Dead Storage As a Barrier to Efficient Electronic Waste

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embedded Linux Systems with the Yocto Project™

OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT SERIES Embedded Linux Systems with the Yocto Project" FREE SAMPLE CHAPTER SHARE WITH OTHERS �f, � � � � Embedded Linux Systems with the Yocto ProjectTM This page intentionally left blank Embedded Linux Systems with the Yocto ProjectTM Rudolf J. Streif Boston • Columbus • Indianapolis • New York • San Francisco • Amsterdam • Cape Town Dubai • London • Madrid • Milan • Munich • Paris • Montreal • Toronto • Delhi • Mexico City São Paulo • Sidney • Hong Kong • Seoul • Singapore • Taipei • Tokyo Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. The author and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. For information about buying this title in bulk quantities, or for special sales opportunities (which may include electronic versions; custom cover designs; and content particular to your business, training goals, marketing focus, or branding interests), please contact our corporate sales depart- ment at [email protected] or (800) 382-3419. For government sales inquiries, please contact [email protected]. For questions about sales outside the U.S., please contact [email protected]. Visit us on the Web: informit.com Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress. -

E-Waste Generation from Mobile Phones and Sustainability Issues for Designers

RPS Research into Design — Supporting Sustainable Product Development “icord2011-lineup” 2010/12/24 523 E-WASTE GENERATION FROM MOBILE PHONES AND SUSTAINABILITY ISSUES FOR DESIGNERS Pradeep G. Yammiyavara and Vikash Kumarb 1Department of Design, IIT Guwahati, Assam, India. Email: [email protected], [email protected] Recent contribution of mobile phones as e-waste generators is a matter of concern due to the product’s shorter lifespan, large disposal volume, toxic nature of materials, higher energy requirement at production stage etc. With the predicted exponential penetration of mobile phones in countries such as India and China e-waste is likely to nullify the benefits unless properly approached. Addressing these concerns the first part of this paper attempts to estimate the volume of e-waste generated by mobile phones. Identification of key issues impacting the sustainability of mobile phones is discussed in the second part using product samples. This paper is an attempt to understand issues involved in sustainable design and explore possible methods of addressing sustainability at the designing stage of a product. Keywords: E-waste, Mobile phones, Design for sustainability, Culture. 1. INTRODUCTION Common understanding of the term e-waste, or electronic waste, is old, end-of-life electronic appliances such as computers, laptops, TVs, DVD players, mobile phones, mp3 players etc; which have been disposed of by their original users. Technically, electronic waste is only a subset of WEEE (Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment) as defined by OECD (Organization for Economic Co- operation and Development) as any appliance that uses an electric power supply and has reached its end-of-life [1]. -

Node Layout of Recycling Network for Cell Phones in China Under the Third Party Logistics

International Journal of u- and e- Service, Science and Technology Vol.8, No. 9 (2015), pp.1-12 http://dx.doi.org/10.14257/ijunesst.2015.8.9.01 Node Layout of Recycling Network for Cell Phones in China under the Third Party Logistics Danning Li1, Xianliang Shi1 and Chunhua Shi2 1School of Economics and Management, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 100044 2Higher Education Press, Beijing, China, 100029 [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract With the increasing acceleration of updating rate for mobile phones in China, the processing procedure of cell phones has aroused a problem for the whole society. Meantime, environmental pollution and waste of resources result from improper processing approaches of such products. In this paper, the processing modes and corresponding reverse logistics network are analyzed scientifically and completely in terms of recycling by the third party reverse logistics enterprises. Then, a mathematical programming model is proposed in the case of multi-varieties phones and stochastic circumstances to handle the problem of node arrangement and facility location, which taking both cost objective and environment objective into consideration. To combat the model, we design a hybrid intelligent algorithm consisting of genetic algorithm, stochastic simulation and linear programming. Finally a numerical example validates the feasibility of the model and sensitivity analysis is conducted to illustrate its reliability. Such method can be treated as a practice guideline and some suggestions regarding the layout construction are put forward in the end. Keywords: The third party reverses logistics, node layout, stochastic circumstances, multi-objective programming, hybrid intelligent algorithm 1. -

The True Environmental Impact of Smartphones?

Int J Life Cycle Assess (2015) 20:1181–1196 DOI 10.1007/s11367-015-0909-4 UNCERTAINTIES IN LCA Redefining scope: the true environmental impact of smartphones? James Suckling1 & Jacquetta Lee1 Received: 3 September 2014 /Accepted: 19 May 2015 /Published online: 10 June 2015 # The Author(s) 2015. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract impact from 8.5 to 18.0 kg CO2-eq, other phases are less Purpose The aim of this study is to explore the literature sur- affected. Addition of the network increases the use phase by rounding the environmental impact of mobile phones and the another 24.7 kg CO2-eq. In addition, it is shown that take-back implications of moving from the current business model of of mobile phones is not effective at present and that prompt selling, using and discarding phones to a product service sys- return of the phones could result in reduction in impact by best tem based upon a cloud service. The exploration of the im- reuse potential and further reduction in toxic emissions pacts relating to this shift and subsequent change in scope is through inappropriate disposal. explored in relation to the life cycle profile of a typical Conclusions The way in which consumers interact with their smartphone. phones is changing, leading to a system which is far more Methods A literature study is conducted into the existing lit- integrated with the internet. A product service system based erature in order to define the characteristics of a Btypical^ upon a cloud service highlights the need for improved energy smartphone. -

Nasdaq Capital Market Friday, December 28, 2018 5:32 PM

Nasdaq Capital Market Friday, December 28, 2018 5:32 PM Name Symbol Close 3PEA International TPNL 3.35 Abeona Therapeutics ABEO 7.02 Ability ABIL 2.02 Abraxas Petroleum AXAS 1.08 Acasti Pharma ACST 0.73 Accelerate Diagnostics AXDX 11.78 Acer Therapeutics ACER 18.25 Achieve Life Sciences ACHV 1.2 ACNB ACNB 38.73 Adamis Pharmaceuticals ADMP 2.1 Adesto Technologies IOTS 4.3 ADial Pharmaceuticals ADIL 5.55 ADMA Biologics ADMA 2.23 ADOMANI ADOM 0.25 Aehr Test Systems AEHR 1.44 Aerpio Pharmaceuticals ARPO 1.71 AEterna Zentaris AEZS 2.97 Aethlon Medical AEMD 1.52 Agenus AGEN 2.39 AGM Group Holdings AGMH 28.05 Airgain AIRG 10.04 AirMedia Group ADR AMCN 0.24 Air T AIRT 24.03 Akari Therapeutics ADR AKTX 1.63 Akers Biosciences AKER 1.27 Akoustis Technologies AKTS 4.79 Alberton Acquisition Cl A ALAC 9.8 Alberton Acquisition WT ALACW 0.12 Albireo Pharma ALBO 23.18 Aldeyra Therapeutics ALDX 8 Alithya Group Cl A ALYA 2.55 Alkaline Water WTER 3.24 Allegro Merger Rt ALGRR 0.3 Alliance MMA AMMA 0.17 Allied Healthcare Products AHPI 1.89 Alliqua BioMedical ALQA 2 Alta Mesa Resources AMR 1 Alta Mesa Resources WT AMRWW 0.08 Altus Midstream ALTM 7.75 AMCI Acquisition AMCIU 9.95 American Electric Technologies AETI 0.89 Ameri Holdings AMRH 0.17 Ameri Holdings WT AMRHW 0.03 Ames National ATLO 25.72 Anavex Life Sciences AVXL 1.52 Anixa Biosciences ANIX 4 Antares Pharma ATRS 2.63 Apollo Medical Holdings AMEH 20.73 Appliance Recycling Centers of ARCI 0.5 America Applied DNA Sciences APDN 0.38 Applied DNA Sciences WT APDNW .. -

Ecodesign Preparatory Study on Mobile Phones, Smartphones and Tablets

Ecodesign preparatory study on mobile phones, smartphones and tablets Draft Task 4 Report Technologies Written by Fraunhofer IZM, Fraunhofer ISI, VITO October – 2020 Authors: Karsten Schischke (Fraunhofer IZM) Christian Clemm (Fraunhofer IZM) Anton Berwald (Fraunhofer IZM) Marina Proske (Fraunhofer IZM) Gergana Dimitrova (Fraunhofer IZM) Julia Reinhold (Fraunhofer IZM) Carolin Prewitz (Fraunhofer IZM) Christoph Neef (Fraunhofer ISI) Contributors: Antoine Durand (Quality control, Fraunhofer ISI) Clemens Rohde (Quality control, Fraunhofer ISI) Simon Hirzel (Quality control, Fraunhofer ISI) Mihaela Thuring (Quality control, contract management, VITO) Study website: https://www.ecosmartphones.info EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs Directorate C — Sustainable Industry and Mobility DDG1.C.1 — Circular Economy and Construction Contact: Davide Polverini E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels 2 Ecodesign preparatory study on mobile phones, smartphones and tablets Draft Task 4 Report Technologies 4 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020 ISBN number doi:number © European Union, 2020 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. -

HP Color Laserjet Pro MFP M277 User Guide

Color LaserJet Pro MFP M277 User Guide www.hp.com/support/colorljMFPM277 HP Color LaserJet Pro MFP M277 User Guide Copyright and License Trademark Credits © Copyright 2019 HP Development Company, Adobe®, Adobe Photoshop®, Acrobat®, and L.P. PostScript® are trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated. Reproduction, adaptation, or translation without prior written permission is prohibited, except as Apple and the Apple logo are trademarks of allowed under the copyright laws. Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. iPod is a trademark of Apple The information contained herein is subject to Computer, Inc. iPod is for legal or rightholder- change without notice. authorized copying only. Don't steal music. The only warranties for HP products and Microsoft®, Windows®, Windows® XP, and services are set forth in the express warranty Windows Vista® are U.S. registered trademarks statements accompanying such products and of Microsoft Corporation. services. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting an additional warranty. HP shall not UNIX® is a registered trademark of The Open be liable for technical or editorial errors or Group. omissions contained herein. Edition 3, 8/2019 Table of contents 1 Product overview ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Product views ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

End-Of-Life Strategies for Used Mobile Phones Using Material Flow Modeling

recycling Article End-of-Life Strategies for Used Mobile Phones Using Material Flow Modeling Kuniko Mishima 1,*, Michele Rosano 2, Nozomu Mishima 3 and Hidekazu Nishimura 1 1 Graduate School of System Design and Management, Keio University, Yokohama 223-8526, Japan; [email protected] 2 Sustainable Engineering Group, Curtin University, Perth, WA 6845, Australia; [email protected] 3 Graduate School of Engineering and Resource Science, Akita University, Akita 010-8502, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +81-29-827-1171 Academic Editor: William Bullock Received: 20 January 2016; Accepted: 2 February 2016; Published: 6 February 2016 Abstract: In order to secure valuable materials and to establish better circular economy practice, new legislation to promote recycling of small-sized e-waste including used mobile phones started in April 2013, in Japan. In order to consider appropriate methods to reduce material usage in mobile phone production, an examination of appropriate strategies in handling used mobile phone products is warranted. This paper investigates an analysis of material flow model for used mobile phones. Then, by analyzing the model, it tries to find suitable strategies to reduce the material consumption associated with mobile phone production and consumption. Although material recycling is an important strategy in Japan, other waste management options exist. This research indicates which factors are keys in reducing material consumption and CO2 emission, and establishing resource efficient production. The study concludes that “domestic product reuse” and “official recycling networks” are equally good in reducing the consumption of virgin materials associated with mobile phone production. -

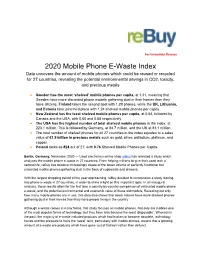

2020 Mobile Phone E-Waste Index

For Immediate Release 2020 Mobile Phone E-Waste Index Data uncovers the amount of mobile phones which could be reused or recycled for 27 countries, revealing the potential environmental savings in CO2, toxicity, and precious metals ● Sweden has the most ‘shelved’ mobile phones per capita, at 1.31, meaning that Swedes have more discarded phone models gathering dust in their homes than they have citizens. Finland takes the second spot with 1.29 phones, while the UK, Lithuania, and Estonia take joint third place with 1.24 shelved mobile phones per capita. ● New Zealand has the least shelved mobile phones per capita, at 0.54, followed by Canada and the USA, with 0.60 and 0.68 respectively. ● The USA has the highest number of total shelved mobile phones in the index, at 223.1 million. This is followed by Germany, at 84.7 million, and the UK at 83.1 million. ● The total number of shelved phones for all 27 countries in the index equates to a sales value of €1.9 billion in precious metals such as gold, silver, palladium, platinum, and copper. ● Poland ranks as #24 out of 27, with 0.76 Shelved Mobile Phones per Capita. Berlin, Germany, November 2020 — Used electronics online shop reBuy has released a study which analyses the mobile phone e-waste in 27 countries. From helping millions to give their used tech a second life, reBuy has become increasingly aware of the sheer volume of perfectly functional but unwanted mobile phones gathering dust in the back of cupboards and drawers. With the largest shopping period of the year approaching, reBuy decided to commission a study looking into phone e-waste in 27 countries, in order to shine a light on this important topic. -

Telenor in Norway Introduces Mobile Phone Recycling for the Sake of the Environment: New Trees for Old Phones

Telenor in Norway introduces mobile phone recycling for the sake of the environment: New trees for old phones Now you can return your old phone. Telenor in Norway is introducing a buyback/recycling scheme for mobile phones. To thank you for helping, you will get 50 free SMSes and the Red Cross plants 25 trees in Asia, for every phone you hand in. According to Telenor's calculations at least four million used mobile phones are lying around collecting dust in Norwegian homes. Presently 82 per cent of Norwegian households have at least one mobile phone extra that they are not using. It is only a dismal 12 per cent of consumers that recycle mobile phones. Since mobile phones are not being returned for recycling, mobile phone manufacturers are forced to extract new materials, in stead of just using the resources already available in used mobile phones. Telenor wants to do something about this and introduces a new mobile recycling scheme. This lack of recycling suggests that the majority of Norwegians really have no idea what they can do with used mobile phones. Many keep old phones in reserve as a back-up. Norwegians change phones every two years on average. This means that fully usable phones are lying around in Norwegian homes. "Telenor wants to help consumers dispose of mobile phones in a safe, secure and environmentally friendly manner. Of the phones collected those damaged will be recycled. Those that can be repaired will be sold in Asia which is a well-functioning market for used goods. Proceeds from the sales will be given to the Red Cross. -

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPAC) Market Report

SPAC Market Report Fall 2020 MARKET REPORT Special Purpose Acquisition Companies F a l l 2 0 2 0 1 SPAC Market Report Fall 2020 SPAC MARKET Highlights STATISTICS* The special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) market has boomed over the past several years, with continued increases in IPO activity 262 262 IPOs, totaling over $74 billion and record completions of de-SPAC transactions. Through September 30, 2020: 90 90 de-SPAC transactions completed Since January 1, 2017, 90 de-SPAC transactions have been completed, totaling over $90 billion of transaction enterprise value. An additional 44 de- Over $90 billion of total enterprise SPAC transactions are currently pending. $90+ value in completed de-SPAC transactions There are 150 SPACs actively seeking acquisition targets, representing over $48 billion of IPO proceeds, or approximately 65% of all SPAC IPO 150 SPACs currently active and proceeds since the beginning of 2017. 150 seeking targets An additional 55 SPACs are preparing for IPOs, demonstrating the continued growth of the SPAC *Data presented from January 1, 2017 to September 30, 2020 market. 2 Source: S&P Capital IQ; SPAC Insider SPAC Market Report Fall 2020 SPAC Market Activity IPO ACTIVITY 160 152 $70,000 ▪ SPAC IPO activity has soared past all time highs As of: 10/23/2020 with the number of IPOs year-to-date at nearly 3x 140 $60,000 the 2019 total and proceeds year-to-date are 120 $50,000 greater than the aggregate from the last decade. 100 $40,000 80 ▪ IPOs have been raising record proceeds with an 59 $30,000 average of nearly $370 million per SPAC IPO and 60 46 some raises into the billions of dollars. -

Improving Hydrometallurgical Methods for Processing Tin

1021 A publication of CHEMICAL ENGINEERING TRANSACTIONS VOL. 81, 2020 The Italian Association of Chemical Engineering Online at www.cetjournal.it Guest Editors: Petar S. Varbanov, Qiuwang Wang, Min Zeng, Panos Seferlis, Ting Ma, Jiří J. Klemeš Copyright © 2020, AIDIC Servizi S.r.l. DOI: 10.3303/CET2081171 ISBN 978-88-95608-79-2; ISSN 2283-9216 Improving Hydrometallurgical Methods for Processing Tin- containing Electronic Waste Ruslan Viktorovich Sapinova*, Marzhan Anuarbekovna Sadenovaa, Natalya Anatolyevna Kulenovaa, Natalya Vasilievna Oleinikovab a Priority Department Centre «Veritas», D. Serikbayev East Kazakhstan State Technical University, 19, Serikbayev str. 070000, Ust-Kamenogorsk, Kazakhstan b School of Non-Ferrous Metals and Material Science,Siberian Federal University,"Krasnoyarsk worker", 95, 660025, Krasnoyarsk, Russian Federation [email protected] This article provides an overview of methods for processing electronic waste (mobile phones, smartphones, printed circuit boards). The possibility of extracting tin from the waste of printed circuit boards of mobile phones using hydrochloric acid is shown. Established that the deposition of tin from the productive solution occurs due to cementation - an electrochemical displacement reaction between a cementing metal (aluminum) and a cemented ion (tin). The possibility of intensification of the process using a vibrating installation is evaluated. An environmentally friendly and efficient method for processing tin-containing electronic waste is proposed. 1. Introduction According to preliminary data from the analytical company Gartner, the release of smartphones in 2019 amounted to 1.5∙109 units (Gartner, 2019). At the same time, according to forecasts by the International Data Corporation (IDC), the market for high-tech devices in the field of information technology (IT) will lose $ 30∙109 over the next 5 y due to a decrease in sales of personal computers (PCs) and will decrease by a third within 10 y.