Also Suggest a Relatively High Level of Concern About the Issue, with Between 60% and 76% Characterizing It As a “Major Proble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aries (Sun Sign Series)

ARIES Sun Sign Series ALSO BY JOANNA MARTINE WOOLFOLK Sexual Astrology Honeymoon for Life The Only Astrology Book You’ll Ever Need ARIES Sun Sign Series JOANNA MARTINE WOOLFOLK Taylor Trade Publishing Lanham • New York • Boulder • Toronto • Plymouth, UK Published by Taylor Trade Publishing An imprint of The Rowma n & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rlpgtrade.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Distributed by National Book Network Copyright © 2011 by Joanna Martine Woolfolk All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Woolfolk, Joanna Martine. Aries / Joanna Martine Woolfolk. p. cm.—(Sun sign series) ISBN 978-1-58979-553-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-1-58979-528-0 (electronic) 1. Aries (Astrology) I. Title. BF1727.W66 2011 133.5’262—dc22 2011001964 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America I dedicate this book to the memory of William Woolfolk whose wisdom continues to guide me, and to James Sgandurra who made everything bloom again. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Astrologer Joanna Martine Woolfolk has had a long career as an author, columnist, lecturer, and counselor. -

Clergy Sexual Abuse: Annotated Bibliography of Conceptual and Practical Resources

Clergy Sexual Abuse: Annotated Bibliography of Conceptual and Practical Resources. Preface The phenomenon of sexual abuse as committed by persons in fiduciary relationships is widespread among helping professions and is international in scope. This bibliography is oriented to several specific contexts in which that phenomenon occurs. The first context is the religious community, specifically Christian churches, and particularly in the U.S. This is the context of occurrence that I best know and understand. The second context for the phenomenon is the professional role of clergy, a religious vocation and culture of which I am a part. While the preponderance of sources cited in this bibliography reflect those two settings, the intent is to be as comprehensive as possible about sexual boundary violations within the religious community. Many of the books included in this bibliography were obtained through interlibrary loan services that are available at both U.S. public and academic libraries. Many of the articles that are listed were obtained through academic libraries. Daily newspaper media sources are generally excluded from this bibliography for practical reasons due to the large quantity, lack of access, and concerns about accuracy and completeness. In most instances, author descriptions and affiliations refer to status at time of publication. In the absence of a subject or name index for this bibliography, the Internet user may trace key words in this PDF format through the standard find or search feature that is available as a pull-down menu option on the user’s computer. The availability of this document on the Internet is provided by AdvocateWeb, a nonprofit corporation that serves an international community and performs an exceptional service for those who care about this topic. -

Morrie Gelman Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8959p15 No online items Morrie Gelman papers, ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Finding aid prepared by Jennie Myers, Sarah Sherman, and Norma Vega with assistance from Julie Graham, 2005-2006; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2016 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Morrie Gelman papers, ca. PASC 292 1 1970s-ca. 1996 Title: Morrie Gelman papers Collection number: PASC 292 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 80.0 linear ft.(173 boxes and 2 flat boxes ) Date (inclusive): ca. 1970s-ca. 1996 Abstract: Morrie Gelman worked as a reporter and editor for over 40 years for companies including the Brooklyn Eagle, New York Post, Newsday, Broadcasting (now Broadcasting & Cable) magazine, Madison Avenue, Advertising Age, Electronic Media (now TV Week), and Daily Variety. The collection consists of writings, research files, and promotional and publicity material related to Gelman's career. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Creator: Gelman, Morrie Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

Mary in Film

PONT~CALFACULTYOFTHEOLOGY "MARIANUM" INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE (UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON) MARY IN FILM AN ANALYSIS OF CINEMATIC PRESENTATIONS OF THE VIRGIN MARY FROM 1897- 1999: A THEOLOGICAL APPRAISAL OF A SOCIO-CULTURAL REALITY A thesis submitted to The International Marian Research Institute In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Licentiate of Sacred Theology (with Specialization in Mariology) By: Michael P. Durley Director: Rev. Johann G. Roten, S.M. IMRI Dayton, Ohio (USA) 45469-1390 2000 Table of Contents I) Purpose and Method 4-7 ll) Review of Literature on 'Mary in Film'- Stlltus Quaestionis 8-25 lli) Catholic Teaching on the Instruments of Social Communication Overview 26-28 Vigilanti Cura (1936) 29-32 Miranda Prorsus (1957) 33-35 Inter Miri.fica (1963) 36-40 Communio et Progressio (1971) 41-48 Aetatis Novae (1992) 49-52 Summary 53-54 IV) General Review of Trends in Film History and Mary's Place Therein Introduction 55-56 Actuality Films (1895-1915) 57 Early 'Life of Christ' films (1898-1929) 58-61 Melodramas (1910-1930) 62-64 Fantasy Epics and the Golden Age ofHollywood (1930-1950) 65-67 Realistic Movements (1946-1959) 68-70 Various 'New Waves' (1959-1990) 71-75 Religious and Marian Revival (1985-Present) 76-78 V) Thematic Survey of Mary in Films Classification Criteria 79-84 Lectures 85-92 Filmographies of Marian Lectures Catechetical 93-94 Apparitions 95 Miscellaneous 96 Documentaries 97-106 Filmographies of Marian Documentaries Marian Art 107-108 Apparitions 109-112 Miscellaneous 113-115 Dramas -

Arguments Against Lesbian and Gay Parenting

Women’s Studies International Forum, Vol. 24, No. 5, pp. 555–570, 2001 Copyright © 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd Pergamon Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0277-5395/01/$–see front matter PII S0277-5395(01)00193-5 WHAT ABOUT THE CHILDREN? ARGUMENTS AGAINST LESBIAN AND GAY PARENTING Victoria Clarke Loughborough University, Women’s Studies Research Group, Department of Social Sciences, Loughborough, Leicestershire LE 113TU, UK Synopsis — In this article, I explore arguments commonly used to support the claim that lesbians and gay men should not be parents. Thematic analysis of recent media representations of lesbian and gay parenting and six focus groups with university students highlighted the repeated use of a number of ar- guments to oppose lesbian and gay parenting. I critically discuss the six most prevalent in this article. These are: (1) “The bible tells me that lesbian and gay parenting is a sin”; (2) “Lesbian and gay parent- ing is unnatural”; (3) “Lesbian and gay parents are selfish because they ignore ‘the best interests of the child’”; (4) “Children in lesbian and gay families lack appropriate role models”; (5) Children in lesbian and gay families grow up lesbian and gay; and (6) “Children in lesbian and gay families get bullied.” I examine these themes in relation to other debates about lesbian and gay and women’s rights, and high- light the ways in which they reinforce a heterosexual norm. © 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights re- served. INTRODUCTION from feminist research and theorising on mar- ginal parenting in this paper, by focusing on Feminist research has noted that while moth- the construction of lesbians and gay men as in- erhood is socially constructed as fulfilling and appropriate parents. -

Clohessy, David January 2, 2012.Exe

A50A471 DAVID CLOHESSY JANUARY 2, 2012 1 IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF JACKSON COUNTY STATE OF MISSOURI 2 CASE NO. 1016-CV-29995 3 4 JOHN DOE, B. P. 5 Plaintiff 6 vs. 7 FATHER MICHAEL TIERNEY, et al. 8 Defendants 9 _________________________________________/ 10 11 12 Crowne Plaza Hotel 7750 Carondelet Avenue 13 Clayton, Missouri January 2, 2012 14 9:00 A.M. to 4:00 P.M. 15 16 VIDEOTAPED_DEPOSITION_OF_DAVID_CLOHESSY __________ __________ __ _____ ________ 17 18 19 20 Taken before Sandra L. Ragsdale, Certified 21 Court Reporter by the State of Missouri, pursuant to Notice for: 22 23 Atkinson-Baker, Inc. Court Reporters 500 North Brand Boulevard, Third Floor 24 Glendale, California 91203 800-288-3376, www.depo.com 25 File A50A471 Page 1 ATKINSON-BAKER, INC. 1-800-288-3376 A50A471 DAVID CLOHESSY JANUARY 2, 2012 1 A_P_P_E_A_R_A_N_C_E_S 1 INDEX_TO_TESTIMONY _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _____ __ _________ 2 2 Page 3 Jeffrey B. Jensen, Esq. 3 Examination by Mr. Madden.......................8 Matthew P. Diehr, Esq. Examination by Mr. Wyrsch......................66 4 Jensen Bartlett & Schelp, LLC 4 Luncheon recess...............................104 222 S. Central Avenue, Suite 110 Examination by Mr. Wyrsch.....................104 5 St. Louis, Missouri 63105 5 Examination by Ms. Cohara.....................146 314-725-3939 Examination by Mr. Meyers.....................181 6 [email protected] 6 Examination by Mr. McGonagle..................190 7 On behalf of David Clohessy Examination by Mr. Jensen.....................211 8 7 Rebecca M. Randles, Esq. 8 INDEX_TO_EXHIBITS 9 Randles Mata & Brown, LLC _____ __ ________ 406 West 34th Street, Suite 623 9 10 Kansas City, Missouri 64111 Exhibit 1.......................................15 816-931-9901 11 [email protected] 10 Tax return 2010 12 On behalf of plaintiffs John Doe, B.P., 11 Exhibit 2.......................................40 John Doe, J.D., John Doe, M.F., Joe Eldred, Subpoena to David Clohessy 13 John Doe, M.S., Jane Doe, I.P. -

January/February 2011 FFRF Blasts Army ‘Spiritual Fitness’ Survey

Freethought Complimentary Copy Today Join FFRF Now! Vol. 28 No. 1 Published by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Inc. January/February 2011 FFRF blasts Army ‘spiritual fitness’ survey In a Dec. 29 complaint to Secretary “I believe there is a purpose for my life.” of the Army John McHugh, the Free- “I often find comfort in my religion or dom From Religion Foundation said spiritual beliefs.” the U.S. Army has no business sub- “In difficult times, I pray or meditate.” jecting military troops to a mandatory “I attended religious services [how often “spiritual fitness” assessment. FFRF, the last month].” which has many members who are Barker and Gaylor called the nega- “foxhole atheists,” asked the Army to tive assessment for nonspiritual sol- immediately stop the evaluation that’s diers deeply offensive and inappro- part of a program called Comprehen- priate. “By definition, nontheists do sive Soldier Fitness. not believe in deities, spirits or the “It is ironic that while nonbelievers supernatural. The Army may not send are fighting to protect freedoms for all the morale-deflating message to non- Americans, their freedoms are being believers that they are lesser soldiers, trampled upon by this Army practice,” much less imply they are somehow wrote Foundation Co-Presidents Dan incomplete, purposeless or empty. Barker and Annie Laurie Gaylor. As nontheists, we reject the idea that The letter noted that while about there is a purpose for life; we believe 15% of the U.S. population is not re- individuals make their own purpose in ligious, surveys have shown that close life.” to one-fourth of all military personnel Those who receive low “spiritual fit- identify as atheist, agnostic or have no ness” ratings are referred to a training religious preference. -

Scandal Time by Richard John Neuhaus

1 Scandal Time by Richard John Neuhaus Copyright (c) 2002 First Things (April 2002). The Public Square The timing, it seems, could not have been worse. In last month’s issue I offered my considered and heartfelt defense of Father Maciel, founder of the Legionaries of Christ, against unfounded charges of sexual abuse. I meant and I mean every word of what I said there. Just after the issue had gone to press, however, scandals involving sexual abuse by priests in Boston exploded, creating a level of public outrage and suspicion that may be unparalleled in recent history. The climate is not conducive to calm or careful thought about priests and sexual molestation. Outrage and suspicion readily lead to excess, but, with respect to developments in Boston, it is not easy to say how much outrage and suspicion is too much. Professor Philip Jenkins of Penn State University has written extensively on sexual abuse by priests, also in these pages (see “The Uses of Clerical Scandal,” February 1996). He is an acute student of the ways in which the media, lawyers, and insurance companies-along with angry Catholics, both liberal and conservative-are practiced at exploiting scandal in the service of their several interests. Scholars point out that the incidence of abusing children or minors is no greater, and may be less, among priests than among Protestant clergy, teachers, social workers, and similar professions. But, it is noted, Catholic clergy are more attractive targets for lawsuits because the entire diocese or archdiocese can be sued. That is a legal liability of the Church’s hierarchical structure. -

Not Yet Retained

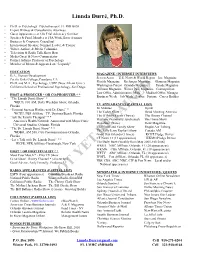

Linnda Durré, Ph.D. • Ph.D. in Psychology–Psychotherapist, FL #MH6058 • Expert Witness & Consultant to Attorneys • Guest Appearances at FJA Trial Advocacy Seminar • Speaker & Panel Member at FJA Work Horse Seminar • Business & Corporate Consultant • International Speaker, Seminar Leader, & Trainer • Writer, Author, & Media Columnist • Television & Radio Talk Show Host • Media Guest & News Commentator • Former Adjunct Professor of Psychology • Member of Mensa & Appeared on “Jeopardy” EDUCATION MAGAZINE / INTERNET INTERVIEWS • B.A., Human Development Screen Actor U.S. News & World Report Inc. Magazine Pacific Oaks College, Pasadena, CA Florida Magazine Recharger Magazine Glamour Magazine • Ph.D. and M.A., Psychology, CSPP (Now Alliant Univ.) Washington Parent Orlando Magazine Parade Magazine California School of Professional Psychology, San Diego Affluent Magazine Winter Park Magazine Cosmopolitan Law Office Administrator More Medical Office Manager HOST & PRODUCER * OR CO-PRODUCER * * Business Week Job Week Forbes Fortune Career Builder • “The Linnda Durré Show” * WEUS, 810 AM, Daily Weekday Show, Orlando, TV APPEARANCES (PARTIAL LIST) Florida 60 Minutes Oprah • “Personal Success Hotline with Dr. Durré” * The Today Show Good Morning America WCEU, PBS Affiliate –TV, Daytona Beach, Florida The O’Reilly Factor (Twice) The Disney Channel • “Ask the Family Therapist” * * Daytime (Nationally syndicated) The Home Show America’s Health Network–Associated with Mayo Clinic Donahue (Twice) Hour Magazine Universal Studios, Orlando, Florida The Home and Family Show People Are Talking • “The Dr. Linnda Durré Show” * * The Sally Jessy Raphael Show Canada AM WDBO, AM 580, Cox Communications-Orlando, Good Day Orlando (3 times) KCET Pledge Drives Florida CF RETAINEDNews 13 (11 appearances) WKMG Pledge Drives • “Let’s Talk with Dr. -

Strategies of Apologia Used by the Roman Catholic Church In

“FATHER FORGIVE ME FOR I HAVE SINNED”: STRATEGIES OF APOLOGIA USED BY THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH IN ADDRESSING THE SEXUAL ABUSE CRISIS A Thesis by CHERYL ELAINE LOZANO-WHITTEN Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2010 Major Subject: Communication “Father Forgive Me For I Have Sinned”: Strategies of Apologia Used by the Roman Catholic Church in Addressing the Sexual Abuse Crisis Copyright 2010 Cheryl Elaine Lozano-Whitten “FATHER FORGIVE ME FOR I HAVE SINNED”: STRATEGIES OF APOLOGIA USED BY THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH IN ADDRESSING THE SEXUAL ABUSE CRISIS A Thesis by CHERYL ELAINE LOZANO-WHITTEN Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, James Aune Committee Members, Charles Conrad Robert Mackin Head of Department, Richard Street May 2010 Major Subject: Communication iii ABSTRACT “Father Forgive Me for I Have Sinned”: Strategies of Apologia Used by the Roman Catholic Church in Addressing the Sexual Abuse Crisis. (May 2010) Cheryl Elaine Lozano-Whitten, B.A., Saint Edward’s University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. James Arnt Aune The sexual abuse by Roman Catholic clergy has overwhelmed public media and has resulted in a barrage of criminal and civil lawsuits. Between October of 1985 and November of 2002, more than three-hundred and ninety-four media sources reported on allegations of sexual misconduct worldwide. The response by the hierarchy of the church has been defensive with little effort in expressing remorse. -

CARRI E CARM ICHAEL [email protected]

CARRI E CARM ICHAEL [email protected] AEA/SAG/ AFTRA Actor/Singer/Comedian 212-799-8977/917 -579-6902 Voice Overt Radio/Writer Theater: "You Never Know" - one person show "Shoot The Messenger" with Lizz Winstead, "Extreme Foreclosure," Design Your Kitchen Bat Co'/Flea Theatre - Dave Feingold's grandmother - Jim Simpson, dir. Hot Flashes-LaLuna Productions - Elise, Women of Manhattan-Liberty Players - Rhonda Hot I Baltimore Portal Theatre Co. - Mrs. Bellotti Beggars In The House Of Plenty Bad Dog Rep. - Ma Pirates of Penzance Light Opera of Manhattan - Edith Television: "Hollywood Stars"- celebrityinterviews, The Guiding Light - Katie, the nanny As The World Turns, $10,000 Pyramid winner, Jeopardy, Good Day NY/Fox TV, Sally Jessy Raphael Show, Medical News Network, News of New York, Women: NY Edition on WNYC-TV Feature .iI.: HEARTTOHEART.COM - Rosanna Standup COMedy: 55 Grove Street, Upstairs at Rose's Turn, Caroline'S, Stand-Up NY, West End Gate, Comic Strip, ITHudson's, Schoolhouse Theatre Author of bootEs: Non-Sexist Chlldralslng, Beacon Press Old-Fashioned Babycare, Prentice Hall How To Relieve Cramps and Other Menstrual Problems, with Marcia L.Storch, MD, Workman Press Secrets of the Great Magicians - Raintree Press; Bigfoot Man, Monster or Myth? - Raintree Press Author of naagazine and newspaper artides: New York Times Magazine -"LlVES" column, New York Times Book Review, New York Post, Newsday, Family Circle, Child, Family Weekly, UPI, Gannett papers and the Esquire, Mikihouse and Staste magazines of Japan Playwright: "You -

Canon Law and the Response of the Roman Catholic Church to the Sex Abuse Scandals

Washington University Global Studies Law Review Volume 4 Issue 1 January 2005 Dark Days for the Church: Canon Law and the Response of the Roman Catholic Church to the Sex Abuse Scandals Kathleen R. Robertson Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Kathleen R. Robertson, Dark Days for the Church: Canon Law and the Response of the Roman Catholic Church to the Sex Abuse Scandals, 4 WASH. U. GLOBAL STUD. L. REV. 161 (2005), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_globalstudies/vol4/iss1/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Global Studies Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DARK DAYS FOR THE CHURCH: CANON LAW AND THE RESPONSE OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH TO THE SEX ABUSE SCANDALS Within the past few years, a nearly global scandal has developed over allegations that priests and other religious personnel have sexually abused children.1 The scandals intensified when it became known that many in the Church hierarchy had not only covered up allegations, but also had reassigned abusers to work in different positions, often in contact with children. This scandal has stretched around the world, causing outrage and resulting in calls for reform by both members of the Church and the public. The Catholic Church has addressed the scandal in several ways, including settling lawsuits, removing those responsible for the cover-ups from positions of power, and creating policies to address the problem.2 However, the intent of the Church leaders to truly fix their mistakes has been questioned, as has the efficacy of the proposed solutions.