In Side Show

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 7, 2019 John David Smith & Micheal J

John David Smith & Micheal J. Larson General Orders No. 3-19 March 7, 2019 March 2019 Dear Delia: The Civil War Letters IN THIS ISSUE of Henry F. Young MCWRT News …………………….…………..… page 2 Seventh Wisconsin Infantry From the Archives …………..…..……………..page 3 Area Events ……………………………………….. page 3 Dear Delia chronicles the story of Henry F. Young, an officer in the From the Field ……………….…..….….... pages 4-5 famed Iron Brigade, as told through 155 letters home to his wife and In Memoriam ……………………….……………. page 5 family in southwestern Wisconsin. Words that are insightful, sometimes American Battlefield Trust …………………. page 6 poignant and powerful, enables us to witness the Civil War through Obscure Civil War Fact ………………………. page 6 Young’s eyes. Round Table Speakers 2017-2018……… page 7 Writing from Virginia, Henry Young’s devotion to Delia and his children 2018-2019 Board of Directors ……..……. page 7 is demonstrated in his letters. His letters reflect both his loneliness and Meeting Reservation Form …………….…. page 7 his worry and concern for them. Young wonders what his place is in a Between the Covers……….………….…..… page 8 world beyond the one he left in Wisconsin. Wanderings ………………………….…….. pages 9-11 Through the Looking Glass …………. page 12-13 Young covers innumerable details of military service in his letters – from Quartermaster’s Regalia ………..………… page 14 camaraderie, pettiness and thievery to the brutality of the war. He was an astute observer of military leadership, maneuvers and tactics, rumored March Meeting at a Glance troop movements and what he perceived were the strengths and The Wisconsin Club 900 W.Wisconsin Avenue weaknesses of African American soldiers. -

Special Thanks for Colleen Mcdonough and Larissa Belezos for Rehearsal Assistance

Bridgewater State University Upcoming Music Department events: Department of Music Flute Choir Concert Thursday, April 21st, 8:00pm, Horace Mann Auditorium, Boyden Hall Pop Vocal Ensemble Student Recital-Jiaying (Iris) Zhu Friday, April 22nd, 7:00pm, Horace Mann Auditorium Prof. Heather Holland, Director Chris DiBenedetto, Piano Voice Studio Recital/Opera Ensemble Sunday, April 24th, 3:00pm & 6:00pm, Horace Mann Auditorium Austin DeAndrade, Guitar Vocal Ensemble Patrick Wroge, Bass Guitar Monday, April 25th, 8:00pm, Horace Mann Auditorium Lee Dias, Drums Student Recital-Killian Kerrigan & Austin DeAndrade Tuesday, April 26th, 8:00pm, Maxwell Library Lecture Hall, Room 013 African Drumming Concert Thursday, April 28th, 8:00pm, Horace Mann Auditorium Voice Studio Recital-Prof. Leschishin & Prof. Ferrante Friday, April 29th, 7:00pm, Horace Mann Auditorium Spring Chorale Concert Sunday, May 1st, 3:00pm, Oliver Ames HS, North Easton, MA Jazz Band Concert Monday, May 2nd, 8:00pm, Horace Mann Auditorium FRIENDS OF MUSIC In order to assist talented students in the pursuit of their musical studies and professional goals, the Department of Music has established the Tuesday, April 19, 2016 Music Scholarship Fund. 8:00 pm We welcome donations of any amount for this important undertaking! Please make checks payable to BSU Foundation Horace Mann Auditorium with a note in the memo line: “Friends of Music.” Boyden Hall Mailing address: Bridgewater State University Foundation PO Box 42 Bridgewater, MA 02325 Program Bright Maureen McDonald Kate Morin and Nirorokis Guerrero Blue Skies Irving Berlin Better With A Man Steven Lutvak Full Ensemble Arranged by Roger Emerson from A Gentlemens Guide to Love and Murder Brian Kenny and Killian Kerrigan Home J. -

New York City Center Announces Re‐Opening for In‐Person Performances with Full Calendar of Programs for 2021 – 2022 Season

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: New York City Center announces re‐opening for in‐person performances with full calendar of programs for 2021 – 2022 season Dance programming highlights include Fall for Dance Festival, TWYLA NOW, and the launch of two new annual dance series Additional artistic team members for Encores! 2022 season include choreographers Camille A. Brown for The Life and Jamal Sims for Into the Woods Tickets start at $35 or less and go on sale for most performances Sep 8 for members; Sep 21 for general public July 13, 2021 (New York, NY) – New York City Center President & CEO Arlene Shuler today announced a full calendar of programming for the 2021 – 2022 season, reopening the landmark theater to the public in October 2021. This momentous return to in‐person live performances includes the popular dance and musical theater series audiences have loved throughout the years and new programs featuring iconic artists of today. Manhattan’s first performing arts center, New York City Center has presented the best in music, theater, and dance to generations of New Yorkers for over seventy‐five years. “I am delighted to announce a robust schedule of performances for our 2021 – 2022 season and once again welcome audiences to our historic theater on 55th Street,” said Arlene Shuler, President & CEO. “We have all been through so much in the past sixteen months, but with the support of the entire City Center community of artists, staff, and supporters, we have upheld our legacy of resilience and innovation, and we continue to be here for our loyal audience and the city for which we are proudly named. -

Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack Free of Charge at Public Radio Exchange, > Prx.Org > Broadway Bound *Playlist Is Listed by Show (Disc), Not in Order of Play

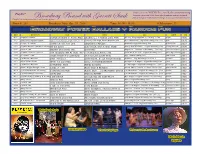

Originating on WMNR Fine Arts Radio [email protected] Playlist* Program is archived 24-48 hours after broadcast and can be heard Broadway Bound with Garrett Stack free of charge at Public Radio Exchange, > prx.org > Broadway Bound *Playlist is listed by show (disc), not in order of play. Show #: 261 Broadcast Date: Oct. 29, 2016 Time: 16:00 - 18:00 # Selections: 23 Broadway Power Ballads + Random Fun Time Writer(s) Title Artist Disc Label Year Position Comment File Number Intro Track Holiday Release Date Date Played Date Played Copy 4:02 Stephen Sondheim Everybody Ought to Have a Maid Stadlen, L.J. + Nathan Lane, Mark A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Angel 1996 4/18/1996 - 1/4/1998. 715 Perf. One 1996 Tony Award: Best Actor - Nathan Lane. CDS Funny 8 1996 1/30/10 10/29/16 7:13 Ahlert/Young; Carmichael/Loesser; Finale: I'm Gonna Sit Right Down...; Two Sleepy People; I've Got My Company: Ken Page, Amelia McQueen, Nell Ain'tForum Misbehavin' - 1996 Revival Original Broadway Broadway Cast Cast-Disc 2 RCA 5/9/1978 - 2/21/1982. 1604 perf. Three 1978 Tony Awards: Best Musical; Best CDS Aint 0:04 10/14/067/7/07 1/17/09 3/27/10 11/26/113/15/14 10/29/16 Fingers Crossed;I Can't give You Anything…; It's a Sin To Linn-Baker, Ernie Sabella 1978 2/12 McHugh/Koehler; D Fields; Mayhew; Tell…;Honeysuckle Rose. Carter, Charlene Woodard, Andre De Shields Featured Actress - Nell Carter; Best Direction. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

February 10, 2012 9:30Am & 11:30Am

SDCDArtsNotes An Educational Study Guide from San Diego Civic Dance / San Diego Park & Recreation School Shows – February 10, 2012 9:30am & 11:30am Casa del Prado Theatre, Balboa Park “It had long since come to my attention that people of accomplishment rarely sat back and let things happen to them. They went out and happened to things.” Defining Moments --Leonardo da Vinci Welcome! The San Diego Civic Dance Program welcomes you to the school-day performance of Collage 2012: Defining Moments, featuring the acclaimed dancers from the San Diego Civic Dance Company in selected numbers from their currently running theatrical performance. The City of San Diego Park and Recreation Department’s Dance Program has been lauded as the standard for which other city-wide dance programs nationwide measure themselves, and give our nearly 3,000 students the ability to work with excellent teachers in a wide variety of dance disciplines. The dancers that comprise the San Diego Civic Dance Company serve as “Dance Ambassadors” for the City of San Diego throughout the year at events as diverse as The Student Shakespeare Festival (for which they received the prize for outstanding Collage entry), Disneyland Resort and at Balboa Park’s December Nights event, to name but a few. In addition to the talented City Dance Staff, these gifted dancers also are given the opportunity to work with noted choreographers from Broadway, London’s West End, Las Vegas, and Major Motion Pictures throughout the year. Collage 2012: Defining Moments represents the culmination of choreographic efforts begun in the summer of 2011. Andrea Feier, Dance Specialist for the City of San Diego gave the choreographers a simple guideline: pick a moment, a time, or an event that inspired you – and then reflect that moment in choreography. -

Theatre for Young Audiences

Theatre for Young Audiences 2010·11 SEASON • JULIANNE ARGYROS STAGE BOOK BY AND BILLMUSIC RUSSELL BY HENRY JEFFREYKRIEGER HATCHER LYRICS BY BILL RUSSELL ORCHESTRATIONS BY HAROLD WHEELER DIRECTED AND CHOREOGRAPHED BY ART MANKE Theatre for Young Audiences Julianne Argyros Stage • February 11 - 27, 2011 LUCKY DUCK BOOK BY BILL RUSSELL AND JEFFREY HATCHER MUSIC BY HENRY KRIEGER LYRICS BY BILL RUSSELL ORCHESTRATIONS BY HAROLD WHEELER SET DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN FRED KINNEY ANGELA BALOGH CALIN JAYMI LEE SMITH SOUND DESIGN PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER CRICKET S. MYERS JACKIE S. HILL JENNIFER ELLEN BUTLER* MUSIC DIRECTOR JOHN GLAUDINI DIRECTED AND CHOREOGRAPHED BY ART MANKE VISIT SCR ONLINE! Corporate Honorary Producer of Lucky Duck www.SCR.ORg The Theatre for Young Audiences season has been made possible in part by generous grants from Be sure to check out our website for the Study Guide to The Nicholas Endowment and The Segerstrom Foundation Lucky Duck, which features additional information about the play, plus a variety of other educational resources. “Lucky Duck” is presented through special arrangement with and all authorized performance materials are supplied by Theatrical Rights Worldwide (TRW), 1359 Broadway, Suite 914, New York, N.Y. 10018 (866) 378-9758 www.theatricalrights.com DAVID EMMES MARTIN BENSON PAULA TOMEI The Cast Producing Artistic Director Artistic Director Managing Director Mildred Mallard, Wren, Priggy ................RENÉE BRNA* JOHN GLORE BIL SCHROEDER LORI MONNIER Millicent Mallard, Verblinka, Associate Artistic Director Marketing & Communications Director General Manager Chicken Little .........................GLORIA GARAYUA* SUSAN C. REEDER JOSHUA MARCHESI Development Director Production Manager Serena ...................................... JAMEY HOOD* Wolf ........................................ BRIAN IBSEN* Clem Coyote, These folks are helping run the show backstage Free-Range Chicken .... -

Indiana Dunes 2008 and Myrna Was Invited to Attend This Year (And Has Accepted) in Loving Memory of Her Husband

THE TM 911 Franklin Street Weekly Newspaper Michigan City, IN 46360 Volume 25, Number 31 Thursday, August 13, 2009 Opportunity Knocks and Entrepreneurs Answer Restoring North Franklin Street --It’s Happening Now! by Rick A. Richards There are two ways of looking at down- town Michigan City – as a glass half full or a glass half empty. Ever since major retail- ers like Sears and J.C. Penney left down- town in the 1970s for Marquette Mall, the prevailing view has been a glass half empty. Not any more. Thanks to some visionary entrepreneurs with a glass half full atti- tude, more than $2 million in development is taking place in the six blocks of Franklin Street between Fourth and 10th streets. Mike Howard, owner of Station 801, a restaurant at the corner of Eighth and Franklin streets, is excited about a resur- gent downtown. “I think one day it’s coming back,” said Howard, who with partner Jerry Peters, The original signage and some of the original glassware from the 1941-era Peters Dairy Bar that operated on Michigan Boulevard is now a part of the new recently purchased the former Argabright Peters Dairy Bar at 803 Franklin Street. Communications building at 803 Franklin St., remodeled it and opened the Cedar Sub Shop and Peters Dairy Bar. “One of the reasons we bought the build- ing is that we’re seeing things happening downtown on a positive side,” said How- ard. After purchasing the building, Howard tore out some walls, did a bit of minor re- modeling and made a phone call to Debbie Rigterink, who used to operate the Cedar Sub Shop at the Cedar Tap. -

Side Show” Is Presented Through Special Arrangement with Samuel French, Inc

Senior Acknowledgement The Somerset High School Music Department Nicole Audette Proudly Presents Stephanie Couitt Kellie Costa Cassidy Cousineau Lauren D’Alessandro Stephen Diniz Emily Domingue Jenny Lee Fortier Mason Fortier Bentley Holt Jamie Jancarik Book and Lyrics by Bill Russell Music by Henry Krieger Chelsea Leonard Orchestrations by Harold Wheeler Christopher Listenfelt Vocal & Dance Arrangements by David Chase Nathan Mendonca Original Broadway Production Directed & Choreographed by Robert Longbottom Jana Moroff Original Broadway Production Produced by Emanuel Azenberg, Joseph Nederlander, Herschel Waxman, Janice McKenna & Scott Nederlander Kelly Neufell Thomas Patten Directed by Tyler Rebello Richard J. Sylvia & Lennie Machado Rachel Smith Assistant Director & Pit Orchestra Director Derrick Souza David M. Marshall Michael Tremblay Starring Lauren Valcourt Lauren Valcourt Sarah Mayer Michael Tremblay Andrew DaCosta Thomas Patten and Christopher Crider-Plonka Jared Wright May 1, 2009 @ 7:00 p.m. – May 2, 2009 @ 7:00 p.m. – May 3, 2009 @ 2:00 p.m. Somerset High School Auditorium “Side Show” is presented through special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. All authorized performance materials are also supplied by Samuel French, Inc.. 45 West 25th Street, New York, NY 10010-2751 Phone: (212) 206-8990 Fax: (212) 206-1429 Administration The Spirit of Music … On The Move At Somerset High School … R.W. Pineault, Principal SPS Superintendant of Schools ....................................... Mr. Richard Medeiros SHS Principal ................................................................................... Mr. R.W. Pineault The spirit of music is alive at Somerset High School twelve months a SHS Vice-Principal ............................................................................... Mr. Kyle Alves SHS Vice-Principal .................................................................. Mrs. Pauline Camara year. During the warm months of summer, our students can be found SPS Coordinator of the Fine & Performing Arts .......... -

Download This 5-Year Collection of Project Programs

SHOW PROGRAMS 2011-2015 The 52nd Street Project gratefully acknowledges the support of the following foundations and corporations: BGC; Big Wood Foundation; Bloomberg; Carnegie Corporation of New York; CBS Corporation; Consolidated Edison; The Neil V. DeSena Foundation; The Dramatists Guild Fund; Dramatists Play Service; Eleanor, Adam & Mel Du- bin Foundation; The Educational Foundation Of America; Flexis Capital LLC; Sidney E. Frank Foundation; Fund for the City of New York; Grant’s Financial Publishing, Inc.; The William and Mary Greve Foundation; Heisman Foundation; The Henlopen Foundation; The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation; Hudson Scenic Studio; I. Weiss; Integra Realty; The Suzanne Nora Johnson & David G. Johnson Foundation; Ann M. Martin Foundation; J.P. Mor- gan Charitable Trust; MTI; National Philanthropic Trust; NYFA; Punchline Magazine; Jonathan Rose Companies; The Shubert Organization; Simon & Eisenberg; St. Vincent De Paul Foundation; Harold & Mimi Steinberg Chari- table Trust; Stranahan Foundation; Susquehanna Foundation, Corp.; Tax Pro Financial Network, Inc.; Theater Subdistrict Council; Theatre Communications Group, Inc.; Tiger Baron Foundation; United Real Estate Ventures, Inc.; Van Deusen Family Fund; Watkins, Inc.; Yorke Construction Corp. In addition, the following individuals made gifts over $250 to The 52nd Street Project this past year. (list current as of 12/09/10): Robert Abrams & Arthur Dantchik Kevin Kelly David & Laura Ross Cynthia Vance Cathy Dantchik Patrick & Diane Kelly Carla Sacks & John Morris George -

BTW.C.Schedule2017(MH Edit)

Broadway Teachers Workshop C 2017 Schedule (*subject to change) Thursday, July 13, 2017 Today’s workshops are held at The Sheen Center; 18 Bleecker Street, New York, NY 10012 9:15 a.m. – 10:00 a.m. Registration/ Welcome/ Meet and Greet Your Peers 10:00 a.m. – 11:30 a.m. Opening Session: Creativity and Connection: with Susan Blackwell ([title of show]) In this fun, festive welcome session, Susan Blackwell kicks off your Broadway Teachers Workshop with a bang! This year's theme is CREATIVITY and--as always--the discussion will be spirited, the ideas shared will be inspiring, and the connections made will lay the foundation for a warm, wonderful BTW adventure! Susan Blackwell is on a mission to free people’s creativity and self-expression. She champions this cause as a performer, writer, educator and business consultant. She played a character based on herself in the original Broadway musical [title of show} and the Off-Broadway musical Now. Here. This. She created and hosts the freewheeling chat show ‘Side by Side by Susan Blackwell’ on Broadway.com. As the founder of Susan Blackwell & Co., she partners with like-minded compassionate artists and thought leaders to deliver inspiring entertainment and educational offerings aimed at freeing people’s creativity and self-expression. 11:45 a.m. – 1:00 p.m. A.) EXPLORING FRANK LOESSER: A concert and class with Broadway Music Director David Loud Join Broadway Music Director David Loud (Scottsboro Boys, Curtains, The Visit) in another of his delightful inquiries into the songs of our greatest theatre composers. -

Masculine Interludes: Monstrosity and Compassionate Manhood in American Literature, 1845-1899

MASCULINE INTERLUDES: MONSTROSITY AND COMPASSIONATE MANHOOD IN AMERICAN LITERATURE, 1845-1899 BY Carey R. Voeller Ph.D., University of Kansas 2008 Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chair, Susan K. Harris ______________________________ Phillip Barnard ______________________________ Laura Mielke ______________________________ Dorice Elliott ______________________________ Tanya Hart Date Defended: June 30, 2008 ii The Dissertation Committee for Carey R. Voeller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: MASCULINE INTERLUDES: MONSTROSITY AND COMPASSIONATE MANHOOD IN AMERICAN LITERATURE, 1845-1899 Committee: ______________________________ Chair, Susan K. Harris ______________________________ Phillip Barnard ______________________________ Laura Mielke ______________________________ Dorice Elliott ______________________________ Tanya Hart Date Approved: June 30, 2008 iii Abstract This dissertation examines the textual formulation of “compassionate manhood”—a kind, gentle trope of masculinity—in nineteenth-century American literature. George Lippard, Mark Twain, J. Quinn Thornton, and Stephen Crane utilize figures who physically and morally deviate from the “norm” to promote compassionate manhood in texts that illustrate dominant constructions of masculinity structured on aggressive individualism. Compassionate manhood operates through