BMH.WS0881.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tipperary News Part 6

Clonmel Advertiser. 20-4-1822 We regret having to mention a cruel and barbarous murder, attended with circumstances of great audacity, that has taken place on the borders of Tipperary and Kilkenny. A farmer of the name of Morris, at Killemry, near Nine-Mile-House, having become obnoxious to the public disturbers, received a threatening notice some short time back, he having lately come to reside there. On Wednesday night last a cow of his was driven into the bog, where she perished; on Thursday morning he sent two servants, a male and female, to the bog, the male servant to skin the cow and the female to assist him; but while the woman went for a pail of water, three ruffians came, and each of them discharged their arms at him, and lodged several balls and slugs in his body, and then went off. This occurred about midday. No one dared to interfere, either for the prevention of this crime, or to follow in pursuit of the murderers. The sufferer was quite a youth, and had committed no offence, even against the banditti, but that of doing his master’s business. Clonmel Advertiser 24-8-1835 Last Saturday, being the fair day at Carrick-on-Suir, and also a holiday in the Roman Catholic Church, an immense assemblage of the peasantry poured into the town at an early hour from all directions of the surrounding country. The show of cattle was was by no means inferior-but the only disposable commodity , for which a brisk demand appeared evidently conspicuous, was for Feehans brown stout. -

Moycarkey Old Graveyard Headstone Inscriptions

Moycarkey Old Graveyard Headstone Inscriptions Three Monuments inside the Catholic church. 1 Beneath lie the remains / Of / Revd. John Burke /(native of Borris) / He was born 1809 Ordained priest 1839 / Appointed P P Moycarkey & Borris 1853 /Died 2nd August 1891 /R.I.P. / Erected by the people of Moycarkey. Stonecutter P.J. O'Neill & Co. Gr. Brunswick St, Dublin. 2 Beneath are deposited / The remains of the / Rev Patrick O'Grady /Of Graigue Moycarkey / Died on the English mission / At London /On the 17th of Jan 1887 / Aged 26 years / Erected by his loving father. Stonecutter. Bracken Templemore 3 Beneath / Are deposited the remains of /The Rev Robert Grace P.P. of /Moycarkey and Borris / Who departed this life the 2nd / Of Octr. 1852 / Aged 60 years /Requiescat in pace / Erected by Revd. Richd. Rafter. Stonecutter. J. Farrell Glasnevin. 1 Headstones on Catholic church grounds. 1 Erected by / William Max Esq / Of Maxfort / In memory of / His dearly beloved wife / Margaret / Who died 2nd Novr 1865 / Most excellent in every relation of life / A most devoted wife / And sterling friend / Also the above named / William Max Esq /Died 1st Feby 1867 aged 72 years / Deeply regretted by / A large circle of friends / R.I.P. 2 Very Rev Richard Ryan / Parish Priest / of / Moycarkey, Littleton and Two-Mile-Borris / 1986-2002 / Died 10th January 2002 / Also served God and God’s people / In / Raheny, Doon, Ballylanders / Thurles and Mullinahone / Requiescat in pace. 3 In memory of / Very Rev. Daniel M. Ryan / Born Ayle, Cappawhite November 26th 1915 / Ordained priest Maynooth June 22 1941 / Professor St Patricks College Carlow 1942 – 1947 / Professor St Patricks College Thurles 1947 – 1972 / Parish priest Moycarkey Borris 1972 – 1986 / Associate pastor Lisvernane December 1986 / Died feast of St Bridget February 1st 1987 / A Mhuire na nGael gui orainn. -

Rev Walter Skehan, Notes Vol 43 with QUIRKE Partial

Title: Rev. Walter Skehan, Notes, Vol 43 –(partial) Ireland Genealogy Projects Archives Tipperary Index Copyright Contributed by: Mary Quirk-Thompson __________________________________ Rev. Walter Skehan Notes. Vol 43 pg 69 Pat Quirke married Ellen Stokes pg 112 same Pat Quirke married Catherine Fitzgerald Blue when Quirke listed Or go to http://fanningfamilyhistory.com/index.php/2014/08/27/walter-skehan- papers-vol-43/ “Rev Walter Skehan Papers Vol 43 The papers of Rev Father Walter G Skehan 1905- 1971 contain much genealogical information about various Irish families. He was parish priest of Loughmore and Castleiny Co Tipperary 1960 – 1971 and a keen family historian. He is buried in Loughmore Cemetery.”Kathleen Fanning C. 1786, Walter Skehan (a), of Coolbawn married firstly Mary O’Dea (w-a). Issue:- 3 Children:- (1). John (aa), born 1787 = Mary Ryan? 1824. Said to have been implicated in a faction fight in which a man was murdered: given Coolbawn to his step-brother, Darby, and fled to U.S.A. He is believed to have been married and that his eldest child was named Walter. John Skehan (aa) was baptised on 3rd May 1787. But it must be noted that there is a John Skehan who died 18th May, 1804, aged 77, and is buried at St. Johnstown with other members of the family: but he however would be too old to be same person as above John, and is perhaps the father of Walter (a). John Skehan (aa) was married in Coolbawn and had family who went to America with him. ?Married C. 1824-5 Mary Ryan…. -

The Tipperary

Walk The Tipperary 10 http://alinkto.me/mjk www.discoverireland.ie/thetipperary10 48 hours in Tipperary This is the Ireland you have been looking for – base yourself in any village or town in County Tipperary, relax with friends (and the locals) and take in all of Tipperary’s natural beauty. Make the iconic Rock of Cashel your first stop, then choose between castles and forest trails, moun- tain rambles or a pub lunch alongside lazy rivers. For ideas and Special Offers visit www.discoverireland.ie/thetipperary10 Walk The Tipperary 10 Challenge We challenge you to walk all of The Tipperary 10 (you can take as long as you like)! Guided Walks Every one of The Tipperary 10 will host an event with a guide and an invitation to join us for refreshments afterwards. Visit us on-line to find out these dates for your diary. For details contact John at 087 0556465. Accommodation Choose from B&Bs, Guest Houses, Hotels, Self-Catering, Youth Hostels & Camp Sites. No matter what kind of accommodation you’re after, we have just the place for you to stay while you explore our beautiful county. Visit us on line to choose and book your favourite location. Golden to the Rock of Cashel Rock of Cashel 1 Photo: Rock of Cashel by Brendan Fennssey Walk Information 1 Golden to the Rock of Cashel Distance of walk: 10km Walk Type: Linear walk Time: 2 - 2.5 hours Level of walk: Easy Start: At the Bridge in Golden Trail End (Grid: S 075 409 OS map no. 66) Cashel Finish: At the Rock of Cashel (Grid: S 012 384 OS map no. -

Co Tipperary Burial Ground Caretakers

BURIAL GROUND CARETAKER ADDRESS1 Address2 Address3 PHONE NO Aglish Elizabeth Raleigh Aglish Roscrea Co. Tipperary 067 21227 Aglish Thomas Breen Graigueahesia Urlingford Co. Tipperary 056‐8834346 062‐75525 087‐ Annacarthy Pat English Rossacrowe Annacarthy Co. Tipperary 6402221 Annameadle Thomas O'Rourke Annameadle Toomevara Nenagh 067‐26122 Ardcroney‐New Paddy Horrigan Crowle Cloughjordan 087‐ 6744676 Ardcroney‐Old Paddy Horrigan Crowle Cloughjordan Nenagh 087‐6744676 Ardfinnan Alfie & Anne Browne The Boreen Ardfinnan Clonmel 052‐7466487 062‐72456 087‐ Athassel Thomas Boles 6 Ard Mhuire Golden Co. Tipperary 2923148 Ballinacourty Jerome O' Brien 2 Annville Close Lisvernane Co. Tipperary 087‐3511177 Ballinahinch Thomas McLoughlin Grawn Ballinahinch 061‐379186 Ballinaraha James Geoghegan Ballinaraha Kilsheelan Clonmel 087‐6812191 Ballingarry Old Michael Perdue Old Church Road Ballingarry Co. Tipperary 089‐4751863 Ballybacon Alfie & Anne Browne The Boreen Ardfinnan Clonmel 052‐7466487 Ballinree Pat Haverty Lissanisky Toomevara Nenagh 086‐ 3462058 Ballinure Johanna Hayde Creamery Road Ballinure Thurles 052‐9156143 062‐71019 087‐ Ballintemple Kieran Slattery Deerpark Dundrum Co. Tipperary 7934071 Ballycahill Patrick Cullagh Garrynamona Ballycahill Thurles 0504‐21679 Ballyclerihan Old & 052‐6127754 083‐ New Michael Looby Kilmore Clonmel Co. Tipperary 4269800 Ballygibbon Ann Keogh Ballygibbon Nenagh 087 6658602 Ballymackey Pat Haverty Lissanisky Toomevara Nenagh 086‐ 3462058 Ballymoreen No Caretaker 0761 06 5000 Barnane Vacant at present 0761 06 -

Information Guide to Services for Older People in County Tipperary

Information Guide to Services for Older People in County Tipperary NOTES ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Notes ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Tipperary – It’S a Great Place to Live

Welcome to Tipperary – It’s a great place to live. www.tipperary.ie ü Beautiful unspoilt area with the Glen of Aherlow, mountains and rivers nearby. ü Superb Medical Facilities with hospitals and nursing homes locally. ü Major IR£3.5 million Excel Cultural and Entertainment Centre just opened with Cinemas, Theatre, Art gallery and café. ü Quick Access to Dublin via Limerick Junction Station - just 1hour 40 minutes with Cork and Shannon Airport just over 1 Hour. ü Wealth of sporting facilities throughout to cater for everyone. ü Tremendous Educational Facilities available. Third level nearby. ü Proven Community Spirit with positive attitude to do things themselves’. ü A Heritage Town with a great quality of life and a happy place to live. ü A cheaper place to live - better value for money – new homes now on the market for approx €140k. Where is Tipperary Town? Tipperary Town is one of the main towns in County Tipperary. It is situated on the National Primary Route N24, linking Limerick and Waterford road, and on the National Secondary Route serving Cashel and Dublin, in the heart of the ‘Golden Vale’ in the western half of south Tipperary. It is approximately twenty-five miles from both Clonmel and Limerick. Tipperary town lies in the superb scenic surroundings at the heart of the fertile ‘Golden Vale’. Four miles from the town’s the beautiful secluded Glen of Aherlow between the Galtee Mountains and the Slievenamuck Hills with magnificent panoramic views and ideal for hill walking and pony-trekking. Tipperary is a Heritage town designated as such by Bord Failte Located on the main rail rout from Waterford to Limerick, and in close proximity to Limerick Junction, the town is served with an Express Rail Service on the Cork-Dublin line with a connection to Limerick and www.tipperary.ie 1 Waterford. -

Obituaries and Funeral Reports in the Limerick Chronicle Newspaper

Obituaries and Funeral Reports in the Limerick Chronicle newspaper, 1880-1922 Surname Forename Address Date Notes Abel George 30/12/1916 lesee and manager of the Theatre Royal; obituary (funeral report, 02/01/1917) Adamson John Janesborough, Southill 29/01/1895 accidental drowning at the docks Adderley Joseph Corcomohide, Co. Limerick 16/03/1915 rector of Corcomohide; obituary Aherin E. Lloyd Hernsbrook, Newcastle West 01/03/1913 doctor; obituary (funeral report, 08/03/1913) Alexander James 11/05/1915 accidental drowning; obituary Allan Adeline Annie Aberdeen 09/07/1898 granddaughter of late Henry Purdon Wilkinson, George Street Allbutt Annie (née Liverpool 18/11/1893 daughter of Col. Blood-Smythe, Blood-Smythe) Fedamore Allen James Hastings, Very Clonlara 11/05/1880 Dean of Killaloe (short death Rev. notice, 11/5/1880) Allen Richard 26/01/1886 extract from will Alley Mary D. "Olivette", Ennis Road 08/06/1915 daughter of Gabriel Alley; short death notice Alton James Poe 4 Herbert Street, Dublin 08/04/1922 banker; son of John Bindon Alton of Corbally Ambrose James New Road, Thomondgate 04/07/1922 accidental drowning Ambrose James Killeedy 17/10/1922 civil war casualty Ambrose John Pigott Arms Hotel, Rathkeale 25/02/1913 hotelier Angley Malcolm H. Albert Cottage 06/09/1904 son of William Ponsonby Angley Annesley John R. 14/01/1893 house steward of the Limerick County Club Apjohn Frances Sunville 01/01/1880 daughter of Thomas Apjohn, short death notice Apjohn James, Professor Blackrock, Dublin 01/06/1886 from Sunville, Grean, Co. Limerick Apjohn Marshal Lloyd Linfield House, Newpallas 12/03/1895 Armstrong Andrew, Rev. -

Griffiths Valuation of Ireland

Dwyer_Limerick Griffiths Valuation of Ireland Surname First Name Townland Parish County Dwyer Patrick Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer William Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Ellen Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer William Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Ellen Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Ellen Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer William Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cloghnadromin Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cloghnadromin Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cloghnadromin Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Coolbreedeen Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Coolbreedeen Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Coolbreedeen Abington Limerick Dwyer John Gleno Abington Limerick Dwyer John Gleno Abington Limerick Dwyer John Gleno Abington Limerick Dwyer James Gleno Knocklatteragh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Gleno Knocklatteragh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Gleno Knocklatteragh Abington Limerick Dwyer Catherine Gortavacoosh -

Roinn Cosanta. Bureau of Military History, 1913-21

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. NO. 1647. DOCUMENT W.S. Witness John J. O'Brien, 29, Emmet Road, Inchicore, Dublin. Identity. Member of "Knocklong Rescue" Party. Vice Comdt., 6th Battn., East Limerick Bde. Subject. Irish Co. Galbally Coy., Volunteers, Limerick, and No. 3 Flying Tipperary Brigade, Column, 1913-21. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil. File No S.2970. Form B.S.M.2 STATEMENT OF MR. JOHN J. O'BRIEN, 29 Emmet Road, Inchicore, Dublin. I was born at Mitchelstown, Co. Cork, in the year 1897, being the youngest of three brothers in our family. In the same year, my father, William O'Brien, who had a drapery premises in Mitchelstown, transferred his business to Galbally Co. Limerick, where the family went to reside. I was educated in Galbally and, at the end of 1912, I went back to Mitchelstown as an apprentice to the drapery business in the firm of Denis Forrest, Lower Cork St., and, later, as an assistant in O'Keeffe Brothers. When an Irish Volunteer Company was formed in Mitchelstown, early in December 1913, I immediately joined. I think the first company captain was James O'Neill of Mitchelstown. We did a lot of training which included route marches on which we were generally accompanied by two bands a pipe and a brass. Shortly after the Great war started in l914, some of the company officers including, I think, James O'Neill, went to Birmingham, England, and there purchased about 40 Lee Enfield rifles and 100 rounds of ammunition per rifle for the company, They got the rifles and ammunition safely to Mitchelstown. -

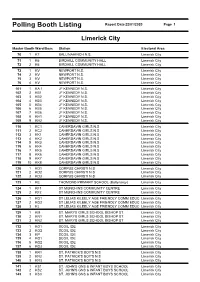

Polling Booth Listing Report Date 22/01/2020 Page 1

Polling Booth Listing Report Date 22/01/2020 Page 1 Limerick City Master Booth Ward/Desc Station Electoral Area 70 1 K7 BALLINAHINCH N.S. Limerick City 71 1 K6 BIRDHILL COMMUNITY HALL Limerick City 72 2 K6 BIRDHILL COMMUNITY HALL Limerick City 73 1 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 74 2 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 75 3 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 76 4 KV NEWPORT N.S. Limerick City 101 1 KA.1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 102 2 KB1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 103 3 KB2 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 104 4 KB3 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 105 5 KB4 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 106 6 KB5 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 107 7 KB6 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 108 8 KH1 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 109 9 KH2 JF KENNEDY N.S. Limerick City 110 1 KC1 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 111 2 KC2 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 112 3 KK1 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 113 4 KK2 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 114 5 KK3 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 115 6 KK4 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 116 7 KK5 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 117 8 KK6 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 118 9 KK7 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 119 10 KK8 CAHERDAVIN GIRLS N.S Limerick City 120 1 KD1 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 121 2 KD2 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 122 3 KD3 CORPUS CHRISTI N.S Limerick City 123 1 KE THOMOND PRIMARY SCHOOL (Ballynanty) Limerick City 124 1 KF1 ST MUNCHINS COMMUNITY CENTRE Limerick City 125 2 KF2 ST MUNCHINS COMMUNITY CENTRE Limerick City 126 1 KG1 ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 127 2 KG2 ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 128 3 KJ ST LELIAS KILEELY AGE FRIENDLY COMM EDUC Limerick City 129 1 KM ST. -

Tipperary Map 2018.Pdf

Tell me a story from befo re I ca n rem OUR HOME IS YOUR HOME emb Tell me a story from before I can remember... Time For er... No matter what you’re looking for, whether it’s a Nenagh Castle, quiet night in a quaint country farmhouse; a hotel A Castles & Conquests Nenagh with leisure facilities; a cosy time in a GALWAY Time to take it all in B & B or the freedom of self-catering accommodation; it’s safe to say we’ve got the perfect A Nenagh Castle, Nenagh spot for you, while you explore our beautiful county. Nenagh Castle boasts the finest cylindrical keep Wherever you choose to stay, you’ll be welcomed in Ireland and was initially built as a military LEGEND Terryglass Belfast N52 warmly and greeted with a smile. castle between 1200 and 1220 by Theobald E The Main Guard, Clonmel 5 Fitzwalter (1st Baron Butler). This impressive medieval building is steeped in a turbulent Built by James Butler (Duke of Ormond) in history: Earls, Barons, rebels, tyrants and N65 1675 to serve as the courthouse of the Ormond Knock Lough Derg arsonists have all made an indelible mark on Palatinate, this truly historic building has had this castle’s architectural structure. The castle’s many functions over the centuries, ranging Galway Dublin Keep, which formed part of the perimeter of from a market house, barracks, public house the fortress, rises to a height of one hundred and now a museum. After almost ten years OFFALY feet, with a stone spiral stairs of 101 steps.