Transferring Memory: the Task of Children and Grandchildren of Holocaust Survivors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

October 29, 2020 Hon. Scott S. Harris Clerk of the Court Supreme Court Of

October 29, 2020 Hon. Scott S. Harris Clerk of the Court Supreme Court of the United States 1 First St. NE Washington, DC 20543 Re: No. 19-351, Federal Republic of Germany, et al. v. Philipp, et al. and No. 18-1447, Republic of Hungary, et al. v. Simon, et al. Dear Clerk Harris: In accordance with Rule 32(3) of the Rules of the Supreme Court of the United States, amici curiae the World Jewish Congress, Commission for Art Recovery, and Ambassador Ronald S. Lauder submit this proposal to lodge certain non-record materials with the Court. These cases concern in part whether takings that took place during the Nazi regimes in Germany and Hungary violated international law, such that Petitioners are not immune from suit in a U.S. court pursuant to the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1605(a)(3). Among the issues now briefed in both cases is the proper historical perspective from which those events and the applicable law should be viewed. In support of the brief filed with this Court by the undersigned amici curiae, Ambassador Lauder has prepared a brief statement, based upon his decades of commitment to representing the interests of Jews and Jewish communities throughout the world. His statement underscores the scale and devastation of the theft and expropriation utilized as part of the Nazis’ genocidal campaign in Europe and the connection between genocide and the takings, particularly with respect to art and cultural objects such as the collection of artifacts at issue in Philipp. Ambassador Lauder’s statement also provides information regarding the importance of the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act in developing U.S. -

Remarks on Proposed Education Appropriations Legislation and an Exchange with Reporters September 12, 2000

Administration of William J. Clinton, 2000 / Sept. 12 going to happen?’’ I say, ‘‘Well, I’m pretty opti- so much darkness since the dawn of human mistic.’’ The Speaker of the Knesset said, ‘‘Ah, history has not yet quite been expunged from yes, but that’s your nature. Everyone knows it.’’ the human soul. And so we all still have work [Laughter] The truth is, we have come to a to do. painful choice between continued confrontation Thank you, and God bless you. and a chance to move beyond violence to build just and lasting peace. Like all life’s chances, this one is fleeting, and the easy risks have all NOTE: The President spoke at 9:38 p.m. in the been taken already. Grand Ballroom at the Pierre Hotel. In his re- I think it important to remind ourselves that marks, he referred to Edgar Bronfman, Sr., presi- the Middle East brought forth the world’s three dent, World Jewish Congress, his son, Edgar great monotheistic religions, each telling us we Bronfman, Jr., president and chief executive offi- must recognize our common humanity; we must cer, Seagram and Sons, and his daughter-in-law, love our neighbor as ourselves; if we turn aside Clarissa Bronfman; Israel Singer, secretary gen- a stranger, it is as if we turn aside the Most eral, World Jewish Congress; Nobel Prize winner High God. and author Elie Wiesel; former Senator Alfonse But when the past is piled high with hurt M. D’Amato; Vice Chancellor Joschka Fischer and and hatred, that is a hard lesson to live by. -

Activities of the World Jewish Congress 1975 -1980

ACTIVITIES OF THE WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS 1975 -1980 REPORT TO THE SEVENTH PLENARY ASSEMBLY OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL GENEVA 5&0. 3 \N (i) Page I. INTRODUCTION . 1 II. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Israel and the Middle East 5 Action against Anti-Semitism. 15 Soviet Jewry. 21 Eastern Europe 28 International Tension and Peace..... 32 The Third World 35 Christian-Jewish Relations 37 Jewish Communities in Distress Iran 44 Syria 45 Ethiopia 46 WJC Action on the Arab Boycott 47 Terrorism 49 Prosecution of Nazi Criminals 52 Indemnification for Victims of Nazi Persecution 54 The WJC and the International Community United Nations 55 Human Rights 58 Racial Discrimination 62 International Humanitarian Law 64 Unesco 65 Other international activities of the WJC 68 Council of Europe.... 69 European Economic Community 72 Organization of American States 73 III. CULTURAL ACTIVITIES 75 IV. RESEARCH 83 (ii) Page V. ORGANIZATIONAL DEVELOPMENTS Central Organs and Global Developments Presidency 87 Executive 87 Governing Board 89 General Council.... 89 New Membership 90 Special Relationships 90 Relations with Other Organizations 91 Central Administration 92. Regional Developments North America 94 Caribbean 97 Latin America 98 Europe 100 Israel 103 South East Asia and the Far East 106 Youth 108 WJC OFFICEHOLDERS 111 WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS CONSTITUENTS 113 WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS OFFICES 117 I. INTRODUCTION The Seventh Plenary Assembly of the World Jewish Congress in Jerusalem, to which this Report of Activities is submitted, will take place in a climate of doubt, uncertainty, and change. At the beginning of the 80s our world is rife with deep conflicts. We are perhaps entering a most dangerous decade. -

R E P O R T of the World Jewish Congress Organization Department

REPORT of the World Jewish Congress Organization Department August 1951 ־ August 1949 by DR. I. SCHWARZBART WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS 15 East 84th Street New York 28, N. Y. 1951 CONTENTS msê. IN MEMORIAM DR. STEPHEN S. WISE AND LOUISE WATERMAN WISE INTRODUCTION 1 SECTION I A. THE CENTRAL BODIES OF TKE WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS (a) Composition of the Executive ............. 2 (b) Meetings of the Executive . 3 (c) General Council 3 (d) Plenary Assembly of the World Jewish Congress and. Constitution 4 B. THE ORGANIZATIONAL TASK OF TEE WORLD JEWISH CONGRESS ׳a) New Affiliations . 4) (b) Organizing Communities and strengthening existing Affiliations # 5 (c) Visits by our Emissaries. 7 C. CHANGES IN JEWISH LIFE AND WJC ORGANIZATIONAL TASKS (a) 3he Sephardic World reappears on the Stage of Jewish History 10 (b) Relations of the WJC with other Jewish Galuth Organizations ........... .... 11 (c) Relations between the WJC and the World Zionist Organizations 12 (d) Agreement with the Jewish Agency ........... 12 (e) The State of Israel 13 ־f) East and West 1*4) How the Organization Department works. ... The Commemoration of the 7th and 8th Anniversaries of the %rsaw Ghetto Uprising ........... 15 SECTION II - THE WORK OF THE ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT AND TEAT OF OUR AFFILIATES WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON TKE ORGANIZATIONAL FIELD A. GENERAL (a) The Executive Branches 16 (b) The. Offices of the World Jewish Congress 16 - i - IMS. B. INDIVIDUAL COUNTRIES Israel ............ » • 18 Western Hemis-phere United States of America ... ...... 19 Canada 21 Latin America - General Remarks « 23 Argentina ......... 24 Brazil 26 Uruguay . ...» 27 Chile 29 Mexico 30 ן • Cuba, Colombia .............. -

Remarks at the Partners in History Dinner in New York City September 11, 2000

Administration of William J. Clinton, 2000 / Sept. 11 Remarks at the Partners in History Dinner in New York City September 11, 2000 Thank you very much. Let me say, first of how many times she reminded me of her meet- all, Hillary and I are delighted to be here with ings with elderly survivors all around the world, all of you, and especially you, Edgar, with all and how many times she tried to shine a light of your family, including Edgar, Clarissa, and on the quest for material and moral justice. So the about-to-be 22d grandchild here. They are thank you for helping me be here tonight. probably an even more important testament to I would like to say again what I said before, your life than this important work we celebrate Senator D’Amato and Representative Leach tonight. made it possible for us to do what we did to- I thank Israel Singer and the World Jewish gether as Americans, not as Republicans or Council leadership, Elie Wiesel, my fellow Democrats but as Americans. Governor Pataki award recipients, especially Senator D’Amato and Alan Hevesi marshal city and State govern- and Congressman Leach, without which we ments all across America, not as Republicans could not have done our part, and Stuart or Democrats but as Americans. People like Eizenstat, without which I could have done Paul Volcker, Larry Eagleburger, and Stan nothing. And I thank you all. Chesley, all of whom could choose to do pretty I thank the members of the Israeli Govern- much whatever they like, chose instead to spend ment and Cabinet who are here and those of their time and their talents generously on this you who have come from around the world. -

Nd Help Pizza, Pasta & Party with Tal & Roi Local Jewish Teen Stars As

Non-Profit Organization U.S. Postage PAID Norwich, CT 06360 Permit #329 Serving The Jewish Communities of Eastern Connecticut & Western R.I. CHANGE SERVICE RETURN TO: 28 Channing St., New London, CT 06320 REQUESTED VOL. XLV NO. 19 PUBLISHED BI-WEEKLY OCTOBER 11, 2019/12 TISHRI 5780 NEXT DEADLINE OCT. 18, 2019 16 PAGES HOW TO REACH US - PHONE 860-442-8062 • FAX 860-540-1475 • EMAIL [email protected] • BY MAIL: 28 CHANNING STREET, NEW LONDON, CT 06320 Local Jewish Pizza, Pasta & Party teen stars as with Tal & Roi Many people have asked recently if the Jewish Federation will be Anne Frank having its Harvest Supper and Emissary Welcome. We will absolutely be having our Emissary Welcome however, in this year of changes, in- WATERFORDrama, the drama club stead of the Harvest Supper we will have an evening of Pizza, Pasta and at Waterford High School, is proud to Party with the Young Emissaries. Mark your calendars for Thursday, present The Diary of Anne Frank. The Nov. 7 beginning at 6pm at Temple Emanu-El in Waterford. shows will take place Thursday-Sat- We will have salad along with the pizza and pasta and a gluten free urday, October 17 -19 at 7:00pm in alternative. And back by popular demand will be our traditional Har- the Waterford High School Audito- vest Supper Apple Cider and Cider Donuts for dessert and a few other rium. surprises. The show, which kicks off WA- th Some of you may have already met Tal and Roi so come join us for TERFORDrama’s 16 season, features an evening to get to know them even better. -

World Jewish Congress on Eliminating Intolerance and Discrimination Based on Religion Or Belief and the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 16 (SDG 16)

Submission by the World Jewish Congress on Eliminating Intolerance and Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief and the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 16 (SDG 16) Introduction The World Jewish Congress is the representative body of more than 100 Jewish communities around the globe. Since its founding in 1936, the WJC has prioritized the values embodied in SDG 16 for the achievement of peaceful, just and inclusive societies. It does so by, inter alia, countering antisemitism and hatred, advocating for the rights of minorities and spearheading interfaith understanding. Antisemitism is a grave threat to the attainment of SDG 16, undermining the prospect of peaceful, just and inclusive societies which are free from fear and violence. Antisemitism concerns us all because it poses a threat to the most fundamental values of democracy and human rights. As the world’s “oldest hatred,” antisemitism exposes the failings in each society. Jews are often the first group to be scapegoated but, unfortunately, they are not the last. Hateful discourse that starts with the Jews expands to other members of society and threatens the basic fabric of modern democracies, rule of law and the protection of human rights. Antisemitism is on the rise globally. Virtually every opinion poll and study in the last few years paints a very dark picture of the rise in antisemitic sentiments and perceptions. As examples: • According to the French interior ministry, in 2018, antisemitic incidents rose sharply by 74% compared to the year before.1 In 2019, antisemitic acts in the country increased by another 27%.2 • According to crime data from the German government, in 2018 there was a 60% rise in physical attacks against Jewish targets, compared to 2017.3 • In Canada, violent antisemitic incidents increased by 27% in 2019, making the Jewish community the most targeted religious minority in the country.4 1 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/12/world/europe/paris-anti-semitic-attacks.html. -

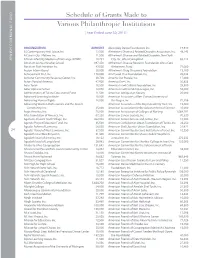

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

Interview: How an Architect and a Judaica Artist Transformed the Park Avenue Synagogue

Park Avenue Synagogue exterior Rendering of Park Avenue Synagogue chapel Photo: Frank Oudeman Courtesy of MBB Architects Interview: How an architect and a Judaica artist transformed the Park Avenue Synagogue By Michelle Sinclair Colman June 13, 2019 In a unique partnership, New York City architect Mary Burnham and Chicago Judaica artist and architect Amy Reichert, who happened to be close friends from col- lege, worked together to renovate the Park Avenue Syn- agogue’s Eli M. Black Lifelong Learning Center. The pair oversaw the gut-renovation of the historic townhome on Manhattan’s Upper East Side as a multipurpose educa- tion facility filled with flexible spaces to accommodate the needs of preschoolers to the elderly in a modern synagogue. CityRealty spoke to Reichert and Burnham to understand what designing a modern synagogue means, how they interpreted traditional Jewish values through design, and how they took design constraints and turned them into Jewish history storytelling gems. Park Avenue Synagogue entrance Photo: Frank Oudeman Amy Reichert is an award winning architect, exhibition designer, and designer of Judaica. Since 1996, when she won second place in the Philip and Sylvia Spertus Judaica Prize for her seder plate, she has participated in invited juried exhibitions in museums around the world. Her work can be seen on display at The Jewish Muse- um, NY, The Jewish Museum, Vienna, The Yale Univer- sity Art Gallery, and The San Francisco Contemporary Jewish Museum. She received her B.A. and M.Arch from Yale University, and combines her studio work with teaching at the School of the Art Institute, Chicago. -

Pres. Rivlin Calls for Unity After Killings

Non-Profit Organization U.S. Postage E PAID Norwich, CT 06360 Permit #329 TH RETURN TO: 28 Channing St., New London, CT 06320 Serving The Jewish Communities of Eastern Connecticut & Western R.I. CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED VOL. XLII NO. 14 PUBLISHED BI-WEEKLY WWW.JEWISHLEADERWEBPAPER.COM JULY 29, 2016/23 TAMMUZ 5776 NEXT DEADLINE AUG. 5, 2016 16 PAGES HOW TO REACH US - BY PHONE 860-442-8062 • BY FAX 860-443-4175 • BY EMAIL [email protected] • BY MAIL: 28 CHANNING STREET, NEW LONDON, CT 06320 Operation Cool Down The Jewish Federation of Eastern CT’s Operation Cool Down program has concluded another successful season – from June 16 through July 22, 2016. During that time the Federation gave out 24 new air conditioners (ACs) and four Please check out our special pull out section gently used, donated ACs. The Federation could not on the life of Elie Wiesel (pages 7-10) do this program without the support and generosity of area businesses, agencies and other Pres. Rivlin calls for l-r: 2013-14 Emissaries Bar Halgoa and May Abudrham met up non-profits. SupportersCore of Plus this with eastern CT’s 2016-17 Emissaries Tal Gilboa and Guy Carmi. Federalyear’s Operation Credit Union; Cool DownChel- unity after killings seaprogram Groton include Bank, Lawrence By Edgar Asher, Ashernet + Memorial Hospital, Tal & Guy on their way here the Norwich Rotary Founda- By Marcia Reinhard, Assistant Director tion. and- - Following the terror attack in the Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray church in Northern France on Tuesday, July 26, Israeli President Their combined generos As we are heading into the last week of July, I am busy prepar Reuven Rivlin reiterated his call for international unity in the- ity allowed us to purchase an ing for the arrival of our new Young Israeli Emissaries at the end- face of the threat of terrorism and religious hatred. -

Solidarity with Israel with Israel

zun,—iuhx JUNE 2002 VOLUME 16 NUMBER 1 SOLIDARITY WITH ISRAEL WASHINGTON, DC April 15, 2002 “Their fate is our fate.” ---Benjamin Meed s the world media screamed its vitriol at the State of Israel, as Jewish ister Benjamin Netanyahu and PM Natan Sharansky delivered their messages, bodies once again piled up and the world closed its eyes yet pointed its there too was House Majority Leader Dick Armey, Minority Leader Dick Gephardt, Acollective finger at the Jews as the culprits responsible for the turmoil, Senators Charles Schumer and Hillary Clinton, Congressman Ben Gilman. There American Jewry called out to meet in Washington, to show the world its sup- was Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz, New York Governor George port for its beleagured brethren. Pataki, former NYC Mayor Rudy Giuliani, and on and on went the list of the And they came—by the carload, the bus load, by plane, by foot. Over 150,00 powerful and not so powerful who came this day to lend their support, to add their descended on Washington, young and old, including many Holocaust survivors names as friends of Israel and as friends of Jews. And God looked down with and Jewish War Veterans. They came to stand together, to let the nations of the great favor on this day. Under a brilliant sun, more and more people came to spill world understand that never again would Jews stand by and let their fellow over beyond the Capitol mall, reaching back to the reflecting pool and expanding Jews be attacked and murdered. And this time they brought their allies with beyond the surrounding avenues.