DEWITT-DISSERTATION-2019.Pdf (2.242Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conserving Common Ground: Exploring the Place of Cultural Heritage in Protected Area Management

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020-12-08 Conserving Common Ground: Exploring the Place of Cultural Heritage in Protected Area Management Weller, Jonathan Weller, J. (2020). Conserving Common Ground: Exploring the Place of Cultural Heritage in Protected Area Management (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112818 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Conserving Common Ground: Exploring the Place of Cultural Heritage in Protected Area Management by Jonathan Weller A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN CALGARY, ALBERTA DECEMBER, 2020 © Jonathan Weller 2020 ii Abstract That parks and protected areas are places where the conservation of cultural heritage can and should take place has not always been immediately apparent. However, today there is widespread acknowledgement that the management of cultural heritage resources needs to be brought into large-scale planning and management processes in an integrated and holistic manner. This is particularly true in protected areas, which not only contain significant cultural heritage resources, but are also often mandated to conserve these resources and can benefit significantly from the effort. -

AWA Response to Castle Park Plan

ALBERTA WHITEWATER ASSOCIATION Water Recreation in Castle Park The new Castle Provincial Park and Castle Wildland Provincial Park proposed by the Government of Alberta will bring changes to recreational activities in southwestern Alberta. The Alberta Whitewater Association (AWA) including its member clubs and paddlers have a long history of paddling the lakes, rivers and creeks in the region. Maintaining access to the paddling opportunities while respecting the environmental integrity of the region are critical goals for the AWA when reviewing the plan for the new Parks. The AWA has 3 paddling clubs in southwest Alberta, the Waterlogged Kayak Club, the Oldman River Canoe Kayak Club in Lethbridge and the Pinch-o-Crow Creekers in Pincher Creek and Crowsnest Pass. The area is the host for the largest whitewater paddling event in western Canada, the 3 Rivers Whitewater Rendezvous. This event has been held outside the Park on the May long weekend for almost 20 years at the Castle River Rodeo Grounds campground. The Alberta Freestyle Kayak Association also holds one of its annual events, the Carbondale Creek Race, on the 5 Alive rapid each year. Paddlers come from all over Alberta, BC and Saskatchewan to paddle in southwest Alberta during the short paddling season each year. Paddling activities by their very nature have a small environmental footprint on the landscape. Human powered watercraft traversing on lakes and rivers are uniQue to recreation in the following ways: - the water trails that paddlers travel across already exist as part of the natural landscape - paddlers do not leave footprints in the river and the boats do not impact the terrain they cross over - water travel is a protected right under Canadian and Alberta law - fish and wildlife may be temporarily displaced but are not permanently affected by paddlers - most other recreational users are not inconvenienced or disturbed by the travel of paddlers along the river. -

Susan Buxton Interim Director Idaho Parks & Recreation

Susan Buxton Interim Director Idaho Parks & Recreation Betty Mills 0.2616187;0.5;359.2124 Management Assistant Debbie Hoopes Anna Canning Craig Quintana Human Resource Management Services Troy Elmore PIO, Sr. Officer Administrator Operations Administrator Jaime Little Experience & Education Program Supervisor Vacant Keith Jones Admin Assistant 1 Seth Hobbs Adam Zaragoza Natural Resource R&R Program Mgr Development Bureau Manager Kathryn Hampton Chief Chelsea Chambers Vacant Garth Taylor PIS Volunteer Services South Region East Region Coordinator Joel Taylor Bureau Chief Bureau Chief Office Serv Spvsr 2 Nadine Curtis Admin Assistant 1 Lupe Arteaga Matt Linde David Landrum RebeccaNadine Honsinger Curtis Joyce Storey Personnel Tech Ponderosa State Park Admin Assistant 1 1000 Island State Park Admin Assistant 2 Vacant Joel Halfhill Gary Shelley Construction Mgr 1 Construction Mgr 1 James Todd Smith Renee Brennan Theresa Perry Eagle Island SP CSR2 TRS2 Lake Cascade SP Wallace Keck Travis Taylor Joseph Cook Castle Rocks/CIRO Massacre State Parks Building Facility Frmn Roxann Cleverly Laura Wallace Bryce Bealba Surat Nicol Bruneau Dunes SP Kirk Rich Vacant CSR2 CSR2 Lucky Peak State Park Bear Lake State Park Lake Walcott SP Lucas Wingert Construction Mgr 1 Lisa Craig Carlene Kirkland Nita Moses Christopher Re Ricky Thompson Mark Eliot CSR2 CSR2 3 Island State Park Rec Site Maint Frmn Land of the Melanie Schuster Yankee Fork Harriman/Henrys SP Jane Young Arch/Eng Proj Mgr, Sr Drue McCombs OS2 Utility Craftsman Erik Bush Design Professional Erik Ryan Design Professional David White David Claycomb North Region Bureau Chief Rec Bureau Chief Steve Martin Tami Delgado David Dahms Vacant Tom Helmer Sam Hoggatt Chief Financial Officer Admin Assistant 2 Program Supervisor Program Supervisor NM Program Coord. -

Analysis of Habitat Fragmentation and Ecosystem Connectivity Within the Castle Parks, Alberta, Canada by Breanna Beaver Submit

Analysis of Habitat Fragmentation and Ecosystem Connectivity within The Castle Parks, Alberta, Canada by Breanna Beaver Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Environmental Science Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY December, 2017 Analysis of Habitat Fragmentation and Ecosystem Connectivity within The Castle Parks, Alberta, Canada Breanna Beaver I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Breanna Beaver, Student Date Approvals: Dawna Cerney, Thesis Advisor Date Peter Kimosop, Committee Member Date Felicia Armstrong, Committee Member Date Clayton Whitesides, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date Abstract Habitat fragmentation is an important subject of research needed by park management planners, particularly for conservation management. The Castle Parks, in southwest Alberta, Canada, exhibit extensive habitat fragmentation from recreational and resource use activities. Umbrella and keystone species within The Castle Parks include grizzly bears, wolverines, cougars, and elk which are important animals used for conservation agendas to help protect the matrix of the ecosystem. This study identified and analyzed the nature of habitat fragmentation within The Castle Parks for these species, and has identified geographic areas of habitat fragmentation concern. This was accomplished using remote sensing, ArcGIS, and statistical analyses, to develop models of fragmentation for ecosystem cover type and Digital Elevation Models of slope, which acted as proxies for species habitat suitability. -

Alberta with the Establishment of Castle the Following Conservation Achievements

Annual Report 2017 in Review The Yellowstone to Table of contents Yukon region A letter from Jodi 3 Key advancements 4 in the Y2Y region Dawson Protected areas and 6 connected lands Solutions that help wildlife and 8 Whitehorse people thrive Advancing science and policy 10 Communities coming together 12 for conservation Partner power 14 Fort St. John Funders 16 Prince George Financials 17 Edmonton Global support 18 Banff Vancouver Calgary Our vision Seattle Spokane Missoula An interconnected system of wild lands and water stretching Bozeman from Yellowstone to Yukon, Jackson harmonizing the needs of Boise people with those of nature. Our mission Connecting and protecting habitat from Yellowstone to Yukon so that people and nature can thrive. 2 Cover: Elk nuzzle. Photo credit: Darcy Monchak. Current page: Larches at Avalanche Lake in Glacier National Park. Photo credit: Jacob W. Frank/National Park Service. Big landscape requires big vision A letter from our President and Chief Scientist ellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) Conservation This annual report throws a spotlight on some YInitiative’s grand vision — of an of the many organizations and individuals interconnected system of wild lands and working toward a sustainable future. These waters from Yellowstone to Yukon, groups and people have contributed time, harmonizing the needs of people with funds and expert knowledge to the bigger those of nature — takes time, resources picture and we thank them for it. and commitment. Effective large-landscape Thanks to your support and shared vision for conservation requires invested and interested a healthy landscape, we are able to make the individuals. It goes beyond financial progress you can read about in these pages. -

AGENDA COUNCIL MEETING MUNICIPAL DISTRICT of PINCHER CREEK June 12, 2018 1:00 Pm

AGENDA COUNCIL MEETING MUNICIPAL DISTRICT OF PINCHER CREEK June 12, 2018 1:00 pm A. ADOPTION OF AGENDA B. DELEGATIONS 1. Grant Writer Update - Email from Pincher Creek & Area Early Childhood Coalition, dated May 30, 2018 C. MINUTES 1. Council Committee Meeting Minutes - May 22, 2018 2. Council Meeting Minutes - May 22, 2018 D. UNFINISHED BUSINESS 1. Landfill Road Maintenance Agreement Reply - Report from Director of Operations, dated June 6, 2018 E. CHIEF ADMINISTRATOR OFFICER’S (CAO) REPORTS 1. Operations a) Spring Road Tour - Council to schedule a date for the road tour b) Cowley Lions Club – Request for Gravel - Report from Director of Operations, dated June 6, 2018 c) Beaver Mines Water and Wastewater Project Briefing - Briefing dated June 7, 2018 d) Operations Report - Report from Director of Operations, dated June 6, 2018 - Call Log 2. Planning and Development a) Beaver Mines Community Association Request for Subdivision Moratorium - Report from Director of Development and Community Services, dated June 6, 2018 b) Event Licence – Mud Bog, SW 7-6-28 W4M - Report from Director of Development and Community Services, dated June 6, 2018 3. Finance a) Public Auction – Conditions and Reserve Bids - Report from Director of Finance, dated June 1, 2018 b) Statement of Cash Position - For Month Ending May 2018 4. Municipal a) Interim Chief Administrative Officer Report - Report from Interim Chief Administrative Officer, dated June 7, 2018 - Call Log F. CORRESPONDENCE 1. For Action a) Special Advocacy Fund - Brochure and Funding Request from -

Castle Summer Map Side 2017

Important Note: This interim Castle Park Guide is for the 2017 summer season only. Revisions will occur following approval of the Camp Responsibly Recreate Responsibly Know Before You Go Castle Parks Management Plan. Welcome to the Castle Parks The Castle parks offer diverse camping experiences in frontcountry and remote backcountry settings. All camping in the Trails It is your responsibility to become familiar with the activities allowed in this area before you visit. Refer to the information Castle parks requires a permit, and the daily checkout time is at 2 pm. The maximum stay in any campsite is 16 consecutive and map in this publication for further details, pick-up or download the Alberta Parks regulations brochure, look for park Encompassing more than 105,000 hectares, the new In 2017, all trails in the Castle parks will be assessed to inform the development of a trails strategy. Be aware that most trails nights. All camping in the Castle parks is rst come, rst served, except the Syncline Group Camp, available by reservation information kiosks, and contact us if you have any questions. Visitors who do not follow the rules could be ned or charged Castle Provincial Park and Castle Wildland Provincial are not yet improved, and natural hazards are prevalent. only. under provincial legislation. Contact information is printed on the back panel of this publication. Park in southwest Alberta protect valuable watersheds and habitat for more than 200 rare species such as Campgrounds in Castle Provincial Park Hiking & Biking Alberta Parks Regulations whitebark and limber pine, Jones’ columbine, dwarf Hikers are free to explore both the Provincial Park and Wildland Provincial Park. -

Members' Magazine

MEMBERS’ MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2018 Supporting the Human-Animal Bond Alberta Helping Animals Society 2018 VETERINARY PRESENTED BY FORENSICS WORKSHOP From routine investigations to cases that end up in court, veterinary forensics is an emerging area of study in the veterinary profession. Put your skills to the test at this two day workshop featuring: • Veterinary Forensics 101: Investigations, • Panel presentation with ABVMA, Animal Evidence Collection, Forensic Reports, Care and Control (ACC) Edmonton, Alberta Toxicology, Pathology Agriculture and Forestry, (AAF) Calgary Dr. Margaret Doyle, Riverbend Veterinary Humane Society (CHS), Alberta SPCA (ABSPCA) Clinic, and Mr. Brad Nichols, Calgary Dr. Phil Buote - (ABVMA), Mr. Keith Scott Humane Society (ACC), Dr. Hussein Keshwani (AAF), Mr. Brad • Issues with Recongition and Reporting: Nichols (CHS), Mr. Ken Dean (ABSPCA) Six Stages of Veterinary Response to • Solve the Case, dinner and networking event - Animal Cruelty, Abuse and Neglect submit your case slides for an open discussion Dr. Phil Arkow, The National Link Coalition of various forensics cases • The Animal Abuse/Family Violence Link and • Preparing for Court Its Implications for Veterinary Social Work Ms. Rose Greenwood, Crown Prosecutor, Dr. Phil Arkow, The National Link Coalition Justice and Solicitor General • Emotional Suffering of Animals or People in • Necropsy, handling the post-mortem Animal Abuse Cases Dr. Nick Nation, Animal Pathology Services Ltd. Dr. Rebecca Ledger, Animal Behaviour and • Compiling the Case for Trial Welfare Scientist, Langara College Crime Scene Photography • The Animal Protection Act in Alberta Constable Stuart Saunders, Edmonton - it’s impact on various organizations. Police Service Role of Vet and Tech Teams in the Field Mr. -

Contact Visitor Information Recreate Responsibly Castle

Welcome to the Castle Parks Pass Library. There are track set trails for skiers. Winter Guide Visitor Just snowshoe alongside, not over top, so you Contact Encompassing more than 105,000 hectares, don’t disturb the ski trail. Camp Responsibly Castle Provincial Park and Castle Wildland Provincial Park in southwest Alberta protect Information Or join park staff on a winter snowshoe The Castle Parks offer diverse camping Alberta Parks Pincher Creek Office valuable watersheds and habitat for more than adventure exploring the new Castle Park, its experiences in both the front country and the Phone: (403) 627–1165 200 rare species such as whitebark and limber wildlife and landscape, while enjoying a day backcountry. Visitors should be aware that Toll-Free: 310–0000 pine, Jones’ columbine, dwarf alpine poppy, Visitor information is available at kiosks located outdoors! upgrades to existing facilities in the park are Visitor Services: (403) 627–1152 Castle grizzly bear, wolverine, westslope cutthroat trout, throughout the parks, at albertaparks.ca/castle, ongoing, to improve camping experiences for bull trout and harlequin duck. The parks share by calling 403–627–1165, or by speaking with Alberta Parks is working to provide adaptive visitors in the future. General Provincial Park Information Provincial Park & borders with the Waterton Biosphere Reserve to Alberta Parks staff. equipment in order to promote accessibility to Web: albertaparks.ca Wildland Provincial Park the east, Waterton-Glacier International Peace trails in all seasons for people of all abilities. Campgrounds in Castle Provincial Park Toll Free: 1–866–427–3582 Park to the south, the Crowsnest Pass to the Local communities offer a wide range of For more information search for “Push to Open north and the Flathead River Valley of British services to complement your visit including Nature” at albertaparks.ca. -

Residents Guide

General Reference Guide for CASTLE MOUNTAIN RESORT Updated April 2018 1 THE CORPORATION - Castle Mountain Resort .............................................................................................................. 3 THE COMMUNITY - Castle Mountain Community Association .................................................................................. 4 THE MD OF PINCHER CREEK ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Castle Provincial ParKs ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 EMERGENCY SERVICES ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 PARKING AND MAPS ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Figure 1: Winter Village Area Map .............................................................................................................................................. 8 Figure 2: West Castle Valley Winter Multi-Use Trails .............................................................................................................. 9 Figure 3: Summer Hiking Trail Guide ........................................................................................................................................ -

Camp Responsibly Recreate Responsibly Know Before You Go Castle Parks Management Plan

Important Note: This interim Castle Park Guide is for the 2017 summer season only. Revisions will occur following approval of the Camp Responsibly Recreate Responsibly Know Before You Go Castle Parks Management Plan. Welcome to the Castle Parks The Castle parks offer diverse camping experiences in frontcountry and remote backcountry settings. All camping in the Trails It is your responsibility to become familiar with the activities allowed in this area before you visit. Refer to the information Castle parks requires a permit, and the daily checkout time is at 2 pm. The maximum stay in any campsite is 16 consecutive and map in this publication for further details, pick-up or download the Alberta Parks regulations brochure, look for park Encompassing more than 105,000 hectares, the new In 2017, all trails in the Castle parks will be assessed to inform the development of a trails strategy. Be aware that most trails nights. All camping in the Castle parks is rst come, rst served, except the Syncline Group Camp, available by reservation information kiosks, and contact us if you have any questions. Visitors who do not follow the rules could be ned or charged Castle Provincial Park and Castle Wildland Provincial are not yet improved, and natural hazards are prevalent. only. under provincial legislation. Contact information is printed on the back panel of this publication. Park in southwest Alberta protect valuable watersheds and habitat for more than 200 rare species such as Campgrounds in Castle Provincial Park Hiking & Biking Alberta Parks Regulations whitebark and limber pine, Jones’ columbine, dwarf Hikers are free to explore both the Provincial Park and Wildland Provincial Park. -

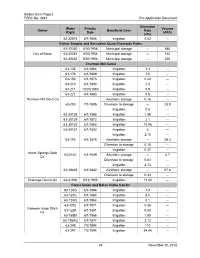

Barber Dam Project FERC No. 4881 Pre-Application Document 38

Barber Dam Project FERC No. 4881 Pre-Application Document Diversion Water Priority Volume Owner Beneficial Uses Rate Right Date (AFA) (cfs) 63-32816 5/1/1866 Irrigation 0.02 -- Esther Simplot and Bernadine Quinn Riverside Parks 63-32350 8/30/1956 Municipal storage -- 560 City of Boise 63-32351 8/30/1956 Municipal storage -- 140 63-32352 8/30/1956 Municipal storage -- 220 Thurman Mill Canal 63-135 6/1/1864 Irrigation 3.3 -- 63-176 6/1/1869 Irrigation 1.6 -- 63-193 6/1/1876 Irrigation 0.44 -- 63-210 6/1/1880 Irrigation 2.4 -- 63-211 10/20/1880 Irrigation 0.9 -- 63-221 6/1/1883 Irrigation 0.9 -- Thurman Mill Ditch Co Aesthetic storage 0.16 -- 63-250 7/1/1895 Diversion to storage -- 23.9 Irrigation 0.5 -- 63-30125 6/1/1865 Irrigation 1.86 -- 63-30129 6/1/1872 Irrigation 2.1 -- 63-30130 6/1/1868 Irrigation 15.48 -- 63-30131 6/1/1882 Irrigation 6 -- Irrigation 2.15 -- 63-192 6/1/1876 Aesthetic storage -- 26.3 Diversion to storage 0.15 -- Irrigation 0.37 -- Warm Springs Ditch 63-216C 6/1/1889 Aesthetic storage -- 4.7 Co. Diversion to storage 0.03 -- Irrigation 4.73 -- 63-19425 6/1/1882 Aesthetic storage -- 57.8 Diversion to storage 0.33 -- Drainage District #4 63-31936 8/13/1925 Irrigation 11.42 -- Farms Union and Boise Valley Canals 63-120G 6/1/1864 Irrigation 1.8 -- 63-123C 6/1/1864 Irrigation 8.4 -- 63-124Q 6/1/1864 Irrigation 0.1 -- 63-125J 6/1/1871 Irrigation 0.26 -- Farmers Union Ditch 63-126F 6/1/1891 Irrigation 0.08 -- Co.