Janet Snyder, Early Gothic Column-Figure Sculpture in France

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orleans > Chartres > Dreux

ORLEANS > CHARTRES > DREUX Avec Transbeauce Nos chargés de clientèle SEMAINE DIMANCHES ET FERIES Bougez autrement... vous accueillent 7 jours / 7 Ligne N°1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 1 1 1 1 1 Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma AGENCE Jours de circulation Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Ma Lu Me Je Me Je Lu Me Je Lu Me Je Lu Me Je Me Je Me Je Me Je Me Me Je Me Je Ve Ve Ve Me Je Ve Ve Ve Me Je Me Je Ve Ve Me Je Je Me Je Me Je Ve Ve Ve Sa Sa Sa Sa Sa Sa Di Di Di Di Di (sauf jours fériés) Me Je Me Je Me Je Me Je À chacun son titre TÉLÉPHONE DE Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve Ve F F F F F CHARTRES Notes à consulter 1 - 12 6 1 1 - 2 1 - 12 2 2 - 10 15 1 8 5 5 5 1 5 5 1 5 14 11 SI VOUS VOYAGEZ DE TEMPS EN TEMPS OPTEZ POUR : Gare Routière FONCTIONNEMENT DU RÉSEAU : ORLEANS - La Source : • 0 812 04 28 28 • lundi 31 août 2015 : période de petites vacances scolaires. Le billet simple, en vente à bord des véhicules ou en gare • Lundi : 5h30-20h La Source Résidence des Châtaigniers 12:25 12:30 13:20 14:20 14:20 14:20 15:20 16:35 17:05 17:05 18:00 18:25 19:10 12:20 13:30 18:20 20:00 routière. -

Chartres / Illiers-Combray Veloscenic : Paris to Mont-Saint-Michel Cycle Route

http:www.veloscenie.com 09/03/2021 Chartres / Illiers-Combray Veloscenic : Paris to Mont-Saint-Michel cycle route After a last look back at luminous Chartres Cathedral, this stage leads you on towards the Loir (without an 'e') Valley and Illiers-Combray. This place is devoted to memory of the great novelist Marcel Proust. Around Illiers, the countryside begins to change from the Beauce Plain to the more undulating landscapes that typify the Perche area. Itinerary You leave Chartres following the Eure Valley west. You rejoin the Beauce Plateau, where a network of cycle tracks leads to Fontenay-sur-Eure. Then you continue on quiet roads through cereal-farming country down to Illiers-Combray. Note that there are few facilities for Départ Arrivée cyclists along this stage of the route. Chartres Illiers-Combray Take care when using the bicycle path between Lucé and Fontenay-sur-Eure. Some bumps have been Durée Distance reported (May 2020). 2 h 10 min 32,65 Km Railway station Niveau I cycle often Chartres station : many Express Regional Transport (TER) from and to Paris-Montparnasse Illiers-Combray station : many Express Rgional Transport (TER) from and to Chartres Tourism Offices Chartres : +33 2 37 18 26 26 Illiers-Combray : +33 2 37 24 24 00 Not to be missed Chartres : the cathedral - The International Centre of stained glass, +33 2 37 21 65 72 - The fine arts museum, +33 2 37 90 45 80 - The picassiette house – parks and gardens Illiers-Combray : Aunt Léonie's House (A la Recherche du temps perdu - Marcel Proust) – wash house Voie cyclable Liaisons Sur route Alternatives Parcours VTT Parcours provisoire Départ Arrivée Chartres Illiers-Combray. -

Plan De Prévention Du Bruit Dans L'environnement (PPBE) Relatif Aux Routes Départementales D'eure-Et-Loir, Tel Que Prévu Par Le Décret N°2006-361 Du 24 Mars 2006

DIRECTION DE LA MAÎTRISE D’OUVRAGE Plan de prévention du bruit DANS L’ENVIRONNEMENT CONSEIL GÉNÉRAL D’EURE-ET-LOIR 1, place Châtelet - CS 70403 - 28008 CHARTRES cedex FAX : 02 37 20 10 90 - Tél. : 02 37 20 10 10 - www.eurelien.fr SOMMAIRE RESUME NON TECHNIQUE ............................................................................................................... 3 1. Présentation .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Contexte réglementaire .......................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Les Infrastructures concernées par le PPBE du Département d'Eure-et-Loir ........................ 5 1.3 Méthodologie mise en œuvre ................................................................................................. 6 2. Diagnostic ...................................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Synthèse des résultats de la cartographie ............................................................................. 7 2.2 Synthèse des résultats ......................................................................................................... 22 2.3 Actions réalisées au cours des dix dernières années ........................................................... 23 2.3.1 Sur la RD 828 ................................................................................................................ 23 -

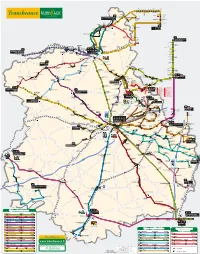

Transbeauce Final Version

VersaillesMairie Église Ruelles Arrêt desFerme Cars Mairie Mairie MongazonsCytises Fontenay Ormes Tilleuls Auchan FAVRIEUX LONGNES SOINDRES MAGNANVILLE MONDREVILLE Val St-Georges Église MANTES-LA-VILLE 28 LE MESNIL-SIMON Gare Quai 24 Pl. de l’Abreuvoir FLINS-NEUVE-ÉGLISE Gare Quai 10 LA CHAUSSÉE D’IVRY Mare à l’ogre DAMMARTIN- École EN-SERVE MANTES-LA-JOLIE Place de l’Europe D 928 Grande Rue Les Gâtines Calmette Rouges Centre TILLY Église Salle des OULINS RER - Gare Nord Fêtes Le Gleen La Cordelle POISSY ÉZY-SUR- 87 D143 Rte de Mantes EURE Bd. Gambetta Centre Cial R. d’Anet Mairie Longues Hautes Salle 88 SAUSSAY Perou des Fêtes Les Has Château AUFFREVILLE Tennis Les Marronniers ANET BERCHÈRES- POISSY CROTH R. des Tilleuls Lycée Abribus Sorel- SUR-VESGRE Peugeot Centre Moussel Centre Le Ranch Gendarmerie Écoles H. de Sorel 215 D MARCILLY-SUR-EURE SOREL- D 933 Église MOUSSEL Pont de Fer ST-LUBIN-DE Monument ROSAY 28 LA-HAYE 89 Rue de Herces Gare ST-QUENTIN-EN-Y. 88 SNCF Gare Routière 87 HOUDAN Trou du Berger République La Poste ST-GEORGES- Centre l’Étang Pont MOTEL ST-QUENTIN- ST-GERMAIN EN-YVELINES NONANCOURT SUR-AVRE Gradient 1 et 2 Pt. République Cocherelle FERMAINCOURT Marchezais- Hôtel de Bretagne MONTREUIL Route d’Anet Broué 60 Arpents Gare Routière Av. Hugo Centre Imp. de la VERT-EN- ACON Mairie Peluche Les Haut Vrissieul DROUAIS 1 6 8 Osmeaux N 12 6 le Rousset La Poste Mairie 88 Einstein Les Grandes L’Espérance 10 Arpents 25 26 28 88 Les Landes Vignes Longchamp Petit CHERISY TRAPPES VERNEUIL-SUR-AVRE Cherisy Marc Seguin Centre ST-LUBIN DES Chapeau DREUX Salle des Fêtes JONCHERETS des Roses ST-RÉMY- Le Luat Châtelet Les Cités TILLIÈRES- SUR-AVRE sur Vert Gare Routière SUR-AVRE Le Plessis Louveterie Oriels St-Rémy Les Bâtes S. -

Fiche Structure : Alliance Villes Emploi

Fiche structure : Alliance Villes Emploi - www.ville-emploi.asso.fr TERRITOIRE Pays : France Région : Centre-Val de Loire Département : (28) Eure-et-Loir Ville : Chartres Liste des communes couvertes : Amilly ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Bailleau-l'Évêque ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Barjouville ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Berchères-les-Pierres ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Berchères-Saint-Germain ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Bourdinière-Saint-Loup (La) ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Briconville ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Challet ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Champhol ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Chartres ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Cintray ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Clévilliers ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Coltainville ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Corancez ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Coudray (Le) ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Dammarie ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Fontenay-sur-Eure ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Fresnay-le-Comte ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Fresnay-le-Gilmert ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Gasville-Oisème ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Gellainville ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Houville-la-Branche ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Jouy ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Lèves ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Lucé ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Luisant ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Mainvilliers ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Meslay-le-Grenet ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Mignières ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Morancez ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Nogent-le-Phaye ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Nogent-sur-Eure ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Poisvilliers ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Prunay-le-Gillon ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Saint-Georges-sur-Eure ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Saint-Prest ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Sours ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Thivars ((28) Eure-et-Loir), Ver-lès-Chartres ((28) Eure-et-Loir) COORDONNEES Adresse : 13, -

Communautés De Communes Et D'agglomérations

Communautés de communes et d'agglomérations Gu ainville Gilles La Ch aussée-d 'Ivry Le Mesnil-Simo n ¯ Ou lin s Saint-Ouen-March efroy Anet Sau ssay Bonco urt Berchères-sur-Vesgre So rel-M oussel Rouvres Saint-Lub in -d e-la-Haye EURE Pays Houdanais Bû Abon dant (partie E&L) Havelu Serville Marchezais Go ussainville Montreuil Damp ierre-su r-Avre Saint-Lub in -d es-Jo ncherets Cherisy Saint-Rémy-su r-Avre Vert-en-Drouais Bro ué Dreux Pays de Bérou -la-Mulotière Germainville Lou villiers-en-Drou ais Sainte-Gemme-Moronval Boutigny-Pro uais Boissy-en-Drou ais VerneuMionltigny-sur-Avre Revercourt Prudemanche La Ch apelle-F orainvilliers Mézières-en-D rou ais Escorpain Allainville Verno uillet (partie E&L) Luray Ou erre Rueil-la-Gadelière Fessan villiers-Mattanvilliers Saint-Lub in -d e-Cravant Écluzelles Laons Garan cières-en-Drouais Garnay Les Pin th ières Charp ont Brezo lles Saint-Laurent-la-Gâtine Cro isilles Boissy-lès-Perche Châtain co urt Beauche Crécy-Cou vé Faverolles Rohaire Dreux Tréon Marville-Mo utiers-B rûlé Cru cey-Villages Villemeux-sur-Eu re Bréchamps Sau lnières Les Ch âtelets agglomération Saint-Ang e-et-Torçay Aunay-sou s-C récy La Ch apelle-F ortin Morvilliers Fon taine-les-Ribou ts Chaud on Coulombs Sen an tes Le Bo ullay-Mivoye La Man celière Lamb lo re Pu iseux Lormaye Saint-Lucien La Saucelle Maillebois Le Bo ullay-Thierry Le Bo ullay-les-Deux-Églises Orée du Nogen t-le-Roi Saint-Jean -de-Rebervilliers Lou villiers-lès-Perche Ormo y Perche La Puisaye Villiers-le-Mo rhier La Ferté-Vid ame Saint-Martin-de-Nigelles Saint-Sau -

Offer Véloscénie Self

Tour Code VS8C VÉLOSCÉNIE Highlights Mont St Michel, 3 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, Cathedral of Chartres Regional park Normandie- Maine VÉLOSCÉNIE - SPECTACULAR CYCLE ROUTE BETWEEN CHARTRES & MONT ST MICHEL SELF-GUIDED CYCLING TOUR Discover the Véloscénie, a long distance cycling route, from Chartres to the jaw-dropping Transfer to Saint-Malo Mont Saint Michel. Enjoy cycling through forests, pictoresque villages and the norman Mont-St-Michel Bagnoles countryside. Appreciate the calme and harmony of the spectacular nature while cycling del’Orne through this wonderful area of France. St-Hilaire- Condeau Chartres du-Harcou t ë Alençon DIFFICULTY KM LENGTH ARRIVAL Day 5 Alençon - Bagnoles-de-l’Orne Illiers-Combray 327 8 days mondays 53 km 7 nights 29.03. - 01.11.21 Today is a little more challenging but the scenery is ROUTE CHARACTERISTICS breath-taking and you will enjoy wonderful views throughout the day. Along the route, you can visit The main part of the tour takes place on plains, Day 1 Arrival in Chartres so it is flat. Some easy rises in the villages on the impressive small Château de Carrouges. The secondary roads gardens of the château could be a good option for a Day 2 Chartres - Illiers Combray 30 km picnic. Your day ends in Bagnoles de l'Ornes. This SERVICE INCLUDED Start the day with visiting the city of Chartres with city is full of charms, especially its Belle Epoque its sublime cathedral, a UNESCO world heritage neighbourhood. The city is also well known for its 7 nights in 3* / 4* hotels or chambres d’hôtes site and a masterpiece of gothic art. -

L'église De Saint-Loup

47 communes à la une Un peu d’Histoire … L’église de Saint-Loup L’église actuelle de Saint-Loup remplaça une chapelle des boiseries de qualité et des La Bourdinière-Saint-Loup fondée en 1270 (Cappella Sancti Lupi ou Saint-Loup statues dont une partie provient La Chapelle). En 1790, Saint-Loup devint pour un temps de l’église de Boisvillette Loup-en-Vallée. Dédiée à Saint-Gilles et Saint-Loup, supprimée le 27 janvier 1811 cette humble chapelle était fréquentée par de nombreux et réunie à celle de Saint-Loup. pèlerins. Elle fut, probablement, une annexe d’une En 1901, un « Sacré Cœur » 3 questions à Marc Lecoeur, Maire de La Bourdinière Saint-Loup. autre église située à 1 km, au lieu-dit, selon les textes, viendra compléter l’ensemble « Marché-Phaye ». Au XIXe siècle, des fouilles faites sur ainsi qu’une série de vitraux Votre Agglo : Comment présente- pédagogique fonctionne avec Damma- offerts par le Comte de Roussy riez-vous votre commune en quel- rie pour les enfants en primaire, et avec ce site confirmèrent la présence d’un édifice religieux. ques lignes ? Illiers-Combray pour les secondaires. Le Par ailleurs, des registres de sépultures indiquent que de Salle, alors propriétaire du « La Bourdinière Saint-Loup est située à collège Saint-Jacques de Compostelle à tel ou tel défunt a été inhumé « dans la nef principale ou château de Chenonville. Un 15 kilomètres au Sud de Chartres. Mignières est en charge du privé. » dans UNE des chapelles de l’église ». Le sanctuaire actuel reliquaire contenant un os de n’ayant qu’une chapelle dédiée à la Vierge, il s’agit donc St Loup est toujours l’objet de Elle est composée de deux bourgs : La V A : Quel est votre projet ou préoc- Bourdinière, traversée par la RN 10 à bien de l’église du « Marché-Phaye ». -

The Veloscenic Paris - Mont-Saint-Michel

THE VELOSCENIC PARIS - MONT-SAINT-MICHEL ILE-DE- La Seine FRANCE Caen Evreux Orne NORMANDIE Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris L’Eure Vire Château de Versailles PARIS The Mont-Saint-Michel and its Bay Station verte de Saint-Hilaire du Harcouët Versailles Vanves THE MONT- Avranches SAINT-MICHEL The Grand Domaine Bagnoles de l’Orne ETAPE 1 ETAPE 10 ETAPE 2 Flers Bagnoles- Château de Carrouges Massy-Palaiseau Sélune ETAPE 9 Rambouillet Couesnon de-l’Orne Pontorson Carrouges Mortagne- Château de Maintenon St-Hilaire- Manor of Courboyer Domfront au-Perche du-Harcouët Maintenon Epernon HAUTE VALLEE ETAPE 8 ETAPE 7 LE PERCHE DE CHEVREUSE Chartres ETAPE 3 NORMANDIE- Condé-sur- Alençon ETAPE 4 MAINE ETAPE 6 Huisne Illiers- Château de Domfront Mayenne Nogent- Combray Château de la Madeleine le-Rotrou Cathedral of Chartres Mayenne Alençon needle lace ETAPE 5 Le Loir CENTRE - VAL DE LOIRE Château de Nogent-le-Rotrou Sarthe 450 KM THE ROUTE 11 days / 10 nights From the Notre-Dame cathedral square in Paris to the Abbey of Mont Saint-Michel, the Veloscenic offers a journey through exceptional historical and natural heritage. This 450 km bike trip takes you on greenways and small shared routes and takes in a wide variety of landscapes. From valley forests and wooded rolling plains to the majestic bay of Mont Saint-Michel, the cycle route is punctuated by countless castles and historical monuments to visit, including five UNESCO world heritage sites. A mythical and inspiring holiday which is accessible for everyone! «ACCUEIL VÉLO» CYCLE HIRE INTRODUCTION AT THE DEPARTURE Loc Vélo - François Briane The national brand “Accueil Vélo” guarantees a quality Based in Normandy, this cycle hire shop offers bike welcome and service to cyclists. -

La Place Forte D'épernon

ÉPERNON À VOIR SUR VOTRE CHEMIN ACCÈS Vallée de l’Eure Épernon Chartres - Épernon par D 906 Installée à flanc du coteau qui surplombe la Drouette, place forte Gare SNCF - ligne Paris-Montparnasse - Chartres, gare à Épernon convoitée à l’époque médiévale en raison de sa position stratégique, la ville fut érigée en duché-pairie à la fin du XVIème siècle par le roi Henri III. De cette ancienne forteresse demeure le plateau de Diane, dominant la ville. Un monument y évoque les combats de 1870. HÉBERGEMENT/RESTAURATION L’église Saint-Pierre, d’origine romane, est la seule qui subsiste dans la commune. Très remaniée au XVIème siècle et endommagée en 1940, elle a été restaurée. Les seigneurs du lieu et leurs familles avaient Chambres d’hôtes et meublés dans les environs un caveau dans le chœur. S’y trouvent encore les restes en partie momi- Hôtels à Epernon et Hanches fiés de la fille d’un seigneur d’Épernon. Restaurants à Epernon et Hanches La place forte Le cellier des Pressoirs, vaste salle du XIIIème siècle à trois nefs Ravitaillement à Epernon et Hanches et sept travées voûtées, des piliers à chapiteaux sculptés et arceaux en ogive, fut le domaine des religieuses des Hautes Bruyères. Les vignerons d’Épernon étaient autrefois forts nombreux et les coteaux environnants étaient couverts de vignes. Selon l’usage féodal, chaque septième seau de vin revenait au seigneur en rétribution de l’usage du pressoir. Les chartes CHARTE DU RANDONNEUR du prieuré Saint-Thomas le désignent sous le nom de « cellier de Haute- bruyère ». -

60 Chartres Cathedral.Pdf

60 – Chartres Cathedral Chartres, France. Gothic Europe. Original construction c. 1145-1155 CE., reconstruction c 1194-1220 CE., Limestone, stained glass (6 images) One of the finest examples of French Gothic architecture The last of at least 5 which have occupied the site (war or fire destroyed earlier ones) Most of the original stained glass windows survive intact, only minor changes in architecture (since 1220 CE) Flying buttresses (which allowed the window size the increase significantly) Two contrasting spires: o 349 foot plain pyramid shape (1160 CE) o 377 foot Flamboyant (ornate decoration and tracery: intricate line pattern – also found in the magnificent windows) spire built on top of an older tower – taking 7 years to construct (early 1500 CE) – lightning destroyed the earlier tower destination for travelers (Christian pilgrims) o famous relics: the Sancta Camisa – said to be the tunic worn by the Virgin Mary at Christ’s birth . legend has it that it was given by Charlemagne (false) – it was gift by Charles the Bald – and it did not become an object for pilgrims until the 12th century o secular tourists – admiration for architecture and historical merit in medieval times: a focal point for the town, acted as a kind of marketplace on different sides of the building for different types of important goods built rather rapidly – giving it a cohesive design still in use Statistics: • Length: 130 metres (430 ft) • Width: 32 metres (105 ft) / 46 metres (151 ft) • Nave: height 37 metres (121 ft); width 16.4 metres (54 ft) • -

The Chartres Cathedral Labyrinth, Faqs by Jeff Saward

The Chartres Cathedral Labyrinth FAQ’s Jeff Saward As one of the best-known examples in the world, much has been written and said about the pavement labyrinth in Chartres Cathedral. But what is fact and what fiction? Here are some of the most frequently asked questions about this labyrinth... The Chartres Cathedral Labyrinth – photo: Jeff Saward/Labyrinthos Introduction It is no wonder that Chartres Cathedral has drawn so much attention over the course of its long history. As a repository of holy relics, the cathedral has attracted pilgrims for over 1000 years, and in much the same way has attracted popular folklore as well as misinformation. For instance, the story that the cathedral is situated on the site of a former Druidic temple, erected in honour of the “Virgo Paritura” (The Virgin who will conceive) is not based on any historical or archaeological evidence. As Mgr. Michon has shown (Michon, 1984), this story was created in the 16th century and popularised in the early 17th century by Sebastian Rouillard. Recent archaeological excavation has shown that the cathedral overlies the alignment and foundations of earlier Roman buildings. However, the topic of this study will be one particular part of this remarkable building, the pavement labyrinth situated in the nave of the cathedral. Not surprisingly, the published information about this labyrinth is riddled with confusion, supposition and fantasy, probably more so than any other labyrinth. Labyrinthos Archive 1 When can you walk the labyrinth at Chartres? Chartres Cathedral is a working building and a place of worship. Normally, the nave of the cathedral is lined with chairs and most of the labyrinth is subsequently obscured.