Pathways to the Paralympic Games: Exploring the Sporting Journeys Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games

TOKYO 2020 PARALYMPIC GAMES QUALIFICATION REGULATIONS REVISED EDITION, JULY 2020 INTERNATIONAL PARALYMPIC COMMITTEE 2 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games Programme Overview 3. General IPC Regulations on Eligibility 4. IPC Redistribution Policy of Vacant Qualification Slots 5. Universality Wild Cards 6. Key Dates 7. Archery 8. Athletics 9. Badminton 10. Boccia 11. Canoe 12. Cycling (Track and Road) 13. Equestrian 14. Football 5-a-side 15. Goalball 16. Judo 17. Powerlifting 18. Rowing 19. Shooting 20. Swimming 21. Table Tennis 22. Taekwondo 23. Triathlon 24. Volleyball (Sitting) 25. Wheelchair Basketball 26. Wheelchair Fencing 27. Wheelchair Rugby 28. Wheelchair Tennis 29. Glossary 30. Register of Updates INTERNATIONAL PARALYMPIC COMMITTEE 3 INTRODUCTION These Qualification Regulations (Regulations) describe in detail how athletes and teams can qualify for the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games in each of the twenty- two (22) sports on the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games Programme (Games Programme). It provides to the National Paralympic Committees (NPCs), to National Federations (NFs), to sports administrators, coaches and to the athletes themselves the conditions that allow participation in the signature event of the Paralympic Movement. These Regulations present: • an overview of the Games Programme; • the general IPC regulations on eligibility; • the specific qualification criteria for each sport (in alphabetical order); and • a glossary of the terminology used throughout the Regulations. STRUCTURE OF SPORT-SPECIFIC QUALIFICATION -

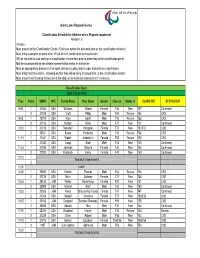

PI Classification Schedule GLRG.Xlsx

Great Lakes Regional Games Classification Schedule for Athletes with a Physical Impairment Version 1.6 Athletes - Must present to the Classification Centre 15 minutes before the allocated time on the classification schedule. Must bring a passport or some other official form of identification to classification. Will be required to read and sign a classification release form prior to presenting to the classification panel. May be accompanied by one athlete representative and/or an interpreter. Must be appropriately dressed in their sport clothes including shorts under tracksuits and sport shoes. Must bring their track chairs, strapping etc that they will be using in competition, to the classification session. Must ensure their throwing frames are at the stadium for technical assessments if necessary. Classification Day 1 Date: 9 June 2016 Time Panel SDMS NPC Family Name First Name Gender Class In Status In CLASS OUT STATUS OUT 9:00 1 31066 USA Williams Taleah Female T46 New T47 Confirmed 2 31008 USA Croft Philip Male T54 Review T54 CRS 9:45 1 15912 USA Rigo Isaiah Male T53 Review T53 CRS 2 31016 USA Nelson Brian Male F37 New F37 Confirmed 10:30 1 31218 USA Beaudoin Margaret Female T37 New T37/F37 CNS 2 30821 USA Evans Frederick Male T34 Review F34 CRS 11:15 1 11241 USA Weber Amberlynn Female T53 Review T53 CRS 2 31330 USA Langi Siale Male F43 New F43 Confirmed 11:45 1 31098 USA Johnson Shayna Female T44 New T44 Confirmed 2 27200 USA Frederick Emily Female F40 New F40 Confirmed 12:15 1 Technical Assessments 2 13:00 Lunch 14:00 1 20880 USA -

SECURITY COUNCIL COMMITTEE ESTABLISHED in PURSUANCE of RESOLUTION 253 (1968) CONCERNING the QUESTION of SOUTHERN Rhcldesia SECURITYCOUNCIL OFFICIALRECORDS

SIXTH REPORT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL COMMITTEE ESTABLISHED IN PURSUANCE OF RESOLUTION 253 (1968) CONCERNING THE QUESTION OF SOUTHERN RHClDESIA SECURITYCOUNCIL OFFICIALRECORDS TWENTY-NINTH YEAR SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT No. 2A UNITED NATIONS annex Vi. eppendlx III SIXTH REPORT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL COMMITTEE ESTABLISHED IN PURSUANCE OF RESOLUTION 263 (lB68) CONCERNING THE QUESTION OF SOUTHERN RHODESIA SECURITYCOUNCIL OFFICIALRECORQS TWENTY-NINTH YEAR SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT No. 2A UNITED NATIONS New York, 1974 NOTE Symbola of United Nations documenh an? composed of cvpftalbttm combined wfth &~rss. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations doewnent. Documentaof the SecurityCouncll(symbo1 S/. .) arenormally published in quartsrly Slrpplements of fha Offi& Records of the Secur&v Council Thedate of thedocument indicatesthe aupplemnt in whichit appearsor in whichinformation about it iagiven. The maolutioncof the SecurityCouncil, numbered tn accordancewith a system adoptedin 1964,am publinhed in yearlyvolunws of Resolutionr and DeciAwts of the &cur@ CacncN.The new system, which has bean applied retroactively to ~saolution~ adoptedbefore 1 January1965, became fully operativeon that data. Sfiii70lRev.i m(rx VI, appendixIII I I e The sixth report of the Security Council Committee established in pursuance of resolution 253 (1968) concerning the question of Southern Rhodesia is published as Special Supplement No. 2. The present Supplement contains the tables entitled "Trade in commodities", issued aa annex VI, appdndfx III, to the above report. The tables are issued in the form in which they were presented to the Committee and the Council. NOTE: A DASH (-) INDICATES NIL, LESS THAN $US 1,000, OR FIGURES NOT AVAILABLE. -iii- AFRICA EUROPE LIT4fR ____-_--_--____-_---_--__-_______---_-___-_____~___ I)ESlLUI I YESTRY ASIA SOUTMRY S.AFR. -

All 12 Wcha Men's-Member Teams to Engage in League

WESTERN COLLEGIATE HOCKEY ASSOCIATION Bruce M. McLeod Commissioner Carol LaBelle-Ehrhardt Assistant Commissioner of Operations Greg Shepherd Supervisor of Officials Administrative Office Western Collegiate Hockey Association November 26, 2012/For Immediate Release 2211 S. Josephine Street, Room 302 Denver, CO 80210 ALL 12 WCHA MEN’S-MEMBER TEAMS TO ENGAGE IN LEAGUE p: 303 871-4491. f: 303 871-4770 [email protected] PLAY NOVEMBER 30-DECEMBER 1 … IT’S UMD AT MTU, UNO AT Doug Spencer Associate Commissioner for UM, BSU AT MSU, UW AT DU, UND AT CC, SCSU AT UAA Public Relations MINNESOTA STATE GAINS THANKSGIVING WCHA SWEEP AT UW; BEMIDJI STATE EARNS THREE Western Collegiate Hockey Association 559 D’Onofrio Drive, Ste. 103 POINTS FROM UAA; SCSU SPLITS AT UMD; WEEKEND RESULTS SEE MINNESOTA SWEEP AT Madison, WI 53719-2096 VERMONT, HOST NEBRASKA OMAHA DOWN UAH TWICE AS LEAGUE TEAMS GO 5-4-1 IN NON- p: 608 829-0100. f: 608 829-0200 [email protected] CONFERENCE PLAY; GOPHERS, UNO MAVERICKS UNBEATEN OVER LAST SIX; LATEST DIVISION 1 MEN’S NATIONAL POLLS HAVE UM NO. 3, DU NO. 5, UND NO. 7/8, UNO NO. 13/14, SCSU NO. HOME OF A COLLEGIATE RECORD 37 14/15, CC NO. 18 … MSU RECEIVES VOTES MEN’S NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP TEAMS SINCE 1951 MADISON, Wis. – The first of two consecutive weekends that will feature all 12 Western Collegiate Hockey 1952, 1953, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, Association men’s-member teams engaged in conference play will occur this Friday and Saturday, Nov. 1965, 1966, 1968, 1969, 1973, 1974, 30 and Dec. -

Athletics Classification Rules and Regulations 2

IPC ATHLETICS International Paralympic Committee Athletics Classifi cation Rules and Regulations January 2016 O cial IPC Athletics Partner www.paralympic.org/athleticswww.ipc-athletics.org @IPCAthletics ParalympicSport.TV /IPCAthletics Recognition Page IPC Athletics.indd 1 11/12/2013 10:12:43 Purpose and Organisation of these Rules ................................................................................. 4 Purpose ............................................................................................................................... 4 Organisation ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Article One - Scope and Application .................................................................................. 6 International Classification ................................................................................................... 6 Interpretation, Commencement and Amendment ................................................................. 6 2 Article Two – Classification Personnel .............................................................................. 8 Classification Personnel ....................................................................................................... 8 Classifier Competencies, Qualifications and Responsibilities ................................................ 9 3 Article Three - Classification Panels ................................................................................ 11 4 Article Four -

Athletes with Physical Impairment

Nottwil 2019 World Para Athletics Junior Championships Version 4 Classification Schedule for Athletes with Physical Impairment Athletes - Must present to classification 30 minutes before the allocated time on the classification schedule. Must bring a passport or some other official form of identification along with their accreditation. Will be required to read and sign a Athlete Evaluation Agreement Form prior to presenting for Athlete Evaluation. Must be accompanied by an interpreter if the athlete does not speak English. May be accompanied by one athlete representative. Must attend with all relevant medical documentation (in English). Must wear shorts for classification. Must bring all sports equipment and competition clothing including shoes to be used in competition (for technical Must ensure their throwing frames/racing wheelchairs are at the stadium for technical assessments if necessary. Location: Stadium Date: 29 July 2019 Time SDMS NPC Family Name First Name Gender Class Status 08:30 32059 BRN Alhaddar Mohamed Male F32 Review 08:30 43445 BRA Da Silva Picetti Wesley Male T/F35 New 08:30 42956 IND Bhatiwal Vikash Male F46 New 09:15 34097 CRO Kaurin Erik Fabian Male T47/F46 FRD2019 09:30 43297 CRO Kosmat Antonio Male T38 New 09:30 43442 BRA Luis Da Costa Christian Gabriel Male T37 New 10:00 41769 JPN Yamamura Kaito Male T47/F46 New 10:30 43342 FIN Berg Vilma Female T38 New 10:30 42621 GER Groth Helen Female T/F35 New 10:45 43155 RSA Lekhehle Obed Male T/F42 New 11:30 43441 BRA Martins Da Costa Jose Alexandre Male T47 New Location: -

ATHLETICS Medal Events Male Female Mixed Total 93 74 1 (Universal Relay) 168 Detailed Medal Events List at the End of This Chapter

ATHLETICS Medal Events Male Female Mixed Total 93 74 1 (Universal Relay) 168 Detailed Medal Events List at the end of this chapter Athlete Quota Male Female Gender Free Total 630 470 0 1100 Allocation of Qualification Slots An athlete may only obtain a maximum of one qualification slot. The qualification slot is allocated to the NPC not to the individual athlete. In case of a Bipartite Commission Invitation the slot is allocated to the individual athlete not to the NPC. Maximum Quota Allocation per NPC An NPC can be allocated a maximum of forty-five (45) male qualification slots and thirty-five (35) female qualification slots. Exceptions may be granted through the Bipartite Commission Invitation Allocation method. If an NPC is unable to use all of the allocated qualification slots in a given gender, the unused slots cannot be transferred to the other gender. They will be reallocated in the respective gender to other NPCs through the Bipartite Invitation Commission Allocation method. Athlete Eligibility To be eligible for selection by an NPC, athletes must: . hold an active World Para Athletics Athlete Licence for the 2020 season; . have achieved one (1) Minimum Entry Standard (MES) performance at a World Para Athletics Recognised Competition (IPC Competition, WPA Sanctioned Competition, or WPA Approved Competition) for each of their respective events between 1 October 2018 and 2 August 2020 in accordance with the IPC Athlete Licensing Programme Policies valid Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games – Qualification Regulations Athletics for the 2018-2020 seasons – exceptions may be made via the Bipartite Commission Invitation Allocation method; and . -

Publication 938 (Rev. November 2019) Introduction

Userid: CPM Schema: tipx Leadpct: 100% Pt. size: 8 Draft Ok to Print AH XSL/XML Fileid: … ons/P938/201911/A/XML/Cycle02/source (Init. & Date) _______ Page 1 of 120 10:35 - 19-Nov-2019 The type and rule above prints on all proofs including departmental reproduction proofs. MUST be removed before printing. Publication 938 (Rev. November 2019) Introduction Cat. No. 10647L Section references are to the Internal Revenue Department Code unless otherwise noted. of the This publication contains directories relating Treasury to real estate mortgage investment conduits Real Estate (REMICs) and collateralized debt obligations Internal (CDOs). The directory for each calendar quarter Revenue is based on information submitted to the IRS Service Mortgage during that quarter. For each quarter, there is a directory of new REMICs and CDOs and, if required, a section Investment containing amended listings. You can use the directory to find the representative of the RE- MIC or the issuer of the CDO from whom you Conduits can request tax information. The amended list- ing section shows changes to previously listed REMICs and CDOs. The update for each calen- (REMICs) dar quarter will be added to this publication ap- proximately six weeks after the end of the quar- Reporting ter. Publication 938 is only available on the In- ternet. To get Publication 938, including prior is- Information sues, visit IRS.gov. Future developments. The IRS has created a page on IRS.gov that includes information (And Other about Publication 938 at IRS.gov/Pub938. Infor- mation about any future developments affecting Collateralized Debt Publication 938 (such as legislation enacted af- Obligations (CDOs)) ter we release it) will be posted on that page. -

TOUR Championship Field Bios, Fedexcup History

TOUR Championship field bios, FedExCup history Patrick Cantlay – No. 1 (-10) __________________ 2020-21 season notes: Wins: 3, ZOZO CHAMPIONSHIP @ SHERWOOD, the Memorial Tournament presented by Workday, BMW Championship Starts: 23 Top-10s: 6 How he qualified for the TOUR Championship: • Held a share of the lead after the second and third rounds of the Shriners Hospitals for Children Open before finishing T8 • Shot a final-round 65 to win the ZOZO CHAMPIONSHIP @ SHERWOOD, earning his third career PGA TOUR victory in his 101st career start. Victory came in his native California after the tournament moved from Japan due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Made nine birdies in the final round to edge Jon Rahm and Justin Thomas by a stroke • Shot a final-round 61 to finish solo-second at The American Express, one stroke shy of Si Woo Kim's 23-under total. Made 20 birdies over the final 36 holes, becoming the first player on record (since 1983) to make 20 or more in the final two rounds of a 72-hole non-major PGA TOUR event • Held a two-stroke lead after 18 holes of the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am before finishing T3. Shot a first-round 62, becoming the third player in tournament history to shoot a 62 or better at Pebble Beach Golf Links; took over the FedExCup standings lead with the finish • Defeated Collin Morikawa in a playoff to win the Memorial Tournament presented by Nationwide for the second time, earning his fourth PGA TOUR title and second of the season; became the seventh multiple winner of the Memorial Tournament and third past Jack Nicklaus -

Metropolitan

Normandie #9 Vol. 3 No. 8 TheMetropolitan NEW DIRECTOR, CRESCENT CC & PEVELY OPERATIONS TO COME FARMS HAVE NEW OWNER AND NEW TTITUDE ON BOARD IN FEBRUARY A PAGE 5 PAGE 16 MAGA HONORED BY MAGA PLAYER’S OF THE Bellerive Wins Their USGA FOR THE SECOND YEAR 6th MAGA Cup Title YEAR IN A ROW PAGE 20-21 Page 6 Page 4 BOONE VALLEY Yardage Books on TO HOST Tour: How the Pro’s USGA GIRL’S JUNIOR really see the course JULY 24-29, 2017 Page 8 PAGE 22 AMATEUR SERIES OLYMPIC TROPHIES FINAL STANDINGS Executive Director Curt Rohe PAGE 22 PAGE 11 arrived in Florida in early December for the Annual USGA GHIN Users NORWOOD HILLS TO Meeting expecting to see familiar faces ST. LOUIS GOLF HISTORY HOST 2018 U.S. LPGA EVENTS and see which organization would be WOMEN’S MID-AMATEUR IN THE MID-1950S ARE honored by the USGA for its service Page 23 SHOWCASE EVENTS FOR to Member Clubs. As the 2015 winner LPGA FOUNDERS in the Medium GHIN category, he was PAGE 12 looking forward to congratulating the 2016 FINAL STANDINGS 2016 winner. AMATEUR AND SENIOR When the Metropolitan’s name PAGE 23-24 JAYNE WATSON NAMED was called as the 2016 winner he was JOE DEY AWARD RECIPIENT overwhelmed. Winning two years in a FOR 2017 2017 SCHEDULE row is not something normally done. PAGE 14 NEARLY COMPLETE Read more about Curt’s reaction on PAGE 13 page 4. Metropolitan Amateur Golf Association • 11777 Clayton Rd. • St. Louis, Missouri 63131 314.567.MAGA • Fax: 314.261.9250 • [email protected] The Metropolitan November - December 2016 STAFF Executive Director Curt Rohe - [email protected] CURT’S COMMENTS Director, Operations Maggie Smith - [email protected] Happy New Year! I hope this final edition of The Metropolitan for 2016 finds P.J. -

International Terrorism >'; / ~'

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. TER~\PRISTIC AC.TIVITY-) International Terrorism >'; / ~' BEFORE THE ,~'!, : "'< SUBCOMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE AD})!IINISTRATION OF THE INTERNAL SECURITY AOT AND OTHER INTERNAL SECURITY LAWS " i 0]' THE J COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE NINETY-FOURTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION t l 1 '-..::) PART 4 " r I MAY 14, 1975 - t "" \ Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary (S J. f u.s. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE If) WASHINGTON : 1975 ale by the Supurlntendent or Documents, U.S. Government I'rluting Office '~1.- Washington, D.C. 2(H02· Prico $1.20 ~,¢ ",.IJ ----------,:!'-.------------.pe:-------------------~----------....,.---...,-------------- -----~ ---~ ----~- COMMITTEE;ON THE JUDICIARX ~ .. ~ JA1v1ES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi, Chairman JOHN,L.lIfCOLELLAN, Arknnsus ROMAN L. HRUSKA,NebrasKa PlIILIP A.lIART, Michigan :Ej:IRAM L. FONo-, lIawnll EDWARD l\I. KENNEDY, lIfassachnsetts lIUOli SCOTT, Pennsylvania BIROliBAYlI,lndlone., . , STROIlITllVRMO))/D, South, (jarollnn QUENTIN N. B URDWK, North Dakotil CHARLES .1ireO. ¥A'I'HrAS, ,JR.,; 1\1'nt'Yland ROBERT O. BYRD, West Virginia WILLIAi\f L. SCQTT, Vlrglnlii CONTENTS JOliNI'. TUNNEY, California . Testimony of: JAMES ABOUREZK, SOUt11 D.~kota Mr.London, Brian Crozier,England director ___________________________________________ of the Institute for the Study of Conflict, _ Page 179 Hon. Robert A. Feurey) Special Assistant to the Secretary of l:ltate, Coordinator for Combatting Terrorism, Department of State, SUBCOMMITTEE To INVESTIGATE THE Am.iulISTRATION OF THE INTERN,\L accompanied by lVl!:. Louis Fields and ;dr. John N. Gatch, Deputy __ 212 Appendix ________________ '________________ ~ _______________________ _ SECURa'y ACT ANn OTHE:J;li INT,E::aNA;L SECURITY LAWS 253 JA?>ms o. -

Inclusive Coaching Guidance for Ambulant Athletes

Inclusive Coaching Guidance for Ambulant Athletes Building confidence and supporting coaches to include athletes of all abilities Compiled and written by Alison O’Riordan for England Athletics Photos by Job King & Alison O’Riordan Start Inclusive Coaching Guidance for Ambulant Athletes 2 Inclusive Coaching Guidance for Ambulant Athletes This document contains information to support coaches to do what they do best - coach athletics to athletes of all abilities! It has an event group focus as below: • Ambulant sprints • Ambulant jumps • Ambulant throws • Ambulant endurance It is an interactive guidance document and is designed so you can move in and out of the sections you are interested in. Please note when clicking on the links that some may open in a window behind the current window. www.englandathletics.org www.englandathletics.org www.englandathletics.org/east Inclusive Coaching Guidance for Ambulant Athletes 3 Contents 1 Introduction/Access 2 Consistent coaching principles 2.1 Adaption & Inclusion 3 Classification Information 3.1 Classification –what the letters and numbers mean 4 Disabled Athlete Pathway 4.1 Paralympic Pathway 5 Event Specific Information 5.1 Ambulant Sprinting, Jumping, Throwing & Endurance 5.2 Wheelchair (seated) throwing and racing 6 Introductory Coaching Considerations 6.1 Coaching Ambulant Sprints – An introduction Ambulant Sprints – Sports Specific Rules 6.2 Coaching Ambulant Jumps – An Introduction Ambulant Jumps – Sports Specific Rules Ambulant Long Jump – Athletics 365 6.3 Coaching Ambulant Throws – An Introduction