Centripetal Force in Terms of Angular Velocity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 11 Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) 11-1 Motion about a Fixed Axis The motion of the flywheel of an engine and of a pulley on its axle are examples of an important type of motion of a rigid body, that of the motion of rotation about a fixed axis. Consider the motion of a uniform disk rotat ing about a fixed axis passing through its center of gravity C perpendicular to the face of the disk, as shown in Figure 11-1. The motion of this disk may be de scribed in terms of the motions of each of its individual particles, but a better way to describe the motion is in terms of the angle through which the disk rotates. -

PHYSICS of ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY Angie Bukley1, William Paloski,2 and Gilles Clément1,3

Chapter 2 PHYSICS OF ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY Angie Bukley1, William Paloski,2 and Gilles Clément1,3 1 Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, USA 2 NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, Texas, USA 3 Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Toulouse, France This chapter discusses potential technologies for achieving artificial gravity in a space vehicle. We begin with a series of definitions and a general description of the rotational dynamics behind the forces ultimately exerted on the human body during centrifugation, such as gravity level, gravity gradient, and Coriolis force. Human factors considerations and comfort limits associated with a rotating environment are then discussed. Finally, engineering options for designing space vehicles with artificial gravity are presented. Figure 2-01. Artist's concept of one of NASA early (1962) concepts for a manned space station with artificial gravity: a self- inflating 22-m-diameter rotating hexagon. Photo courtesy of NASA. 1 ARTIFICIAL GRAVITY: WHAT IS IT? 1.1 Definition Artificial gravity is defined in this book as the simulation of gravitational forces aboard a space vehicle in free fall (in orbit) or in transit to another planet. Throughout this book, the term artificial gravity is reserved for a spinning spacecraft or a centrifuge within the spacecraft such that a gravity-like force results. One should understand that artificial gravity is not gravity at all. Rather, it is an inertial force that is indistinguishable from normal gravity experience on Earth in terms of its action on any mass. A centrifugal force proportional to the mass that is being accelerated centripetally in a rotating device is experienced rather than a gravitational pull. -

LECTURES 20 - 29 INTRODUCTION to CLASSICAL MECHANICS Prof

LECTURES 20 - 29 INTRODUCTION TO CLASSICAL MECHANICS Prof. N. Harnew University of Oxford HT 2017 1 OUTLINE : INTRODUCTION TO MECHANICS LECTURES 20-29 20.1 The hyperbolic orbit 20.2 Hyperbolic orbit : the distance of closest approach 20.3 Hyperbolic orbit: the angle of deflection, φ 20.3.1 Method 1 : using impulse 20.3.2 Method 2 : using hyperbola orbit parameters 20.4 Hyperbolic orbit : Rutherford scattering 21.1 NII for system of particles - translation motion 21.1.1 Kinetic energy and the CM 21.2 NII for system of particles - rotational motion 21.2.1 Angular momentum and the CM 21.3 Introduction to Moment of Inertia 21.3.1 Extend the example : J not parallel to ! 21.3.2 Moment of inertia : mass not distributed in a plane 21.3.3 Generalize for rigid bodies 22.1 Moment of inertia tensor 2 22.1.1 Rotation about a principal axis 22.2 Moment of inertia & energy of rotation 22.3 Calculation of moments of inertia 22.3.1 MoI of a thin rectangular plate 22.3.2 MoI of a thin disk perpendicular to plane of disk 22.3.3 MoI of a solid sphere 23.1 Parallel axis theorem 23.1.1 Example : compound pendulum 23.2 Perpendicular axis theorem 23.2.1 Perpendicular axis theorem : example 23.3 Example 1 : solid ball rolling down slope 23.4 Example 2 : where to hit a ball with a cricket bat 23.5 Example 3 : an aircraft landing 24.1 Lagrangian mechanics : Introduction 24.2 Introductory example : the energy method for the E of M 24.3 Becoming familiar with the jargon 24.3.1 Generalised coordinates 24.3.2 Degrees of Freedom 24.3.3 Constraints 3 24.3.4 Configuration -

Centripetal Force Is Balanced by the Circular Motion of the Elctron Causing the Centrifugal Force

STANDARD SC1 b. Construct an argument to support the claim that the proton (and not the neutron or electron) defines the element’s identity. c. Construct an explanation based on scientific evidence of the production of elements heavier than hydrogen by nuclear fusion. d. Construct an explanation that relates the relative abundance of isotopes of a particular element to the atomic mass of the element. First, we quickly review pre-requisite concepts One of the most curious observations with atoms is the fact that there are charged particles inside the atom and there is also constant spinning and Warm-up 1: List the name, charge, mass, and location of the three subatomic circling. How does atom remain stable under these conditions? Remember particles Opposite charges attract each other; Like charges repel each other. Your Particle Location Charge Mass in a.m.u. Task: Read the following information and consult with your teacher as STABILITY OF ATOMS needed, answer Warm-Up tasks 2 and 3 on Page 2. (3) Death spiral does not occur at all! This is because the centripetal force is balanced by the circular motion of the elctron causing the centrifugal force. The centrifugal force is the outward force from the center to the circumference of the circle. Electrons not only spin on their own axis, they are also in a constant circular motion around the nucleus. Despite this terrific movement, electrons are very stable. The stability of electrons mainly comes from the electrostatic forces of attraction between the nucleus and the electrons. The electrostatic forces are also known as Coulombic Forces of Attraction. -

Linear and Angular Velocity Examples

Linear and Angular Velocity Examples Example 1 Determine the angular displacement in radians of 6.5 revolutions. Round to the nearest tenth. Each revolution equals 2 radians. For 6.5 revolutions, the number of radians is 6.5 2 or 13 . 13 radians equals about 40.8 radians. Example 2 Determine the angular velocity if 4.8 revolutions are completed in 4 seconds. Round to the nearest tenth. The angular displacement is 4.8 2 or 9.6 radians. = t 9.6 = = 9.6 , t = 4 4 7.539822369 Use a calculator. The angular velocity is about 7.5 radians per second. Example 3 AMUSEMENT PARK Jack climbs on a horse that is 12 feet from the center of a merry-go-round. 1 The merry-go-round makes 3 rotations per minute. Determine Jack’s angular velocity in radians 4 per second. Round to the nearest hundredth. 1 The merry-go-round makes 3 or 3.25 revolutions per minute. Convert revolutions per minute to radians 4 per second. 3.25 revolutions 1 minute 2 radians 0.3403392041 radian per second 1 minute 60 seconds 1 revolution Jack has an angular velocity of about 0.34 radian per second. Example 4 Determine the linear velocity of a point rotating at an angular velocity of 12 radians per second at a distance of 8 centimeters from the center of the rotating object. Round to the nearest tenth. v = r v = (8)(12 ) r = 8, = 12 v 301.5928947 Use a calculator. The linear velocity is about 301.6 centimeters per second. -

Measuring Inertial, Centrifugal, and Centripetal Forces and Motions The

Measuring Inertial, Centrifugal, and Centripetal Forces and Motions Many people are quite confused about the true nature and dynamics of cen- trifugal and centripetal forces. Some believe that centrifugal force is a fictitious radial force that can’t be measured. Others claim it is a real force equal and opposite to measured centripetal force. It is sometimes thought to be a continu- ous positive acceleration like centripetal force. Crackpot theorists ignore all measurements and claim the centrifugal force comes out of the aether or spa- cetime continuum surrounding a spinning body. The true reality of centripetal and centrifugal forces can be easily determined by simply measuring them with accelerometers rather than by imagining metaphysical assumptions. The Momentum and Energy of the Cannon versus a Cannonball Cannon Ball vs Cannon Momentum and Energy Force = mass x acceleration ma = Momentum = mv m = 100 kg m = 1 kg v = p/m = 1 m/s v = p/m = 100 m/s p = mv 100 p = mv = 100 energy = mv2/2 = 50 J energy = mv2/2 = 5,000 J Force p = mv = p = mv p=100 Momentum p = 100 Energy mv2/2 = mv2 = mv2/2 Cannon ball has the same A Force always produces two momentum as the cannon equal momenta but it almost but has 100 times more never produces two equal kinetic energy. quantities of kinetic energy. In the following thought experiment with a cannon and golden cannon ball, their individual momentum is easy to calculate because they are always equal. However, the recoil energy from the force of the gunpowder is much greater for the ball than the cannon. -

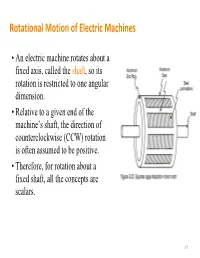

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines • An electric machine rotates about a fixed axis, called the shaft, so its rotation is restricted to one angular dimension. • Relative to a given end of the machine’s shaft, the direction of counterclockwise (CCW) rotation is often assumed to be positive. • Therefore, for rotation about a fixed shaft, all the concepts are scalars. 17 Angular Position, Velocity and Acceleration • Angular position – The angle at which an object is oriented, measured from some arbitrary reference point – Unit: rad or deg – Analogy of the linear concept • Angular acceleration =d/dt of distance along a line. – The rate of change in angular • Angular velocity =d/dt velocity with respect to time – The rate of change in angular – Unit: rad/s2 position with respect to time • and >0 if the rotation is CCW – Unit: rad/s or r/min (revolutions • >0 if the absolute angular per minute or rpm for short) velocity is increasing in the CCW – Analogy of the concept of direction or decreasing in the velocity on a straight line. CW direction 18 Moment of Inertia (or Inertia) • Inertia depends on the mass and shape of the object (unit: kgm2) • A complex shape can be broken up into 2 or more of simple shapes Definition Two useful formulas mL2 m J J() RRRR22 12 3 1212 m 22 JRR()12 2 19 Torque and Change in Speed • Torque is equal to the product of the force and the perpendicular distance between the axis of rotation and the point of application of the force. T=Fr (Nm) T=0 T T=Fr • Newton’s Law of Rotation: Describes the relationship between the total torque applied to an object and its resulting angular acceleration. -

Action Principle for Hydrodynamics and Thermodynamics, Including General, Rotational Flows

th December 15, 2014 Action Principle for Hydrodynamics and Thermodynamics, including general, rotational flows C. Fronsdal Depart. of Physics and Astronomy, University of California Los Angeles 90095-1547 USA ABSTRACT This paper presents an action principle for hydrodynamics and thermodynamics that includes general, rotational flows, thus responding to a challenge that is more that 100 years old. It has been lifted to the relativistic context and it can be used to provide a suitable source of rotating matter for Einstein’s equation, finally overcoming another challenge of long standing, the problem presented by the Bianchi identity. The new theory is a combination of Eulerian and Lagrangian hydrodynamics, with an extension to thermodynamics. In the first place it is an action principle for adia- batic systems, including the usual conservation laws as well as the Gibbsean variational principle. But it also provides a framework within which dissipation can be introduced in the usual way, by adding a viscosity term to the momentum equation, one of the Euler-Lagrange equations. The rate of the resulting energy dissipation is determined by the equations of motion. It is an ideal framework for the description of quasi-static processes. It is a major development of the Navier-Stokes-Fourier approach, the princi- pal advantage being a hamiltonian structure with a natural concept of energy as a first integral of the motion. Two velocity fields are needed, one the gradient of a scalar potential, the other the time derivative of a vector field (vector potential). Variation of the scalar potential gives the equation of continuity and variation of the vector potential yields the momentum equation. -

Physics B Topics Overview ∑

Physics 106 Lecture 1 Introduction to Rotation SJ 7th Ed.: Chap. 10.1 to 3 • Course Introduction • Course Rules & Assignment • TiTopics Overv iew • Rotation (rigid body) versus translation (point particle) • Rotation concepts and variables • Rotational kinematic quantities Angular position and displacement Angular velocity & acceleration • Rotation kinematics formulas for constant angular acceleration • Analogy with linear kinematics 1 Physics B Topics Overview PHYSICS A motion of point bodies COVERED: kinematics - translation dynamics ∑Fext = ma conservation laws: energy & momentum motion of “Rigid Bodies” (extended, finite size) PHYSICS B rotation + translation, more complex motions possible COVERS: rigid bodies: fixed size & shape, orientation matters kinematics of rotation dynamics ∑Fext = macm and ∑ Τext = Iα rotational modifications to energy conservation conservation laws: energy & angular momentum TOPICS: 3 weeks: rotation: ▪ angular versions of kinematics & second law ▪ angular momentum ▪ equilibrium 2 weeks: gravitation, oscillations, fluids 1 Angular variables: language for describing rotation Measure angles in radians simple rotation formulas Definition: 360o 180o • 2π radians = full circle 1 radian = = = 57.3o • 1 radian = angle that cuts off arc length s = radius r 2π π s arc length ≡ s = r θ (in radians) θ ≡ rad r r s θ’ θ Example: r = 10 cm, θ = 100 radians Æ s = 1000 cm = 10 m. Rigid body rotation: angular displacement and arc length Angular displacement is the angle an object (rigid body) rotates through during some time interval..... ...also the angle that a reference line fixed in a body sweeps out A rigid body rotates about some rotation axis – a line located somewhere in or near it, pointing in some y direction in space • One polar coordinate θ specifies position of the whole body about this rotation axis. -

6. Non-Inertial Frames

6. Non-Inertial Frames We stated, long ago, that inertial frames provide the setting for Newtonian mechanics. But what if you, one day, find yourself in a frame that is not inertial? For example, suppose that every 24 hours you happen to spin around an axis which is 2500 miles away. What would you feel? Or what if every year you spin around an axis 36 million miles away? Would that have any e↵ect on your everyday life? In this section we will discuss what Newton’s equations of motion look like in non- inertial frames. Just as there are many ways that an animal can be not a dog, so there are many ways in which a reference frame can be non-inertial. Here we will just consider one type: reference frames that rotate. We’ll start with some basic concepts. 6.1 Rotating Frames Let’s start with the inertial frame S drawn in the figure z=z with coordinate axes x, y and z.Ourgoalistounderstand the motion of particles as seen in a non-inertial frame S0, with axes x , y and z , which is rotating with respect to S. 0 0 0 y y We’ll denote the angle between the x-axis of S and the x0- axis of S as ✓.SinceS is rotating, we clearly have ✓ = ✓(t) x 0 0 θ and ✓˙ =0. 6 x Our first task is to find a way to describe the rotation of Figure 31: the axes. For this, we can use the angular velocity vector ! that we introduced in the last section to describe the motion of particles. -

Uniform Circular Motion

Uniform Circular Motion Part I. The Centripetal Impulse The “centripetal impulse” was Sir Isaac Newton’ favorite force. The Polygon Approximation. Newton made a business of analyzing the motion of bodies in circular orbits, or on any curved path, as motion on a polygon. Straight lines are easier to handle than circular arcs. The following pictures show how an inscribed or circumscribed polygon approximates a circular path. The approximation gets better as the number of sides of the polygon increases. To keep a body moving along a circular path at constant speed, a force of constant magnitude that is always directed toward the center of the circle must be applied to the body at all times. To keep the body moving on a polygon at constant speed, a sequence of impulses (quick hits), each directed toward the center, must be applied to the body only at those points on the path where there is a bend in the straight- line motion. The force Fc causing uniform circular motion and the force Fp causing uniform polygonal motion are both centripetal forces: “center seeking” forces that change the direction of the velocity but not its magnitude. A graph of the magnitudes of Fc and Fp as a function of time would look as follows: Force F p causing Polygon Motion Force Force F c causing Circular Motion time In essence, Fp is the “digital version ” of Fc . Imagine applying an “on-off force” to a ball rolling on the table − one hit every nanosecond – in a direction perpendicular to the motion. By moving around one billion small bends (polygon corners) per second, the ball will appear to move on perfect circle. -

Rotation: Moment of Inertia and Torque

Rotation: Moment of Inertia and Torque Every time we push a door open or tighten a bolt using a wrench, we apply a force that results in a rotational motion about a fixed axis. Through experience we learn that where the force is applied and how the force is applied is just as important as how much force is applied when we want to make something rotate. This tutorial discusses the dynamics of an object rotating about a fixed axis and introduces the concepts of torque and moment of inertia. These concepts allows us to get a better understanding of why pushing a door towards its hinges is not very a very effective way to make it open, why using a longer wrench makes it easier to loosen a tight bolt, etc. This module begins by looking at the kinetic energy of rotation and by defining a quantity known as the moment of inertia which is the rotational analog of mass. Then it proceeds to discuss the quantity called torque which is the rotational analog of force and is the physical quantity that is required to changed an object's state of rotational motion. Moment of Inertia Kinetic Energy of Rotation Consider a rigid object rotating about a fixed axis at a certain angular velocity. Since every particle in the object is moving, every particle has kinetic energy. To find the total kinetic energy related to the rotation of the body, the sum of the kinetic energy of every particle due to the rotational motion is taken. The total kinetic energy can be expressed as ..