they periods. Over the centuries the valleys are two separate counties for the purpose and hills formed into rich peatlands, which of local government. All references to occupy approximately 28,333 hectares ‘County’ in this Plan will, therefore, be to (70,000 acres) or 13% of the total area of North Tipperary. the County. North Tipperary is an inland county in the The Motorways and National Primary mid-west/midlands of Ireland and covers Roads: M8 (Dublin to Cork) and N7/M7 an area of 202,430 ha or 500,000 acres (in (Dublin to Limerick) traverse the County, extent). It is also situated in the Mid West as do the National Secondary Routes the Region of the County for the Regional N62 (Roscrea to Thurles), the N65 Planning Guidelines and Economic (Borrisokane to Portumna), the N75 Strategy and the Midlands Region for the (Thurles to Turnpike) and the N52 (Birr to Waste Management Plan. -

Localenterpriseweekevents Flyer

Tipperary #localenterprise www.localenterprise.ie The first nationally co-ordinated ‘Local Enterprise Week’ takes place around the country from March 7th to 13th 2016. Organised by the Local Enterprise Offices, these events are aimed at anyone thinking of starting a business, Wednesday 09 March Thursday 10 March new start-ups and growing SMEs. 8am-10am Owner/Manager Breakfast Horse & Jockey Hotel, Thurles 7pm-9pm Social Enterprise Work Shop Tipperary Community Centre, Tipperary Town Owning and managing a small business can be a lonely job. In the course of any one day, you may have to act as an This event will offer information and advice to those interested in establishing a Social Enterprise. Learn about the key accountant; a marketing person, a sales person, a HR manager, a buyer etc. None of us have inherited the full range of steps involved, the likely challenges and how to overcome them. Avail of the opportunity to hear from those who have Monday 07 March management skills, therefore we must acquire a working knowledge of them, if we are to be commercially successful successfully established a Social Enterprise and gain an insight into what is required to initiate and develop a project. going forward. Come to this Breakfast Event to meet with Blaise Brosnan MRI Wexford and hear details of of our Booking Essential Free to attend Management Development Programme which is aimed at the owner managers of small businesses, who are anxious to 10am-1pm The Anner Hotel, Thurles Who to Talk To Expo acquire the extra skills/ knowledge to develop their businesses on to the next stage. -

The Growth and Development of Sport in Co. Tipperary, 1840 to 1880, Was Promoted and Supported by the Landed Elite and Military Officer Classes

THE GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF SPORT IN CO. TIPPERARY, 1840 – 1880 PATRICK BRACKEN B.A., M.Sc. Econ. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR SPORTS HISTORY AND CULTURE AND THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORICAL AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES DE MONTFORT UNIVERSITY LEICESTER SUPERVISORS OF RESEARCH: FIRST SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR TONY COLLINS SECOND SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR MIKE CRONIN NOVEMBER 2014 Table of Contents List of figures ii List of tables iv Abbreviations v Acknowledgments vi Abstract vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1. Sport and the Military 31 Chapter 2. Country House Sport 64 Chapter 3. The Hunt Community 117 Chapter 4. The Turf : Horse Racing Development and Commercialisation 163 Chapter 5. The Advent of Organised Athletics and Rowing 216 Chapter 6. Ball Games 258 Chapter 7. Conclusion 302 Bibliography 313 i List of Figures Figure 1: Location of Co. Tipperary 10 Figure 2: Starvation deaths in Ireland, 1845-1851 11 Figure 3: Distribution of army barracks in Ireland, 1837 13 Figure 4: Country houses in Co. Tipperary with a minimum valuation of £10, c.1850 66 Figure 5: Dwelling houses of the dispersed rural population valued at under £1, c.1850 66 Figure 6: Archery clubs in Co. Tipperary, 1858-1868 83 Figure 7: Archery meeting at Marlfield House, date unknown 86 Figure 8: Map of Lough Derg, 1842 106 Figure 9: Location of Belle Isle on the shores of Lough Derg, 1842 107 Figure 10: Watercolour of The Fairy on Lough Derg, 1871 109 Figure 11: Distribution of the main hunt packs in Co. Tipperary, 1840-1880 121 Figure 12: Number of hunt meets in Co. -

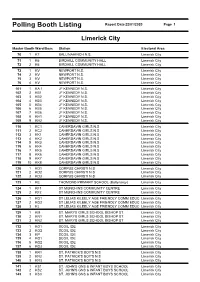

Polling Booth Listing Report Date 22/01/2020 Page 1

Polling Booth Listing Report Date 22/01/2020 Page 1 Limerick City Master Booth Ward/Desc Station Electoral Area 70 1 K7 BALLINAHINCH N.S. Limerick City 71 1 K6 BIRDHILL COMMUNITY HALL Limerick City 72 2 K6 BIRDHILL COMMUNITY HALL Limerick City 73 1 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 74 2 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 75 3 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 76 4 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 101 1 KA.1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 102 2 KB1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 103 3 KB2 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 104 4 KB3 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 105 5 KB4 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 106 6 KB5 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 107 7 KB6 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 108 8 KH1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 109 9 KH2 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 110 1 KC1 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 111 2 KC2 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 112 3 KK1 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 113 4 KK2 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 114 5 KK3 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 115 6 KK4 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 116 7 KK5 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 117 8 KK6 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 118 9 KK7 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 119 10 KK8 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 120 1 KD1 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 121 2 KD2 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 122 3 KD3 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 123 1 KE THOMOND PRIMARY SCHOOL (Ballynanty) Limerick City 124 1 KF1 ST MUNCHINS COMMUNITY CENTRE Limerick City 125 2 KF2 ST MUNCHINS COMMUNITY CENTRE Limerick City 126 1 KG1 ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 127 2 KG2 ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 128 3 KJ ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 129 1 KM ST. -

Economic Plan 2015 – 2020

CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND 4 2. METHODOLOGY 4 2.1 LECP PROCESS 5 3.1.1 Phase 1 5 3.1.2 Phase 2 5 3.1.3 Phase 3 5 3.2 SEA SCREENING & EQUALITY PROOFING EXERCISES 5 3.3 LECP PRIORITY CONSTRAINTS 6 3.4 KEY ECONOMIC ISSUES 6 4. KEY POLICIES – EU, NATIONAL & REGIONAL POLICIES 7 4.1 EU AND NATIONAL POLICIES 7 4.1.1 Europe 2020 7 4.1.2 Horizon 2020 7 4.1.3 Research on SMEs & Microenterprise in Europe 8 4.1.4 Action Plan for Jobs 8 4.1.5 Entrepreneurship in Ireland Policy Statement 2014 9 4.1.6 Climate Change & Energy Sustainability Policy 9 4.1.7 Solas Further Education & Training Strategy 10 4.1.8 National Broadband Plan 10 4.1.9 Food Wise 2025 11 4.1.10 People, Place and Policy – Growing Tourism to 2025 12 4.1.11 CEDRA Report 12 4.1.12 Rural Development Programme 2014 -2020 Ireland 12 4.2. REGIONAL & LOCAL ECONOMIC POLICIES 13 4.3 SUMMARY 14 5. SUPPORT AGENCIES & ORGANISATIONS 16 5.1 IDA IRELAND (I NDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY ) 16 5.2 ENTERPRISE IRELAND (EI) 16 5.3 LOCAL ENTERPRISE OFFICE (LEO), TIPPERARY 16 5.4 TEAGASC 16 5.5 TOURISM IRELAND (TI) 16 5.6 FÁILTE IRELAND (FI) 16 5.7 TIPPERARY EDUCATION &T RAINING BOARD (ETB) 17 5.8 LOCAL DEVELOPMENT COMPANIES (LDC) 17 5.9 TIPPERARY ENERGY AGENCY (TEA) 17 5.10 UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK (UL) 17 5.11 LIT, LIMERICK & TIPPERARY 17 5.12 WATERFORD INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY (WIT) 17 5.13 ST.