Destination Shopping Defining “Destination” Retail in the New American Suburbs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sample First Page

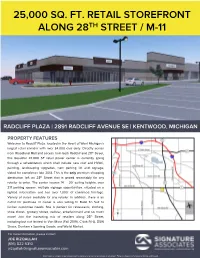

25,000 SQ. FT. RETAIL STOREFRONT ALONG 28TH STREET / M-11 RADCLIFF PLAZA | 2891 RADCLIFF AVENUE SE | KENTWOOD, MICHIGAN PROPERTY FEATURES Welcome to Radcliff Plaza, located in the Heart of West Michigan’s largest retail corridor with over 34,000 cars daily. Directly across from Woodland Mall and access from both Radcliff and 28th Street, this beautiful 47,000 SF retail power center is currently going through a rehabilitation which shall include new roof and HVAC, painting, landscaping upgrades, new parking lot and signage, slated for completion late 2018. This is the only premium shopping destination left on 28th Street that is priced reasonably for any retailer to enter. The center houses 14’ – 20’ ceiling heights, over 217 parking spaces, multiple signage opportunities, situated on a lighted intersection and has over 1,000’ of combined frontage. Variety of suites available for any retailer. In addition, there is an outlot for purchase or owner is also willing to Build To Suit to further customize needs. Site is perfect for restaurants, clothing, shoe stores, grocery stores, cellular, entertainment and so much more! Join the increasing mix of retailers along 28th Street, including but not limited to Von Mour (Fall 2019), Chick Fil-A, DSW Shoes, Dunham’s Sporting Goods, and World Market. For more information, please contact: JOE RIZQALLAH (616) 822 6310 [email protected] Information is subject to verification and no liability for errors or omissions is assumed. Price is subject to change and listing withdrawal. 2,162-25,185 2891 Radcliff Avenue SE – Kentwood, Michigan Square Feet Retail For Sale or Lease AVAILABLE Site Plan For more information, please contact: JOE RIZQALLAH SIGNATURE ASSOCIATES 1188 East Paris Ave SE, Suite 220 (616) 822 6310 Grand Rapids, MI 49546 [email protected] www.signatureassociates.com Information is subject to verification and no liability for errors or omissions is assumed. -

The BG News February 25, 2005

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-25-2005 The BG News February 25, 2005 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 25, 2005" (2005). BG News (Student Newspaper). 7406. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/7406 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. State University FRIDAY February 25, 2005 OSCAR NIGHTS The 77th Annual Academy PM SHOWERS Awards will announce HIGH: 33 LOW 20 winners; PAGE 8 www.bgnews.com independent student press VOLUME 99 ISSUE 121 USG: cheating policy unfair Students accused of time the unidentified stu- ^«%^M H\ - \~ r3 ui! dent involved in this case was cheating need more accused of cheating, he is being dismissed from BGSU for two •mt ^ ^»'—' -^ ^LM0V"ll"HB>MIB*m rights, USG says ■-—** years — unfairly, according to Malkin. By Bridget Triarp REPORTER Malkin said this student's work was taken by classmates USG passed a series of reso- and turned in to his instructor lutions this week that defend without his consent. the rights of students who are "Intent is not a defense," accused of cheating under the Malkin said. "You can't say I University academic honesty policy. didn't intend for it to get stolen — that's not a defense. -

City Commission Agenda Materials

City of East Grand Rapids YouTube Livestream: Regular City Commission Meeting https://bit.ly/2xXlLvn Agenda Begins at 6 pm. June 21, 2021 – 6:00 p.m. (EGR Community Center – 750 Lakeside Drive) Citizens may attend the meeting in person or virtually. 1. Call to Order. Virtual attendance/ participation information: 2. Approval of Agenda. https://www.eastgr.org/CivicAlerts.aspx?AID=781 3. Public Comment. 4. Report of Mayor, City Commissioners and City Manager. Regular Agenda Items 5. Zoning variance hearing on the request of Mark Gurney & Mary Yurko of 910 Rosewood to allow the enlargement of an accessory building to 1,180 sq. feet instead of the 720 sq. feet allowed (public hearing required; action requested). 6. Parks Improvement Debt Millage (public comment invited; action requested). a. Joint Resolution with East Grand Rapids Schools Regarding Playground Equipment Replacement. b. Resolution Authorizing Ballot Proposal for Park Improvement Bonds. 7. Advisory Board appointments for FY 2021-22 (no hearing required; approval requested). 8. Determination of annual required contribution and funding plan for Defined Benefit Plan (no hearing required; action requested). 9. Contract for reconfiguration of the Lakeside/Lakeside/Greenwood intersection (no hearing required; approval requested). 10. Purchase of wetlands mitigation credits (no hearing required; approval requested). 11. Contract for legal representation services (no hearing required; approval requested). 12. Discussion of work session date for Chapter 79C: Marijuana Establishments and Facilities (no hearing required; action requested). 13. Discussion of ordinance change to establish a separate Zoning Board of Appeals Facilities (no hearing required; action requested). Consent Agenda Items (no hearing required; approval requested unless noted). -

Michael Kors® Make Your Move at Sunglass Hut®

Michael Kors® Make Your Move at Sunglass Hut® Official Rules NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE OR PAYMENT WILL NOT INCREASE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED BY LAW OR REGULATION and outside the fifty United States (and the District of ColuMbia). Subject to all federal, state, and local laws, regulations, and ordinances. This Gift ProMotion (“Gift Promotion”) is open only to residents of the fifty (50) United States and the District of ColuMbia ("U.S.") who are at least eighteen (18) years old at the tiMe of entry (each who enters, an “Entrant”). 1. GIFT PROMOTION TIMING: Michael Kors® Make Your Move at Sunglass Hut® Gift Promotion (the “Gift ProMotion”) begins on Friday, March 22, 2019 at 12:01 a.m. Eastern Time (“ET”) and ends at 11:59:59 p.m. ET on Wednesday, April 3, 2019 (the “Gift Period”). Participation in the Gift Promotion does not constitute entry into any other promotion, contest or game. By participating in the Gift Promotion, each Entrant unconditionally accepts and agrees to comply with and abide by these Official Rules and the decisions of Luxottica of America Inc., 4000 Luxottica Place, Mason, OH 45040 d/b/a Sunglass Hut (the “Sponsor”) and WYNG, 360 Park Avenue S., 20th Floor, NY, NY 10010 (the “AdMinistrator”), whose decisions shall be final and legally binding in all respects. 2. ELIGIBILITY: Employees, officers, and directors of Sponsor, Administrator, and each of their respective directors, officers, shareholders, and employees, affiliates, subsidiaries, distributors, -

Portage Retail Market Analysis Gibbs Planning Group, Inc

Retail Market Analysis City of Portage, Michigan April 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 1 Background .......................................................................................................................... 2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................ 3 RETAIL TRADE AREAS ................................................................................................... 4 Primary Trade Area .............................................................................................................. 4 Secondary Trade Area .......................................................................................................... 6 Lifestyle Tapestry Demographics ........................................................................................ 7 Employment Base ................................................................................................................ 11 PORTAGE AREA CHARACTERISTICS .......................................................................... 14 Location ............................................................................................................................... 14 General Retail Market Conditions ...................................................................................... -

Q207 Supplemental 073107 Final

Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust Supplemental Financial and Operating Information Quarter Ended June 30, 2007 www.preit.com NYSE: (PEI) Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust Supplemental Financial and Operating Information June 30, 2007 Table of Contents Introduction Company Information 1 Press Release Announcements 2 Market Capitalization and Capital Resources 3 Operating Results Income Statement-Proportionate Consolidation Method - Three Months Ended June 30, 2007 and 2006 4 Income Statement-Proportionate Consolidation Method - Six Months Ended June 30, 2007 and 2006 5 Net Operating Income - Three Months Ended June 30, 2007 and 2006 6 Net Operating Income - Six Months Ended June 30, 2007 and 2006 7 Computation of Earnings per Share 8 Funds From Operations and Funds Available for Distribution 9 Operating Statistics Leasing Activity Summary 10 Summarized Rent Per Square Foot and Occupancy Percentages 11 Mall Sales and Rents Per Square Foot 12 Mall Occupancy - Owned GLA 13 Power Center and Strip Center Rents Per Square Foot and Occupancy Percentages 14 Top Twenty Tenants 15 Lease Expirations 16 Gross Leasable Area Summary 17 Property Information 18 Balance Sheet Balance Sheet - Proportionate Consolidation Method 21 Balance Sheet - Property Type 22 Investment in Real Estate 23 Property Redevelopment and Repositioning Summary 25 Development Property Summary 26 Capital Expenditures 27 Debt Analysis 28 Debt Schedule 29 Shareholder Information 30 Definitions 31 FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS This Quarterly Supplemental Financial and Operating Information contains certain “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of the U.S. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933 and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. -

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 Gamestop Dimond Center 80

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 GameStop Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard #3-118 Anchorage AK 99515 665 1703 (907) 272-7341 GameStop Anchorage 5th Ave. Mall 320 W. 5th Ave, Suite 172 Anchorage AK 99501 665 6139 (907) 332-0000 GameStop Tikahtnu Commons 11118 N. Muldoon Rd. ste. 165 Anchorage AK 99504 665 6803 (907) 868-1688 GameStop Elmendorf AFB 5800 Westover Dr. Elmendorf AK 99506 75 1833 (907) 474-4550 GameStop Bentley Mall 32 College Rd. Fairbanks AK 99701 665 3219 (907) 456-5700 GameStop & Movies, Too Fairbanks Center 419 Merhar Avenue Suite A Fairbanks AK 99701 665 6140 (907) 357-5775 GameStop Cottonwood Creek Place 1867 E. George Parks Hwy Wasilla AK 99654 665 5601 (205) 621-3131 GameStop Colonial Promenade Alabaster 300 Colonial Prom Pkwy, #3100 Alabaster AL 35007 701 3915 (256) 233-3167 GameStop French Farm Pavillions 229 French Farm Blvd. Unit M Athens AL 35611 705 2989 (256) 538-2397 GameStop Attalia Plaza 977 Gilbert Ferry Rd. SE Attalla AL 35954 705 4115 (334) 887-0333 GameStop Colonial University Village 1627-28a Opelika Rd Auburn AL 36830 707 3917 (205) 425-4985 GameStop Colonial Promenade Tannehill 4933 Promenade Parkway, Suite 147 Bessemer AL 35022 701 1595 (205) 661-6010 GameStop Trussville S/C 5964 Chalkville Mountain Rd Birmingham AL 35235 700 3431 (205) 836-4717 GameStop Roebuck Center 9256 Parkway East, Suite C Birmingham AL 35206 700 3534 (205) 788-4035 GameStop & Movies, Too Five Pointes West S/C 2239 Bessemer Rd., Suite 14 Birmingham AL 35208 700 3693 (205) 957-2600 GameStop The Shops at Eastwood 1632 Montclair Blvd. -

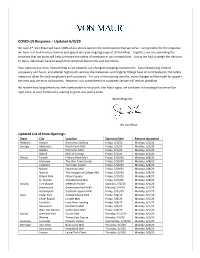

COVID-19 Response – Updated 6/3/20 on June 4Th, Von Maur Will Have 100% of Our Stores Open in the Communities That We Serve

COVID-19 Response – Updated 6/3/20 On June 4th, Von Maur will have 100% of our stores open in the communities that we serve. I am grateful for the response we have received from customers and appreciate your ongoing support of Von Maur. Together, we are upholding the practices that we know will help to ensure the safety of everyone in our communities. Just as we had to weigh the decision to open, individuals have to weigh their personal decision to visit our stores. Your patience has been instrumental as we adapt to our changed shopping environment. Social distancing, limited occupancy and hours, and altered high touch services like makeovers and lingerie fittings have all contributed to the safety measures taken for both employees and customers. I’m sure in the coming months, more changes will be made to support the new way we must do business. However, our commitment to customer service will remain steadfast. No matter how long before you feel comfortable to shop with Von Maur again, be confident in knowing that we will be right here, in your community, waiting to greet you with a smile. Warm Regards, Jim von Maur Updated List of Store Openings: State City Location Opening Date Returns Accepted Alabama Hoover Riverchase Galleria Friday, 5/1/20 Monday, 6/1/20 Georgia Alpharetta North Point Mall Friday, 5/1/20 Monday, 6/1/20 Atlanta Perimeter Mall Friday, 5/1/20 Monday, 6/1/20 Buford Mall of Georgia Friday, 5/1/20 Monday, 6/1/20 Illinois Forsyth Hickory Point Mall Friday, 5/29/20 Monday, 6/8/20 Glenview The Glen Town Center Friday, 5/29/20 Monday, 6/8/20 Lombard Yorktown Center Friday, 5/29/20 Monday, 6/8/20 Moline SouthPark Mall Friday, 5/29/20 Monday, 6/8/20 Normal The Shoppes at College Hills Friday, 5/29/20 Monday, 6/8/20 Orland Park Orland Square Friday, 5/29/20 Monday, 6/8/20 St. -

PREIT's Woodland Mall to Relaunch Movie Theatre with Phoenix Theatres

PREIT’s Woodland Mall to Relaunch Movie Theatre with Phoenix Theatres Michigan-Based Company’s Investment to Bring Back First-Run Films with First-Class Amenities Highlights Appeal of Redeveloped Woodland Mall PHILADELPHIA, July 27, 2021 – PREIT (NYSE: PEI), a leading real estate owner and developer, redefining the future of the mall with mixed-use community-centric districts, today announced that Phoenix Theatres has signed a lease to bring first-run movies back to Woodland Mall, including West Michigan’s first theatre with Dolby Atmos® sound. This is the first location in West Michigan for Phoenix Theatres, which expects to welcome moviegoers in late 2021. The 21-year-old independently owned movie theatre company plans to invest $4 million to refurbish the 14-screen theatre, creating a new premiere movie-going experience in the greater Grand Rapids- area. Renovation plans include all-new premium reclining heated seating, 4K digital projection with Dolby Atmos, first-run movies, and family-friendly pricing. Phoenix Theatres at Woodland Mall is the first major post-pandemic theatre investment in West Michigan – and one of the first in the country, signaling confidence in the strength of the property and the regional economy. This addition furthers PREIT’s strategic efforts to attract innovative tenants and redefine the Company’s high barrier-to-entry portfolio with a unique mix of uses that serves its communities. Phoenix Theatres joins other top-tier experiences from The Cheesecake Factory and Black Rock Bar & Grill and a tremendous existing retail lineup which includes: Sephora, Lush, Williams-Sonoma, Pottery Barn, Von Maur, Urban Outfitters, Altar’d State and Apple. -

Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust ®

Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust ® Supplemental Financial and Operating Information Quarter Ended March 31, 2011 www.preit.com NYSE: PEI Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust Supplemental Financial and Operating Information March 31, 2011 Table of Contents Introduction Company Information 1 Press Release Announcements 2 Market Capitalization and Capital Resources 3 Operating Results Statement of Operations - Proportionate Consolidation Method - Quarters Ended March 31, 2011 and March 31, 2010 4 Net Operating Income - Quarters Ended March 31, 2011 and March 31, 2010 5 Computation of Earnings Per Share 6 Funds From Operations and Funds Available for Distribution - Quarters Ended March 31, 2011 and March 31, 2010 7 Operating Statistics Leasing Activity Summary 8 Summarized Rent Per Square Foot and Occupancy Percentages 9 Mall Sales and Rent Per Square Foot 10 Enclosed Mall Occupancy - Owned GLA 11 Strip and Power Center Rent Per Square Foot and Occupancy Percentages 12 Top Twenty Tenants 13 Lease Expirations 14 Gross Leasable Area Occupancy Summary 15 Property Information 16 Balance Sheet Balance Sheet - Proportionate Consolidation Method 19 Balance Sheet - Property Type 20 Investment in Real Estate 21 Capital Expenditures 23 Debt Analysis 24 Debt Schedule 25 Selected Debt Ratios 26 Shareholder Information 27 Definitions 28 FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS This Quarterly Supplemental and Operating Information contains certain “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of the U.S. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933 and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Forward-looking statements relate to expectations, beliefs, projections, future plans, strategies, anticipated events, trends and other matters that are not historical facts. -

Meeting Packet BOARD of TRUSTEES NOVEMBER 2019

BOARD OF TRUSTEES Meeting Packet 11 NOVEMBER 2019 1 DRAFT BOARD OF TRUSTEES Meeting Agenda LOCATION KDL Wyoming Branch (3350 Michael Ave SW, Wyoming, MI 49509) DATE + TIME Thursday, November 21, 2019 at 7:00 p.m. 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE 3. CONSENT AGENDA* A. Approval of Agenda B. Approval of Minutes: October 10, 2019 (Open and Closed Sessions), October 24, 2019 4. LIAISON REPRESENTATIVE COMMENTS 5. PUBLIC COMMENTS** 6. PUBLIC HEARING – 2020 Budget Roll Call Vote 7. FINANCE REPORTS - October 2019* 8. BRANCH MANAGER’S REPORT – Anjie Gleisner 9. LAKELAND LIBRARY COOPERATIVE REPORT 10. DIRECTOR’S REPORT – October 2019 11. NEW BUSINESS A. Strategic Plan Update B. Director’s Evaluation: Request for December Closed Session* C. Resolution: Second 2019 Budget Amendment* Roll Call Vote D. Resolution: Approval of 2020 Budget * Roll Call Vote E. “Behind the Scenes at KDL” Video Presentation 12. LIAISON REPRESENTATIVE COMMENTS 13. PUBLIC COMMENTS** 14. BOARD MEMBER COMMENTS 15. MEETING DATES Next Regular Meeting: Thursday, December 19, 2019 – KDL Service + Meeting Center, 4:30 PM 16. ADJOURNMENT * Requires Action ** According to Kent District Library Board of Trustee Bylaws, Article VII, Item 7.1.3, “Public comments will be limited to 3 minutes per person or group and 15 minutes per subject.” DRAFT BOARD OF TRUSTEES MEETING MINUTES LOCATION KDL Meeting Center (814 West River Center Dr., Comstock Park, MI 49321) DATE Thursday, October 10, 2019 at 4:30 p.m. BOARD PRESENT: Shirley Bruursema, Andrew Erlewein, Sheri Gilreath-Watts, Allie Bush Idema, Charles Myers, Caitie S. Oliver, Penny Weller BOARD ABSENT: Tom Noreen STAFF PRESENT: Jaci Cooper, Lindsey Dorfman, Randy Goble, Brian Mortimore, Jared Olson, Laura Powers, Lance Werner, Carrie Wilson GUESTS PRESENT: None. -

Store Listing

APPENDIX C STORE LISTING All shipments must be shipped to the Dry Goods Distribution Center at with the specific store number indicated on the Shipping Label, Carton, and Packing Slip. Do not ship directly to the store. DRY GOODS - Distribution Center 6565 Brady Street Davenport, IA 52806 Store # Initials Store Name/Location Store # Initials Store Name/Location 1001 FXVY Fox Valley/Aurora, IL 1040* SLIN Southlake Mall/Merrilville, IN 1002 WFLD Woodfield Mall/Schaumburg, IL 1041* PCMI Partridge Creek/Clinton Township, MI 1003 WSTN West Towne/Madison, WI 1042* DPIL Deer Park Town Center/Deer Park, IL 1004 MYFR Mayfair Mall/Milwaukee, WI 1043* OPKS Oak Park Mall/Overland Park, KS 1005 TWOK Twelve Oaks Mall/Detroit, MI 1044* EWMI Eastwood Towne Center/Lansing, MI 1006 RSDL Rosedale Mall/Roseville, MN 1045* NLNC Northlake Mall/Charlotte, NC 1007 ORSQ Orland Square/Orland Park, IL 1046* LJIL Louis Joliet Mall/Joliet, IL 1008 JDCR Jordan Creek Mall/West Des Moines, IA 1047** SPOH SouthPark Mall/Strongsville, OH 1009 STDL Southdale Center/Edina, MN 1048** BPOH Beachwood Place/Beachwood, OH 1010 CRIA Coralridge Mall/Coralville, IA 1049** CVNC Crabtree Valley Mall/Raleigh, NC 1011 HWIL Westfield Hawthorn/Vernon Hills, IL 1050** CSTN CoolSprings Galleria/Franklin, TN 1012 APMN Apache Mall/Rochester, MN 1051** GHTN Mall at Green Hills/Nashville, TN 1013 FMIN Fashion Mall/Indianapolis, IN 1052** FPOH Franklin Park Mall/Toledo, OH 1014 CRMN Crossroads Center/St. Cloud, MN 1053** GWNE Gateway Mall/Lincoln, NE 1015 RDMN Ridgedale Center/Minnetonka, MN